Guest blog – Walshaw Turbine 33 by Anne Caldwell and Nick MacKinnon

Anne Caldwell is a freelance writer and education specialist, based in Hebden Bridge. She has worked for the National Association for Writers in Education, and currently lectures for the Open University as an as well as working as an Advisory Fellow for the Royal Literary Fund. She has published several poetry collections including Painting the Spiral Staircase (Cinnamon Press, 2016). She was the co-editor of The Valley Press Anthology of Prose Poetry, and The Theory and Practice of Prose Poetry, (Routledge), alongside Oz Hardwick. Her fourth collection of prose poetry, Alice and the North, came out in November 2020 and is a love letter to the North of England. Her latest pamphlet is Neither Here nor There, SurVision Press, Ireland. It won a James Tait Prize and was published earlier this year.

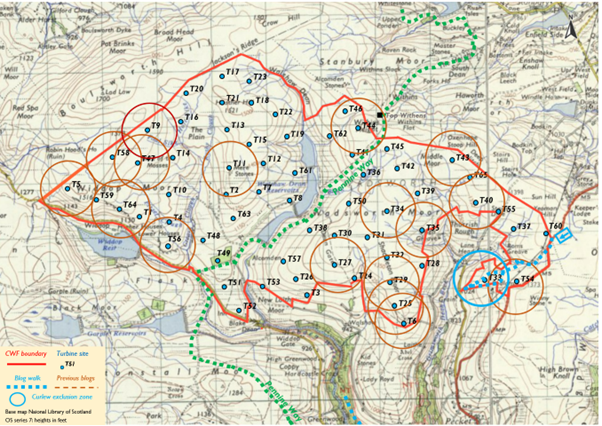

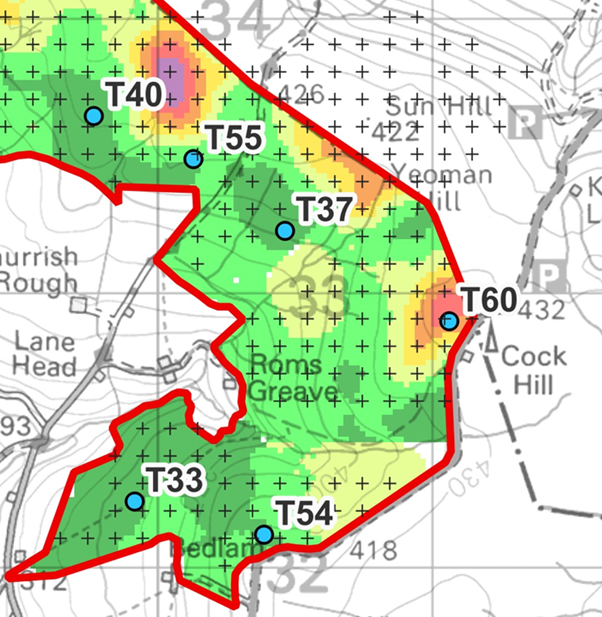

Turbine 33: Grain Slack SD 99916 32240 ///scorched.movie.rents

4 September 2024 I am a poet based in Hebden Bridge and part of The Boggarts, a voluntary group of artists who support campaigns against plans to build England’s biggest wind farm on Walshaw Moor. The group is for green energy but believes this proposal is too big and in the wrong place, a precious landscape and peat bog that stores carbon.

Nick has kindly asked me to choose a turbine site to visit. Turbine no. 33 is based on a footpath off the Keighley main road. On a brilliantly clear September morning, I decided to see if I could find it. I parked up near the University of Bradford’s Oxenhope field site, on Cock Hill. There is a large elephant painted on the side of the building, which always looks rather strange on top of a West Yorkshire moor, but today I think about how endangered elephants have become. They need our protection, just like this landscape. The paint is starting to peel off and red brick is now showing through, which feels like a metaphor for what is at stake. I set off towards a bridleway, that cuts down Half Penny Clough.

The wind is picking up and the ground is surprisingly spongy, considering it is the end of summer. I cut through a mosaic of heathers, bilberry, and mosses, listening to crickets chirping at my feet. When walking on a blanket bog, looking closely at the ground reveals its hidden treasures. Today, the colours are constantly changing in the light: browns, greens, and golds, as well as the purple haze of heather. I walk through banks of common spike rushes, and tussock grasses, bent into the wind.

To my right, there are large ‘peat hags’ visible, so I leave the path just before Roms Clough and go and investigate. There are exposed heather roots, and the uppermost layers of vegetation are breaking up and sliding into a gully. I am joined by a tiny wasp with a bright yellow and black body. As you can see from the second photograph here, nearer the path, layers of exposed peat look like a cliff at the seaside, with striations of different shades of dark brown.

When I return to the main route, I can see that the bridleway follows a man-made drainage ditch. I soon realise that this section of moor is criss-crossed by these ‘grips’ – drainage channels cut into the peat to improve grazing conditions or make the land viable for grouse shooting. There is only one small section of the bog that has not dried out, and this area looks like it was fenced off at some point. I finally find large amounts of sphagnum and a beautiful yellow bog asphodel plant in full flower. My boots are sinking into the marshy conditions and soon I have wet socks and feet. It is worth it to see the range of mosses – I think I can identify star moss and ribbed bog mosses as well as the sphagnum.

If the moor was allowed to return to a more natural state and drainage stopped, it would be able to store carbon well into the future. I have just returned from a trip to Finland, where I visited two incredible peatbogs for an arts project I am running with a dancer, Inari Hulkkonen, and a filmmaker Lewis Landini. We are creating new work in response to peatlands – in West Yorkshire and Finland. The Finnish bog, Punassuo, is not an upland peat bog like Walshaw Moor. It is a eutrophic fen, in a low-lying landscape of mires created after the last ice age but shares many similarities to an upland British blanket bog. It is astonishingly beautiful and has over twenty different kinds of sphagnum including many that are bright red in colour. Punassuo bog is protected because it is part of the national park of Teijo. The land has not been drained, so the sphagnum is thriving. I wonder if Walshaw Moor would be similar in nature if it was restored?

As I slowly plod back to the main path, a kestrel glides in front of me, heading over to the main road to hover and hunt for prey. I can hear running water and find another drainage channel that cuts under the bridleway. There are circular lichen patterns on the stones, like miniature aboriginal paintings.

Roms Clough widens out in front of me and farmhouses are visible across Crimsworth Dean: White Hole, Land Head and Thurrish. A small group of meadow pipits fly up in front of me and start singing from a telegraph wire. I cut through a dry-stone wall into a sheep field. There is an abandoned farmworker’s cottage and barn, with no roof left. I realise from signage that I am following an old packhorse route, but I have missed my turning and must head back up the bridleway. On the hillside opposite I can see some way marker posts that point towards the site of turbine number 33. I cut down Roms Clough to a crossing point over a stream. It is a lovely rust colour because of the peat. Tormentil, a tiny yellow flower, is starring the grasses. I cut up through Granny Hill, skirting round Bedlam Hill. What fantastic place names there are up here on the moor!

The ground is much wetter here, so there is more sphagnum and star mosses. When I crouch down, the mosses really catch the light:

It is slow going, and I must be careful not to slip into a hidden hollow. Soon I reach a field called Grain Slack, and here is the proposed site of turbine 33. It is a gently sloping golden field full of rushes. The afternoon light is highlighting all the russets and browns of the vegetation, and I would be very sad indeed to see this landscape become an industrial wasteland, with many sections concreted over for the turbines. The range of mosses is really special to see:

I talked to Mark Champion, from the Lancashire Wildlife Trust last week and his view was building a wind farm on a peat bog was the worst idea possible and I agree. ‘You might as well run the turbines on petrol’, he remarked.

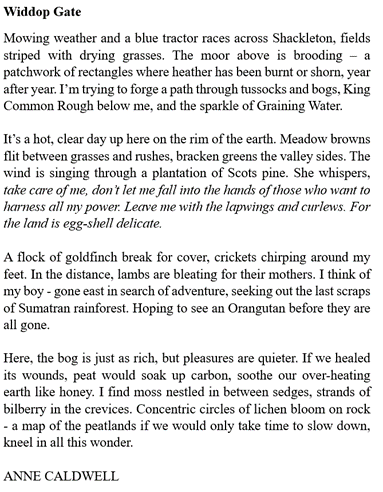

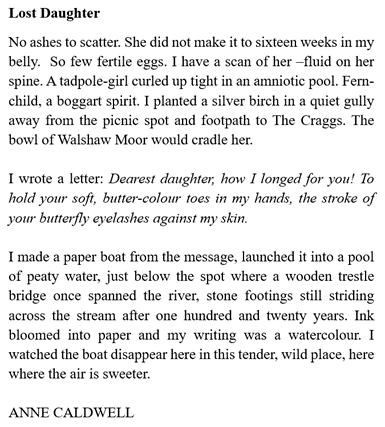

Having seen the beauty of the pristine peat bogs in Finland, I do have a clear idea of what this moor would look like if the drainage ditches were blocked, and the water table allowed to rise to a more natural level. My arts project so far has made me keener than ever to raise awareness of these issues and campaign against the proposed wind farm. To this end, I have started to write some prose poetry in response to visiting Walshaw Moor and Finland. Here are some examples of the work so far.

+++++

Nick MacKinnon is a freelance teacher of Maths, English and Medieval History, and lives above Haworth, in the last inhabited house before Top Withens = Wuthering Heights. In 1992 he founded the successful Campaign to Save Radio 4 Long Wave while in plaster following a rock-climbing accident on Skye. His poem ‘The metric system’ won the 2013 Forward Prize. His topical verse and satire appears in the Spectator, and his puzzles and problems in the Sunday Times and American Mathematical Monthly. Email: nipmackinnon@gmail.com

4 September 2024 Today, True North, Grid North, and Magnetic North fall into perfect alignment by T33, and I am going there with the dog to celebrate. What I don’t know is that Anne has gone there this morning, so the site of T33 has had two visits in a day. Both of us find the ground in the active bog very difficult indeed and we may be the first to come here since the bog ate the path. Perhaps nobody will come here again until Muttley arrives on Richard Bannister’s half-track and tells his minions to start digging a road. Then he will tell his minions to get a tractor to pull him out of the bog, which is deeper than his peat survey shows. He can’t say that Anne and I didn’t warn him. ‘Live for Others’ is our motto.

The OS method of making a flat map of our part of a spheroidal world starts with the 2° W meridian. This becomes the grid line ‘Easting 400000’ that passes just west of Swanage, through CWF at T33, and out to sea at Fraserburgh, finding no more solid land until the north pole. Only on this line is OS Grid North always True North.

The magnetic north pole is one end of the axis of a field generated by currents in the molten iron outer core. In our era, it moves slowly north-east across arctic Canada, which has meant we’ve had to subtract a reducing number of degrees from magnetic to grid north when navigating by map and Silva compass. “Mag to Grid: get rid.” I learned to do it in 1977 when the OS map had the information shown below.

I can’t have been the only teenage navigator to have calculated that magnetic north would be on top of grid north in about 2033. At 14, this event seemed remote as sexual intercourse, England winning the World Cup again, and my old-age pension. I am promised one of these on my 67th birthday, while another has involved a lifetime of disappointment, but the magnetic pole has really got its skis on. The point of three-way alignment is slowly moving north up the 400000 easting and today, true north, grid north and magnetic north will be in perfect alignment 84 metres east of T33 Grain Slack! Nobody is more excited than Teddy the Airedale terrier.

I park at the Elephant on Cock Hill Swamp. The last time I got out here to visit T54 Bedlam Knoll, the bog was pulsating with nesting skylarks and meadow pipits, and I couldn’t hear the road just a few metres down the track. Today it is silent as we cut back into the clough to cross the stream.

Climbing out of the clough, the Airedale applies youth and four-wheel drive and we only meet again because I deploy the emergency recall protocol taught by Paula at Brontë Canine Services. “Get down on one knee, call “Teddy 1, 2, 3, 4, 5” and when he comes, and he will come, give him ten of the best treats you have.” Dog trainers should really be called people trainers, but you knew that.

The path goes through a gate in the fence above Grain Slack, the flattish bog below Bedlam Knoll. My laminated OL21 (whose cartographers are in the final of Britain’s Most Useless Map, held as always at the Crucible) shows it running diagonally across the slack towards the Old Haworth Road. There is a footpath stump in the bog, but it is not waving but drowning, so I stick with the fence southwards, drop west along the wall until Bedlam Farm and then walk ceremonially north along the magical grid line 400000 until I’m near T33.

I am unable to take a photograph that does justice to the difficulty of walking across Grain Slack bog because I am too busy trying to maintain pack-leader status with an Airedale who has started to say, “You’re not from round here, are you?” Would a herd of hairy cows, or Richard Bannister’s flamethrower, improve its carbon sequestration rate? A limestone road, crane hardstanding and turbine foundation certainly won’t. I don’t believe Muttley’s peat map in this area. The nine soundings in Grain Slack report the shallowest peat of all, but it’s an active bog. This eastern section of the peat survey is a dog’s breakfast. If anyone has the kit, it would be good to measure the peat depths in Grain Slack.

A flattening suggests we are at T33. Unusually for CWF, there is a wealth of obvious things on which to take bearings. Scout Moor and Crook Hill wind farms fill the skyline right of Stoodley Pike, but though close, these are on the other side of the enormous OL21: never mind the quality, feel the width. The ruin at Granny Hill and Thurrish farm are easy, and I could have taken many others, but I respect the old Yorkshire proverb:

Man with two bearings knows where he stands.

Man with three bearings is never sure.

My fingers itch to do the ritual twiddle before transferring bearings to map, but no adjustment is necessary! It is a strange feeling of incompletion, perhaps like not having a post-coital cigarette in the 1970s. When the 18th Hebden Bridge Scouts are my age, they will be adding seven degrees (“Mag to grid: raise your bid”) and telling their bored children of the golden age when North was north, and nobody had a surgically implanted Bluetooth transponder in their spinal cords. “But Daddy, everyone at school has got one!”

Will they be doing that on a rewilded moor or a ruined wind farm?

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

This is the 18th in a series of 65 guest blogs on each of the wind turbines which Richard Bannister plans to have erected on Walshaw Moor. Turbines 5, 6, 9, 11, 25, 27, 32, 34, 35, 40, 43, 44, 47, 54, 56, 58 and 64 have already been described. To see all the blogs – click here.

[registration_form]