This is a stimulating book which takes an independent view of Scotland’s Highland landscape. The author challenges the current orthodoxy (is it?) that most of the Highlands was not so long ago wooded and that restoring woodland cover, the great Forest of Caledon, should be an aim of rewilding and nature conservation. No matter if the author is exaggerating others’ positions somewhat, this results in a thought-provoking read. Frank Fraser Darling comes in for some stick.

Fenton thinks that an open moorland landscape is the natural land cover of much of Highland Scotland, and from that starting point he discusses reforestation, herbivore numbers (he is a defender of sheep and has good words to say about deer densities too), whether we need wolves and what is the right future for blanket bogs. He is not a fan of natural regeneration, the spread of Sitka Spruce from plantations, wind turbines on peat soils, bulldozed tracks, the impacts of hydropower, Rhododendron or gorse.

It would be an exaggeration by me to characterise his views as believing that everything went downhill from July 1724 when General Wade was sent north to build military roads to link forts to exert control over the natives, particularly those with Jacobite tendencies. The roads were bad enough, but it was the bridges over gorges and rivers that meant that access to the moorland became so much easier and all sorts of human impacts started or worsened then. He does have a point.

This is a book about landscape conservation from an ecologist with a PhD on Antarctic peat who has worked for the National Trust for Scotland and Scottish Natural Heritage (now NatureScot). I enjoyed it very much and in places it jolted what I thought I knew – I enjoyed that.

The author is stronger on identifying problems than solutions but it would be fair for him to respond by saying that he needs to get people to agree the problems before we could all find solutions.

I recommend this book to upland ecologists and conservationists and also to those who simply holiday in the Highlands or who frequently drive Scotland’s roads.

There are many images through the book, by the author, and these are a considerable asset when considering landscapes, even though they are of variable quality (or of variable reproduction quality). I think a little more thought could have been given by the author and publisher to the deployment and formatting of these photographs, particularly in the eight photographic case studies (all of which were quite convincing and informative). The font for the book is on the smallish size (a common way to keep page number low and cost manageable) but then the photograph captions are even smaller and although I have a fine pair of spectacles I found myself peering more than made appreciation of the images and their captions easy.

Having said that, I think this is a very good member of the Whittles stable of books.

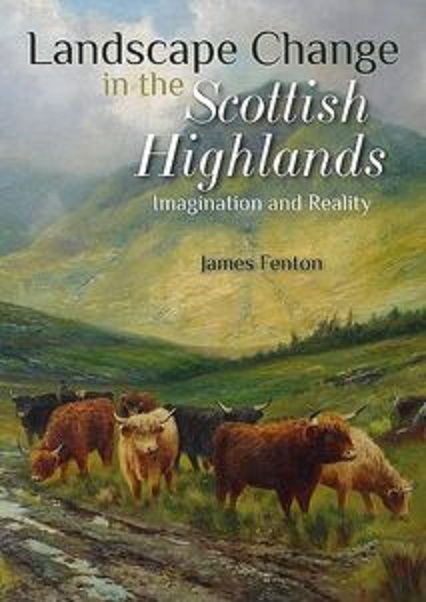

The cover? Highly Highland-appropriate. I’d give it 8/10.

Landscape Change in the Scottish highlands: imagination and reality by James Fenton is published by Whittles publishing.

.

Buy direct from Blackwell’s – a proper bookshop (and I’ll get a little bit of money from them)

Thank you for this mostly positive review of my book, Mark. I am hoping it will get people out of their comfortable ruts, and help stimulate debate about how the Highlands are managed. But, of course, it is easiest just to stick your head down and carry on as normal: challenging established beliefs is just too difficult for most, especially when they have spent their life and career pursuing a given course of action. Hence I am pessimistic about anything changing.

James – I enjoyed your book very much and you gave my misconceptions a jolt.