Reviewed by Ian Carter

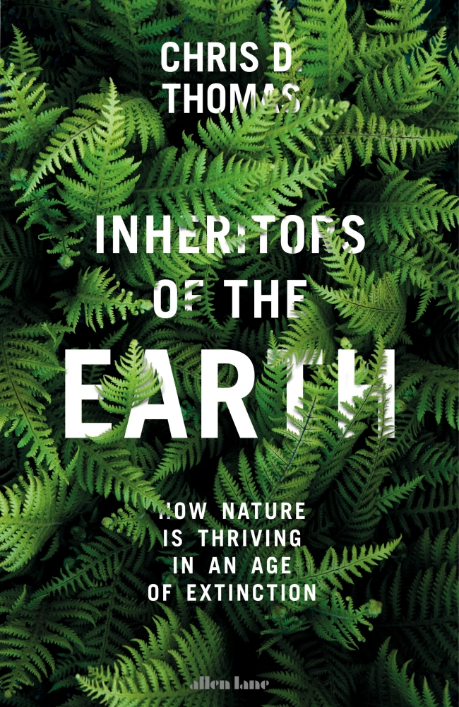

The full title of this book tells you most of what you need to know about its main message. While conceding the point that there have been significant losses of wildlife, the book focusses on the positive aspects of a human-dominated world.

It is one of a growing number of recent books that take an upbeat view of human-induced changes to the natural world and it is worth reading even if you think you are unlikely to agree with it. These arguments are going to be heard increasingly in the future; at times (as here) voiced by someone who is genuine about the message, and at times by those with a vested interest in playing down the adverse impacts of humanity.

He makes the point that in most country-sized areas of the world humans have increased biodiversity. Take Britain, for example. Before we started to affect change, much of the landscape would have been forest. It would have supported a rather limited assemblage of wildlife, constrained by the habitats available. We have lost the top predators that were once present but now we have a diversity of grasslands, heathland, arable crops, coppice, artificial wetlands and urban areas. These habitats all support a different assemblage of species, some of which moved in naturally and others that have been introduced by humans. This is part of his positive message and it also raises interesting questions about just how far back we should look when trying to set our conservation baselines.

From this starting point the book moves onto a more global overview and he uses two key arguments to underpin his optimistic assessment of the overall state of nature.

Firstly, he suggests that humans must be included in the definition of ‘natural’. His point is that humans evolved naturally just like all other species and so all human-mediated change is ‘natural’. This is undeniably true, but is it helpful? People using the term ‘natural’ to mean wildlife other than humans are not deniers of human evolution – they are simply using it as shorthand to mean ‘other wildlife’. The implied separation between humanity and the rest of the natural world is deliberate and, I would argue, useful. Yes, if you chop down a woodland and replace it with a supermarket, technically, it is still ‘natural’. And if you distribute rats and other mammalian predators around the world’s islands resulting in the extinction of hundreds of flightless bird species and threatening breeding seabird populations, that is natural too. But that doesn’t make it a good thing and I don’t agree that it is a helpful way to think about our impacts.

Another recurring theme is the referencing of events on earth over vast timescales in order to provide reassurance that all will be well in the longer term. There have been previous catastrophes and mass extinctions and yet life on earth has responded, resulting in what we have now. He sees the current all-pervasive impacts of humans in a similar light. We are changing things on a massive scale, altering habitats, modifying the climate and shipping species all around the planet. This, he suggests, should not necessarily be regarded as a bad thing. Change is inevitable. It has happened before and wildlife will adapt and thrive. There will be losses but there will be also be gains and we should all relax a bit more about the longer-term outcomes. Although he makes a strong case, you end up reflecting on what timescale is the most helpful when thinking about wildlife and conservation. If you are kept awake by what has happened in the last few, short decades and what might happen in the next few decades then his arguments may not provide you with much comfort.

The book is very well-argued and thought-provoking throughout. He uses examples from around the world to add texture so you will learn a lot from it even if you don’t agree with him. I wasn’t won over by his overall conclusions but that’s not to say the book hasn’t influenced me. It has helped reaffirm my view that ‘naturalness’ (using the definition that excludes humans) is a greatly undervalued concept in nature conservation. Nothing is entirely natural anymore because humans have influenced everything to some extent. But we can still aspire to setting aside areas where human impacts are minimised as far as is possible and surely that is a good thing. I did find parts of the book more reassuring and it has perhaps nudged my views of non-native species just a little in the direction of greater tolerance – in part because we don’t really have any other option.

This book reinforces the point that the way we perceive the natural world owes much to our individual responses and philosophies. Parakeets and Grey Squirrels either brighten up your day and offer hope for the future or provide a stark reminder of the damage we have done – or perhaps a bit of both depending on mood. Whatever your reaction to them, this is a book that is well worth reading.

Inheritors of the Earth: How nature is thriving in an age of extinction, by Chris D. Thomas is published by Allen Lane.

Remarkable Birds by Mark Avery is published by Thames and Hudson – for reviews see here.

Inglorious: conflict in the uplands by Mark Avery is published by Bloomsbury – for reviews see here.

[registration_form]

Interesting…

For me, I consider anything that is deemed natural needs natural control loops present in the environment. For everything we consider natural, there are regulating and limiting factors. Arguing that humans are part of the natural system is very valid, but to my mind that is in a hunter-gatherer role. We should be one of those top predators. In short, we’ve stopped filling our niche. We are no longer regulated or constrained by our environment (though I believe that will begin to shift soon as the population continues to rise).

I’m also not sure I fully subscribe to the ‘Britain used to be fully forested’ approach. We have too many specialist species for other habitats. That’s not to say that, for example, heathland existed over large areas, or that I fully agree with Vera’s ‘park like landscape’, but I do think those areas must have existed, possibly as ephemeral habitats, that would have been created by some mechanism we may, as yet, have failed to model. Merely trotting out the wildwood hypothesis doesn’t satisfactorily answer the biodiversity question for me.

Thanks for the review. It may be good to read some upbeat thinking amongst the horror!

If Britain was ever fully forested it would never have held animals the size of mammoths or dinosaurs or any large grazers at all. What does this author say about the Pliocene? Does he think Britain was fully forested at the end of the Younger Dryas? Is he just cherry-picking his datum line to support an argument that human de-forestation is a good thing, and even eradicating some ancient woodland for HS2 should not be resisted by conservationists because ‘nature’ will somehow thrive despite the loss?

Of course EVERYTHING is natural, even asteroid strikes, war and smallpox, it is simply a fact that some things ‘we’ do have adverse effects upon the environment which ‘some’ of us choose to protect because we want to. I am in favour of eradicating smallpox, exterminating a part of nature, but both the US and Russia have resisted the destruction of remaining virus stocks.

It is not wrong to pick and choose what we want to preserve. It is always a choice.

It sounds like Chris Thomas is some kind of happy, clappy, absolutist, but I am in favour of restraining what we do. I could be talking bollux, because I haven’t read his book, but…

…after all, given no restraint, natural events may well mean that Mr Thomas’s off-spring, along with those of most others, do not survive… Does he not consider that?

It would still be natural. Life would continue. Evolution would not stop. Just without (almost all of) us.

Thanks Mark, I might add this one to my reading list. If you haven’t already read it, I would definitely recommend “The New Wild” by Fred Pearce, which also challenges many long held views on non-native species and their role in ecosystems.

Maria – thank you. I heard Fred (whom I rate) talkin about his book on Springwatch Unsprung (I think) – and it didn’t grab me.

Fred Pearce’s book shares many similarities with this one. Essentially, if you can relax enough to see changes wrought by humans as ‘natural’ there is plenty of scope for optimism. If you hanker for wildlife habitats that remain relatively free of human interference and intrusion then the world is an increasingly gloomy place. On a scale of 1 to 10 I was probably a 9 in valuing human-interference-free habitats above everything else and having read these books I’m maybe now an 8. An interesting category of wildlife site sits between these two extremes – sites constructed by humans but managed entirely for the benefit of wildlife (and the people who come to see it). Look at the Avalon marshes in Somerset with Google Earth. It has been sculpted by humans to provide optimum conditions for reedbed birds, especially Bitterns. It has been staggeringly successful, yet there is an undeniably artificial and unnatural feel to it.

I certainly agree with you with regards to valuing human-interference-free habitats. The only interesting point from Fred Pearce’s book is regards to our tolerance of non-native species – I often encounter the view that all non-native species are bad and should be removed at all costs, and I sometimes wonder if this is entirely necessary, or a good use of resources, in all cases (many cases yes, but probably not all).

Whilst I don’t see that the changes wrought by humans as being “natural”, you raise the interesting point that a lot of our wildllife sites are actively managed (and a lot of species benefit from this). I suppose there is a line (albeit maybe a slightly fuzzy one at times) between human management and human interference – a bit of grazing to encourage some rare species can be put on the side of human management, but littering our coastal/marine habitats with rubbish can certainly be put on the side of human interference!

I don’t think many people argue for the complete removal of Little Owls or stinging nettles. I believe the motivation is simply whether an introduced species is causing significant harm to our ecosystem, and then whether it is possible to remove it.

Choices.

Thanks for the review. No doubt the book will be widely used by apologist for ‘just one more road/car park/supermarket’. Right with you on the use of the word ‘natural’. And it’s undeniable that humans have massively decreased the biodiversity and bio-abundance of the world. We may have increased diversity in small areas, but overall we have caused massive extinctions, and the point that they may re-evolve in a few hundred million years is no comfort to most of us. Was it an East European ecologist who said that to cause the extinction of a living creature is a great sin.

The resetting the clock argument about mass extinctions – they’ll allow a different set of species to evolve eventually and change the direction of evolution – is a very, very weak one to me. The world is always changing and its species with it, the idea that things are stagnating without mass extinctions is a bit off. Paleontologists are now realizing that mammals were already diversifying before the dinosaurs parked their clogs – there was at least one badger sized one. The image of mammals as a few tiny shrew like animals skulking in the dark away from the ferocious dinosaurs and their subsequent ascendancy is a nice story, but is now seriously looking like a load of crap. It turns out that there was at least one giant flightless bird – analogous to an ostrich – that existed alongside the dinos. Mammal diversity was drastically reduced by the same ‘event’ that killed them off. It took millions of years for it to get back to what it was, just with a different set of players – how is that better?

The ‘extinction is natural and we are part of nature’ arguments are being used by those defending crass exploitation of natural resources and loss of wildlife, the fact that this also undermining the same ecological functions that we need (such as soil creation and conservation) is conveniently lost on them. There are plenty involved in driven grouse shooting including the small rag tag bunch of DGS friendly ‘conservationists’ that use the same arguments to push for status quo in the uplands arguing against reintroductions and ecological restoration – ‘we’ve been doing this for so long we need to keep doing it’. I’m afraid I don’t believe that the world, especially us, has gained anything by the extinction of the Hawaiian mole duck, Madagascan aardvark, Steller’s sea cow, sloth lemur, adzebill, passenger pigeon or great auk well before their time or more appropriately before their chance to evolve into new species. Trying to visualize them and the way they interacted with their ecosystem or how eventually other wildlife might evolve to fill their niches (IF that could happen on a human dominated world) is a very, very poor substitute for the real thing. If people are a product of nature and therefore everything we do is natural what does that say about Auschwitz exactly? I saw this book in my library some time ago and when I read the blurb and dipped into the pages my heart sank – is this someone trying to dress up a terrible reality as something that’s actually wonderful – an act of desperation, an intellectual prozac?

Sounds like he needs to take a long hard think about this quote from the plaque above Gerald Durrell’s ashes at Jersey Zoo (see wiki):

The beauty and genius of a work of art may be re-conceived, though its first material expression be destroyed; a vanished harmony may yet again inspire the composer; but when the last individual of a race of living beings breathes no more, another heaven and another earth must pass before such a one can be again.

And his use of the word ‘natural’ just ends up being another way of saying ‘everything’, which pointless.

That’s a good way of looking at it. If ‘natural’ is redefined to refer to ‘everything’ then it becomes meaningless. In similar vein the book’s use of vast timescales are close to meaningless in relation to decisions about human activities now or in the coming decades. Take a long enough timescale and the Earth ceases to exist so why bother with anything.

I haven’t read the book, but this review puts me very much in mind of both Fred Pearce’s book, and of Emma Marris’ 2013 “Rambunctious Gardener”. Both are serious contributions to the literature, and seriously considered (for exemple, Marris is on the preparatory reading list for Oxford Uni’s Masters’ course in Biodiversity and Conservation Management). Whilst I like the iconoclasm of this way of thinking, it does concern me that both Pearce and Marris seem to allow the rhetoric of their argument to carry them into territory that makes them welcome allies for those who wish to “greenwash” the most destructive of human activities.

For example, Marris extols the wonders of watching migrating Sandhill Cranes on the Platte River. As she points out, this spectacle is largely the result of deliberate action by humans, and deliberate dredging of the river to maintain the local habitat. What Marris fails to point out is that it is human activity that has made this necessary, as we have developed most of the surrounding area so that it is inhospitable for the Cranes. The Crane population is now extremely vulnerable, and that rather than being a self-sustaining, functional feature of the ecosystem, just a small change in policy or chance accident – a shift in climate, a succession of poor winters – could obliterate this corner of her “garden” forever.

I’m afraid I’m not even faintly impressed by this argument. For starters, from what Ian says it has got the forest bit wrong – yes, Britain would have looked very different, with very different habitats but the ‘limited’ species is just plain wrong – even before you factor min Franz Vera’s theories which suggest large herbivores could well have been present – and what we know from the very few ‘near natural’ forests in Europe, which behave in a very different way from the stood over coppice natural/neglected wood, depending on your viewpoint, we are familiar with in England today.

Beyond that, what really needs questioning is the unecessary impact of extreme capitalist thinking – a huge proportion of the losses in the English countryside have come from the last 2-3% of ‘squeeze’ from intensive farming – an approach which, having finished off the wildlife, is starting to eat itself with soil erosion, loss of pollinators etc. I flew over the Avalon Marshes yesterday. Ham Wall and Shapwick are tiny even in the Somerset Levels landscape. 500,000 hectares of similar habitat in lowland England would have a negligible effect on farming output, yet a spectacular impact on biodiversity – yet we get conservationists questioning the 2,000 hectares of the Knepp rewilding. If we believe our own rhetoric we should be arguing for the Natural capital committees proposal to create 250,000 hectares of ‘community forest’ around our towns and cities – yet I am still looking for a single reference in the conservation communications I look at.

Roderick – the line about forests and limited species is my summery and, admittedly, a simplification of the reality. The book is actually very rigorously argued and backed up by detailed references. The basic point is still valid. As an ornithologist I’d be confident that we have many more breeding species now than we did 7-8,000 years ago. If you look at total bird/wildlife biomass then it may be a different story, though with 50 million pheasants and birds exploiting arable crops extensively it would be interesting to know how the comparison would work out.

It may be possible to demonstrate that at some geographical scales in some places human activity has increased biodiversity but overall our global impact on biodiversity is clearly extremely negative. The rate of species extinctions is by all credible estimations vastly greater than during pre ‘Anthropocene’ times and no-one is suggesting that there is a level of speciation going on that comes within a million miles of balancing these losses let alone outweighing them. So any positive effect on biodiversity we have had has been extremely local and far outweighed by the losses elsewhere.

The question is what do we do about this? I believe we should fight strongly to protect whatever remains of the natural and the pristine and to minimize further losses of biodiversity. However, we also must recognize that the 7 billion of us are not just going to disappear and that, whatever we may wish, there will continue to be towns and supermarkets and railways and all the rest built and so we also need to try to find ways of achieving this without eliminating nature (in the sense advocated by Ian rather than that suggested by Chris Thomas) entirely. As others commenting on this thread, I have not read the book but I would suggest (without necessarily embracing his apparent optimism) that Thomas’ arguments possibly have some value in relation to how we address this question.

When building the infrastructure needed by human populations (we may not need a high speed rail link from London to Birmingham but it is hard to argue that people don’t need homes, shops, hospitals, waste disposal sites, etc) we should certainly endeavor to avoid destroying woodlands, wetlands and other habitats but should we not also be looking to how we can create new habitats? If we wish, urban developments can include green roofs and walls, ‘open mosaic habitats’, SUDS schemes, woodland and wetland and potentially these can range from pocket handkerchief-sized pieces of habitat to really large scale projects. This is not and should not be an alternative to protecting important existing natural and semi-natural sites and habitats or or re-wilding land where opportunities exist but can offer an additional strategy and a way of ameliorating the impact of the urbanisation that is going to happen anyway. Some of these things happen already on a small scale but why not demand that all planning consents should routinely require that they are a major feature of every new development?

You’re right! There’s massive potential for creating wildlife habitat on what truly is non productive land in any sense – the collectively vast area of close mown grass that is kept that way…merely for the sake of it. You mentioned SUDS, we have an excellent one a few miles away that really was developed as a wildlife habitat, there’s another a bit closer that looks pretty good, but I must have seen another 12 here and there that are only the bog standard hole with water surrounded by two inch high grass. Look hellish and near zero wildlife value. It’s depressing how little progress has been made in urban conservation decades after it became a higher profile issue – definitely loads of rhetoric, not matched by action. The conservation movement needs to be ballsier about this. The local SWT branch has on several occasions asked the council if it could have more areas of long grass in our parks – they were turned down flat on the basis some people would complain. We all pay council tax, but people who don’t like short grass are expected to put up with it, but can’t have what they want. Basically this is undemocratic, we need to point this out.

Les highlights areas where tidiness overrides wildlife enhancement, particularly regarding rough grasslands. This habitat is one of the most undervalued by many, even nature conservation wardens and managers. Often it seems grassland has to be managed in some way to be of value eg. cut or mown to be of value to wildlife. Few seem to realise that rough grassland develops its own structure and species complement, often of species that cannot survive in a short sward. Examples would be numerous invertebrates including important soil-forming detritovors, spiders, orthoptera, many reptiles and amphibians and a key species within the predator food chain; the field vole. High field vole numbers are key to sustaining barn owl and short-eared owls as well as kestrels etc..

I have had some significant success locally with the Thames Chase Community forest (who create manage hundreds of acres of forest and grasslands) changing their broad annual mowing regime to a more sensitive and varied operation, leaving significant areas of rough grassland that now team with wildlife. Also, the Local Council leave margins and areas within parks and open spaces un-mown and with lots of hedge planting, which is great, though ‘mistakes’ are sometimes made and anthills and swards get battered by toppers. Making good contacts and highlighting areas where action is possible can reap rewards, don’t give up.