Alick Simmons is a veterinarian, naturalist and photographer. After a period in private practice, he followed a 35-year career as a Government veterinarian, latterly as the UK Government’s Deputy Chief Veterinary Officer. Alick’s lifelong passion is wildlife; he volunteers for the RSPB and NE in Somerset, is chair of the Universities Federation for Animal Welfare, a member of the Wild Animal Welfare Committee and a trustee of Dorset Wildlife Trust. A particular interest of his is the ethics of wildlife management and welfare. He is pictured above on the People’s Walk for Wildlfie inSeptember 2018 (Photo: Stuart Reeves).

‘The Wild Animal Welfare Committee holds its second conference in Edinburgh on 27 March. The theme of the conference is ‘Who are the guardians of wild animal welfare?’ This article forms the basis of a presentation to be given at the conference to be followed by an open discussion. The conference will be of interest those involved in the conservation and welfare of wild animals and is open to all. Booking details.

Introduction

For over a hundred years, the welfare of livestock, companion animals and research animals has been protected by legislation, codes of practice and associated efforts to ensure compliance. While few would argue these measures are perfect, a duty of care is well-established. Science has driven change in recent years but improvements in conditions have also been driven by ethical considerations; the general public’s dislike of caged chickens preceded the science that demonstrated the stress caused by the thwarting of normal behaviour.

The welfare of wild animals, in contrast, has had little attention. However, there is every reason to apply considerations of ethics and science to the welfare of wild animals. Importantly, ethical considerations need to include the ‘Why’ as well as the ‘How’.

Most factors affecting the welfare of wild animals such as predation and disease are outside of the direct control of humans. These are not the subject of this article. However, human activity affects the welfare of wild animals, by acting on the individual or on whole populations, and includes the following activities:

- causing death, injury, disease or starvation

- removal from home range/habitat

- social group disruption and disturbance

- the consequences of hunting, shooting and wildlife management (including so-called ‘pest’ control)

- wildlife trade and entertainment

- wildlife research

- wildlife rescue and rehabilitation (including releases and re-introductions)

- agriculture

- conservation

- the consequences of the built environment e.g., roads, buildings, wind turbines, etc.

It is neither practical nor desirable to influence the welfare of wild animals in all circumstances. Free-living wild animals will suffer and die, and it is generally inappropriate to interfere with the natural course of events. In parallel with conservationists’ efforts to ensure abundance and diversity, we need to consider how anthropogenic activities affect the welfare of wildlife. There are a number of reasons for this:

- The increasing evidence of sentience in a growing number of species.

- The level of protection afforded free-living wild animals is patchy and inconsistent. Many activities that affect wildlife, from sport shooting to so-called ‘pest’ and predator control, have carried on largely unquestioned for decades, either because the practices were unknown or unobserved, or simply because they have always been done that way. Much practice and legislation which covers wildlife ‘management’ is based on tradition, is out of date and is not supported by available evidence.

- There is little evidence that the most widely-used traps kill animals humanely even when used in accordance with best practice. Various types of spring trap were ‘approved’ historically with no recorded evidence that they cause instantaneous and irreversible loss of consciousness. Unregulated traps (e.g. mole traps, breakback traps) are freely available: There is no evidence that they meet the 5 minutes to irreversible unconsciousness threshold currently used in UK for trap approval. Few trap types require regular inspection.

- General Licences to kill certain species seem to be issued simply because it is traditional to shoot e.g. carrion crows Corvus corone. How landowners are held to account for meeting the conditions of the licence is unclear.

- The process of issuing Specific Licences to take or kill otherwise protected species is opaque; the rationale for their issue is not made available and individuals and organisations appear rarely to be held to account.

- Inconsistencies in the way in which wildlife is valued deserves closer scrutiny. For example, the brown rat Rattus norvegicus is a social and intelligent animal but the care given to the pet rat and in the highly regulated environment of animal-based research contrasts sharply with their treatment in the wild.

- The need to take account of the welfare of those ‘left behind’ when social groups are disrupted by the killing or taking of wildlife.

- Welfare impacts from changes to the built environment. Novel developments may affect the environment and create new hazards for the wildlife living in or nearby, for example, innovative and larger buildings, more extensive transport links and changing land use patterns.

- Welfare impacts of wildlife research and conservation. The activities of scientists and conservation bodies have the potential to adversely affect welfare; wildlife rehabilitation, identification tagging, research, translocation and other conservation-related activities have consequences for the welfare of the individual, which are sometimes overlooked or unanticipated.

There has been some success in securing protection for wildlife. Backed by science, the introduction of controls over pesticides and the prohibition of the use of gin traps, and of strychnine were major achievements. The Animal Welfare Act 2006 introduced a duty of care to animals under the control of humans and this is believed to apply to wild animals held captive e.g. held in a trap although this has not been strengthened by detailed requirements.

Current Guardians

Who, then, are the current guardians of the welfare of wild animals? Insofar as this is recognised and addressed, either in legal protection or practice, guardianship appears to be in the hands of a few individuals and organisations. Decision making is poorly governed, unaccountable and opaque. This sentiment applies equally to some regulators and conservation NGOs and although it is clear that some bodies have sought to apply an ethical approach there is scant evidence of wider engagement or a co-ordinated approach. The citizenry (and conservation NGO members) are, to all intents, excluded.

The Case for an Ethical Framework

There is a strong case for better governance of human activities where these affect the welfare of wild animals. The keepers of farm, companion, zoo, research and other captive animals in the UK are subject to animal welfare laws which, while having a basis in science, have also been shaped by ethical debate amongst parliamentarians and the general public. An approach which combines science and ethics to reduce harm to wild animals and prevent suffering caused by human activity is warranted.

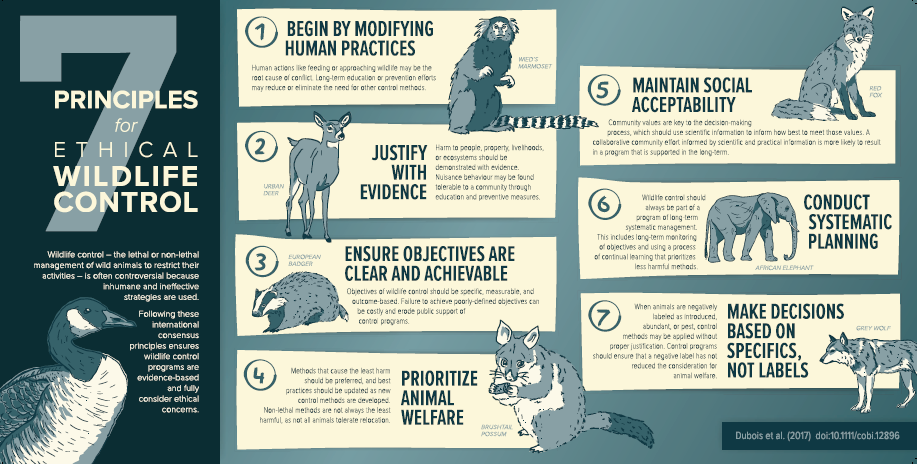

An ethical framework governing the full range of human intervention on wild animals would increase accountability. A requirement for an evidence base would ensure that decisions to kill wild animals using traps, poisons and other methods of capture and killing would be open to challenge and scrutiny. An example of such a framework is below.

In essence, any human activity that requires the systematic and sustained killing or other intervention which threatens wild animal welfare without an evidence base to support it would be deemed unethical. This does not preclude all intervention. It would be incumbent on the proponents of intervention to present rigorous cost-benefit analysis of the alternative interventions which take account of the social value of the species in question. The aim is to adopt the least intervention and avoid killing predators and other wildlife with few exemptions.

An ethical framework (e.g. Dubois et al. 2017) should be adopted by all those making decisions about wildlife including landowners, conservation organisations. A modified approach which takes into account considerations of harm and benefit is likely to be helpful for introductions, research, ringing and tagging, etc. A similar approach may be equally valuable when considering changes to the built environment.

Adopting an ethical framework with transparent governance would require considerable changes in attitudes and practice. Ensuring compliance may require independent oversight. Attitudes in certain communities would need to change considerably, particularly in quarters not used to scrutiny of their activities.

A consistent approach for all species where killing is considered creates a challenge for us all and not simply the occupants of large tracts of land. The killing of rodents, which is routinely practised in domestic households and business premises and which takes little account of welfare and environmental impact, would be subject to the same framework.

Human intervention against wildlife, regardless of the rationale and the evidence base, should never be open-ended; an exit strategy is essential. Otherwise, it is simply a form of game-keeping.

Such an approach may need to be supported by legislation to be effective. Experience suggests that better protection is rarely achieved without legislation, but attitudes need to change in addition and a wide-ranging debate is required before change can be effected. Legislation and other controls might be avoided if conservation bodies and other NGOs, landowners and their representative bodies, etc opened decision making to greater scrutiny. By way of example, all animal research establishments are obliged to convene an animal ethics committee which scrutinises all proposals. An empowered committee for local or national decisions about wild animal welfare would be a major step forward particularly if this involved lay people and greater transparency.

Future Guardians

Who, then, are the future guardians of wild animal welfare? Many of us value, support and strive for an abundant and diverse wildlife. We may not own land but that should not exclude us from decision making. Processes which involve an evidence base and cost-benefit analysis offer the opportunity to better decision making. Shining a light on proposed interventions would ensure the adoption of best practice rather than adherence to tradition. Further, it provides the means to involve others with an interest in the outcome not simply those with a traditional or financial interest. In essence, the future guardians can be whoever we choose them to be but, given the increasing interest and involvement of the general public in the environment, a sustainable solution must give greater voice to the citizen whether or not they have a financial interest in the outcome.

Reference:

Dubois, S. , Fenwick, N. , Ryan, E. A., Baker, L. , Baker, S. E., Beausoleil, N. J., Carter, S. , Cartwright, B. , Costa, F. , Draper, C. , Griffin, J. , Grogan, A. , Howald, G. , Jones, B. , Littin, K. E., Lombard, A. T., Mellor, D. J., Ramp, D. , Schuppli, C. A. and Fraser, D. (2017), International consensus principles for ethical wildlife control. Conservation Biology, 31: 753-760. doi:10.1111/cobi.12896

[registration_form]

So what’s the justification for people that disturb wild deer with their dogs having to shoot them? If such an action might cause severe suffering and harm why should the law require it?

I often think that the amount of suffering inherent in any community of wild animals is underestimated. Every day vast numbers of animals starve or freeze to death, die from disease or from being chased and then eaten alive by predators. Our population of Sparrowhawks alone inflicts this last form of slow death on perhaps 50,000 small birds every day. A lot of natural deaths are the result of competition between animals of the same species. Every environment has a carrying capacity for the number of animals of each species it can support. For that reason, you have to wonder whether the rehabilitation of common wild animals is ever worthwhile. To be rehabilitated they have to endure the inevitable (and surely hugely underestimated) stress of treatment and a period in captivity. Then are put back out there into the wild. If they make they will only do so at the expense of outcompeting others of their own kind because the carrying capacity of the environment will remain the same. Why bother? Wouldn’t it be kinder to put them out of their misery in the first place?

I used to think that wildlife rehabilitation was largely ineffective. Having been exposed to it a little more over the last few years, I’ve begun to change my mind. It has to be done well, very well and by professionals, however.

Do you have any examples involving common species where this approach has had a measurable benefit to conservation in Britain without increasing overall levels of animal suffering (thorough the rehabilitation process)?

You would think most rehabilitation would be of common species because ‘common things are common’. This looks like a good starting point:

https://veterinaryrecord.bmj.com/content/172/8/211.

I have for some time been involved with the removal of invasive species introduced from abroad. I had expected that the article might challenge somewhat my idea that killing these animals by live trapping and dispatching by shooting is a valid reason for the activity, provided that it results in near extermination of the invasive species at a local level.

As it was not mentioned in the post I’ll continue to hope that it is not relevant in overall animal welfare terms.

I deliberately did not draw a distinction between native and non-native animals. However, if the ethical review is followed then one might expect that the humane killing of non-native animals (eg black rats) to protect hole-nesting seabirds would be considered ethical. One might expect that the killing of buzzards to protect ring-necked pheasants would not.

I think an ethical framework for wildlife and wild space welfare should look at invasive species and in doing so try to look at the best and most humane approach to tackle this…and hopefully in doing so, raise awareness of the problem, engage debate and prevent and reduce further non-native invasive introductions of both flora and fauna.

Wow! Thanks, Mark, for another brilliant blog to start my day – not strident like Derek Gow’s, or lyrical like Kerri ni Dochartaigh’s, but coolly rational and totally persuasive.

Research into animal intelligence and sentience has moved on so far and so fast that ‘traditional’ ways of thinking about wild animals, and dealing with those we find inconvenient or annoying, are simply no longer justifiable. And practices that involve the killing and maiming of wild animals essentially just for the fun of it are no longer acceptable, if ever they were.

What I especially liked was the way Alick did not exempt scientists and conservationists from his analysis – everyone shares responsibility for stamping out all forms of animal abuse.

This blog seems to justify my approach of not killing wildlife where other less harmful and cruel means of managing it are available. The use of under control dogs to replicate the dispersal effects of missing apex predators- namely wolves is one such means.

Well, I am flattered. I am not normally considered rational nor particularly persuasive so that’s nice to read, thank you. I will work on the passion.

You have honed in on one of the most important points: It applies to everyone or it applies to no one. But we need to have high profile early adopters and for that I look to conservation NGOs.

A really interesting post, thanks Alick.

Much thought and action is needed with regards to the anthropogenic effects of human activities on wildlife and wildspace. These considerations need a good framework when applying practically.

As Alick clearly states this isn’t an ethical debate about natural processes…the flight/ fight response has been part of, and engineered evolution. So sparrowhawks eating sparrows and dolphins eating fish is not part of this debate.

For me, a good starting point for ethical debate is considering the five freedoms for animals…and in doing so this also allows protection for wild space, because wild animals need healthy wild space to thrive.

So in brief:

1) Freedom from hunger and thirst;

A natural ecosystem should allow predator/ prey balance and functioning food chain. Water sources should be unpolluted and unadulterated to ensure steady supply of clean water.

2) Freedom from discomfort;

In the ethics of companion animals, this is defined as providing appropriate environment including shelter and resting area. So for wild animals, this would refer to allowing wild space to remain wild and it would give protection to wild space which is essential to the welfare of wild animals. Hence this would give much needed protection to habitats from individual trees to whole ecosystems.

3) Freedom from pain injury and disease

(Note again we are concerned with anthropogenic causes here) Ie; pain and injury inflicted by man…blood sports, setting traps…etc and also looking at disease inflicted upon ecosystems by man, such as high stocking densities of grouse on grouse moors increasing disease risk, pollutants causing infertility in orca, etc etc…too many etcs to mention here.

4) Freedom to express normal behaviour…

This is the fundamental essence of fully functioning ecosystems.

5) Freedom from fear and distress…(note again anthropogenic causes)

Encompasses many issues here…but especially reducing disturbance to wildlife and within this framework need to think about how humans can watch wildlife and enjoy wild space with minimum disturbance of wildlife especially at crucial breeding times.

So thanks Alick once again for this post. I wish I could make the conference but I’ll closely follow the debate.

Thanks for the reply Alick, an to Mark, of course. That coincides quite well with my view.

Warnings abound of pending extinctions, borne out by The State of Nature Report highlighting its decline, yet so called traditional practises continue to take their expansive quota, dismissive of concern. Lost habitat shrinking everything into enclaves, while landscapes are cleansed of the wild intrusion even those species of primary benefit. It is after all a web of life, an interaction, over which we profess an understanding, yet in our arrogance are so dismissive of the consequence of our interface. Yes we urgently need a fresh approach of realism so ably expressed in this blog.

Thank you. It’s the result of a lot of thought over the last 3 years.

I spent a long time involved with the 5 freedoms when I was in MAFF and then Defra. They derive from the 1968 Brambell Report into farm animal welfare and have underpinned a great deal of policy development albeit moderated, sometimes sharply, by politics. They are relevant to wild animals too, of course although applying all of them is difficult since observation is so much more difficult. But combined with an inclusive and transparent ethical approach, there are the makings of significant change.

@gill with regard to anthropogenic causes of disease and suffering would this include removing apex predators such as wolves and then subsequently failing to manage wild deer populations thus allowing them to become overcrowded? It strikes me there is quandary there because both doing nothing and doing something In that situation might cause some degree of suffering. That’s why IMO replicating the dispersal effects of wolves without killing can be justified. Dogs are obviously the nearest available substitute for wolves for many people

Giles – I think we have got your point thanks.

Yes, indeed we have. Thank you, Mark.

The most important part of this proposal is that there are no prescribed or proscribed solutions. If the process is followed through then a proposal to intervene against an individual or a population is presented along with the supporting evidence. If the case is weak or the alternatives have not been considered or implemented then it is unlikely to be considered ethical. Giles’ case has insufficient detail to even consider hypothetically. In any case, there are no free-living wolves in the UK.

Hi Alick

What I’m suggesting is that I be allowed to walk my dog through woods thereby dispersing wild deer hence reducing there numbers in certain areas where they do damage I’m suggesting that this practice might cause a lot less suffering than shooting them.

It’s quite simple really – the deer just run off when they realise the dogs are there

Happy to provide more detail if you could let me know what sort of detail you’d be looking for

I appreciate your enthusiasm, Giles. However, I don’t believe there’s much value in attempting to apply the framework to a hypothetical problem. Having said that, deploying a dog to disperse deer might be good ‘test case’ at some stage in the future since there would widely differing opinions about the efficacy, value and humaneness of such a practice.

Thanks for your interest.

It could be done now for “research and observation” – under the Hunting Act you don’t have to then shoot the deer if it’s a research project. All Giles would have to do is take a notebook and note down all the animals he hasn’t killed.

That would be a good way to get round not killing them.

If the stag hunts get away with using this clause I don’t see why he shouldn’t.

Interesting thread and comments. I’m intellectually and morally sympathetic but can see it being a can of worms in practical terms. Just one example- poisoning rats is clearly a very inhumane way to kill individuals of a social species that’s more intelligent than we’d like to admit (as evidenced by pet rats for instance) . But if I have an infestation of rats in my house…

And while some might be very happy with the ethical distinction between killing mink to save water voles and killing buzzards to “save” pheasants I can think of quite a lot of animal rights enthusiasts I’ve met who would would disagree very strongly. And equally Giles’s hunting parallel with wolves arguably has more substance to it than we might wish to admit – and I for one certainly wouldn’t want to give the hunting lobby any more leverage than they already have.

You could easily end up with a process that has a superficial appearance of objectivity but is in fact both subjective (who’s on the ethics panel and how are they selected?) and unaccountable and just creates a new field for warring ideologies to battle over.

I’m not sure that the ethical clarity we seek can ever be possible – life is messy, ethical priorities often conflict, and other considerations intrude. And that’s just in one person’s life decisions.

I’m also wary of the NE / BAP trap of expending all our energy on process and planning and paperwork and not actually achieving very much. “It would be incumbent on the proponents of intervention to present rigorous cost-benefit analysis of the alternative interventions which take account of the social value of the species in question” sounds like a prohibitively expensive process for anyone without a vested interest – who’s going to pay for this analysis when the objective isn’t profit? And who’s going to have the resources to challenge the analysis of an established mega industry like game shooting? And if the farmers pay for an analysis about how terrible an eagle reintroduction project will be for poor little lambs, who’s to say that the welfare considerations for wild animals will trump those for domestic ones? They can afford better lawyers than us, I’m pretty sure. Be careful what you wish for.

The more I think about how this would pan out in practice, the less I like it. Sorry.

I’m about to get a lot of dislikes, I suspect.

Good points jbc, I too think Giles has a point.

Never fear the dislike button, I think my best score is sixteen.

These are thoughtful and worthwhile comments, Jbc, so thank you. Getting people talking about wildlife ethics is an important first step and we expect bumps in the crowd before the use an ethical framework is routine. I expect there were similar misgivings when the first calls for better welfare of farm and research animals were made.

I’ve struggled with rodents in my house and I don’t pretend that killing can be avoided in all cases. But start with efforts to exclude and deter and, only if that fails, use a humane method to kill. Traps vary in their effectiveness even within one manufacturer so choose carefully (some manufacturers are seeking to collaborate on an approval scheme and not before time). Avoid poisons.

I sit on a research ethics panel. It gives me sleepless nights but it has to be done. Members of ethics panels should be drawn from a wide variety of backgrounds but must include lay members and local residents.

This ought not to be a battle between lawyers. It should be about building consensus. I agree that we must avoid unnecessary bureaucracy.

Money might be a problem but only if we allow us to be lead into the trap that sees all problems as being a matter of profit and loss and ignores the social value of abundant and diverse wildlife.

Have a ‘like’.

Please don’t identify me with the hunting lobby. It’s the hunting act which supports a form of stag hunting- chasing deer out of woodland and then gunning them down. My alternative is the opposite to that. I am simply suggesting that not killing wildlife can be more humane and that it can be justified to not kill even where that means you are breaking the law. There is no necessary correlation between law and ethics – any correlation is incidental.

To be clear, Giles:

1. I have not identified you with any lobby.

2. I have not deemed your proposal unethical.

3. In some circumstances, perhaps in most circumstances, not killing wildlife is more humane than killing them.

I can add no more.

See what I mean about cool and rational? Many people (including me) are reduced to spluttering rage by this kind of twaddle.

Alick, you’re a star!

It took me a little while to realise exactly what it was Giles is saying – as he does express himself in a somewhat provocative fashion – I was especially outraged when I first saw a blog post of his entitled “hunting badgers with dogs”.

From what I understand he uses his dogs to disperse deer by walking them through woods – this clearly constitutes ‘flushing out of cover’ as, like any dog walker he sometimes causes the deer to be driven out of cover. He then fails to shoot the deer – which is illegal under the Hunting Act – the flushed deer must be shot ASAP in order to exempt ‘flushing’.

He’s arguing that it’s less cruel NOT to shoot the deer in such circumstances. Surely he’s right? It seems to me that Alick might think so as he accepts that generally not killing wildlife is less cruel than killing it.

Moreover if this were not the case would we not have to conclude that dog walking in woodland is more cruel than dog walking in woodland and killing all the wildlife one encounters?

Alick points out that the ‘why’ is important as well as the ‘how’ – however if one just walks a dog through woods to exercise it then the EFFECT is going to be identical to walking a dog through woods to disperse deer so can we honestly say it is less cruel?

In actual fact if one is walking a dog to deliberately disperse deer it arguably might be less cruel as one is going to be more conscious of the possibility of an extended chase and therefore may be more likely to take prompt steps to prevent one.

I’ve never witnessed anyone make a rational case against what Giles is saying – generally people either throw insults or dismiss it as ‘twaddle’ which I have to say is more than a little juvenile.

I fear this might be getting away from the overall thrust of the article which is advocating an ethical approach to anthropogenic activities that harm or have the potential to harm wildlife. However, I’ll have one more go. I accept that dogs chasing a deer for a short period may not be particularly detrimental to the deer involved. But that is not the whole story. Presumably they are being chased for a reason, say, because the deer are damaging crops. That might suit the affected landowner but where do the deer go? Someone else’s crops? Further, how does one define a short period. I know from experience that terms like that are difficult to define (‘dogs must be under close control’). Add to that the risk of capture myopathy (https://wildinstincts.wordpress.com/2012/09/09/capture-myopathy/) and what we know about the effect on deer behaviour and the numbers of other species following the introduction of predators (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_wolves_in_Yellowstone), I would want this to be considered in the local circumstances and a comprehensive evidence base.

For what it’s worth, I would have done with it and re-introduce the wolf and lynx.

What is it you take issue with? It makes perfect sense to me..

While I try to avoid sporting metaphors, my advice is always play the ball, not the man. Thank you. You can come again.

Thanks for your replies Alick – you probably don’t remember me but we met at the WAWC conference in Edinburgh a couple of years ago – I came to the delicious meal afterwards but had to dash for the train.

I’m not sure that ‘chasing’ is essential to what I am talking about but it probably helps – I have found a small amount of scientific literature – that might be relevant to what I am talking about – the contexts are slightly different but similar.

The book “Free-Ranging Dogs and Wildlife Conservation” looks especially interesting

https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1456&context=gpwdcwp

https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1977&context=icwdm_usdanwrc

http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1103&context=icwdm_wdmconfproc

https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/icwdm_wdmconfproc/130/

https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/ewdcc3/12/

https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2243&context=icwdm_usdanwrc

https://www.amazon.co.uk/Free-Ranging-Wildlife-Conservation-Matthew-Gompper/dp/0199663211

https://www.aphis.usda.gov/wildlife_damage/nwrc/publications/14pubs/14-152%20vercauteren.pdf

You are an animal abuser who enjoys torturing foxes

Merry – errrr, is that comment really directed at Alick? I don’t think so…

Not sure who that is a response to TBH – personally i think what Alick is saying makes a lot of sense – we should seek out non lethal means of managing wildlife – that’s certainly what I do and promote – nothing to do with torturing anything.

Also as far as alicks comment about a lack of detail meaning my actions are unethical that constitutes a basic misunderstanding about ethics. Ethical decisions are by there very nature made with a lack of sufficient detail. That is a key aspect of the human condition unless one involves an omniscient deity plus access to him/her

Following on from Alick’s comment about controlling rodents in his house – one method is using a cat. The effect of the cat is not only to kill rodents but also to deter them – while. This has to be balanced against the rather cruel fate received by the rodents when actually caught.

Moreover a use of dogs to deter wildlife is using free ranging dogs around farm buildings to control badgers. Badgers can do considerable damage by undermining farm buildings. The presence of a dog or dogs deters them.

I hate to disappoint you, Giles, but I wasn’t at the last WAWC conference.

Ah sorry – was sure it was you

Some very interesting, excellent and informed, comments and replies on this blog. I’ve read every single one.

My opinion is that humans are the most invasive species.

In spite of their being many derelict brown sites in all the towns near to me, the choice is always for more ubiquitous housing on green field sites. None of these sites were empty; they were populated by badgers, foxes, hedgehogs, harvest mice, voles, brown rats, and native birds that nested in the mature trees and hedgerows, including the insects and invertebrates. All of these were displaced. Where are they supposed to find a new home?