Soaring invertebrate life at Yorkshire biodiversity hotspot bucks global trends

Woodmeadows could help reverse UK’s decline in wildlife

More than 1,000 invertebrate species – including over 30 with a high nature conservation status – have been identified at a pioneering 25-acre nature recovery project created by the Woodmeadow Trust near York, on a site which was effectively biodiversity-free only a few years ago.

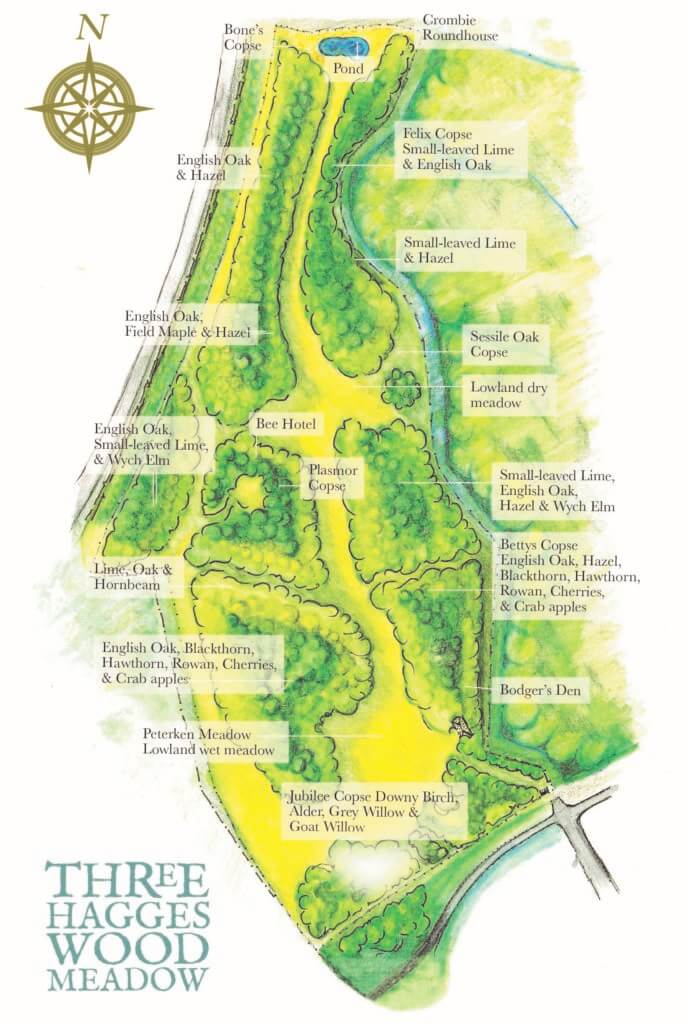

The findings at the charity’s Three Hagges Woodmeadow – created in 2012 on a former barley field – offer hope of rapidly tackling declines in nature by establishing similar biodiversity hotspots UK-wide.

Little known in the UK, woodmeadows are mixtures of woodland and meadow that combine the biodiversity of both habitats, and are exceptionally rich in life. Over 60 flora species per square metre have been recorded in woodmeadows in Scandinavian and Baltic countries, where they were common until the last century.

“Wildlife has moved into our woodmeadow at a speed that’s taken experts by surprise, even though the site is in its infancy and won’t mature for many years,” said Ros Forbes Adam, Project Leader at the Woodmeadow Trust.

“This is a real cause for optimism. It shows that woodmeadows could help reverse the UK’s catastrophic decline in biodiversity, if created on a large scale and connected to other habitats to form wildlife corridors. Our aim is to see a woodmeadow established in every parish in the country.”

Painstaking annual surveys since 2015, mostly carried out by expert Andrew Grayson, have so far formally recorded the presence of 1,113 invertebrate species – including a wide variety of ladybirds, moths, beetles, grasshoppers and spiders – with more being discovered all the time.

A wealth of insect pollinators, attracted by a huge diversity of wildflowers that form a blaze of beautiful colour in the spring and summer, includes 34 bee species, 26 butterfly species, and 43 hoverfly species – none of which would have been found on the site when it was a barley field.

Butterflies include the dingy skipper – a species usually found on chalky soil, and unexpected in Escrick – marbled white, and purple hairstreak. Bees include the red mason bee and wool carder bee, and bumblebees such as the tree bumblebee and red-tailed bumblebee.

Three Hagges Woodmeadow, on the Escrick Estate between Selby and York, is a centre of scientific research, with national experts monitoring mammals, birds, insects, spiders, reptiles, amphibians, wildflowers, trees and soil.

The aim has been to attract and boost species that should be widespread in the UK, although unusual sightings include the yellow-legged clearwing – an insect rarely documented since records began in 1883 – and the third-ever recent British record of the ruby-tailed wasp Chrysis corusca.

Biological richness is maintained and boosted by agricultural methods, including haymaking and grazing, while the trees will be coppiced for poles and charcoal once they are large enough.

The messy edges between woodland and meadow offer niches for a wealth of species – a system famously described by Charles Darwin at the end of The Origin of Species as a ‘tangled bank’.

Adding a pond to the woodmeadow has attracted further species, including dragonflies, damselflies, water beetles and pond snails, and offers a breeding site for newts and frogs.

The Trust says woodmeadows could help transform the UK’s crippled biodiversity. In living memory, the UK has eradicated 97% of wildflower meadows, two-thirds of its orchards, hundreds of thousands of ponds, hundreds of thousands of kilometres of hedgerow, and has become one of Europe’s least-wooded countries – with 56% of species in decline and 15% threatened with extinction.

Because woodmeadows are superb carbon dioxide sinks, they can help tackle climate breakdown. Woodland can store up to 12 tonnes of carbon, and meadow three tonnes, per hectare a year.

Woodmeadows can be any size, and can be created in gardens, urban areas, parks, farmland, and community woods. Orchards, mini-meadows, hedges and woodland can be turned into types of woodmeadow by planting pollinator-friendly shrubs and wildflowers beneath native trees, and ensuring lots of habitat edges.

The Trust’s new short film Woodmeadow: Nature’s Capital – showcasing the wealth of life that can be supported by these rich pockets of nature;

The Woodmeadow Trust is a charity taking action for nature and people, by creating woodmeadows and inspiring others to plant and protect them. See www.woodmeadowtrust.org.uk.

Ends

[registration_form]

This is brilliant – those images of extensive hay/wildflower meadows or chalk grasslands where there isn’t a single bush or clump of nettles from one corner to the other were just as bloody depressing and unimaginative as the standard tree planting exercise with as many plastic tubed whips stuck in the ground as was physically possible. This is hardly creating an all important habitat mosaic – which is almost certainly what our wildlife evolved with not this grotesque compartmentalisation. The RSPB adopted a policy of having 5% of their chalk grassland under scrub a while ago and I’ve always felt any meadow over a certain size should contain at least one pond. I hope though that they do their best to create and maintain deadwood on the site, I’d rather see the products of coppicing provide habitat piles and logs for rotting down – the income from poles and charcoal won’t be that great and TBH invasive rhoddie would be better for charcoal production, it’s too bulky to just leave to break down without smothering the site. I notice Derek Gow isn’t too keen on what’s actually an agricultural entity – chalk grassland and water meadows – being passed off as a natural habitat.

It would be good to see it pointed out that ‘scrub’ isn’t a dirty word in fact the much lauded hedgerow is just it in a continuous linear form. I suspect scrubmeadow might be a more exact term for what they’re doing here. I also have a wonderful image of one day a group of volunteers with nursery grown thistles, brambles, docks, plantains, nettles, willowherb and burdock decanting them from flowerpots and putting them in a specially prepared piece of ground, with the same diligence others put begonias into flower beds, to create special ‘weed’ patches. Way back in 1978 I sent a s.a.e (that’s Stamp Addressed Envelope for any young uns) to Wildlife WATCH for set of A4 notes on wildlife gardening. I always remember that at the very beginning they stated a garden could contain more wildlife than a similar area of countryside because it could contain many mini habitats. Hopefully this point is finally spilling over into the conservation world. This is a fantastic piece of news to start the day with – reminiscent of what’s happening at Knepp, perhaps in a more bite sized portion that will help get things going in more places.

Wood meadows and wood pasture are much forgotten and overlooked habitats in this country. I and my partner (she is a botanist) recently had a trip to Estonia where these habitats are very common. Some of these habitats dated back a thousand years, and were amazing for wildlife. They are particularly good because they support such a very wide range of flora and fauna. They don’t just concentrate on one aspect of wildlife.

We. need many more wood meadows and wood pastures in this country.

That’s how you do it.

The Wildlife Trust and RSPB please take note; these people deserve more of the funding that’s dished out they don’t seem to waste it on tarmacking the car parks, plush new offices or building toilet blocks.

Slightly envious about the elm and small-leaved lime, we have a bit of lime, but as yet no elm, but it’s on the list. I’ll take the Dingy too.

And the important statement “the inappropriate planting of tree”.

For once it’s nice to hear people talking sense.

Aren’t gardens, if ecologically healthy, woodmeadows? Most of them certainly have herbaceous dominated habitats and trees in or nearby. I not heard though that many gardens had this level of richness, even larger ones. Mine is certainly (intended to be) a mini nature reserve, in which I also grow a few of my preferred plants.

Perhaps few people try to make their gardens ecologically healthy, but I’d had the impression many people were trying to do that.

You might be surprised at the number of invertebrate species that can occur in gardens. Many regularly moth-trapped gardens have recorded well over five hundred species of moths alone (admittedly some of these will be passing through the garden). Jennifer Owens undertook systematic monitoring of species in an ordinary medium sized garden in Leicester through the 1970s and 80s with the assistance of experts in various taxa (she was a university lecturer) and over a fifteen year period recorded a very impressive 1782 animal species and 422 plant species.

I would guess that the total list of invertebrates at Three Hagges will continue to rise well above the number recorded so far.

I’d forgotten about her. I believe there were several species of parasitic wasp new to Britain (to the records anyway) that were found in her garden and a couple that were new to science. Not bad, discovering new species in your garden.

But then why is invertebrate life in such decline? Approx. area of gardens in the UK: 40million hectares; estimate of % of gardens not strimmed, poisoned or decked into sterility: 30%? Can it be less than 10%? doubt it’s more than 50%. So between 4million and 20million hectares of fairly wildlife rich habitat just in gardens(??) widely spread and mostly contributing to metapopulations.

So if it has the richness of biodiversity that Hagges WM has, why is insect diversity and biomass in freefall? Any more knowledgable people out there with suggestions?

We have 8 acres of wet, unimproved meadows, plus an acre of garden, that we have been managing for wildlife for 35 years. when we used to have cattle grazing, 30 years ago, they ate off a lot of the new tree-sucker growth- well in fact all of it; and come to think of it, the rewilding projects I have read about in Europe and at Knepp, depend upon large herbivores and re-introduction of European Bison etc. Horses do not graze enough on small scale meadows, but cattle and sheep graze too much.

I guess it is about stocking densities and fencing. Again, more difficult on our small scale when we are dependent on local farmers for grazing, and they tend to put on too many animals and leave them on longer than I want (in spite of contracts) This happens on our NWWT reserves too. Is hasn’t been economically viable for local farmers to keep cattle for many years here, and after Brexit it won’t be for sheep either. Without bi-annual mechanical intervention our fields would soon become dense woodland.

So not sure woodpasture can exist by itself on small patches. What to do?

All grazing throughout the spring and summer months damages meadows regardless of which animals that are doing the grazing.