This is essentially an alphabetical list of species names and a few other rural terms.

What’s in a name? If I told you that I get Apple Birds, Aizacks, Woofells and Wrannocks in my garden, as well as Spadgers and Jacobs would you still be with me? Well, I do.

These old, largely unused, mostly regional names (all the above are birds) are of interest and it’s good to see this collection of them gathered together. Should we reinstate them? There aren’t many candidates for rescue in here that I can see although I think that calling Snow Buntings Snowflakes in this day and age would be quite fun.

If the variety of names illustrates the former diversity of our language does their demise mean that it now the poorer? Well, that’s a reason for having them in books like this one (a kind of word museum). But I doubt that a single reader of this blog (whilst I admire all of you for your breadth of knowledge) knew that the birds’ names above were of Chaffinch, Dunnock, Blackbird and Wren, as well as House Sparrows and Starlings. We need a common language to share our thoughts and in these days we speak to people by various means across the globe, not just in the street where we live or in the big town on market day. So I guess I find the names interesting – some are fascinating – but I’m not going to mourn their loss.

I was reminded of this quote from Richard Feynman;

You can know the name of that bird in all the languages of the world, but when you’re finished, you’ll know absolutely nothing whatever about the bird. You’ll only know about humans in different places, and what they call the bird. So let’s look at the bird and see what it’s doing—that’s what counts.” (I learned very early the difference between knowing the name of something and knowing something.)

https://www.goodreads.com/quotes/103022-you-can-know-the-name-of-a-bird-in-all

There’s a lot in what Feynman was told by his father but it is also true that many of these names are more descriptive of the species, its behaviour or its habitat, than current names. ‘Queen of all Poisons’ tells me more about Aconite than does the name Aconite!

I enjoyed flicking through this book but for a 208 page illustrated paperback, which is essentially a list of names, it is quite pricey in my view.

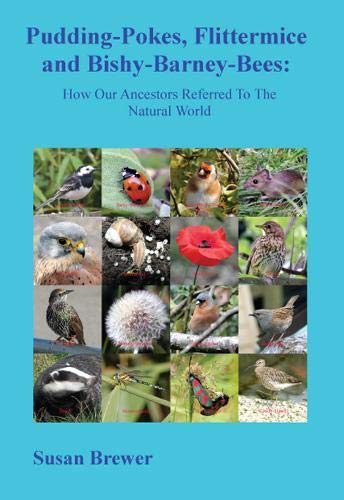

Pudding-Pokes, Flittermice and Bishy-Barney-Bees: how our ancestors referred to the natural world by Susan Brewer is published by Virtual Valley. Virtual Valley has published mostly books by this author but for what appears to be a self-published work the design and production values are good. Available from major booksellers including , I must say, Amazon.

Remarkable Birds by Mark Avery is published by Thames and Hudson – for reviews see here.

[registration_form]

Feynman is right that there is a difference between knowing the name of something and knowing something but being able to name things is a crucial first step to knowing them more fully. If we perceive all birds (or butterflies or bees or any other group of organisms) as an indistinguishable mass we can never hope to know anything meaningful about them and we are unlikely to care much about what happens to them. If birds are just birds then the disappearance of turtle doves from our countryside won’t seem to matter much if Trafalgar Square is still full of pigeons. Once we start to perceive them as different species we can begin to understand the different lives they live and the different problems they face and to care when some species decline towards extinction. If we are lucky we may know enough about them to be able to provide effective conservation responses to their problems.

Mary Colwell’s natural history gcse is therefore an important effort to instil a wider appreciation and knowledge of the species that share our environment with us. The worry is that this course will be an optional subject that will be chosen by a minority of students who are already engaged with nature. It would be marvellous if we could also see natural history becoming a more significant part of the compulsory curriculum for children in the earlier stages of education.