JANUARY

Velvet Shank:

The Velvet Shank is unusual amongst fungi in that it is a true winter species, thriving in the coldest and darkest months of the year. It is named after the velvety texture of the stems, ‘shank’ here referring to these rather than the more usual meaning of ‘leg’ – as in Redshank for example. The scientific name is Flammulina velutipes, the second part again referencing the velvety stems, while the first part means, rather delightfully, ‘little flames’.

This is a species to look out for if you are heading outside for a New Year’s Day walk. It is one of the very few high quality edible species you are likely to find in the dead of winter. Frost kills most fungi but this species can survive being frozen solid for days, patiently biding its time and awaiting the thaw when it can spring back to life and start growing and reproducing once again.

It grows in groups on dead wood, primarily the old stumps of deciduous trees. Elm was a favourite host so there must have been a glut during the years following Dutch Elm Disease. Today, it has to rely on other common deciduous trees. These were found in mid-December on a huge, gnarled Beech trunk, snapped off about 12 feet above the ground. The caps are twisted and distorted, the result of growing within the confines of a deep, narrow fissure within the surface of the tree.

Because they looked so different from the usual shape of this species I wasn’t completely sure of the identification. To double-check I made use of the excellent First Nature website, sending in my photo and receiving a very helpful email back just a few hours later. I also learned from the website that this species is believed to have anti-cancer properties. Apparently Japanese farmers who cultivate a form of this species known as ‘Enokitake’ enjoy lower rates of death from cancer than the national average. If you are sceptical then try to suspend your disbelief just enough to allow the placebo effect to work its magic.

Wood Sorrel:

This small, delicate plant is easy to overlook with its diminutive stature and uniform pale-green colour, but once you start looking out for it you will start to notice it everywhere. The trifoliate, heart-shaped leaves can be found throughout the year in a wide range of habitats, though it is less common (and less palatable – a bit tougher) during the winter months. Occasionally they carpet small areas of ancient woodland and when they produce their delicately-lined white flowers – often around Easter – they make an impressive sight.

Closely-related plants in North America are known as ‘sour grass’ and that gives a clue to the taste. The small leaves have a surprisingly strong, sharp tang to them, not unlike lemons though not so overpowering – more likely to induce a slight wince than a screwed-up face.

I’ve never been more adventurous than to graze on the leaves during a walk but you could use them in salads to spice them up a bit, or even try adding them to more savoury dishes to enhance the flavour. The leaves are high in vitamin C but, as suggested by the generic name ‘Oxalis’, they also contain oxalic acid so it is best not to overindulge.

Scarlet Elf Cups:

These are, admittedly, towards the gimmicky end of the wild food spectrum but they are indeed edible (despite what some older books say) and they are so startlingly attractive that I think they deserve a mention. And, actually, they don’t taste too bad at all if cooked for long enough to soften them up a little. They have a major advantage in that they appear during the coldest months of the year, adding vivid splashes of colour to the largely monochrome landscape and brightening up the leanest period for foragers.

They are very frequent in this part of Devon and, generally, they tend to be most common on the damper, western side of the country. They often root to dead and decaying wood and are usually found in little clusters or even in a line, mapping the presence of a fallen branch, hidden in the leaf litter below. I also find them growing on living moss-covered grey willow branches near to the ground – the red fungi and bright green moss making for quite a contrast.

They are very frequent in this part of Devon and, generally, they tend to be most common on the damper, western side of the country. They often root to dead and decaying wood and are usually found in little clusters or even in a line, mapping the presence of a fallen branch, hidden in the leaf litter below. I also find them growing on living moss-covered grey willow branches near to the ground – the red fungi and bright green moss making for quite a contrast.

They look fantastic in the wild and I’m reluctant to pick more than a handful very occasionally. But they do also work their magic on the dinner plate. A quick online image-search reveals all sorts of clever concoctions involving other food items, imaginatively arranged within the bright red cups. If you are interested in fungi as food you should probably eat them at least once. But, after that, maybe they are best left alone to grace the woodland floor.

Navelwort:

This distinctive member of the stonecrop family is common along hedgerows, pathways and springing up from crevices in walls and rocks. It is mainly restricted to the south and west, and seems to be especially abundant close to the sea – the long-distance south-west coast path is a great place to find it. If conditions allow (which this year they do) it can be found throughout the winter, as well as in the warmer months.

It’s an easy plant to overlook when growing amongst other vegetation; its muted, rather uniform, green leaves helping it to blend into the background. When growing in isolation on walls or rocks it is rather more obvious, with the navel-centred leaves standing out boldly against the bare substrate.

It is sometimes known as Wall Pennywort. The young leaves are barely modern-penny-sized but when full grown they are a little larger than the old Victorian pennies which no doubt led to this alternative name. The addition of ‘wort’ is common in plant names and suggests a former use as food or, more especially, as a treatment for ailments or disease.

The leaves are interesting to snack on because of their fleshy texture rather than the taste. They are full of water and satisfyingly crunchy when the leaves are fresh, not dissimilar to thinly-sliced cucumber. They are particularly refreshing during a long winter walk along the coastal cliffs, after storms have coated each leaf with an invisible sheen of sea salt, adding welcome bite and flavour.

FEBRUARY

Sheathed Woodtuft:

I’ve taken a few calculated risks when eating wild fungi over the years but with this recent find I inadvertently pushed the limits well beyond my comfort zone. They were growing low down on a pile of cut logs at the edge of an old meadow. I initially thought they were Velvet Shanks, a common winter species I have eaten before, so I took a few home. To be extra careful I made a spore print by leaving one of the caps on a piece of paper, under an upturned coffee mug. After a few hours enough of the spores had fallen from between the gills to leave a delicate, pale-brown trace on the paper. So, these were not Velvet Shanks after all, as this species has a white spore print.

Further investigations, mostly online, eventually turned up an exact match for the Sheathed Woodtuft, not something I’d come across before but apparently an excellent edible species. I checked and double checked, and checked again, and put them in the frying pan. And very nice they were too.

A few hours later I stumbled across a reference to a deadly poisonous look-alike species. The Funeral Bell has a name that is equally as disturbing as the better-known Death Cap, and for very good reason – it shares the same deadly toxins. Alarmingly, a couple of websites suggested that the edible Sheathed Woodtuft and the decidedly inedible Funeral Bell could appear so similar that on no account should the edible one be risked. Whilst I was still confident of my identification, sufficient doubt had crept into my mind to make the next few hours pass rather slowly and uneasily.

I’ve read plenty of grim stories about wild food gatherers coming to grief through misidentifications. It’s easy to feel rather smug and tell yourself that you would never be so foolish. This episode was a reminder that the potential for mistakes is never far away, and, if you make one, you may not get a chance to learn from it.

Tadpoles:

The second half of winter is perhaps the least productive time of year for foraging. Spells of cold weather have eliminated all but the hardiest of wild flowers. Most of the nuts and berries have been consumed or have rotted away. There are a few winter season fungi but many of those seem to fade from the scene as the winter progresses. While the first signs of spring are already apparent, the new growth from the early-flowering edible plants has yet to result in anything tangible.

Locally, one of the most obvious signs that spring is not too far away is a huge production of frog spawn. From mid-January the clumps of black-dotted jelly start to appear, with more and more added as the weeks go by. It seems that almost any patch of water at least a few inches deep is a potential spawning site. Dozens of small rain-fed pools on the local moor now contain spawn and in the more intensively-manged pasture fields, gateways are a favoured site. Poaching by cattle and wheel ruts from machinery create depressions that readily hold water during the winter.

Strangely, the frogs themselves are not much in evidence, except for an occasional road casualty – presumably all the action happens overnight.

By March, the clumps of jelly have been replaced by living streams of writhing black tadpoles. Then, over the next few months, there is tadpole Armageddon. The losses are immense as temperatures rise and sites start to dry out. As farming activities increase in the spring, few of the field gateway sites remain viable even where water remains. Ironically, the same animals and vehicles that created these spawning opportunities now return to exact a terrible revenge.

No doubt there are further losses due to predation and sometimes, at this leanest time of year, even humans get tempted. The young Chris Packham was unable to resist trying them and Nick Baker mentions them in a chapter on taste in his recent book. Famously, the chair of the GWCT felt obliged to write to The Times in alarm that children might take up the habit and start to impact on frog populations. A basic understanding of ecology and the fact that they taste a bit like semolina would suggest that his fears are unfounded.

MARCH

Wild Garlic:

Wild Garlic, or Ramsons as it is sometimes called, is one of the most eagerly awaited plants of the spring for its aesthetic appeal and for its flavour. By late April it carpets the floor of ancient woodland where conditions are right, a haze of white flowers among the long-established green leaves. It is often found in the same place as Bluebells, and the flowers usually peak at about the same time, producing a dazzling display.

All parts of the plant are edible though it is usually the leaves that are eaten. They are at their best when newly emerged and tender in the early spring. The fresh leaves in the image were covered with snow just a few days previously and the remnants of deep snow drifts on the narrow country lanes made it tricky to reach the wood.

The strong garlic smell is most apparent when the leaves are crushed. This is a handy for confirming the identification as some superficially similar spring plants contain unpleasant toxins for self-defence; they are emerging at a time of year when any fresh growth is highly appealing to herbivores worn down by the rigours of winter.

The way the scent of garlic is released on crushing suggests that this too is a plant defence, deployed to its fullest extent when under attack. It seems to be very successful judging by the dominance of the plant in favoured locations. It works well in deterring some humans too, though for those who do enjoy eating it, it is beneficial rather than harmful, acting as an antioxidant and apparently helping to reduce cholesterol levels. It is also reputed to lower blood pressure, as does the gentle stroll through the woods to find it.

The taste is less overpowering than garlic cloves from the supermarket and goes especially well with tomato and cheese. Try a few leaves in a sandwich and you might find yourself adopting an annual ritual in the first few days of March, scouring your local woods for the first new leaves of the year.

APRIL

Common Sorrel:

Many common garden ‘weeds’ are technically edible but hard to get excited about. The Dandelion is perhaps the most abundant and is no doubt very good for you but the leaves are undeniably bland. Common Sorrel, another widespread grassland plant prone to appearing on unkempt lawns, at least has a bit of bite to it. The taste of the fresh leaves is often likened to apple peel – pleasant enough, if rather chewy and with a slightly acidic kick.

This plant is in the Dock family and unrelated to Wood Sorrel, despite the fact that both species share a sharp, acidic edge to the flavour. On looking it up it turns out that they both contain oxalic acid, presumably as a defence against insect pests and grazing animals. It is also toxic to humans but in quantities sufficiently large that the casual forager need have no concerns.

The leaves of Common Sorrel are distinctive once you get your eye in – arrow-shaped with obvious pointed lobes at the base. The close relative Sheep’s Sorrel can look similar but is also edible and tastes much the same. The leaves share another trait with apples in that while most are green, a few appear bright red, as if prematurely anticipating the autumn.

Golden saxifrage:

There are two similar species of Golden Saxifrage known as ‘opposite-leaved’ and ‘alternate-leaved’, the names helpfully highlighting their main distinguishing feature. This one is opposite-leaved and it is very common locally, forming a low, dense carpet in patches of woodland with heavy, waterlogged soils. It acts as a handy warning that you risk a boot-full of muddy water if you venture too close.

It is an adaptable plant and grows throughout Britain from the lowlands to wet flushes in the mountains of the far north.

The leaves can be found throughout the year and the subtle pale yellowish flowers (just visible in the photo) appear in early spring.

The leaves are crisp and succulent though they do have a rather bitter, unpleasant taste to my mind, at least when eaten raw. A French name ‘cress of the rocks’ seems to be pushing its culinary virtues to the limit, though perhaps the French are a bit more inventive with the way they use it.

MAY

Cuckoo Flower:

Otherwise known as Lady’s Smock this is one of our most attractive spring flowers, brightening up damp pastures and roadside verges across the country with its subtle pink flower-heads. It usually starts to appear around mid-April, about the same time as the first Cuckoos arrive back from Africa – hence the name.

It also appears at the same time as Orange Tips are emerging, which is just as well as it is one of the main foodplants for this butterfly’s caterpillars. The ‘orange-tips’ of the male butterfly warn of its distastefulness, and this is derived from the spicy mustard oils within the Cuckoo Flower (and some of its close relatives). Spring butterflies also take advantage of the nectar.

In the best areas, Cuckoo Flowers can produce an impressive display, forming a pale, shimmering haze across the fields as thousands of unsynchronised flower-heads nod and sway in the breeze. It disappears if grassland is drained or managed too intensively but it seems reasonably resilient overall. Last year it was abundant in the damp, rushy pasture in front of our house, until the farmer turned his cows loose in May and they were eaten (or perhaps trampled) to oblivion within a few days – yet they are back again this year.

Rather disappointingly, the Cuckoo Flower doesn’t make PlantLife’s list of species that are OK to pick though it must surely have come close to qualifying. I don’t think they’d mind if you took a few flowers from a place where it is still common. It’s a great plant to try with young children because they love the idea of eating flowers and the petals have a distinctive hot, peppery taste. As they are munching you can explain that our prettiest spring butterfly depends on this plant for fuel, to keep it safe from hungry birds and as a site to lay its eggs.

Garlic Mustard:

As suggested by the name, this cabbage-relative has two flavours for the price of one, though the garlic comes across rather more strongly to my mind. The leaves are actually tasteless until they are crushed or, if you will, ‘tasted’. The chemical reactions producing the strong flavours only take place (as a defence mechanism) once the foliage is under attack. It’s a bit like Schrodinger’s cat – the act of tasting destroys our ability to perceive the plant’s tastelessness.

I always think of it as a rather poor substitute for Wild Garlic but with the advantage that it is abundant and widespread along verges and hedgerows. If you fancy a quick garlic-flavoured nibble and are not lucky enough to be near ancient woodland then this is your best bet.

It is at its best early in the summer and the leaves become increasingly tough and tattered as the season progresses and hordes of hungry invertebrates take an increasing toll. Even the fresh leaves look as if they have had chunks bitten out of the edges giving them their distinctive shape. Could this also be a defence mechanism – a deceptive message that this plant has already been started so please move along and find something else where you will have less competition?

JUNE

Mint:

The smell of mint induces a feeling of nostalgia in me that no other plant can match. One of the few jobs I was trusted not to mess up as a small child was to go out into the back garden to gather a few springs of mint for the Sunday roast. It must have been the first plant I learnt to recognise and put a name to, and 50 years on the scent still takes me back to that distant childhood. Perhaps that memory also helped foster a belief that nothing connects people with wildlife more than the hands-on approach of interacting with it.

There are a number of different wild mint species that all look rather similar, especially before they begin to flower. They also hybridise readily which makes things even more complicated. I’m afraid that as a non-botanist I tend to lump them all together. This one might be Water Mint but I wouldn’t put money on it. Thankfully, so long as a plant looks and, more importantly, smells like mint then it is safe to use.

As well as its traditional use to bring out the flavours in roast lamb, the leaves make a refreshing drink. It’s a nice way to end a walk if you can locate a handy patch of plants as you near home. Just nip off the uppermost whorls of leaves from two or three plants and add recently-boiled water. The flavour intensifies as the leaves continue to stew so remove them once you find a taste that suits your palette.

Dryad’s Saddle:

This is a common and widespread bracket fungus often found in the summer on dead or dying deciduous trees. It can grow to a huge size, perhaps as large and heavy as any British species. The problem is the large and easy-to-spot specimens are not much use as food as they quickly become tough and unpalatable. The trick is to find them while they are still very difficult to find.

It has something of a mixed reputation as an edible species but I’ve found the young ones to be very tasty and they often grow at a time when few other fungi are available. The shape of the caps and the distinctive pattern of concentric circles of darker scales means that it is hard to confuse with anything else.

The name comes from its apparent co-option by horse-riding wood nymphs. As an ornithologist (and realist) I prefer the alternative name of Pheasant’s Back, a reference to the pattern made by the scales on the cap’s surface. The shape of the caps is also sometimes compared with the seat of an old-fashioned tractor – from distant days when farmers had to make do with a small, hard piece of plastic outside in the elements, rather than the cushioned comfort of today’s weather-proof cabins.

Pignut:

Pignuts are umbellifers (in the carrot family) and are like miniature versions of the more familiar Cow Parsley. To help confirm the identification, look closely at the finely divided leaves, especially those towards the base of the plant. If you grow your own carrots you may notice the similarity in leaf structure. In favoured meadows and woodland rides Pignuts can cover large areas, softening the landscape with their delicate white flower-heads.

This species was much loved by rural schoolchildren in the days when they were able to recognise useful wild flowers. It’s easy to imagine the pleasure they would have gained from rooting up the small edible tubers – especially in times when food was hard to come by and tended to be bland and repetitive.

It’s harder than you might think to locate the nut-like tubers, especially in heavy soil and if you are trying to do the job carefully so as to cause as little disturbance as possible.Ideally, you want to trace the stem of the plant down through the soil until you reach the ‘nut’ still attached to the plant. This helps to ensure that what you are about to eat is indeed a Pignut. The bulbs and tubers of other species, often found in close proximity, can look surprisingly similar and some are poisonous.

Once the Pignut tuber has been retrieved you can rub off the outer coating, which helpfully removes all the encrusting dirt,and eat it raw. The taste is not unlike that of Hazel nuts (a definite positive) with a slight aftertaste of celery (not so positive).

These plants were on one of Devon Wildlife Trust’s reserves so were not available for exploitation and it’s worth noting that landowner permission is needed before digging up any wild plant. The local Badgers are happy enough to ignore the rules and have rooted through large areas on this site to dig out the tubers. I’ve often noticed this Badger ‘damage’ locally and pondered its likely effects on the vegetation. As with all such impacts no doubt it is very good for some things but has a negative effect on others. Across a large site it must surely help to maintain a diversity of different types of vegetation. It certainly helps put in perspective the loss of the occasional plant due to human foraging.

JULY

Raspberry:

This is one of the best of all wild foods – one that can be found widely, if rather sparsely, across most of the country.

If they are not quite a match for the taste of wild strawberries (though these things are highly personal) the plants do at least produce good-sized fruits, approaching the size of the smallest cultivated raspberries. This similarity leads people to believe they are escapes from cultivation, even when found well away from civilisation. To the contrary, this is a genuinely wild, native plant, with a long history, and is all the more enjoyable for that.

The plants are not defended as heavily as brambles and the small thorns are less likely than their thuggish relative to shred your skin, or even your clothes, during the gathering process. Another advantage is their early season. The ripe fruits appear well ahead of the ubiquitous blackberry, from late June onwards in a good year. Now is the perfect time to look out for them in sunny woodland clearings, and along tangled, overgrown hedgerows.

—————————————————————————————————————————

Finally, any guesses as to the identity of this plant as described in three recently-published books on wild food?

‘…leaves and shoots make an excellent addition to fresh salads or can be cooked with spinach and other vegetables.’ (2018)

‘Don’t worry about their furry texture; this disappears completely during cooking. […] The young leaf spears, picked in March…make excellent salads, not unlike sliced cucumber.’ (2012)

‘…it is now considered to be quite seriously poisonous, causing dangerous liver conditions and even liver cancer.’ (2010)

Happy foraging.

Bilberry:

I used to think of the Bilberry (often Blaeberry north of the border) as an upland plant – something available for browsing in high summer when crossing wide expanses of heath or moor. In recent years I’ve found it along local hedge-banks and within deciduous woodland in the dairy and sheep country of the lowlands, as well as up on the higher ground of Exmoor and Dartmoor.

The problem with the lowland plants is the difficulty in finding any of the wretched berries. The plant itself is common enough, sometimes carpeting large areas. And the pinkish, globular flowers are very obvious in the spring, hanging down from their stalks and promising good things to come. And yet, later in the season, ripe berries are few and far between. Perhaps losses to birds and small mammals are greater away from open moorland? Adding to the problem, the dark colour of the ripe berries helps them melt into the background making those that do survive devilishly hard to spot. Small children are a useful search tool with their keen eyesight, willing attitude and proximity to the ground.

The supermarket equivalent of the Bilberry is the well-known and heavily-cultivated Blueberry which is larger, brasher and (it goes without saying) inferior in taste. These berries have gained a reputation as a ‘superfood’ in recent years, full of such apparently good things as antioxidants and phytoflavinoids, and sold on the basis that they can ward off almost all known ailments and diseases. They even have anti-inflammatory properties which may help with the sore back you are sure to develop during the protracted gathering process.

Wild Strawberry:

This is a delightful plant, especially at this time of year when there is every chance it will be dripping with irresistible red berries. It has the sharply-serrated, trifoliate leaves typical of all strawberries, and delicate white flowers which give way to the perfect, albeit tiny, red fruits. In all respects it is a diminutive version of the more robust cultivated strawberry.

It tends to grow in small clumps and favours poorer soils where it is not swamped by more vigorous competitors. In much of our nutrient-soaked countryside it risks drowning under tall grasses and Cow Parsley, and the berries can be hidden from view even if the plants cling to survival.

The fruits are often available for just a few weeks each year (which adds to their appeal), though it is possible to extend the season if you can find them growing in different situations. Much like Bluebells and Primroses, plants growing within the shade of woodland can be well behind those in a more open situation. To prove the point these two photos were taken on the same day. Within a local wood the plants are flowering and the berries have yet to develop. Nearby, on a sun-drenched roadside verge, the flowers are long gone – and the berries soon will be too.

The taste is just what you would expect from a strawberry – perhaps a little sweeter and subtler than the cultivated version but every bit as pleasant. You will need to pick several to get a good sense of the flavour. And perhaps 10-12 would be needed to match the volume of just one typically-sized supermarket strawberry.

To end with a quote stolen from John Wright’s excellent Hedgerow book in the River Cottage series – ‘Doubtless God could have made a better berry, but doubtless God never did.’ So said a Dr William Butler in the seventeenth century and, some 400 years later, it’s hard to argue with him.

AUGUST

SEPTEMBER

Hazel Nuts:

This is one of my favourite wild foods and between early August and October (in a good year), I don’t go for many local walks without risking my teeth and cracking open at least one or two. The Hazel would have been one of the first trees to recolonise Britain following the last ice age and it’s easy to feel something of a connection with ancient landscapes when eating the nuts – animals (including people) have been doing the same thing, in much the same places, for thousands of years.

In modern Britain too, you will face some stiff competition – so much so that it’s a rare treat to find a fully ripe, deep-brown coloured nut in October. Usually you have to gather them earlier in the season when the shells still have some green in them (like the ones pictured in early-September), though they still taste delicious. It’s not fellow humans that are pinching them these days although humans are, indirectly, to blame. It’s introduced Grey Squirrels that do the damage and if you are too late reaching the trees they will be bare, the nuts transformed into a dispiriting clutter of split shells on the ground below.

Grey Squirrels are so effective in their depredations that I wonder what the impacts might be on native species that also enjoy these nuts – the declining Common Dormouse for example. It also makes me wonder whether our native Red Squirrels were just as efficient at nut harvesting before they were pushed out by the Greys. Perhaps someone lucky enough to live in a place where Red Squirrels are still hanging on knows the answer?

Mackerel:

The summer and autumn months bring Mackerel shoals close inshore around much of our coastline. They are like miniature tuna and roam the seas in hungry packs looking for baitfish, snapping voraciously at anything that moves – even a brief pause for reflection would result in the loss of a meal to the other fish nearby. That makes catching them unbelievably easy (if they are there). You don’t even need bait – hooks next to coloured feathers or bits of glinting silver foil work perfectly well.

The only real trick to Mackerel fishing is finding deep water close enough to the shore to cast into. Piers or harbour walls (or boats) are good places though you may have to share the space with other fishermen. Better still are more remote rocky headlands, provided you can find a way down to the water’s edge.

The fish pictured here were caught on a family holiday in north Cornwall, not far from Tintagel, in early September. The scenery was spectacular and to add to the pleasure of fishing we watched a family group of Peregrines trying to catch a Fulmar offshore. I was reminded that my children still call Fulmars ‘Flemers’, something that started several years ago on a trip to Shetland – a combination of mishearing the name and being told these birds could spit a foul-smelling oil at you if you strayed too close to their nests.

You can freeze Mackerel to eat later but this is one fish that tastes far better on the day it’s caught. Barbecuing on the beach is perhaps the perfect way to cook them to ensure the maximum possible freshness and as an excuse to remain outside at the best time of day as the light starts to fade.

To end with a plea. I have never understood why it is normal practice to humanely kill game fish caught in freshwater, and yet it is apparently acceptable to allow sea fish to flap around on the rocks until they die. It’s just one of those strange cultural quirks I suppose, though lacking in any logic that I can see. They should be all be afforded the same respect and killed as quickly as possible.

Chanterelles

Here in mid-Devon, the relentless wet weather means there is currently a bumper crop of Chanterelles. They are relatively easy to find (they almost seem to glow and can be spotted at a distance in even the gloomiest of woodlands) and they are difficult to confuse with anything unpalatable – though do, of course, check carefully using a reliable book or website. Try woodland with oak or beech trees and look along ditches or hedge-banks rather than wandering into the middle of a large expanse of forest.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, they are one of the top two or three fungi species in terms of taste. On the continent, people have been known to come to blows over a profitable patch of Chanterelles though in my local countryside I have yet to encounter anyone else with the slightest interest in them or found any evidence that others are gathering them – which is great, or a bit depressing, depending on mood (and availability of Chanterelles).

They take about 6-7 minutes to turn into lunch and cooking them is as simple as adding butter, olive oil and garlic to a frying pan, cleaning away any obvious dirt or grit and lobbing them in – small ones whole, larger ones cut into pieces. Then just add to toast. If you don’t like the result then at least you will have found out something useful – foraging for wild fungi of any kind is probably not for you.

OCTOBER

Penny buns:

These delightful fungi are also known as Ceps or Porcini but I prefer Penny Buns because, well, because they look just like them, even if the price has gone up since they were first named. This is arguably the most esteemed of all the wild fungi and they fetch a high price at local markets just across the channel.

These delightful fungi are also known as Ceps or Porcini but I prefer Penny Buns because, well, because they look just like them, even if the price has gone up since they were first named. This is arguably the most esteemed of all the wild fungi and they fetch a high price at local markets just across the channel.

It can be hard not to break into a spontaneous grin if you round a corner to find a group of them popping up from the ground in front of you. Due to the persistent wet weather, I’ve been grinning rather a lot this autumn. They grow under a variety of different trees and, as with many fungi, they tend to be most common in edge habitats such as verges, path sides and along hedge-banks.

There are some look-alike pitfalls for the unwary though nothing that will do worse than spoil a good meal. And once you get your eye in they are really quite distinctive.

They keep well if they are dried and so can be enjoyed right through the winter, long after the first hard frosts have brought the season to an end.

If they have a drawback it’s that they are prone to infestations of maggots – the larvae of gnats or flies. Wild-food foragers have very different tolerance thresholds for these things. Some are prepared to turn a blind eye to a few small interlopers, whereas others will confine the day’s pickings to the dustbin at the first hint of trouble. With Penny Buns, it’s as well to persuade yourself towards the former camp if at all possible.

Parasols:

I’m normally fairly relaxed about the idea of collecting small numbers of fungi for the pot. The structures we see above ground are the fruiting bodies produced by the main mass of the fungi, safely tucked away below ground. The analogy is not perfect but it’s not too dissimilar to picking blackberries – taking a few of the reproductive organs but leaving the main plant intact. Of course, there are other creatures that make good use of berries and fungi so hoovering up vast numbers is not on, but taking a few seems reasonable enough to me.

The Parasol is a little more tricky. It’s partly the fact that it tends to grow in wide open, often publicly accessible, spaces, such as here on cliff-top grassland in north Devon – close to the well-used south-west coastal path. They often reach an impressive size, sometimes approaching dinner-plate proportions and on a tall stem so that the caps are thrust above the surrounding grasses and visible from miles around. When they grow in numbers (as they often do) they make for a very impressive sight, and there-in lies the problem. Is it right for one person to diminish a spectacle that others might enjoy?

My answer varies, depending broadly on hunger levels. I will sometimes take the odd one but I try to leave the troop largely intact. If I take two young ones out of 40 then I don’t feel too bad, though, of course, it would only take 19 like-minded people to clear the crop completely. As I said, these things are tricky.

My culinary skills don’t extend much beyond ‘putting things on toast’ so these are perfect – they don’t even need to be cut up if you can find a nice slice-of-bread sized specimen, and they have a strong, nutty flavour.

This is a species that does have some nasty look-alikes though none grow to anywhere near the same size – as always, check carefully, and if in any doubt, stick to picking only the largest individuals.

Puffins:

I’ve not eaten this species as yet but that’s partly through lack of opportunity. I’ve yet to visit Iceland where they are often on the menu and are, apparently, readily available in supermarkets.

It’s interesting that the idea of eating this bird instils horror in people who might be happy enough to eat duck or goose or pheasant. On the face of it, Puffin as a food source has quite a bit going for it. They are abundant (in the places where they are taken for food), they are about as free range as it is possible to get, and because they are netted at breeding colonies, rather than shot, a meal does not come with the risk of denting your teeth – or your intelligence. It’s not pleasant that anything has to be killed just so we can eat it but if I had to choose a way to go then netting followed by humane dispatch would be right up there. Not least, it’s all or nothing. You are either caught and killed, or you escape unharmed; there is no chance of wounding followed by a prolonged and painful death as unavoidably happens so much of the time with shooting.

This, I think, is an example of System Justification Theory whereby we automatically and subconsciously adjust to, and are therefore more likely to accept, the status quo. Shooting Mallards or Rabbits to provide food is seen as more acceptable than killing Puffins for no other reason than that it has been happening here in Britain for a long time and we have all got used to it. The same thing helps to explain many of our responses to the exploitation or management of wildlife. Think about the outrage generated by the licenced killing of a few Buzzards compared with our far more relaxed attitudes towards the routine annual destruction of thousands of Carrion Crows and Magpies (birds that are far more intelligent). We might not support this killing but we tend not to get so worked up about it. Why should there be this difference?

I’m not suggesting that we start to eat Puffins (or, for that matter, allow more Buzzards to be killed). I’d see it the other way around; the theory helps to explain why change to current practices is so hard to achieve even when all the arguments are heavily stacked in your favour. Imagine trying to justify the introduction of a new sport called driven grouse shooting or a new proposal to release 40 million non-native chicken-sized birds into the landscape every year. Everyone would laugh at you. And yet, here we are, with most of the population seemingly content to live with both.

Blackberries:

No series on wild food would be complete without the humble blackberry and there can’t be many people who haven’t picked and eaten them at one time or another. Parents who are wary (or unaware) of almost all other forms of wild food will happily send their kids out blackberrying – at least that used to be true a generation ago. The bushes have a happy knack for brightening up some otherwise dull and wild-food-less places and even in urban areas or the most intensively-managed farmland a short walk is likely to pass by a bush or two.

They have a long season. The pioneers ripen as early as June in some years and berries can be found well into the early winter in mild conditions, though the taste does tend to deteriorate as moulds and increasingly hard-pressed wildlife take their toll. It’s not just insects, birds and small mammals that relish them. I once watched a Roe Deer working along a hedgerow, pausing often to delicately select and remove the ripest berries from the ends of the shoots. It looked almost as if it could make use of an empty ice-cream container.

A bit like exotically-coloured but commonplace garden birds, you suspect our appreciation for blackberries has been dulled by their ubiquity. The human brain seems to relish a challenge and something that is ridiculously easy to find quickly becomes less appreciated, however good it looks – or tastes. Which is a shame but, I guess, unavoidable.

If they have a drawback it’s that they don’t keep well unless frozen. So, whilst they can be added to cereal to brighten up the first meal of the day you have to go out and pick them that morning – or perhaps the day before. They also make a good addition to ice-cream, and crumble is hard to beat on a cold winter evening if you’ve taken the trouble to freeze some from the previous autumn (and know someone who can make it).

It turns out that the blackberry is actually a bewildering variety of hundreds of different microspecies. Keen botanists can apparently sometimes work out the county of origin if provided with a sample from a plant. If anyone cares to hazard a guess from the photo I’d certainly be impressed with anything close to a correct answer.

Sloe gin:

I do admire people who manage to produce their own wine from flowers, fruits or leaves, gleaned from the countryside. It seems to require lots of faffing about with all sorts of different ingredients, and endless decanting of fluids from one vessel to another – followed by a long, nerve-wracking wait to see if it has worked. I’m sure it’s easier than it appears once you get the hang of it. But in case you never do, I’d recommend sloe gin (or even sloe vodka) as an altogether simpler alternative.

Despite what you might read, making sloe gin really is as easy as picking the sloes in the autumn, adding them to a jar or bottle and tipping some gin on top. Unlike wine making there is very little to go wrong.

At the risk of contradicting myself I’ll add a couple of very quick caveats. You can add sugar and almond essence to the mix when you start, to sweeten the end product, something that does greatly improve the taste to my mind. If the sloes are still quite hard when picked then it’s worth pricking them to help allow the flavour to seep out. Some people apparently spike them with one of the defensive thorns, handily provided by the Blackthorn bushes, as they are picked. But if that seems like a lot of hassle you can avoid it; just leave the picking until after the first significant frost has done the work for you by softening the fruits – mid-October is often the perfect time of year.

Ideally, sloe gin needs to be left for a few months at least and the longer you resist temptation, the more the flavour intensifies and the better it gets. Making it in October for Christmas is fine if the holiday spirit means you can’t wait any longer, or there is a house full of thirsty guests to satisfy. But maybe try leaving at least one bottle for a full 6 months – or even until the following Christmas, just to experience the difference. If you’ve ever tasted the devilishly sour fruits straight from the tree you’ll be amazed that such a pleasant flavour could possibly be lurking within them.

Brown Trout:

I often think of these as the freshwater equivalent of Mackerel: they are stunningly pretty fish; they snatch at any morsel of food in front of them, making them remarkably easy to catch; they are a doddle to cook and taste fantastic; and they can only be caught from spring to autumn (in this case the result of seasons set out in legislation rather than presence or absence). Across large parts of the Scottish Highlands and Islands (as well as parts of England and Wales) almost any freshwater you can find, deeper than a couple of metres, is likely to support them. A cheap fishing rod, float and hook with worm is all you need.

Of course, there is another kind of trout fishing, involving the same species, where things are very different. Along well-known trout rivers and the more esteemed trout lochs you will find well-dressed figures with expensive fly-fishing rods and even more expensive techniques who have paid handsomely for the privilege of trying to catch large specimen fish. In their eyes a worm isn’t bait, it’s cheating. They might also turn their noses up at the small size of some of the fish that I have taken home.

If you simply want to catch enough to eat that night (and you don’t necessarily want to spend the whole day fishing) then any technique that works is fine – why deliberately handicap yourself? And don’t feel guilty about taking small fish, as long as they are at least big enough to be worthwhile processing into food. My logic is that if I need 3lbs of fish then taking six half-pound individuals is probably no more detrimental to the population than taking a single 3lb fish. This approach also avoids having to put back lots of smaller fish that have been hooked in the hope that they will survive, whilst waiting for that elusive larger fish. To be fair, returning trout to the water is usually easy enough though this can be more of a problem with some sea fish.

I’m prepared to be shot down in flames by a fisheries scientist and some decent modelling but until then, taking a few of these home for tea is a near-perfect way to end a day in the Highlands.

Amethyst deceiver:

This is a very common species in the autumn and early winter in deciduous woodland, mostly under Beech trees in my part of the country. It provides an excellent example of the concept of ‘search image’ whereby things become much easier to find once you have got your eye in.

You wouldn’t think that vivid purple would be a good colour choice for blending into the background but, somehow, they manage it very well. And yet, in a good area, if you can find one or two, the brain learns how to pick them out. The seemingly bare forest floor gradually resolves into a faint purple haze and you realise you are surrounded by hundreds of them.

Its greatest asset is not its taste, though it is nice enough, but the amazing colour. It has a pleasingly-high shock value if served to guests that are not 100% committed to the wild fungi cause, giving lie to the unwritten, but almost universally-accepted, rule that a bright purple fungus cannot possibly be edible. Thankfully, they keep their colour when cooked.

Mentioning the name just as the meal is served helps add to the tension, though the second part is far more appropriate to its close cousin ‘The Deceiver’ which is also edible but so variable that it can indeed deceive the unwary. It’s rather hard to confuse the Amethyst Deceiver with anything else – though not impossible so, as always, do make absolutely sure before experimenting on your guests.

NOVEMBER

Beech Mast:

This is an abundant food source in years when the seed sets well, and it supports huge numbers of birds and mammals in Beech-dominated woodland. It’s true the seeds are small but it’s the numbers that are important. This year, locally, I’ve found a rough average of 30-40 per square metre under mature trees based on a few unscientific minutes of sampling. That works out at 30-40 million in just one square kilometre of forest. A quick literature search turned up figures as high as 800/m2 which is not far short of a billion nuts/km2. That’s a lot of bird food.

To be honest, they are not much use as food for humans because of their small size, the difficulty in finding them on a forest floor that is almost entirely beech-nut coloured and the fiddly process required to extract them from the shell. I can only include them here because I go through an annual ritual every autumn of finding at least a handful – just to remind myself of the taste (not bad but slightly bitter; nothing special) and as a way of finding out if it’s a good year. In some years almost all the shells are empty as the nuts have failed to develop properly and It’s easy to burn more calories trying to find a good one than you get back from eating it – though I see that as a good thing these days.

But in ‘mast’ years the forest floor is littered with them and I know it will be worth returning after the first spell of cold weather in the hope of finding flocks of Chaffinches and hopefully a few Bramblings. These years of abundance represent a communal attempt by the trees to outwit the multifarious hordes of seed raiders. Produce average numbers each year and they will be up to the task and consume the lot. But overwhelm them once in a while and they simply won’t be able to get through them all. It doesn’t need to work very often to be a very successful strategy in the life of a Beech tree.

The Blusher and friends:

One of the most fascinating aspects of wild fungi is the huge diversity of different substances they contain and the alarmingly varied effects of their consumption. This is well illustrated by this pair of very similar species in the notorious Amanita group. One will provide you with an excellent meal, the other may well be your last – or at least leave you suffering enough to wish it had been. The examples in the photographs were found at the same site in mid-Devon within 100m of each other this autumn.

They look very different here only because they are at different growth stages. The smaller, brighter individual (below) is a young Panther Cap, a stunningly attractive but highly poisonous fungus. The older specimen is The Blusher with a wider, flattened cap that has expanded from its more rounded younger form. It is an excellent edible species and also a very common one.

The features that separate these two at all stages of growth are rather subtle but distinctive nonetheless. One is the way that the white flesh of the edible species turns a weak reddish colour when exposed, the feature that gives it its name (and just visible in the photograph). Another, more clear-cut, difference is the series of vertical grooves on the loose white ring on the upper stem of The Blusher, not present in the Panther Cap. Incidentally, the joyfully (and aptly) named Death Cap and Destroying Angel are also close relatives though, thankfully, they look very different and so should not cause any confusion here.

Once you have safely identified and gathered your Blushers there is one final hurdle to overcome to ensure the day ends well. Even Blushers contain a toxin but, unlike those in the Panther Cap and its lethal relatives, it is rendered harmless during the cooking process.

Sweet Chestnuts:

This is not a native tree but it has been established in Britain for around 2,000 years and the nuts have long been exploited by humans. They only ripen well in some years and, even then, only on a sub-set of the mature trees. Climate change may help as the tree is native to warmer areas, including southern Europe and North Africa, though these nuts were found in Devon in mid-October after one of the most dismal summers for many years.

I can’t resist eating the nuts raw if I find them on a walk, though they have a slightly dry and bitter taste. It’s best to scrape away the fibrous coating after removing the glossy-brown outer shell or it can feel like trying to chew through a mouthful of fluff. If they are still in their cases then gloves (or a stout boot) will be needed to release them – the prickles have been superbly well-honed by evolution, making them almost impossible to handle.

Traditionally, of course, chestnuts are roasted over an open fire, with holes pricked into the shell to help the heating process and release the hot gas that otherwise builds up inside. It has been suggested (by Richard Mabey I think) that you can gauge when they are ready by leaving one or two with un-pricked shells. When these explode, the rest are ready to eat. In my experience, this rarely works perfectly, though it’s a great way of keeping children entertained, or a room full of drowsy Christmas visitors on their toes.

Hairy Bittercress:

For a small, low growing and rather unassuming plant, Hairy Bittercress has quite a bit going for it. It has the welcome habit of bringing wild food right to your back door as it often grows as a garden weed, springing up in flower pots, the gaps between paving slabs or around the edges of flower beds. It is available for most of the year, emerging in early spring and seeding itself right through into the winter if conditions remain mild, though it is often at its best earlier in the season.

It doesn’t entirely live up to its name in that it’s not especially hairy and it doesn’t taste bitter, though the cress part, at least, is spot on. You can use it in salads or in sandwiches and I find it a great fall-back for days when I haven’t been able to get out into the field; I can wander into the garden at lunchtime and brighten up a cheese sandwich with a sprinkling of leaves. I was delighted to find it last week in the grounds of my daughter’s accommodation at the University of Sheffield. She and her flatmates seem to subsist mainly on pizza but at least now they will be able to add a few bittercress leaves to top up their vitamin C levels.

The elongated seed pods (when present) are also edible, though the tiny seeds are eaten by small finches and other species, so leave some in place if you want to attract more birds to your garden. There are a few similar but less common bittercresses and the well-known Cuckooflower (or Lady’s Smock) is also part of the same group. All are edible and have varying degrees of spiciness so feel free to experiment.

Pollack and Coalfish:

I’ll admit to being more than a little surprised the first time one of these two species emerged from the sea when I was Mackerel fishing. Both are members of the cod family and they are often confused with each other. As with many apparently tricky species pairs, as soon as a direct, side by side, comparison is possible the differences become obvious. In this case, the shape of the lateral line that runs along the length of the body is a key feature. The upper fish with the line that turns sharply upwards about halfway along the body is the Pollock.

The huge eyes immediately suggest they are predators of other fish. The really large individuals tend to keep to deep water well offshore but these smaller (single portion-sized) examples were caught close in to the rocks, no doubt using them, and the abundant kelp, as cover from which to launch their ambush attacks on smaller fish.

They were caught in Sutherland in the north-west of Scotland within a few minutes of each other in late autumn. The fishing was enlivened by Sea Eagles flying across every so often, and a small group of Harbour Porpoises passed so close to the rocks that, in the calm conditions, I could hear the noise of the breath taken as they surfaced (apparently, they are known as ‘Puffing pigs’ in parts of North America, presumably because of this sound, as well as their small size).

Both Pollock and Coalfish are nice enough to eat and they are increasingly fished commercially as alternatives to the more familiar, and enduringly popular, Cod and Haddock. If you eat a lot of fish fingers then you’ve probably already tried them. Coalfish are marketed as ‘Coley’ and one supermarket tried rebranding Pollock as ‘Colin’ to make it sound more appealing to consumers. I’m not sure why that would work though I had an uncle with the same name so perhaps that’s why it sounds a bit odd to me.

DECEMBER

Porcelain Fungus:

It’s worth getting to know this spectacular species for several

reasons. It can grow in abundance on old Beech trees so, once found, you

are likely to have enough for a decent meal. It tends to persist into

the winter, even after the onset of cold weather has ended the season

for most other species. It has a nice strong flavour and is hard to

confuse with anything else which is always a reassuring feature in

fungi.

At a distance they really do look like they are made from porcelain; as

if a well-aimed hammer blow could send them crashing to the ground in a

blur of shattered fragments. Closer inspection reveals a different

truth. The caps are soft, flexible and literally dripping with slime.

The stems are drier and more fibrous and although that makes them

unpalatable, they do provide a welcome slime-free point of contact to

help the gathering process.

It’s best to remove as much of the slime as possible from the caps by rinsing, and then drying, them. They retain their somewhat slippery nature even when cooked, though the texture is not unpleasant to my mind. If you enjoy eating other fungi, these are worth trying at least once to see how you get on with them.

Primrose:

Hunting down things to eat (and write about) becomes more of a challenge as the winter months drag on, particularly during prolonged spells of cold weather. I certainly wasn’t expecting to find this species, at least not in flower, during the second half of December. Whilst it’s tempting to blame climate change for this sort of thing, the bitingly cold wind and patches of lying snow make that explanation feel rather inadequate.

In early spring primroses are a much more common sight, vying with celandines to add welcome splashes of yellow to woodlands and hedge-banks before the insidious, over-bearing daffodils start to take over. The name derives from ‘prima rosa’ meaning ‘first rose’, highlighting its early appearance and the rose-like flowers. Like the celandines, it must flower early in order to make the most of conditions before the trees come into leaf and shade the ground beneath.

To my mind it’s a bit of a stretch to call this food. I’ve never eaten it (and I wasn’t about to make an exception for perhaps the only flowering plant in mid-Devon at the time) but the petals can be added to salads or even used as a garnish for more savoury dishes. Combined with other edible spring flowers such as violets they would certainly add colour and interest to a meal if you could bring yourself to pick them.

Minke Whale:

I’ve had this argument a few times and I always seem to end up on the losing side. In starting to write this I have a sense, already, that I’m not going to influence many people. It’s such a contentious subject that the merits of logic and common sense seem not to apply in the usual way but, in the spirit of persistence (or hole digging), I’ll give it another go. To be clear at the outset, this is intended as a discussion of the issues around the rearing of domestic livestock rather than a suggestion that we should revive the UK’s whaling industry.

There are three main arguments used by those opposed to whaling. The first is that we are dealing with such highly intelligent animals that, as with the great apes, it is simply wrong for us to kill them. I can see how that argument might apply to the highly social dolphins and the toothed whales but I’m not sure it’s very convincing for baleen whales like the Minke. Assessing intelligence is notoriously difficult and, to some extent, subjective. Baleen whales do score highly but then so do pigs and other species that are killed and consumed with impunity. In some ways baleen whales mirror the behaviour of the terrestrial grazing animals that we are so fond of eating in the way they endlessly sift and strain tiny food items from the ocean.

Then there is the question of the level of cruelty involved in killing whales. It’s difficult to get to the truth of the matter and doubtless there is exaggeration on both sides of the argument. Clearly some suffering is involved so it’s a valid concern. But I’d be amazed if the overall levels of suffering per pound of flesh were not very much higher for the majority of domestic livestock, taking into account all elements of the production process, through to eventual slaughter.

Species that breed as slowly as whales are highly vulnerable to over-exploitation. It may be that for the largest species such as Fin and Blue Whales any level of exploitation would risk harming populations; killing them is not dissimilar to mining. But, for the smaller species, there will be a level at which they could be exploited sustainably even if that is a very low level. Of course, there are also very serious sustainability issues with the production of domestic livestock, including the destruction of vast areas of pristine wildlife habitat to accommodate them, or the crops required to feed them. Whilst there is at least room for rational debate about the sustainability of low-level whaling, the same does not apply to most livestock farming systems.

All of these points draw comparisons between whales and domestic livestock. If you are vegetarian they will be largely irrelevant. But based on concerns about animal welfare, sustainability and wildlife conservation I’m not sure it’s tenable to visit Burger King on a regular basis whilst maintaining a logically-based opposition to all forms of whaling. I would suggest that hamburgers seem more acceptable than whaleburgers only because our supermarkets and restaurants are full of them. We have got used to eating them and are well-practiced at turning a blind eye to the environmental consequences inherent in their production. As with many difficult issues, the human brain appears to automatically favour long-established practices over logical arguments.

There are some parallels with the contentious debate about kangaroo meat. This is available almost exclusively as a by-product of pest control in Australia. Some in that part of the world see it as one of the few sources of sustainable meat and there is even a new word, ‘kangatarian’ (I kid you not), for people who have given up meat for ethical reasons but make an exception for kangaroo. In contrast, Australian animal welfare groups object to it because it involves the culling of wild animal populations and is perceived as cruel. We end up with the bizarre situation where kangaroo is simultaneously regarded as the only ethical meat, and one worthy of vigorous (and sometimes successful) campaigns to stop it from being sold. In Britain we also have the option of meat from culled deer, with the added bonus to consumers that they are doing their bit to help limit the impacts of non-native species. Yet, there are many people who are very happy with their pork chops but would think twice before buying venison.

Hedgehog Fungus:

The feature that gives this fungus its name is both a godsend and a pain in the neck. The mass of spines on the underside, instead of the more usual gills or pores, make this otherwise rather nondescript species virtually impossible to confuse with anything else. So, if you are relatively new to foraging and wary of making mistakes, this is a good one to look out for. It is often found in deciduous woodland and can grow in the same places as the peerless Chanterelle, which is another good reason to keep an eye out for it.

Those spines though, once they have served their purpose in identification, do tend to cause problems. They are unbelievably brittle and splinter into hundreds of tiny pieces if you so much as look at them. They quickly litter your kitchen table and you’ll be finding them in unexpected places for days afterwards. I once tried to get around this by handling the caps with the utmost care until they were safely in the frying pan – which was a mistake. The spines survived the cooking process and turned an otherwise promising lunch into something akin to mouthfuls of dry gravel.

The best bet is to scrape the spines off in the woods as you gather them. It’s all a bit fiddly but once that’s done they taste very good indeed, though they do need to be well-cooked. They can often be found in large numbers, providing you with several days’ worth of mushrooms on toast in one picking.

According to John Wright’s unrivalled Mushrooms book in the River Cottage Handbook series, eating them may reduce chemicals in the body associated with tiredness. I’m not sure how good the evidence is for this but as a firm believer in the placebo effect it’s something that crosses my mind every time I eat them.

Puffballs:

There are a few different puffball species, ranging in size from the small, spiny, Common Puffball (the one in the photo) and its close relatives, to the altogether more impressive and aptly-named Giant Puffball. The stalks are often mostly hidden underground, though, as here, they can extend to several centimetres. The good news is that all the similar looking species are edible so the subtle differences between them aren’t worth worrying about – unless you enjoy worrying about such things. Do, though, watch out for the superficially similar earth-balls which have tougher, thicker, scaly skins and an off-white flesh, even when young.

The smaller puffballs are very common and whilst they are not the tastiest of wild fungi they are still more than a match for most shop-bought options. They are only good to eat when young, whilst the flesh inside is still pure white. As they mature and the spores ripen, the flesh dries out and starts to yellow, eventually reaching the final ‘puffing’ phase which gives them their name. These are the familiar brown papery structures that children (and adults) can’t resist stamping on to send a dark puff of spores shooting into the air. It might seem a bit mindless but it’s helping to secure the future of the species so don’t feel bad about it. If an accommodating human doesn’t find them, no doubt passing animals or even drops of rain are enough to do the job.

If you find a promising group of puffballs it’s worth cutting one open in the field just to check that it is still young enough to eat. That avoids the risk of harvesting a batch only to find, once you get home, that they are past their best. If you have the patience, it’s worth peeling off the outer skins before cooking as they are much tougher than the flesh inside and a little too chewy for the more discerning of palates.

And almost finally…

The benefits:

The comment below was made following a previous post in this series:

‘……. with 7.6 billion humans on the planet, ‘wild food’ is either unsustainable, or a tiny niche irrelevant to almost everyone.’

It got me thinking and although it’s hard to disagree with the overall sentiment, I do take issue with the last part. It’s certainly not irrelevant to me. I would argue that the benefits are considerable although they are easy to underestimate. They could become more relevant to a sizeable and meaningful minority of people in Britain (as is already true in other parts of the world) with little risk of compromising sustainability.

For me, the main benefit is tricky to define or quantify though is no less important for that. It relates to the greater connection it brings with the local landscape. There is something remarkably life-affirming about the act of gathering and eating things that you have tracked down for yourself in the local countryside. It’s hard to put into words but it presumably stems from the hunter/gatherer instinct that is there, somewhere, in all of us. For obvious reasons it’s an extremely powerful instinct though it can take some re-finding in our frenetically-busy and detached modern world. At its most malign it results in driven grouse shooting but it can be used for good things too.

This connection is similar to that resulting from watching (rather than eating) wildlife but it goes much deeper. You become more intensely aware of the gradual seasonal changes to habitats as different species rise in prominence and then fade from the scene for another year. A good autumn for Chanterelles is more memorable to me than, say, a good autumn for Red Admirals because it’s reinforced through the processes of searching, collecting and consuming. It’s hands on and it engages more of the senses – all of them in fact. It also pulls me back to the same places the following year, hoping for more of the same and helping me to appreciate year to year variations – and ponder the reasons behind them.

This connection is similar to that resulting from watching (rather than eating) wildlife but it goes much deeper. You become more intensely aware of the gradual seasonal changes to habitats as different species rise in prominence and then fade from the scene for another year. A good autumn for Chanterelles is more memorable to me than, say, a good autumn for Red Admirals because it’s reinforced through the processes of searching, collecting and consuming. It’s hands on and it engages more of the senses – all of them in fact. It also pulls me back to the same places the following year, hoping for more of the same and helping me to appreciate year to year variations – and ponder the reasons behind them.

There are other benefits too, that are simply not accessible by any other means – at any price. Much as people who grow their own veg struggle with the taste of shop bought produce, the same can be true with wild food. Try replicating the taste of a Brown Trout caught earlier that day or Parasols gathered in their prime from a local grassland and on the plate within an hour. A trip to the supermarket won’t help. You can’t buy the Parasols and whilst you might find the trout it certainly won’t taste as good.

There are other benefits too, that are simply not accessible by any other means – at any price. Much as people who grow their own veg struggle with the taste of shop bought produce, the same can be true with wild food. Try replicating the taste of a Brown Trout caught earlier that day or Parasols gathered in their prime from a local grassland and on the plate within an hour. A trip to the supermarket won’t help. You can’t buy the Parasols and whilst you might find the trout it certainly won’t taste as good.

There is a lot of wild food out there and a great deal more use could be made of it before there is any threat to its sustainability. It’s true that removing food from the countryside can have impacts on wildlife – some of them negative. After all, it is food for other things too. But for foraging to be a positive thing overall, the test is not whether there are no impacts, but whether the impacts are lower than the alternatives. These vary hugely but I’d be confident that local wild food comes out on the right side of the equation 99% of the time when compared with the closest supermarket equivalent. Anything gathered close to home or collected opportunistically when out and about doing other things has a food mileage of zero. In eating it, you are reducing consumption of shop-bought food with levels of sustainability that range from tolerable to ludicrous.

There is a lot of wild food out there and a great deal more use could be made of it before there is any threat to its sustainability. It’s true that removing food from the countryside can have impacts on wildlife – some of them negative. After all, it is food for other things too. But for foraging to be a positive thing overall, the test is not whether there are no impacts, but whether the impacts are lower than the alternatives. These vary hugely but I’d be confident that local wild food comes out on the right side of the equation 99% of the time when compared with the closest supermarket equivalent. Anything gathered close to home or collected opportunistically when out and about doing other things has a food mileage of zero. In eating it, you are reducing consumption of shop-bought food with levels of sustainability that range from tolerable to ludicrous.

Of course, as with any environmental cause (if that’s what this is), the actions of any one individual make only a tiny difference to the way the world works. But they do make a difference and if you can persuade a few others to join you that helps all the more. At the same time, you will be helping to increase the pool of staunch defenders of the local environment. Losing a place where you enjoy seeing Redwings and Fieldfares in the winter is one thing but if that same site provides what you need for your annual batch of sloe gin, its loss will be altogether more alarming.

Of course, as with any environmental cause (if that’s what this is), the actions of any one individual make only a tiny difference to the way the world works. But they do make a difference and if you can persuade a few others to join you that helps all the more. At the same time, you will be helping to increase the pool of staunch defenders of the local environment. Losing a place where you enjoy seeing Redwings and Fieldfares in the winter is one thing but if that same site provides what you need for your annual batch of sloe gin, its loss will be altogether more alarming.

I was very taken by something George Monbiot wrote recently about the benefits of trying to act positively rather than giving up in despair (in respect of climate change but the same applies here). Why should individuals even bother trying to minimise their impacts when global behaviour patterns mean we will inevitably lose much of what we hold dear? Well, if all we can do is help to ‘draw out the losses over as long a period as possible, in order to allow our children and grandchildren to experience something of the wonder and delight in the natural world……….. Is that not a worthy aim, even if there were no other?’

Wild food can help with that, in a small, but nevertheless worthwhile, way.

And finally…

Useful books:

These are a few of the books I refer to most often or have found especially inspiring. Mainly they are about the essential business of identification but they also describe how to go about tracking down edible species and what you can do with them once you have found them.

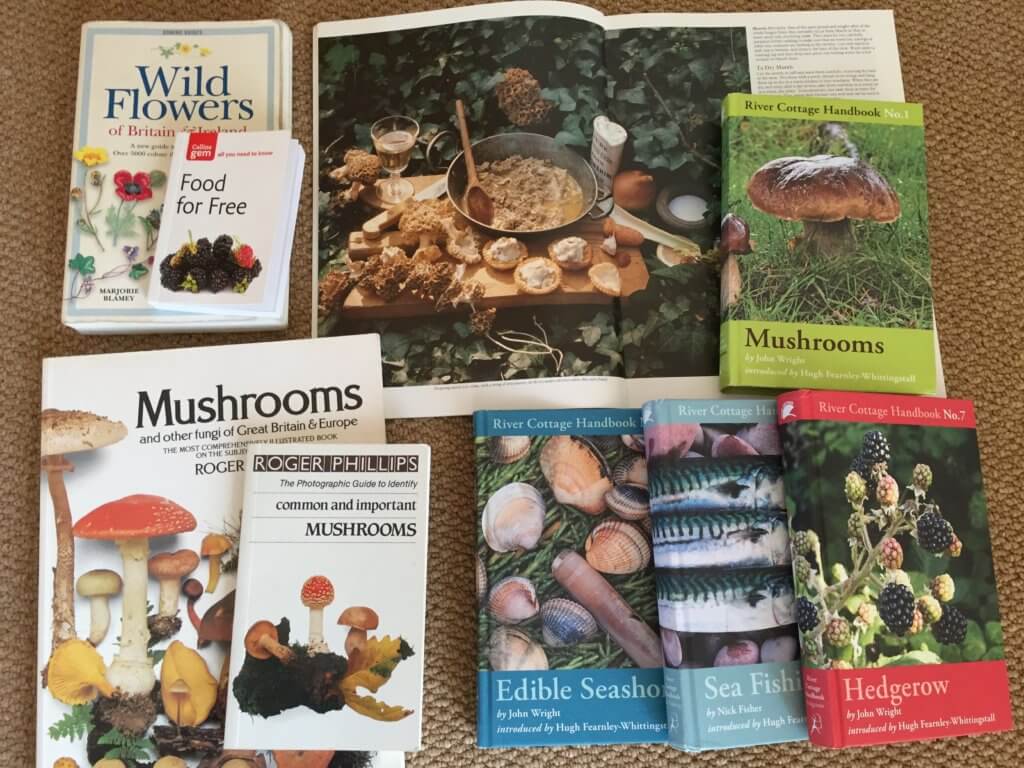

There are four books in the excellent River Cottage Handbook series that I can’t recommend highly enough. They are Mushrooms, Hedgerow, Edible Seashore, and Sea Fishing, the first three all by the same prolific author, John Wright. Together they cover the great majority of useful wild foods. They are full of detailed information (and excellent photographs), but are also thoroughly entertaining. I value the way they lend a sense of normalcy to the whole process because the authors come across as intelligent and down to earth, but also have a sense of humour. In the modern world leaping into a ditch to peer at fungi emerging from the leaf litter can be seen as rather odd. Reading these books helps you to realise that, on the contrary, it all makes very good sense.

Roger Phillips has produced many excellent large-format photographic guides over the years, mostly involving wild and domestic plants. There are two I use frequently – Wild Food and Mushrooms, first published back in the early 1980s. Wild food has lavish, full-page images of meals prepared from wild ingredients that are guaranteed to make you feel hungry and help get you out of the house. I also use his slimline photographic guide to Common and Important Mushrooms which is handy for taking into the field. In this context ‘important’ tends to mean the ones that are nice to eat and the ones that might kill you.

Richard Mabey’s classic Food for Free was (amazingly) first published almost 50 years ago and was in large part responsible for the surge of interest in wild plants and fungi as a food source. By the 2003 edition he felt able to say in the preface that ‘the subject has lost the slight note of eccentricity it once had……’ and that foraging has ‘become an acceptable family pastime again’. The tiny Collins-gem edition I have weighs less than the iphone I use to take the blog photos and packs in an incredible amount of information including artwork and photographs. The illustrations are so small that they are not always definitive but it’s still a great book to have in the field. It can help you decide if something is worth taking a chance on so that its identification can be confirmed once you are back at home. To that end it’s useful to have a comprehensive field guide for plants and there are many high-quality options out there. The one I tend to use most is Wild Flowers of Britain & Ireland by Blamey, Fitter & Fitter.

These days a huge amount of information is available online. It pains me to admit it but often I can get the information I need more quickly by typing a few words into a search box than by trying to work out if I’ve got the relevant book, and if so, what I’ve done with it. I find it particularly useful to be able to search for images of a particular species just to help confirm an identification. For the more common species there are huge numbers of images available, in contrast to the necessarily limited selection presented in field guides. Species can sometimes be mislabelled online but if you do enough searches you will come to trust certain sites as reliable sources of information.

In true Desert Island Discs tradition, if I was recommending just one source of information for anyone starting out it would be Mabey’s Food for Free. It has an inspiring introduction to the subject that sets modern foraging in context with the long history of human exploitation of plants in Britain. It is available in various editions and formats but the mini-version takes up almost no space at all in your coat pocket and you can find it online for less than the price of a pint. By the end of your first walk you may well have found enough to have made your money back.