If you live in Lincolnshire you will want to own this book and it will be an invaluable reference source for your everyday birding for years to come. This volume follows a 1989 predecessor, and much has changed and occurred in the last 30+ years.

It appears that this book was conceived as a way of doing something useful during lockdown and the fact that it is now available, and of high quality, is quite remarkable given that timescale. Even a certain Bearded Vulture, present in Lincolnshire as late as October 2020, appears, with text and photographs, in these pages.

To some extent this book follows a fairly normal and logical format in its 230 pages. The last 40-odd pages have an index, a checklist, references, acknowledgements and in this case a 30-page gallery of excellent photographs of birds (some rare, some common). The first 25 pages set the scene about the genesis of the book, the important birding sites in the county, previous avifaunas, the growth in records – all the slightly dull stuff which is actually important and to which you will have to refer often if you use this book regularly so it must be there. And that leaves 160 pages for a systematic list of species.

Anyone considering producing a county avifauna (and my adopted county of Northamptonshire needs one (but no, not me)) might be drawn in either of two main directions. Does one give prominence to the rare birds of the recent decades (rare breeders and vagrants) as the stars or does one document the broader scale changes in time, such as declines in once-common birds such as those found on farmland. Let me say that I think the authors have navigated that issue pretty well in these pages. But it is the perennial issue for any news editor; few stories are important and interesting, and if only one, then the interesting tend to win over the important. And its worse for the authors of an avifauna which is expected to say something about every species because, for some, there may be nothing important or interesting to say!

As one works through the systematic list one encounters species such as Yellow-nosed Albatross (a single record photographed very well by a fisherman at a lake and seen on one day and by no birdwatcher), Golden Eagle (5 records, last seen 1928) and Blyth’s Reed Warbler (four records (one pending acceptance by British Birds Rarity Committee) all since the previous avifauna). Rare birds such as these are listed by locality and have a county map with dots showing their locations. Common species often have their Breeding Bird Survey graphs with Lincolnshire trends compared with east of England and England – this is a good idea.

I think the authors have been over generous with photographs of birds. Over generous? How can that be? Well, I don’t need three images of male Blackcaps to read about Blackcap trends in Lincolnshire, nor do I need much of a reminder of what a Blackbird is. Do I need a headshot of a Golden Eagle to read about those five ancient records? Even the Yellow-nosed Albatross has three images of the same bird looking…errr…the same in all three (the middle one is best as it shows a Mute Swan in the background). Given that there is a gallery of images later in the book – and this is very pleasing on the eye – I’d have considered cutting a whole bunch of images.

I’d also have considered cutting out some of the maps showing the sightings of rare species – they don’t add much really because there are an awful lot of dots on a few well-watched coastal sites and in any case the locations are tabulated or mentioned in the text. They take up space which could have been better used in my opinion.

The species texts are very good. Many of them were individually delightful reads and taken together make this a really good book. I am, I must confess, a words man. Only where a map, graph or table really does do the job better (as they often can) should they be allowed to cramp the style of someone who has something to say in the written word. And in this case those written words could usefully have been longer accounts in some places and in larger font in all cases. A slight step up in font size would have made the book look more inviting.

There are some very good photographs in this book but some of them get a bit lost. Some of the images of sites and habitats are wonderful and should have been given more prominence, for example Early morning at Kirkby Moor LWT (p49), A rough day at Pyewipe, Grimsby (p94), Lincolnshire wolds (p131) and others and maybe they should have had a bit of the photo gallery to themselves.

Lincolnshire to the east of the A1 is off the beaten track – you don’t go through Lincolnshire to get anywhere else (except to the Humber Bridge) – and I was amused to read that Henry VIII described it as our ‘most brute and beastly shire‘ which seems unduly harsh these days. I’ve had some good days in this county and most of them have been birding. It’s a great county for birds, both now and in the past, and this book shows that it also has a thriving and dynamic birding community.

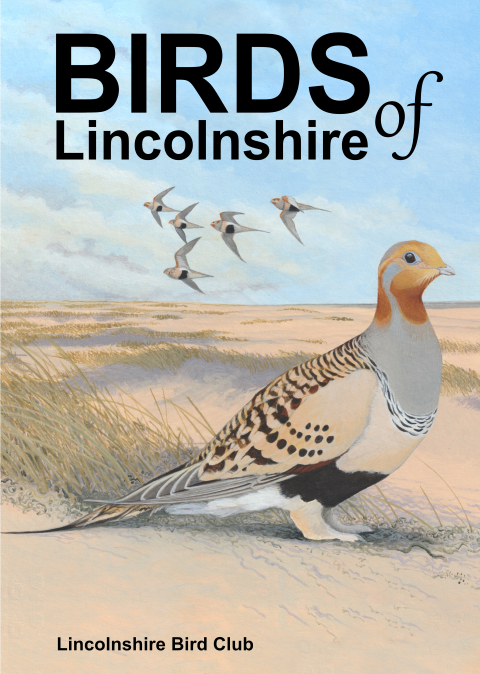

It is endearingly eccentric to have a species not seen in the county in the twentieth century, and not expected to reappear in the twentyfirst, as the cover illustration. Well done! I enjoyed reading of the flocks of Pallas’s Sandgrouse that flew through Lincolnshire in the late nineteenth century invasions and that type of recollection is entirely appropriate in a county avifauna. The cover illustration was painted by Nic Borrow and it is charming and striking. The four authors, the county and its birders ought to be rewarded by a Lincolnshire-only sandgrouse invasion this October – it would be a just reward for producing such a good book with this choice of pin-up bird for its cover.

Birds of Lincolnshire is published by Lincolnshire Bird Club tomorrow, 15 March. If you are a member of the Lincs Bird Club you should snap up the pre-publication offer today if you possibly can!

[registration_form]

Thanks for a most enjoyable and fairly balanced review of our book Mark. In my opinion you’ve given the prospective reader a really good insight into what they will find when they open the cover.

I am sure all keen birders will agree with the sentiment expressed in your penultimate paragraph, I certainly do!

Phil – you’re welcome. Congratulations to the team that produced such an excellent book, so quickly and so well. It is a major achievement of which you all should be proud.

I’d suggest Lincs goes one better and creates the habitat for its Sand Grouse – and I know just the place – Laughton between Gainsborough and Scunthorpe, next to the river Trent. Part is forest and part poor agriculture, all on an sand just waiting to be converted to Sand Grouse dunes !

A few birds out of the great 19c flocks actually laid eggs in Nottinghamshire, so it’s worth a go.