I liked this book.

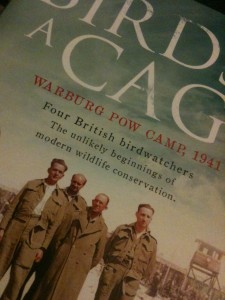

Birds in a Cage is the story of four British prisoners of war, Second Lieutenant Peter Conder, Second Lieutenant John Buxton, Second Lieutenant George Waterston and Squadron Leader John Barrett, who, after WWII, went on to influence nature conservation practice and policy.

Birds in a Cage is the story of four British prisoners of war, Second Lieutenant Peter Conder, Second Lieutenant John Buxton, Second Lieutenant George Waterston and Squadron Leader John Barrett, who, after WWII, went on to influence nature conservation practice and policy.

It’s a remarkable tale which is beautifully told. On the face of it, it might not sound like the most interesting of subjects, but it really is fascinating.

Reading this book made me think of how easy birders have it these days with great optics. and field guides, and recordings of songs, and distribution atlases etc. And it made me think about how important nature was to these men and how their love of nature helped them endure hardships that were extreme. Walking, exhausted, through a frozen landscape these were the type of folk to keep a bird list as they travelled.

And I wonder how the birds have changed in numbers in the last 70 years. Are the skylark flocks flying still over Warburg (North Rhine-Westphalia) in mid-March in numbers of up to 15,000 a day? I wonder.

I wonder too whether any similar records were kept by German or Italian PoWs in the UK? Prompted by reading this book I discover that there was a PoW camp just up the hill from my local birding patch – I wonder whether there were any captive ornithologists there.

The story is interesting and the writing is excellent. For example, the opening sentence to the second chapter is surprisingly funny.

The strong message from this book is that the existence of nature was incredibly important to these men – as was studying the natural world around them. A little thing like captivity during a World War wasn’t going to deflect them from their passion – indeed, in some ways it gave them the time and opportunity, and by chance the companions, to study more, learn more and think more. If you feel imprisoned in any way by your life then there may be a lesson for you in this book. There certainly is a message of hope and human endurance written through this excellent book.

[registration_form]

Mark, thanks for highlighting this and congratulations to Derek Niemann too. Whilst meeting with Peter Conder , many years ago, when he was helping me with some arrangements in Jordan, he briefly mentioned the time whilst we were discussing shrike migration. It struck me then how significant birds and nature had been , for some, in their period of captivity.

Equally I remember a hard-bitten old collier in South Yorkshire recounting his own experiences in the First World War and how the beauty of bird song uplifted the troops on occasion.

I shall take great pleasure now in having a good read!! John.

Stephen Moss makes a brief mention of this in his book ‘A Bird in the Bush – a social history of birdwatching’, where he also notes birds in the poetry of Siegfied Sassoon during WWI. Sounds like Derek Niemann’s book is well worth a look.

As a flippant aside, birdwatching also gets a mention in ‘The Great Escape’! The Donald Pleasance character ‘Blythe the Forger’ is a birder and, at one point, is seen explaining the identification of masked shrike to a group of POWs.

Andrew – yes, I remember that. It always jars slightly with me. If they had chosen great grey, woodchat, red-backed or lesser grey then it wouldn’t!

It sounds an interesting read can I highlight a few more examples, the first one (names are vaery vague) was about some of the prisoners of Colditz and they read out a passage of one prisoner whom would write about a Common Redstart. Then there was an article on Birdguides “BIrding in a war zone” about a war reporter/photographer (can’t remember the paper) who talked about his time in Somalia/Afghanistan and Libya. The last, Libya I remember as I saw an image of Terns he posted on the gallery in Bengazhi and thinking “who would risk taking photo’s in such a dodgy situation”. And finally on BBC 3 there was a doucmentary series called “Our Boys”, and featured a high ranking squaddie who whilst on patrol would take a field guide out with him and birdwatch, though funnily there was one bit when a squadie told him about a particular bird and he was frustrated as he couldn’t find it out on patrol, it was a stringer

I have the original book here, inherited from my father who collected all the early New Naturalists: Monograph number 2, published 1950, by John Buxton ‘The Redstart’. It is based around 850 hours observation he and his companions carried out in their POW camp in April, may & June 1943. An amazing story.

I did have the privilege to meet John Buxton a couple of times. A gentleman who was happy to discuss birds at your level without making it obvious he knew heck of a lot more than you did.