Jane is a naturalist, photographer and nature writer living in Dorset. Her work has appeared in books, anthologies and blogs for charities such as The Wildlife Trusts and the International Bee Research Association. When she’s not exploring Dorset’s lanes and countryside she can be found lying on her stomach watching insects in her garden. Jane’s entry for this blog’s Lockdown Nature-writing challenge was shortlisted and can be found by clicking here. Jane is currently studying for an MA in Travel and Nature Writing at Bath Spa University and can be found: www.janevadams.com and on Twitter @WildlifeStuff

On the basis of Jane’s entry in the Lockdown Nature-writing Challenge, and a couple of guest blogs she has written for this site since (Weevils and Wool-carder Bee) I have persuaded Jane to write a monthly article to appear on the last Saturday of the month. June’s article was on Stag Beetles, July’s was about her unmown lawn and lockdown, August’s was about Devil’s–bit scabious and here is September’s…

It’s strange when a smell reminds you of a bee. But that’s exactly what happens each September when I walk past a stand of flowering ivy and get drawn in by its cloying honeyed scent and start my search for ivy bees.

Also unusual, but somewhat uplifting, is to be writing about a relatively new-bee. Colletes hederae, commonly known as the ivy bee, due to its strong preference for foraging from Hedera helix, the common ivy, is a mining bee that was first found and recorded in Britain in Worth Matravers, Dorset in 2001.

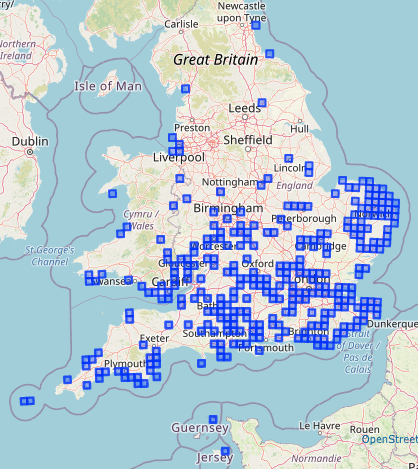

Since then it has spread north at what feels like a staggering rate for such a small insect, with a female bee recorded roughly five hundred miles north, near Sunderland, this time last year.

The ivy bee is also rather beautiful. I may be biased, as I do tend to think all bees are beautiful, but when it first emerges from its nest in late August early September its abdomen is a vibrant mix of orange and black stripes set off against a hairy ginger thorax. These colours do fade during its short life, which only amounts to a handful of weeks, but freshly hatched bees seem to sparkle as they fly from flower to flower in the early autumn sun.

At this time of year there’s still a few solitary bee species on the wing, but the ivy bee is the last one to hatch, a fact that fills me with mixed emotions. On the one hand I love the anticipation of spotting them, but it’s also – other than the odd hardy winter bumblebee feeding on mahonia outside my local Co-op – likely to be the last bee I see until spring, and that feels quite sad.

Which is, I think, even more of a reason to try and spot one, and they are surprisingly easy to find if you have them nesting nearby. You can obviously look for them on flowering ivy, (in my garden they visit ivy that has crawled up an old apple tree), but when they find a place that’s suitable for nesting (usually a south facing sandy bank or cliff, but can also be a closely mown lawn or road verge) they can be found in their hundreds, even thousands. Coming across one of these large aggregations is a wildlife spectacle to be treasured.

A few years ago I heard about an active nest site only a few miles from where I live, and went to investigate. It was on a local golf course, which at the time felt like a strange place to be looking for bees. Having never seen ivy bees nesting before I was thrilled to discover thousands digging nests and hatching from the slope and overhang of one of the bunkers. Amusingly the golf club had erected signs permitting a ‘free ball drop’ nearby if your shot inadvertently came to rest next to the bees. Although this would have been a neat way of extricating yourself from the bunker the golfers didn’t need to fear these bees. The honey-bee sized females can sting (males don’t have a sting), but you’d probably need to pick one up and squeeze it hard to get that reaction. That day I sat within clouds of bees as they nested, mated and hatched. I wasn’t touched by a single bee, let alone stung.

Hatching takes twelve months after the eggs are laid in their subterranean self-dug nests, with males hatching a couple of weeks before females. It’s worth looking out for writhing balls of amorous males all keen to mate with a newly hatched female. In some places I’ve even seen these mating balls bouncing away down nearby slopes like living ginger and black tennis balls.

Try to see one. If you think ivy bees have reached your neck of the woods they really are worth looking out for. They’ll be flying until the ivy stops flowering, but remember, they’ll probably be the last solitary bee species you see until 2021.

Extra information:

Bees, Wasps and Ants Recording Society Ivy bee information sheet

Records of any ivy bees seen can be submitted at the Bees, Wasps and Ants Recording Society at www.bwars.com/content/submit-sighting-colletes-hederae-ivy-bee

They sound fascinating insects, I must look out for them. Has anyone studied their DNA to see if they have low variability due to their recent arrival? And even to see how many initial invasion events there were? Presumably it wasn’t just one original bee, but be interesting to see if it was.

I’m not sure if anyone has studied their DNA for low variability – I’ll try to find out from the experts/scientists on the BWARS FB group. I know they’ve studied there pollen preference in the UK and Europe.

From what I’ve read it sounds as if they had probably been here for a while. Once recorders started looking (after the initial discovery in 2001) they realised they were already pretty widespread in the Purbeck area – there was also a small site in Devon. Last year’s map shows records right the way along the south coast, Guernsey and Jersey. The species is widespread in Europe – although only “described as new to science in 1993 from specimens found in southern Europe” (BWARS info sheet).

thank you for the information

Success. Many thanks to Jeremy Bartlett and David Harper on the BWARS “UK Bees, Wasps and Ants” FB Group (I highly recommend this group if you’re interested in any of these insects) who tracked down a paper on the ivy bee, called “Inferring the mode of colonization of the rapid range expansion of

a solitary bee from multilocus DNA sequence variation”.

Ironically I accompanied two of the authors, Stuart Roberts and Nico Vereecken, on a trip to the Purbeck area many years ago collecting samples of male Colletes hederae – specimens that may have been used during this research. http://homepages.ulb.ac.be/~pmarduly/Publications_files/Dellicour&al2014a.pdf?fbclid=IwAR1McDAxtjFzRt8rIDsRdx1Wf4ol8AD0k7rV2bWsi0Wm5p_Aut4SI3-KIyI

Thanks Jane, well done. I’ll have a read of that. I hope you got your name on the paper if you supplied some of the specimens!

This is brilliant.

All of Jane’s articles are so interesting.

Lots more please on insects and their relationship with arable plants, and if we loose these plants then the whole connected eco system collapses.

Many thanks Thomas. I really appreciate your comment.

A lovely article on an interesting insect I knew absolutely nothing about. What makes it even better is that it sounds as though I might have a reasonable chance of seeing one in the flesh in the near future. I look forward to your next blog!

Thank you Alan. Good luck in your search for ivy bees. It’s always nice when you stand a good chance of seeing some wildlife. They are a fascinating bee so I’m sure you won’t be disappointed.

So essentially a large founder population. Interesting! And you did get an acknowledgement I’m glad to see.

Yes, how embarrassing that I’d completely forgotten about that paper. I spent an amazing day on Purbeck with Stuart Roberts and Nico Vereecken – two very inspiring gentlemen.

Flowers on a large clump of ivy growing over an old tree stump have just opened up in today’s sunshine and it is “alive” with Ivy bees. Aren’t they gorgeous! I had not appreciated how small they are. It’s a bit high up for me to get a decent photo though there’s another mass of ivy nearby that will be in full flower in a few days so I’ll try to remember to check. I have submitted the sighting to BWARS – hope they accept it without any photos. Loved the blog again Jane – keep going. I so look forward to them each month.

We have about 10 now on our flowering ivy – plus some glossy bright bronze and green flies (?) and several red admirals and commas .

The ivy really does pull in the last of the insects at this time of year. I often see hornets and other wasps on it as well. I’m not sure about your fly (not really my area, but hopefully someone else will be able to make a suggestion) but it sounds gorgeous.

Thank you for your kind words, Hilly. I’m sure they will accept your record without a photo, but if you do manage to photograph them it’s always worth sending in another record.