Claire Wordley works on the Conservation Evidence project, with an emphasis on getting people to use the available science in conservation – and to test their own conservation interventions. Claire wrote a guest blog, Evidence, Experts and Effectiveness in Conservation, in May 2018. Say hi at @ConservEvidence

Claire Wordley works on the Conservation Evidence project, with an emphasis on getting people to use the available science in conservation – and to test their own conservation interventions. Claire wrote a guest blog, Evidence, Experts and Effectiveness in Conservation, in May 2018. Say hi at @ConservEvidence

Swifter nest building with starter kits.

Adding ‘nest forms’ to swift boxes makes common swifts more than four times more likely to use the boxes, according to a paper published in the journal Conservation Evidence. A simple yet elegant experiment placed nest forms – carved shapes that provide a basis to start building a nest – into every other swift box in four sites, and waited to see where the birds chose to nest. At every site they preferred the boxes with a nest form, using it as a basis to build their nest. Webcam footage also showed that they used nesting material such as small feathers or straw if left in the box. These simple measures could be used to give these declining birds a boost.

Swifts are incredible creatures; they look superficially similar to swallows, but are actually most closely related to hummingbirds. They live on the wing, flying at up to 70 miles an hour, and crossing the Himalayas at a height of nearly 6,000 m. Despite ranging from Africa to Asia, common swifts have declined by over half in the last twenty years and are considered to be endangered in the UK. This may be due to a constellation of factors including agricultural intensification, people hunting them during migration, and loss of habitat; but the loss of suitable nest sites in the UK is thought by many to be playing an important role. Swifts build their nests on vertical surfaces, using material that they catch floating through the air. While they used to build their nests on cliffs or in tree holes, since Roman times they have switched to nesting under the eaves of houses or in the gaps under windowsills. In the UK, they nest almost exclusively in pre-1944 buildings; newer or renovated buildings use techniques and materials that prevent the access of swifts.

To mitigate against this loss swift boxes are added to many buildings, with mixed success. Occupancy rates have been reported to be only around 25%, so any way to make these boxes more attractive to swifts is valuable. The idea of adding a nest form was first written about in 1956 by David Lack, who in his book Swifts in a Tower described adding small rings of straw to swift nest boxes. More solid nest forms, looking a bit like a thick coaster with a concave depression, are sold for the commercial breeding of budgerigars – but how effective they are for getting wild swifts to nest was not tested until 2019. 63 years after Lack suggested the use of nest forms for swifts, ‘Action for Swifts’ tested their use and found that swifts used 48% of boxes with a nest form, compared to 15% without. One of the sites tested was in Lack’s own tower in Oxford. These nest forms cost under £2 each when sold commercially and can easily be made at home from MDF, fibreboard or plywood, making them a practical and cheap conservation solution.

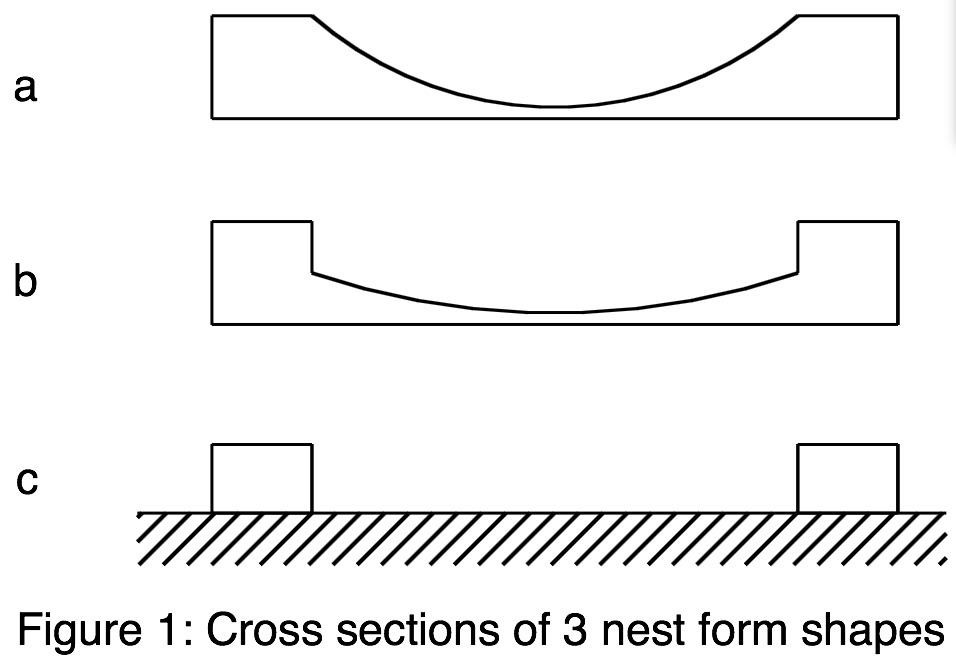

Three types of nest form were used in the study, with different depths and steepness of the concave ‘dip’. Preliminary results suggest that they all worked equally well, meaning that even the easiest to make nest form – with a vertical side rather than a slope – is useful to the swifts. Furthermore, the preference of the swifts for the boxes with the nest forms did not decline over time as the boxes increased in occupancy; even where the swift boxes had been in place for seven years, the boxes with nest forms were still preferred. The next steps are to see whether nest forms increase overall occupancy (i.e. if you have all the boxes in a project with nest forms, what is the occupancy compared to a project with no nest forms).

This simple, cheap measure could be used in every swift box project, and may help to boost the numbers of this incredible but declining bird. This project is also an excellent example of how to undertake a simple but powerful experiment – by placing nest forms in every other box the researcher made the design a powerful replicated, paired, controlled study. We hope to see many more swift-box projects in the UK using these nest forms – and many more swifts in our skies.

[registration_form]

What a brilliant simple idea!

On the subject of what we can do to help: Bto just sent a circular round asking for volunteers to survey birds in woodlands planted 30 years ago under Grant schemes. I wonder how many of those have bird/bat nest boxes in them. new trees are ok but they have no holes in them.

We have Swift boxes under wide overhanging eaves, no swifts yet, but their sheltered roofs are a popular winter roost for a kestrel most years. I cannot bleleive it is the same bird as it has been visiting there for many years now.

Andrew, Swift boxes under wide overhanging eaves should be flush under those eaves, otherwise, as you have found out, you will get predators perching and pigeons breeding on top.

Aah Dick thanks

That could be the problem. there is no soffit board, it is an old barn with assorted timbers for rafters with slates on top and plenty of gaps over the wall plate.. Over the years trees and shrubs have grown up in the garden and it is not such an open aspect is it used to be when we arrived, I thought this was the problem.

The boxes are an old design with a sloping roof, indeed so old that one was recommended to put sloping covers over the holes to stop the sparrows going in, which they still did. (We removed this protection when the sparrows disappeared)

Wood pigeons much prefer the shrubs even by the front and back door I think in some years there are four nests in shrubs against the wall of the house. How things have changed to a new normal. When I was young, pigeons would not stay in the same field as you and we used to marvel at them strutting around the parks in London

If your barn has open eaves, send a photo to actionforswifts@gmail.com and I might be able to suggest something.