Nick MacKinnon is a freelance teacher of Maths, English and Medieval History, and lives above Haworth, in the last inhabited house before Top Withens = Wuthering Heights. In 1992 he founded the successful Campaign to Save Radio 4 Long Wave while in plaster following a rock-climbing accident on Skye. His poem ‘The metric system’ won the 2013 Forward Prize. His topical verse and satire appears in the Spectator, and his puzzles and problems in the Sunday Times and American Mathematical Monthly. Email: [email protected]

Turbine 44: Withins Height SD 97736 35051 ///sobs.suffer.panoramic

8 July 2024 The revised planning policy for on-shore wind was announced this morning. The new lapwings and curlews have almost fledged, and all I can do to manage overwhelming anxiety about these new birds is to walk up to a turbine site.

To be clear, I voted Labour in Keighley, with my intention splashed on the front page of the Sunday Mirror. The circumstances that put me in that exposed position vis-à-vis the secret ballot are too complicated to unravel here, but the journalist drove from South Shields to doorstep us in Bannister Country, and then summoned the photographer from Leeds. Until I bought the paper in Haworth Co-op, I thought it might be a tabloid sting set up by Muttley.

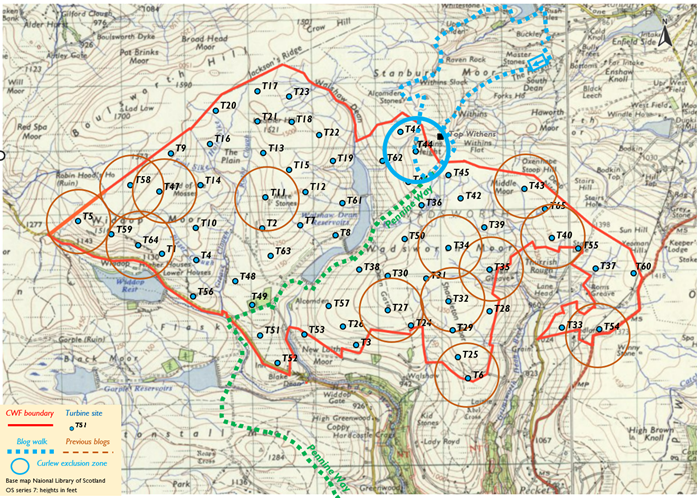

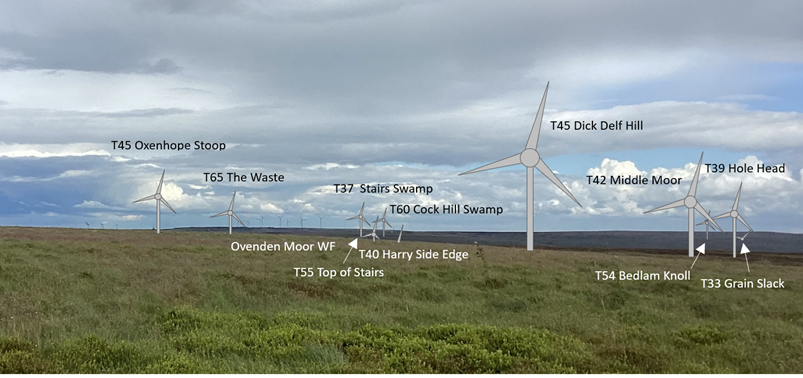

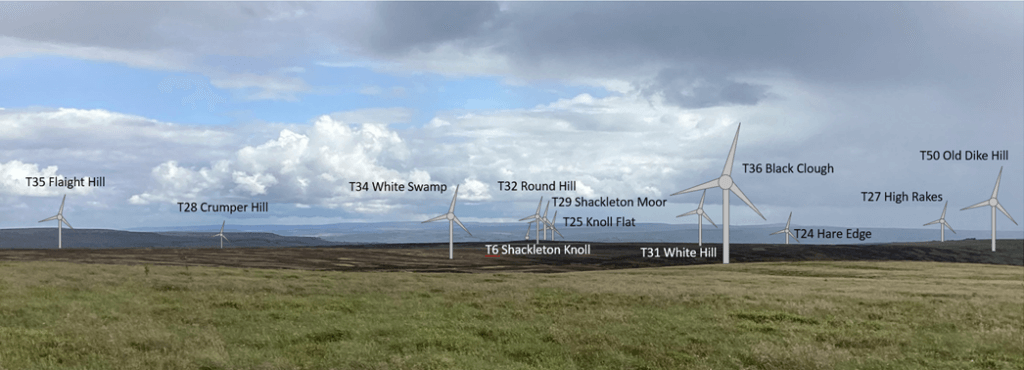

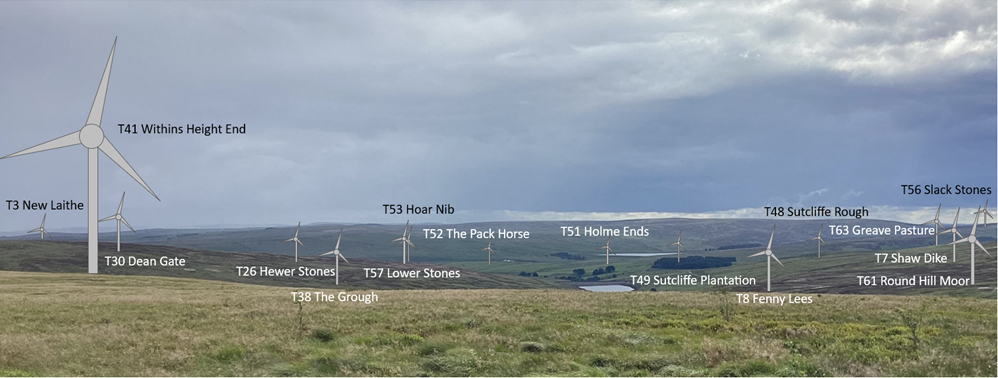

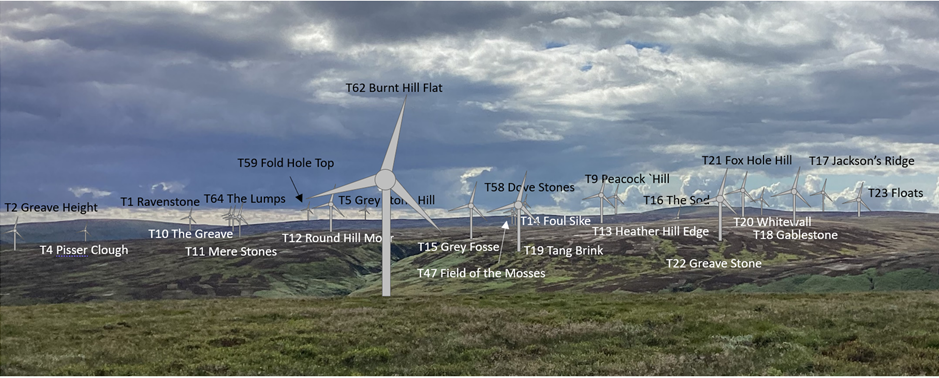

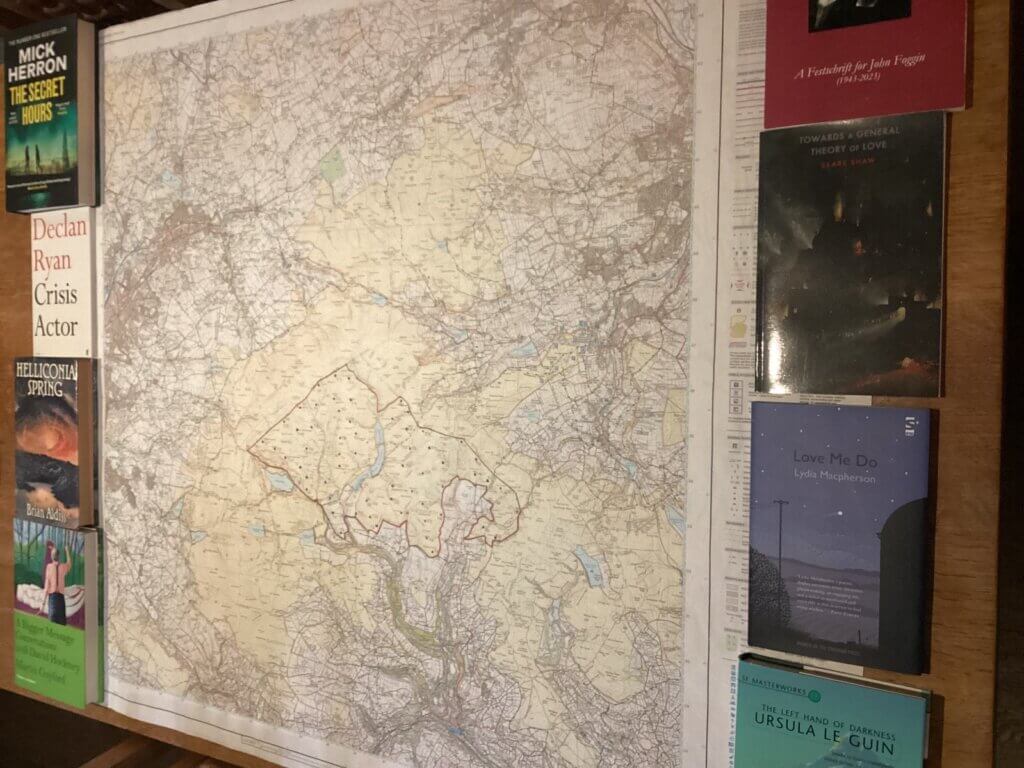

From Withins Height, the whole of CWF will be visible and below is my panoramic visualisation of the whole length of the wind farm. Later in this blog are two visualisations that meet the planning standards, commissioned by Lydia MacKinnon for the Campaign to Save and Restore Walshaw Moor — Stronger Together. Ovenden Moor Wind Farm (150 metre tip height) was used to scale T60 (200 metre tip height) at Cock Hill Swamp, and the other turbines are shown in proportion to distance. Though Withins Height is compact by local standards, I have cropped quite a lot of foreground which I could have filled with a limestone aggregate hardstanding for a 200-tonne crane, and six-metre-wide roads to T45 Dick Delf ahead and T46 Alcomden Stones behind us. The only missing turbine is T44 behind us, whose pylon would fill a whole photograph.

Unless Muttley has one locked in his filing cabinet in Glasgow, this is the first visualisation of the whole length of CWF. If you can do a better job from some other viewpoint, I shall publish it here.

When I started these blogs, I pulled the turbine co-ordinates to 3-figs off Muttley’s layout map. Then I found the RAF had demanded full grid references (MOD comments) and I’ve used them since, softening the drone pilot’s six-figure targets to the SD-and-five preferred by Britain’s most delinquent map, my laminated OL21. With 3-figs, I could fool around with what3words to find Ouija board messages (bribing.signature.paid, midwinter.undulation.civic) but now I get what I’m given by app-creator Jack Waley-Cohen, who also sets the questions on Only Connect. For thirty hours over three days, standing at a windowsill to save my back, I made the panorama above. Only then did I write the usual heading for the blog and ask what3words to find the address: ///sobs.suffer.panoramic really is the universe speaking to Ed Miliband at DESNZ who will be deciding the future of at least 3000 years of sequestered carbon and our international obligations to threatened wildlife.

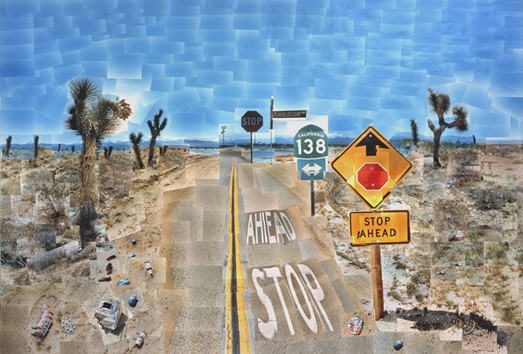

For decades it has been the fruitful thesis of David Hockney that photographs cannot show what we see when we look, a point repeatedly made in the official visualisation guidance. The eye in nature is always skittering (these saccades can reach an angular speed of 700°/s) and the evolved brain smoothly edits this vertigo-and-vomit feed, selecting what is of interest to our intelligence or of necessity for our fear. Although optical focus constantly changes, near and far can both be in focus in the mind’s eye. Hockney made Secret Knowledge on this theme for the BBC: it’s by far the cleverest thing I’ve ever seen on television. Among much else, it explains how Jan van Eyck achieved photo-realism in 1434 in The Arnolfini Portrait. “I’ve wondered all my life how he painted that chandelier”. As with his collage Pear Blossom Highway, Hockney’s idea is that when we look, everything is close. We are ‘inside the world’, not squinting at it through the perspectivist’s peephole with an engraved eye.

Emily Brontë expressed a similar thought in Wuthering Heights. “I’m wearying to escape into that glorious world, and to be always there: not seeing it dimly through tears, and yearning for it through the walls of an aching heart: but really with it, and in it.” And we shall be ‘really with and in’ the meaningless nowhere formerly known as Walshaw Moor, as overwhelmed by turbines as Hockney was by the Arrival of Spring in Woldgate.

We have a mole (‘Pat Pending’) moving in Muttley’s orbit in Glasgow and unknown to ‘Deep Stoat’ who frequents Bannister circles in an old school tie. When Lydia rolled out our campaign map of CWF on the dining table, Pat said, “But it’s fucking enormous, like an offshore wind farm built on land!”

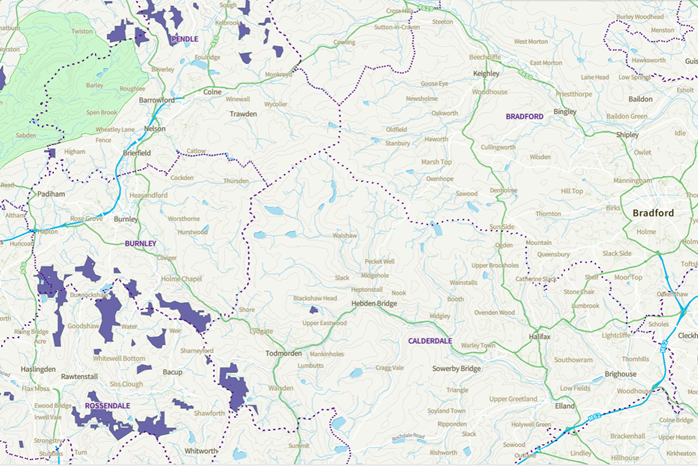

Most of the yellow-tinted CRoW access land on this map and adjacent sheets is doomed if CWF is permitted. If they can build a wind farm on Walshaw Moor, they can build one anywhere. Pat felt that CWF would be cut back to a bunch of clusters. Ovenden Moor is an example of a cluster: nine small turbines with one broken for two years because the absentee landlord says it is “too windy to fix it”. Somehow, the opaque financing mysteriously covers the total loss of 11% of output. Calderdale has set aside land for such clusters, and of course a number already exist and are tolerated or supported by the community. None are on protected peat, because Calderdale Council upholds the habitat laws and understands the carbon science. Community support for the existing Calderdale clusters would increase if E.On fixed Turbine 9 at Ovenden this side of Christmas. Otherwise, we might begin to suspect that it still generates profits even if it never generates electricity.

I don’t believe this cluster idea works in CWF because of the limited access. The clusters would be joined by internal roads leading back to Cock Hill Swamp, and share transmission from Grey Stone Hill to Rochdale, at which point they are one system again and doing the same damage as the whole thing.

I think the reverse is the case: the thing that will appeal to the minister who decides the fate of the sequestered carbon and the internationally important wildlife is the vastness of CWF, and the prospect of another nine dirty power stations on the rest of the South Pennines SSSI, a 650-turbine 3GW array (max output; there will be loads of gas in the background) with 240 miles of crushed limestone roads. This makes CWF the key battleground between nature and our greed for electricity. CWF isn’t ‘clean energy’ because it emits the carbon sequestered in the peat, at a rate incompatible with net zero. Unlike the necessary gas generation required to back up CWF’s intermittency, the carbon plume off CWF cannot be ‘captured and stored’. It was already captured and stored, and the active vegetation was continuing to capture and store until it was scraped off or dried out.

More on this theme another time, but a question to ponder. If you were planning a 3GW South Pennine array, why would you start in the most remote bit and dig an expensive (£36 million) but niddy 132kV cable? CWF repeats all the errors of the Scottish wind farms outside the central belt, which prioritised the greed of opportunistic landowners, but should have started with the transmission system and the sequestered peat. Those same greedy opportunist landowners often felled the greedy opportunistic Sitka monocultures they had planted and which we had paid for, to make room for the greedy opportunist turbines also paid for by us. But CWF is worse than any Scottish wind farm (which are built out of internally quarried stone) because all the aggregate for roads and concrete will have to be imported limestone. The only reason CWF is up for discussion is that the landowner wants to sell.

Visual arguments against any wind farm can be nimbyish. People feel that the view from their literal backyard belongs to them, paid for when they bought their house. Their anger is understandable, but it is counterproductive as an argument in planning, either at the level of Calderdale, or when CWF is called in by Ed Miliband and assessed under the Nationally Significant Infrastructure Project regime, ‘to support quick determination’. There are several-score houses which will get a savage eyeful of CWF, many in Pecket Well, where the Shackleton Ridge will be subdued by four huge turbines like stegosaur tail spines, while fifty more litter the windows of the gritstone cottages. Farmers in Crimsworth Dean will be almost surrounded, like the Siege of Antioch, but their oppression will not generate a milliwatt-second of nervous energy in Whitehall. The one-note “But what about my view” approach of some objectors only does Mr Bannister’s work by feeding the ‘nimby’ catcalling.

That said, local revulsion is a recruiting sergeant for the national and international arguments against CWF. How it looks is telling us that something is very wrong with Calderdale Wind Farm and the visual damage will be to everybody’s views. I think of a commuter under the Scout edge on the Widdop road, whose heart-lifting experience of the gothic sublime at dawn and dusk will be ruined. I think about a woman on the B3 Brontëbus from Oxenhope on a treasured outing to the hairdresser in Hebden Bridge, seeing the moor of her girlhood covered in turbines like cotton grass. I think of dog-walkers on Penistone Hill, whose daily bread of infinity will be poisoned; their dogs won’t really see the turbines, but they will know better than anyone their owners’ sadness: a slump of the shoulders, a turning away from what was once unmedicated happiness, free at the point of use. This is how they harrow the north now: the order goes out from distant Whitehall — “Level Them.”

And I think of Japanese girls and women for whom Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights is a sacred rebellion, and who come in such numbers that the signposts have “Footpath” in shinjitai syllables, though the most recent one adopts a Romanised script and says Arashi Ga Oka: Wuthering Heights. They walk from Haworth Parsonage, these Japanese women, over Penistone, where they first glimpse their destination, across the clapper bridge, and steeply up the rough path where they see it again, framed now by the sides of the beck, whose source is an unfailing spring that from Tudor times watered the Sunderlands at Lower, Middle, and Upper Withens.

After a steep pull up the flagstones they find this post, which gracefully acknowledges their pilgrimage and repays a little of the unlimited courtesy the Japanese show us in their country.

They take the last steps beyond the ruin to the crest where the moor begins. They have been summoned across the world, across two centuries and across a cultural divide that cannot be measured in degrees of longitude, by this:

“My great miseries in this world have been Heathcliff’s miseries, and I watched and felt each from the beginning: my great thought in living is himself. If all else perished, and he remained, I should still continue to be; and if all else remained, and he were annihilated, the universe would turn to a mighty strange: I should not seem a part of it. My love for Linton is like the foliage in the woods: time will change it, I’m well aware, as winter changes the trees. My love for Heathcliff resembles the eternal rocks beneath: a source of little visible delight, but necessary. Nelly, I am Heathcliff! He’s always, always in my mind: not as a pleasure, any more than I am always a pleasure to myself, but as my own being.” Wuthering Heights (1 Dec 1847) by Emily Brontë (30 July 1818 – 19 December 1848) Ch 9.

The Japanese, who have recently had a ten-storey apartment block pulled down before anybody moved in because it blocked a view of Mount Fuji, would be astonished to learn that the English think so little of the achievement of the Brontë sisters that they even consider this wind farm. With its intertwined trees, the ruin of Top Withens in its landscape is as iconic as the Sycamore Gap once was before the sickening vandalism of nihilists with chainsaw blades.

I have thought from the beginning that the ‘Wuthering Heights turbines’ may be withdrawn because of their crass intrusion on an international shrine, but this would make no difference to the destruction of protected peat habitat and red-listed wildlife, nor to the increased danger of flooding in Hebden Bridge. The electricity generated will be expensive when all externalities are accounted for, and with its six-thousand-acre plume of CO2 from the Bronze Age, by 2030 CWF would be the dirtiest power station in England.

Withdrawing T44 and T46 will not stop the nihilist destruction of the panorama of Brontë country either. Only the last section of the photo-montage reverts to a turbine-less shot of Crow Hill and Stanbury Bog, which burst while six-year-old Emily was on the moor with Anne and Bramwell; the explosion was heard in Leeds. The sisters knew the approach to Top Withens as a civilised farmed community. Beyond the watershed was the wild, the unmitigated moorland that is the landscape engine of Wuthering Heights. The sisters often walked into that wild to Halifax, through a thin scatter of toponyms, Mere Stones, Pisser Clough, Foul Sike, so that every turbine site has its own intimate name.

Calderdale Wind Farm will suck the meaning out of this landscape as efficiently as it will drain the peat and dismiss the curlews and lapwings.

Down by Ponden Reservoir, Airedale Teddy and I bump into Frank and Myra, gilded shock troops of the ultra-left, who have a holiday home in the valley; after all, even comrade Stalin allowed himself a modest dacha.

“He looks like one of those push-along dogs on wheels for toddlers! Still campaigning against the wind farm? They’ve got to go somewhere you know.”

“That’s the catchphrase of the landowners, Myra. I’m not surprised to find you in bed with footloose international capital, but I thought better of Frank. Remember it’s SPA peat and a stronghold of red-listed birds.”

Myra looks down her nose at this, as though lapwings voted Conservative out of false consciousness.

“Of course, you have a Tory council here, so that will help you in your campaign against the climate.”

“Three things, Myra. Calderdale and Bradford are both Labour councils; the Tory MP for Keighley refused to come out against the wind farm, so he’s with you; but Calderdale TUC are strongly against.”

In “Some Thoughts on the Common Toad” George Orwell reports similar abuse from the readers of Tribune at any mention of nature in his column ‘As I please’. While Clydeside’s workers were revolutionising ice-climbing with nailed boots and slaters’ axes, and Benny Rothman of the Young Communist League was organising the Kinder Scout mass trespass, the Hampstead Left denounced Nature as a Class Enemy. Which of these opposed strands in socialism does our new Labour government respect?

Never outflanked on her left until now, and disconcerted to be out of step with the trade union movement of which she has been for so long a salaried apparatchik, Myra offers, “What about the climate crisis?”

“When Ed Miliband decarbonises the grid in 2030, Calderdale Wind Farm will be the dirtiest power station in England.”

“But Frank and I adore turbines!”

Frank’s silence may portend an even harsher line on breeding waders than Myra. He projects an aura, to some, of having liquidated several bird-fancying Trotskyites of Orwell’s type during his service in the Spanish Civil War. I explain.

“It’s the peat, Myra. A plume of CO2 from the Bronze Age.”

She laughs.

“Your argument about peat is much too complicated for ordinary people to understand. We are giving them wind farms and they have to go somewhere.”

“That can’t be true, Myra, because you just understood the peat science in three minutes, and you spent some of that time taking the piss out of my dog.”

Like a parody Commissar in a satire by Bulgakov, Myra gathers her comrades, her partner, and her self-esteem and hustles them away from this dangerous Bolshevik.

“Of course I understand the peat science, but I’m not ordinary people!”

Richard Bannister and his oil money backers are not ordinary people either. Why have Frank & Myra, Mr Bannister and Dr Ghazi Osman all arrived at the same destructive attitude to the abundant and fascinating nature on Walshaw Moor? Is this an example of Horseshoe Theory, first observed by Bayard Taylor in 1856?

“In the midst of the debate I was struck by the cordiality with which the Monarchist and the Socialist united in their denunciations of England and English laws. As they sat side by side, pouring out anathemas against ‘perfide Albion’, I could not help exclaiming: ‘Voilà, comme les extrêmes se rencontrent!’ ‘See, how the extremes meet!’”

As Mark Avery put it himself on X:

“Places like Walshaw Moor will be test cases for whether @UKLabour @DefraGovUK @SteveReedMP @hmtreasury @Keir_Starmer @RachelReevesMP @AngelaRayner @mhclg get the environment or not.”

We love imagining that we punch above our weight in international conservation, telling Brazil what to do with the Amazon, bullying Botswana to end trophy hunting, and politely asking the Japanese to stop the bloody whaling. Our Ambassador-to-Nature Sir David Attenborough is the most popular person in Britain, but our wildlife is in a shocking state, and now we are considering coming down hard on our curlews and lapwings to generate high-carbon electricity because a very rich man wants to sell his inconvenient grouse moor, and we will do all these things to set an example to the world.

An example of hypocrisy, moral grandstanding, and submission to inherited wealth.

All should be well. The coalition of ordinary people who love nature is wide. Nature can be a unifying force in England for everyone except the legal and financial suckerfish of Dalek capitalism, and its useful idiots.

“Dirtiest Power Station in England!” I yell after Myra, stranded on the wrong platform of history as the sealed train pulls into Oakworth Station (Daddy! My daddy!) but it is Nature, not Lenin, that emerges from the steam to take charge of the Revolution.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Andy Smith has a diagnosis of autism and dyspraxia and values the moors and fells as a place of refuge and recuperation for his mind and body. He is a keen fell runner, and is often out on the moors and fells, losing himself in their natural beauty. He is keenly interested in nature and local history and how they have shaped each other and society.

When the Wind Farm Came

I remember Top Withens in the old days. The days when I would park at Penistone and look around me, taking in the rolling hills of green with villages in the dips and farms on the hillsides. I turn towards the bleak moors, equally welcoming and unforgiving, depending on how nature feels. I see a group of trees towards The Height, and further along, my eyes take me to a lone tree beside an old farmhouse. I know from experience that this is Top Withens, the farmhouse made famous by the Brontes. This is my destination, where I can clear my mind and reset myself. Some days, I might see a few people; others, I’m the only person for miles.

Living with autism and dyspraxia, these vast open spaces are essential for me. These are places where I can go and switch off from an increasingly non-stop world that seems to be getting faster and faster and, for me, increasingly out of reach as my mind struggles to digest and process everything that is going on around me. I quickly become overwhelmed and withdraw from life, reverting to someone who says little because I am still trying to process what happened hours or even days ago. For me and others like me, the moors are a lifeline where we can go and take in the world at our pace and in our way without feeling pressured, overwhelmed, or confused by the need to try and keep up with a pace beyond me and others.

All that changed when the windfarm came.

The construction of these giant windmills took at least two years, far longer than we were told it would. The moors were a mess. On good days, we were limited to where we could go, security guards stopping us from passing through places where previously we could roam. Fences and machinery further blocked our path, and the constant noise and feeling of being watched made us feel unwelcome from somewhere we used to think of as our backyard of nature. The moors turned into a quagmire of mud, water, oil, and other chemicals we didn’t know a name for. Plumes of smoke rose into the air from all the drilling and lifting. The moors turned into a scene from a dystopian film rather than a place of peace and beauty.

On bad days, when it rained, or the mist came down, and there were no workers or security guards, it was impossible to move with any degree of freedom because the thick, deep mud, oil, and other chemicals created a film of man-made ice, making it difficult to walk on and impossible to run. The moors I once loved had become a sea of mud with nothing growing or living on them anymore.

Now, after the wind farm has been built, the fences pulled down, and the workers and security guards have gone, we are left with a vast tract of concrete blocks separated by thin strips of green. Where I could once go and stand anywhere and see for miles, I now get interrupted views of what was once mile after mile of beautiful moorland, now a steel jungle stretching around Top Withens and far beyond. The noise of the windmills is relentless, their blades whirring nonstop day and night, creating a humming you can’t switch off from that goes right through you and makes you wish for the peacefulness of silence.

Where once I could go and switch off from the world, reset my mind and body, and be at one with nature, I am now constantly reminded of the 24-hour world we live in, the relentlessness of a world I cannot keep pace with as the blades whirr faster than my mind can process their movement. I can no longer go here to find myself. I have lost my place of tranquillity forever, and my world has become much smaller since the wind farm came.

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

This is the 14th in a series of 65 guest blogs on each of the wind turbines which Richard Bannister plans to have erected on Walshaw Moor. Turbines 5, 6, 11, 27, 32, 34, 35, 40, 43, 47, 54, 58 and 64 have already been described. To see all the blogs – click here.

[registration_form]

Poke BD23 4EA into Streetmap and it points to Coniston Cold. (I think Streetmap tries to centralise their arrows on the area covered by a postcode, which isn’t a fixed area).

Near to the Pennine Way. It is landscape of glacial drumlins (if I remember my geological stuff correctly). Also a place where you pass relatively close to the first Otterburn (when heading from the south to north). The Lake District could also be an invoked memory, with both Coniston and Kendal being close by.

A link to the FoE map may have been helpful? But having found it, it appears Coniston Cold is at (or very close) to the centre.