Claire Wordley works on the Conservation Evidence project, with an emphasis on getting people to use the available science in conservation – and to test their own conservation interventions. Say hi at @ConservEvidence

Claire Wordley works on the Conservation Evidence project, with an emphasis on getting people to use the available science in conservation – and to test their own conservation interventions. Say hi at @ConservEvidence

Evidence, Experts and Effectiveness in Conservation.

Evidence in conservation covers a multitude of possibilities. A beautifully produced map showing species hotspots. The blip on a computer screen showing that the DNA of a dangerous disease such as chytrid is present in an animal. The statement made in court that a development project will destroy a rare ecosystem. The body of a poisoned bird of prey.

The Conservation Evidence Project, which today launches the third edition of its flagship book ‘What Works in Conservation’, gathers evidence in the form of tests of conservation interventions. Testing interventions means looking at what has been done in the name of conservation – adding wildflower strips down the side of a meadow, putting streamers on the back of fishing boats to scare birds, or educating people about the value of birds – and saying, well, did it work? This is important, as we will not save nature with good intentions alone. There are times when conservation projects (and other well-meaning projects) got it wrong – I explore a few examples from scary prisons to bridges for bats here.

‘What Works’ is free to download (though can be bought in paper form too) and aims to summarise the evidence for what works – and what doesn’t – across a range of conservation problems. Aiming eventually to cover all taxa and all habitats globally, the 2018 edition of ‘What Works’ consists of twelve chapters covering a range of taxa (amphibians, bats, birds, primates), habitats (forests, peatlands, shrublands and heathlands), and topics (European farmland conservation, soil fertility, natural pest control, management of captive animals, freshwater invasives) of interest to conservationists.

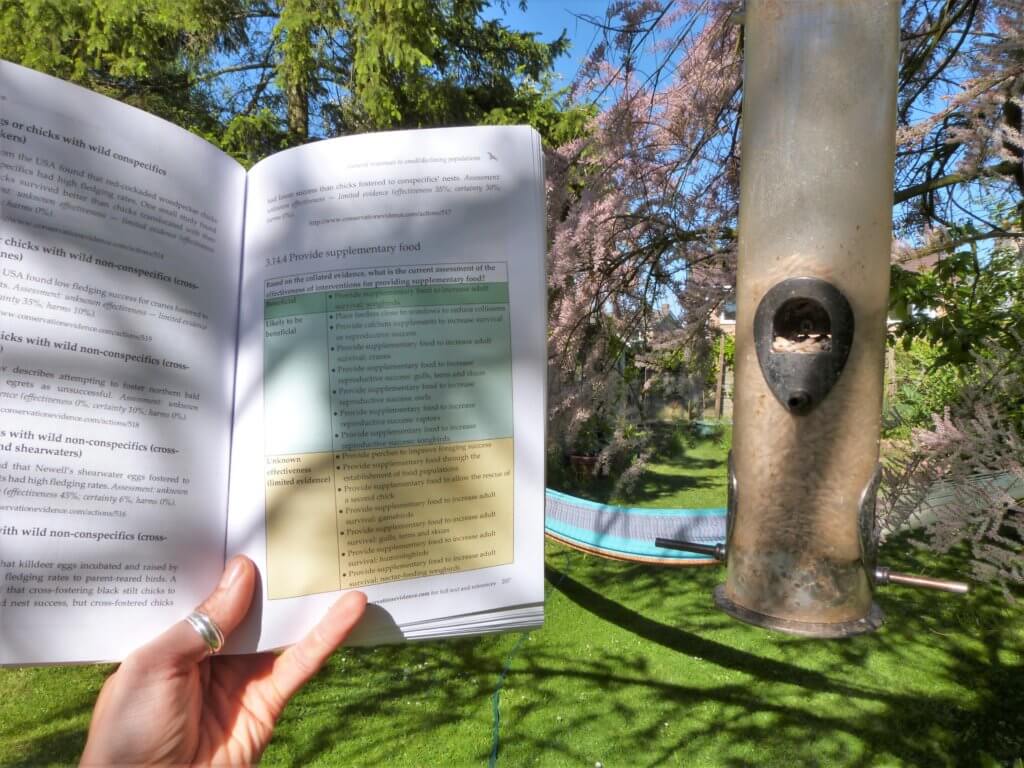

For each chapter the authors take the possible conservation actions you could take to address the key issues, and search for any tests of these actions. The data are gathered, summarised and assessed by experts on each topic (drawn from both scientific research and conservation practice), who look at how effective each action is, how certain we can be in the current evidence base, and any harms that arise to the target taxa or habitat. These scores are combined to assign each intervention an effectiveness category such as ‘Beneficial’ or ‘Likely to be ineffective or harmful’ (see sample page). The experts take part in two rounds of anonymous scoring for each intervention, to try and even out biases and reduce the impacts of people following the scores of the most prestigious individuals.

A sample page from the bird chapter of ‘What Works in Conservation 2018’.

Of course, this is highly condensed, summarised information – to find out more detail for a given action, you can follow the link provided for each intervention. This will give the breakdown of where and how all studies were conducted, and exactly what the results were. As the project grows, the aim is to update each chapter every couple of years, as well as adding new chapters by summarising the evidence for more taxa and habitats. The first updates – on bats and birds – are currently underway, likely to be included in the 2019 and 2020 editions respectively.

If you think that this sort of evidence is useful in conservation (and I really hope that you do), there are several things that you can do to support this project. As a researcher, you can get out there and test more interventions. A 2005 study from three top conservation journals showed that fewer than 13% of papers were tests or reviews of conservation interventions. Each chapter of ‘What Works’ highlights glaring evidence gaps where either no knowledge exists, or the evidence is so sparse or inconclusive that the intervention is classed as ‘Unknown Effectiveness’. Round up your lab group and point them at these problems – a lot of the knowledge gaps would make fantastic Masters/ PhD theses, and all of them would solidly tick the ‘impact’ box at REF.

Conservation practitioners (I sort of hate that term, but it’s a useful catch all for reserves managers, conservation officers, ecological consultants, NGO CEOs, etc): use the evidence that is out there. Of course, you’ll want to use the evidence most relevant for you, and combine it with your personal experience and what you care about – that’s great. But don’t ignore all science other than studies done in your exact circumstances – taking a broader view can be illuminating. Try to test the conservation work that you do, where possible – bite off discrete chunks that you can implement in such a way as can be experimentally tested. Call some academics in, if necessary. And remember that you can publish suitable results for free at the Conservation Evidence journal.

We believe that that the 2018 edition of ‘What Works in Conservation’ is a useful resource for a wide range of conservation professionals. It is our aim that this book and website will help to make conservation decisions that are better informed by evidence; and, hopefully, therefore more effective at saving the incredible richness of life that clings stubbornly to this beautiful planet.

Thank you Claire. Resources for conservation are limited and we cannot afford to use them on interventions that are ineffective, still less on things that may actually be harmful so this work is extremely valuable.

One area it would be interesting and potentially useful to investigate is whether measures targeted at a single species (or a restricted group of species) may be harmful to other taxa and if so how the overall impact an be evaluated.

Thank you! This is a really important point and one that we are still grappling with how best to address.

The way we currently gather evidence is by synopsis (each ‘chapter’ in What Works), usually dealing with a taxon (e.g. birds) or habitat (e.g. forests), which is then assessed for effectiveness, certainty and harms as regards *that* taxon/habitat (not others). This is because we currently get funding to work on one taxon/habitat at a time.

As we cover more and more taxa and habitats we want to try and link all of the similar actions together, so that people can see for all taxa/habitat what the benefits and harms are. Our first step towards this is developing a taxonomy of interventions so that they all have matching names in the different chapters – this is work in progress.

The best we can do at the moment is that if you look at an action, search the key word or words from that action across the whole conservation evidence website, so you can look at the impacts on other taxa. But of course, we are limited by the data that are made available, which almost certainly under-represent harms.

More info can be found here: https://www.conservationevidence.com/faq/index and https://www.conservationevidence.com/content/page/89. I hope this makes sense!

Yes! Thank you Claire.

I think this is a fantastic initiative and potentially extremely useful. The amount of work that has gone into it is incredible.

I do wonder how the project managers have handled grumpy responses from people who disagree with one or more specific assessments of effectiveness. Maybe this is mentioned somewhere on the website. If those grumpy people are vociferous and or influential this might in some cases generate more heat than light.

Sorry for the delayed response Dave. Of course we get some grumpy responses every now and then, but we try to see if we can learn anything from them or if they are just upset that one of their top projects did not score well with us! Thick skin and a smile. We get far more positive responses than negative.

In terms of the expert scoring, we take great pains to stop one or two voices from dominating. The scoring is anonymous so influential people have no extra sway, and occurs over two rounds, maybe three if it takes a while to reach consensus, until all experts are reasonably satisfied with the score.

See more under ‘how is the evidence assessed’ here. https://www.conservationevidence.com/faq/index