I haven’t seen as many Wrynecks as I wish I had and most of my sightings have been in southern Europe where they are much commoner than here, but even so they are quite difficult to encounter. My first UK record was on the beach at Minsmere in the early 1970s and as a schoolboy I was thrilled to have found this migrant bird feeding on the short grass of the coastal dunes. Most of my other UK records are also from the east coast in early autumn but I get the impression their numbers have declined. This would make sense as I learn from this book that Wrynecks have declined greatly in many European countries including in Scandinavia from which our passage birds must come.

A century or so ago, Wrynecks were common and widespread breeders in England, but had already been lost from Wales. They declined from north to south and the last English breeding record was from Buckinghamshire in 1985. There was a spasm of Scottish breeding records in the 1960s up until 2002 but now the Wryneck appears to be gone from the UK as a breeding bird. The once-common Wryneck ‘did a Turtle Dove’ five decades or so before the once-common Turtle Dove was noticed to be falling precipitately in numbers.

In my adopted county of Northamptonshire, the poet John Clare knew much about this bird, quite a feat I’d say without binoculars or mist nets being at his disposal. I was pleased to see a passage from Clare’s poem The Wryneck’s Nest in these pages which made it abundantly clear that Clare knew this bird well, and far better than I do.

These slightly odd-looking birds are woodpeckers and also trans-Saharan migrants and this is a book to introduce you to them in an engaging manner. We learn much about their biology and status, and some of it surprised me. I wouldn’t have thought that Wrynecks would have as large a clutch size nor that they would occur in the range of habitats they favour on migration. But then, what would I know? I’ve hardly seen these birds. I enjoyed, and benefitted greatly, from this compilation of information.

For a fairly small and well-camouflaged bird, Wrynecks have a strong showing in myth and folklore. Their loud song, and the fact that they are migrants, meant that their annual return was noticed and associated with the end of winter and the coming of better weather, but (as with Green Woodpeckers) their vocalisations were also thought to precede rain. I was fascinated to learn of the Wryneck wheels in Ancient Greece and that Wrynecks are so strongly associated with eroticism and passion. I’ll be looking out for people wearing lapis lazuli rings engraved with images of Aphrodite so that I can ask whether the ring contains the eye of a Wryneck by any chance (and whether it is the right or left eye).

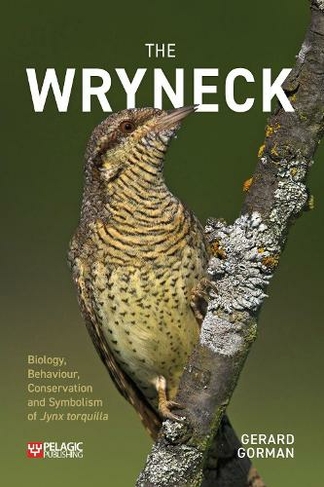

The cover? It’s an entirely appropriate and impressive image but I feel that the placing of the title detracts from it a little. I’d have made the bird smaller (I reckon it is larger than life-size here) and dropped it down the cover a bit to leave space between the bird’s head and the title, but even so, I’d give it 7/10.

The Wryneck is a head-turner of a bird. It gets its name from its habit of twisting its head from side to side when threatened or handled (perhaps to mimic a snake) and it’s a bird that any birder would want to see if one is in the vicinity. This book is well worth a close look too.

The Wryneck: biology, behaviour, conservation and symbolism of Jynx torquilla by Gerard Gorman is published by Pelagic Publishing.

[registration_form]

Thank you, Mark, your review has stimulated me to buy this book. I’ve never been fortunate enough to find this bird but have always been fascinated even by what little I know about it.

“…the fact that they are migrants, meant that their annual return was noticed and associated with the end of winter and the coming of better weather,…”

Various old provincial names for the wryneck reflect this including ‘Cuckoo’s mate’ (and variants thereof), ‘Barley bird’ (from its appearance at the time when barley was traditionally sown) and ‘Mackerel bird’ (coincidence of its arrival in Guernsey with the mackerel season).

Recently reading some old (1972) copies of John Gooders “World of Birds” that i had been given.

I was surprised to learn how aggresive Wrynecks can be when searching for nest sites, destroying eggs, chicks, and pulling out the nests of tits and other hole nesters in their territory, then often, after a wave of destruction, choosing an unused hole after all.

Residents of Oxshot, Surrey, complained of those “nasty wrynecks”, due to attacks on their garden nestboxes.

Those were the days.

Trapit – very interesting.