I very much enjoyed David Cobham’s previous book on raptors, A Sparrowhawk’s Lament. This new, slim offering has many of the same features that made that book such a pleasure to read; a love of raptors, a selection of anecdotes and a range of snippets of conversations with others involved in the subject. But this book as the title signals, is not just about one species of bird, the Hen Harrier, but takes as its entry point one individual of that species, a Hen Harrier that was hatched in the former stronghold of the Hen Harrier in England and which was shot on a grouse moor in the Yorkshire Dales National Park before she had the chance to nest and rear her own young.

First the name – birds don’t really have names but this one, named by volunteers in Bowland, was known as Bowland Betty after Bet Lynch, barmaid of Coronation Street fame, but Cobham prefers Bowland Beth. The very idea of identifying wild birds by given names is an interesting one. With our use of modern technology allowing us to follow the movements, ups and downs, and eventual fate of individual birds, often almost as they happen, then we want to talk about these individuals as individuals. Their ring numbers or tag numbers seem very impersonal and so we give them names. And these names make us feel closer to the birds too. The news that ‘Betty’ has died is rather more emotive than that 834759 has died.

And this book takes us into the short life of this ill-fated Hen Harrier as a way of describing the species, its habitat, its way of life and the all-too-frequent manner of death. Bowland Betty joins the list of Tarka the Otter (which David Cobham produced), Sammy the Stilt, Elsa the Lioness, and other named animals of repute.

Does this approach work? Yes, it does. In some ways there isn’t much to say about such a brief life but Cobham’s writing is up to the task. If you have seen Hen Harriers then the tale of this single bird will take you back to your sightings and perhaps make you wonder about what the bird was doing, and where it had travelled before you saw it, and what happened to it afterwards. As with all species, including our own, the headlines of a species’s fate, its birth rate and death rate, are made up of the successes and failures of individual birds. And this book brings that home. And if you haven’t seen a Hen Harrier then this book will introduce you to the bird in an engaging manner.

In her short life Bowland Betty travelled from Lancashire to many parts of Scotland and often to the other side of the Pennines. Those travels are told particularly well and she spent much of her time in National Parks and AONBs. She died, she was shot, in perhaps our most notorious National Park for wildlife crime – the Yorkshre Dales. But if it hadn’t been there then it might have been in the Peak District or the North York Moors.

The book is beautifully illustrated by Dan Powell. His line drawings are evocative and captivating. They are a real asset.

I do, however, have a few niggles with the book.

The publisher has mucked up the indents, punctuation and line spaces in quotes from other works in a few places: it’s only when these things aren’t done right that you notice them at all. There are a fair few typing errors, but I have sympathy with those, as an author I am poor at spotting them because I tend to read what I think I wrote rather than what is on the page – but someone should have spotted them. And no-one is acknowledged for having read through the manuscript and checked the facts – there are a few things that should have been weeded out eg the Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty designation is nothing to do with the EU, it’s all ours but perhaps the author was thinking of Special Protection Areas which don’t get the mention they might.

There is quite a lot of geographic specificity when it comes to the locations used by Hen Harriers and Eagle Owls in Bowland. The Forest of Bowland is a big place, but very specific real locations are named here. I suppose that since we believe that the threats to the birds come from locals rather than outsiders, this doesn’t increase the risk to birds much, but I’d have thought that using made up names might have been wiser.

Cobham gets much of his detailed information from Stephen Murphy of Natural England who has been studying Hen Harriers for many years, first with radio tags and then with satellite tags, and who tagged Bowland Betty originally, and found her body in Yorkshire. This book is dedicated to Murphy with the suggestion that he ‘guards the flame that keeps alive the future of our English Hen Harriers’. Is that really fair to others working on the species, and is it an accurate description of NE’s role in the Hen Harrier’s decline? Natural England has been pretty useless in recent years and Murphy is hardly running the show.

My main disappointment with this book is that it fails, quite badly, to put the plight of this individual bird, or the species as a whole, into its proper policy or science framework, although it scatters snippets of the story through the text without enough explanation or synthesis (for me). There is no list of references or further reading and it is almost as though the author has relied on the thoughts of a few mates to form his view of the subject. For example, we learn little about the impact of Hen Harriers on the potential bags of Red Grouse on shooting estates which is at the very root of the reason why Hen Harriers are killed by grouse-shooting interests. There is no mention of the results of the first Langholm study (1992-96) which was a pivotal event in our understanding of the conflict between this magnificent bird and grouse shooters. In fact, we are told, erroneously (page 93), that ‘Hen Harriers do not commonly kill red grouse’. This might leave grouse moor owners gasping!

Cobham states that diversionary feeding of Hen Harriers (providing food at their nests so that they don’t go and eat Red Grouse) is not popular with many conservationists but it actually forms one of the least contentious parts of a Defra plan ‘for’ the Hen Harrier and the real problem with diversionary feeding is landowner indifference to it, and a preference for removing Hen Harriers from their moors rather than feeding them when they arrive.

One might have hoped to learn more about the highly contentious brood management scheme considering that Cobham has been, until last week, a long-term trustee and then vice-President of the Hawk and Owl Trust, whose current chair, Philip Merricks, has been its most enthusiastic proponent. It is briefly mentioned (page 174) and then explained (pp190-92) with the revelation that a five-year trial is funded (is it?), but Cobham remains tight-lipped about whether he supports it or not. The best words on the subject are spoken by one of the two Bowland Bills, Bill Hesketh, but his pithy verdict on the scheme come much earlier in the book than the explanation of what the scheme actually is.

Throughout, the author gives little away as to what he thinks is the solution to the conflict between grouse shooting and Hen Harrier conservation. The issues aren’t really tackled and the difficulties aren’t really explained. There’s no doubt that Cobham wishes people would stop killing these birds illegally but he isn’t clear about how this might come about and I find that a shame, as I was looking forward to finding out. There are no conversations with the game community that allow them to express their views.

For those new to the Hen Harrier then I hope this book will introduce them to a marvellous bird – the tales of harriers and harrier workers are the most engaging parts of the book. If it introduces more people to the plight of the Hen Harrier then it will have done a wonderful job. For those who already know the Hen Harrier, and are engaged in its plight, this book will provide much of interest and value. What they won’t find here is any road map out of the current predicament.

Bowland Beth by David Cobham will be published by William Collins on 10 August.

Last week I reviewed Donald Watson’s classic book, reissued as a second edition: The Hen Harrier.

Next week, I review another rather different book which is also much engaged with Hen Harriers.

Inglorious: conflict in the uplands by Mark Avery is published by Bloomsbury – for reviews see here. ‘A powerful indictment of the grouse-shooting industry and its illegal shooting and propaganda war against the Hen Harrier‘ – The Guardian

And if you are engaged with the plight of the Hen Harrier then come to a Hen Harrier Day rally on 5 or 6 August – here is a list of venues across England, Scotland and Northern Ireland.

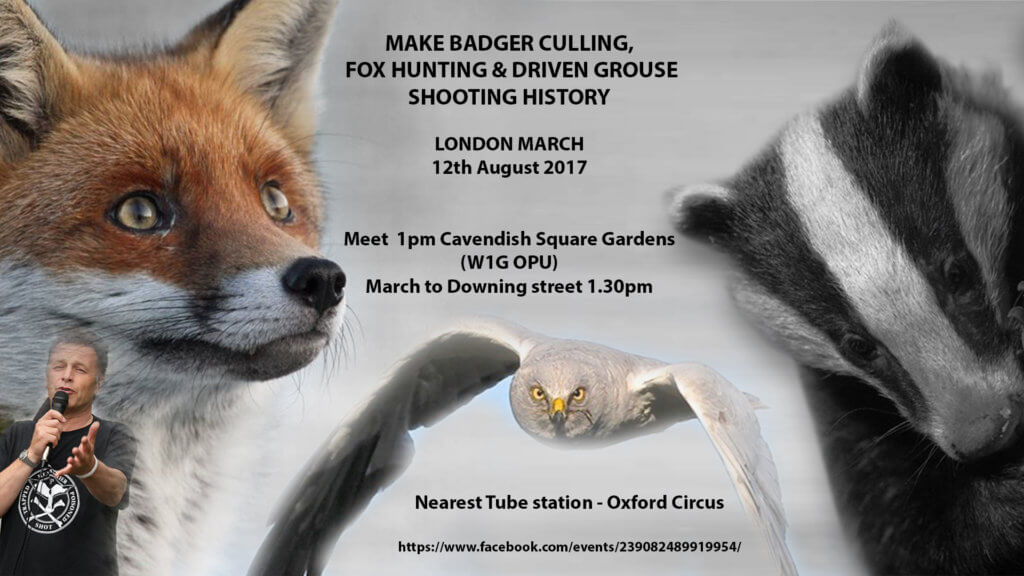

And then there is this event in London on the Inglorious 12th.

[registration_form]

Of course I have not read this book yet but if [like you say] it gives reference and dedication to one man who is paid by Natural England not the dedicated field workers who have spent their lives working in their own time and at great expense trying to save the Hen Harrier then may be the book has taken the place of a volume which could have actually done the job far better.

I know an idiot who is trying to do a Short eared Owl book by sitting in his car and the occasional bird hide but does not listen to folk who have studied the bird. Are publishers that naive? I know a Snowy Owl book was done in high profile but missed out the main worker with years of experience mainly as he had yet to finalise his papers! I know folk out there must know many more examples but when the wrong book is written then what chance any one else as the publishing world seems to be who you know rather than what you know !

Betty who I spent a whole winter in Yorkshire trying to catch up with as she lived a charmed life in some of our worst raptor killing estates did not die in the Yorkshire Dales National Park, she died on Thorney Grain Moor belonging to the notorious Swinton Estate in the Nidderdale AONB. I will almost certainly buy the book as a self confessed ” harrier nut.” Doubtless I will find similar fault to Mark but this is a book we should encourage lots of folk to read so they have a true understanding of what English or for that matter Scottish grouse moor harriers are up against.

Paul – thanks.

I have just read this book. Not being from the northern hemisphere, I know nothing of the hen harrier, and little of the environmental issues in the UK, but I found the book informative and engaging. It had faults and I recognised them as I read it, but it also made me want to learn more. A book does not have to be the definitive source to be worth publishing or reading.