I came across this paper partly because it cites a paper I co-authored on Roseate Tern conservation many, many years ago. And the Roseate Tern is a species very close to my heart (see Fighting for Birds Chapter 3, In the pink – roseate terns). It’s a fascinating study which unlocks some of the facts that we pondered over and wondered about back in the late 1980s.

Roseate Terns go to the seas of West Africa in our winter and they, like many other terns, were trapped there by coastal human communities. Although Roseate Terns are rare terns, and therefore make up a small proportion of all the terns along the coast (Sandwich, Common and Black in particular, but other species too) they seemed to be particularly vulnerable to trapping and it probably was the case that this trapping was a factor in the decline of the species on its European breeding grounds.

By the way, the trapping was less subsistence trapping for food and more commonly little boys at a loose end.

But most of the ringing recoveries of Roseate Terns in West Africa, and indeed most of the sightings in Ghana were in the early part of the ‘winter’ – October-December – with a dearth of records after Christmas. This made sense because it coincided with the main season of the coastal fishery which depended on small fish that were just the species that the terns fed upon, and this further made sense because there was an upwelling current at around that time of year which brought nutrients to the upper waters of the sea and caused a bloom of plankton and a rise in fish numbers. But where did the terns go after Christmas?

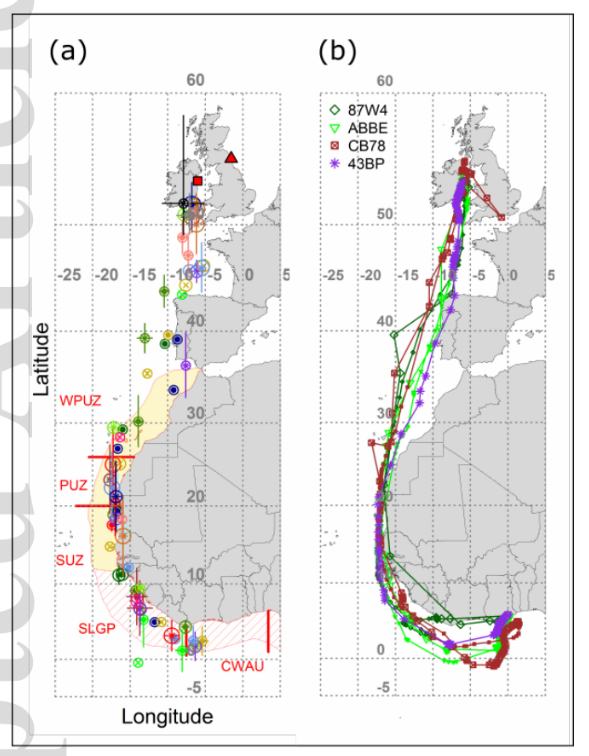

This study used geolocators, put on Roseate Terns at two colonies I know well, Rockabill in Ireland and Coquet Island in Northumberland (I always try to glimpse it if on a London-Edinburgh train). Geolocators record where the bird is (daily at least) but have to be retrieved from the bird for their information to be accessed – they collect loads of data but don’t transmit it (so you need a species that survives and can fairly reliably be recaptured).

This paper confiirms that Roseate Terns go to where we thought they went (unsurprising – I, and others, have seen them there!) but it reveals loads of information. Where do the terns go after Christmas or in late autumn? It seems that some start moving back along the West African coast towards us but many stay in the same places. The results show that a lot of the time is spent far offshore – certainly way out of sight of land, and so the large flocks of terns I’ve seen on salt flats west of Accra, and at places all along the coast of Ghana, are only a small part of a much larger population. It’s facinating and I’ll spend more time looking at the paper.

As with all migratory species, there is a need to ensure the protection of food supplies and habitat throughout the annual range if the species is going to prosper.

But this is yet another in a long line of studies using geolocators which demonstrate how much valuable information can be collected through their use. Is it the end of ringing? Certainly not. Have we passed peak ringing? Quite possibly.

[registration_form]

Certainly peak ringing for migration is currently over and has been for a long time for larger species. However, the use of GPS and geo-locators brings up an interesting question. When this paper is published and we know their migration routes will anybody ever put a geo-locator or a ring on a roseate tern ever again?

Electronic tracking is woefully expensive. As a result it’s only done in funded projects by professionals. However once the data is gathered and the papers published what will happen. Funding science is increasingly driven by novelty and nobody is going to put money into a project when it’s been done already. it might be 20 years before the question becomes worthy of funding again.

If roseate terns, or any species, starts to change it’s distribution it’s probably worthwhile to find out when it’s happening. Systematic ringing can help but the volume of data generated is tiny. So it seems there is a gap between low-tech (ringing) and hi-tech (GPS transmitters) that will need filling. Perhaps when the cost of GPS transmitters falls to zero (don’t laugh) the problem will go away.

There are systems like MOTUS, https://motus.org/ which could be really interesting but it’s still expensive.

What to do in the meantime?

Stuart – thank you. Interesting points.

I remember watching a short film once (RSPB I think) about what happened to roseate terns in West Africa and as you say the big issue was small boys. They ‘entertained’ themselves by breaking the bird’s jaw so the lower beak drooped uselessly reducing the snips delivered while they were played with for a short while. When I was their age my classmates loved to go out in the nesting season and trash every nest they could find complete with nestlings and eggs – I clearly recall a path on the way to school that was liberally decorated with smashed thrush, dunnock, robin eggs in spring. It wasn’t a very happy situation to be a nature lover in. The biggest boost for the local birdlife was the coming of bedroom tellies then Playstation.

Anyway I think the situation with the roseate tern in its winter range isn’t an inevitable consequence of poverty (and thereby us affluent westerners shouldn’t pass judgement) it’s down to basic human failings that keep us all back and need to be countered – it’s not as if we are critical of unnecessary animal suffering in other countries and not in our own. Traditional magic is big in Madagascar and one of the most supposedly potent charms is a talon from the island’s endemic fish eagle. For the ‘magic’ to work and the power to transfer from the bird, the talon is cut off while it’s still alive. The Madagascan fish eagle is one of the rarest birds of prey in the world, in fact it was studied by Ruth Tingay of RPUK fame. Researchers have found dead eagles with a missing talon, once one that was still alive, but couldn’t be saved obviously. I hope this was something Ruth never encountered.

Would the ending of this horrendous practice materially effect the people of Madagascar? No, like ending Driven Grouse Shooting the money would be spent elsewhere probably on something more beneficial which wouldn’t be difficult. It would mean one hell of a step forward for the fish eagles though. However, it means tackling ‘tradition’ which also means this will cause the frantic wringing of hands in some quarters. I only found out about it because this was mentioned in a truly Encyclopedic book on Malagasy wildlife. When I tried googling about it just now all that came up was the very general ‘persecution’.

It should have been enough that wildlife was threatened by totally superfluous stupidities (such as DGS and ‘lucky’ eagle talons) on top of our massive consumption of natural resources to make a serious effort to stop them decades ago, but political cowardice got in the way here and abroad. Will it take a pandemic almost certainly caused by rare animals being turned into a tit bit to finally stamp out the most utterly pointless and therefore worst abuses of the world’s living heritage? I’m still waiting to see significant attention given to this in the media when it’s both an incredibly relevant issue and there’s no better time given a particularly large and captive audience. Maybe the bulk of the conservation community is still lacking the backbone to say what needs to be said not just for the survival of actual species, but for actual human lives too.

With the advent of geolocators and sat-tagging, ringing now appears to be a very resource intensive operation (dare I say hobby) with outputs which in terms of the effort involved are very expensive?

There are hundreds or thousands even, of volunteers needing to be licenced etc., spending thousands of hours a year ringing when it sometimes seems as if a well placed geolocator can illuminate bird habits better than decades of ringing. I’m sure the BTO could find valuable work for displaced staff whose ringer’s licensing role has become redundant. I can appreciate that ringing might provide a person a grounding in safe handling of birds in preparation for future sat-tag or geolocator work, and that occasional ‘interesting’ rarities might turn up but I have come to the view that ringing has passed its sell-by.

There is a mountain of information to be discovered to assist in species and habitat conservation from the study and monitoring of other biological Orders and the disproportionate amount of person hours going into bird ringing in modern times seems to be a mis-allocation of a valuable resource. How many ringers could be persuaded to change to butterfly/dragonfly/hoverfly monitoring instead?

Please be gentle in response…

Geolocators do of course require recapture of the bird. There are plenty of species and scenarios where the chances of achieving this are rather slender so I think it is a little early to say that ringing no longer has much purpose. Satellite tracking and geolocators clearly offer fabulous new insights into bird behaviour and ecology but I feel ringing, especially combined with colour-rings or telescope readable engraved rings can still yield valuable information.