New maps reveal how the UK could deliver the 2 billion trees recommended by government advisors

- New research analysing soil types in the UK can be used to determine where woodland expansion could be focused in the future as the UK plans for 2bn new trees

- The analysis warns that planting the wrong type of tree in the wrong place could hinder the UK’s efforts to tackle carbon emissions

- Native broadleaf trees offer the best return in locking up carbon and supporting the UK’s struggling woodland wildlife

New analysis from the RSPB reveals where new woodlands could be created to have the biggest impact on climate change and reducing carbon, whilst also being in harmony with nature. It warns that planting trees in the wrong areas could hinder the UK’s efforts to tackle the climate crisis and harm some wildlife.

In 2019, the UK Committee on Climate Change, advisors to governments across the UK, recommended that 2bn new trees and a 40 per cent increase in woodland would be needed to help the UK reach net zero by 2050. Combined with decarbonising the energy sector and changes in transport and other industries, more trees and woods will play a crucial role in how the UK reduces carbon emissions.

This scale of land use change presents both opportunities as well as real risks for nature. Today, the RSPB is releasing new research which maps where tree planting in the UK could make the biggest difference for nature and climate change.

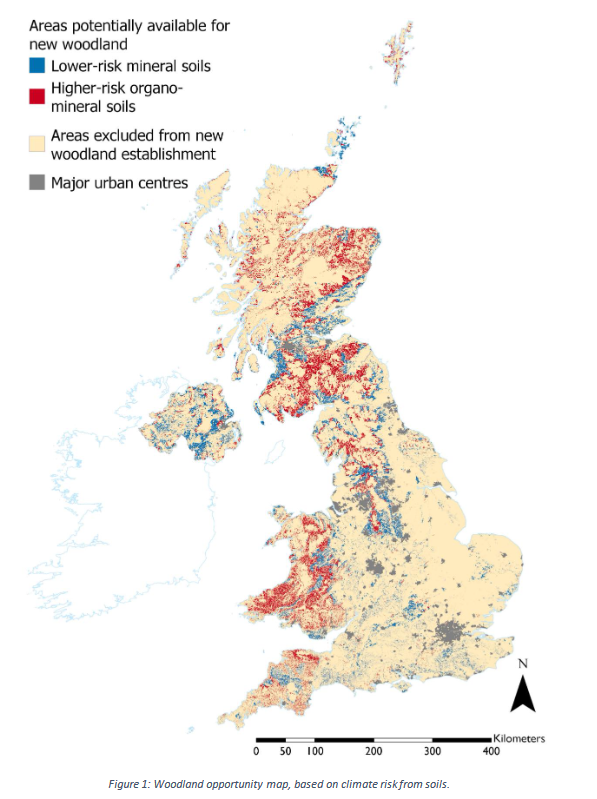

Scientists at the RSPB compared soil types to assess the climate risks of woodland creation. Some soils are rich in carbon, and although new woodlands could be created on these, there is a danger that we could lose more carbon from the soil than new trees would absorb, at least over the first few decades. Woodland creation on mineral soils, with lower levels of carbon, pose a lower risk for the climate.

The new maps reveal that the UK holds enough lower-risk soil to meet the Climate Change Committee’s most ambitious woodland expansion targets. However, the study warns that if the woodland expansion extends into the higher-risk soils area then the governments of the UK must adopt a strategic approach if they are to avoid increasing carbon emissions.

More work is needed as even in lower risk areas any woodland expansion should consider the impact on existing species and habitats that may be harmed by certain types of woodland creation.

The study also looked at the differences in carbon sequestration made by different types of woodland. Finding that, over the long-term, native broadleaf trees absorb and continue to hold more carbon and benefit wildlife than some fast-growing conifer species such as Sitka Spruce.

Tom Lancaster, the RSPB’s head of land policy said: “Today just 13 per cent of the UK is covered by woodland, and new woodlands could play a key role in tackling the climate and nature crises. For this to happen we need to ensure that we plant the right trees in the right places. This means looking at our native trees and woods so that we are expanding our broadleaf woodlands into areas of land that are not currently locking up carbon so that we can use our trees to absorb and store carbon long-term.

However, the UK produces so much carbon that any expansion of our woodland can only play a small part in helping us to get to net zero. At a time when our woodland wildlife is in decline we should be looking at tree planting as a way of restoring vital habitat and tackling the nature crisis as much as the climate crisis. Just as native broadleaf trees are better for long-term carbon storage it is also essential for helping halt the decline of our woodland species. Through strategic planning and looking at how we protect nature we can revive our world.”

To find out more about the UK carbon maps visit this link .

ENDS

[registration_form]

As usual the RSPB is “on the ball” and “ahead of the game”. Well done RSPB. All this preliminary assessment work that they have done is vital for achieving successful tree cover and avoiding destruction of our wildlife plants and insects.

Whether the U.K. Governments will see it that way I am not sure. I think there is a good chance, for example, that the Scottish Government will, but I doubt that the rather stupid and wildlife unfriendly Government in Westminster will.

Our moorlands-with their wide vistas are often regarded by the general public as having “beautiful views” but actually they are devastated landscapes. In bygone times much of these vistas would have Ben covered in trees and inhabited by lynx and wolves. They remain devastated landscapes because of burning and over grazing by especially sheep such that natural regeneration of trees cannot happen. Allowing natural regeneration of trees is much more preferable to planting (which may be necessary in some places). The Cairngorms Connect Project is a great example.

So one of the best ways of gaining more trees and restoring devastated landscapes is to drastically reduce the level of grazing in our uplands AND of course halting all burning.

It can therefore be seen that most of these environmental issues especially in the uplands are linked. Stop the burning and the excessive grazing and trees in most places will return. No one is suggesting that all upland moorland should be tree covered especially not the peat bogs, but there are just miles and miles of devastated landscape in Scotland and Northern England that could sustain trees with sympathetic management.

Banning Driven Grouse Shooting with it’s associated very bad management of our moorlands as well as drastically reducing sheep grazing is very much the best way of achieving a lot more trees and therefore not needing much planting.

And to make the case for at least some tree cover on grouse moors even stronger there’s slowing run off and reducing flood peaks downstream too. If you think that keeping homes dry shouldn’t be compromised by killing birds for fun then please sign this petition just remember to click on the small black ‘Sign This’ box after ticking ‘I’m not a robot’ http://www.parliament.scot/gettinginvolved/petitions/PE01850

Interesting and as ever RSPB does the research and offers a proper sensible way forward, whether it is adopted is entirely another matter and one for politicians so what happens is anyone’s guess.

Alan is not entirely correct Blanket bog and other wet areas of peat were at best sparsely wooded or indeed unwooded, probably forming a mosaic of woodland scrub and open areas of bog much as parts of Scandinavia and indeed Russia or Canada are now. In the medieval period much of the Central Pennine uplands at least were grassland grazed by hordes of sheep owned by Cistercian abbeys, hence names like fountains Fell or fountains Earth. Other than that I agree entirely Alan.

In the medieval period it was much warmer than today. I look forward to the restoration of the monasteries and reintroduction of monks to their former sunlit uplands

“Forestry is another vital part of the puzzle when it comes to trees.”

Deeply insightful

There is a huge and fundamental truth in RSPB’s map: the highest, wettest ground is actually not a very good place for trees. The lower, mineral soils identified by RSPB – you need to look at the map in detail to pick out what becomes almost invisible on the ‘big’ map above – really are the right place for trees. Trees were forced up the hill by agricultural policy, but in fact, today, many of the lower sites identified by RSPB would make sense, creating rather better wooded mixed landscapes. Better soil mean more scope for different species – I’d advocate at one end much more native broadleaf, at the other some of the huge range of species that might have been here before the ice ages. However, I do feel that woodland biodiversity will be overwhelmingly about that huge elephant in the corner – the 500,000 hectares of neglected woodland in England. Whilst this report sets out to make a particular point, optimising the benefits – and avoiding the pitfalls – of new woodland planting must take into account the full range of benefits which may produce rather different outcomes – for example, and most relevant during Covid – the social & health benefits of more woodland and other more natural habitats close to where people live. The risks are on the whole easier: it is what is there before that is the key. If it is biodiversity, carbon or landscape valuable planting trees is likely to be a negative. If it is improved agriculture (and remember that many ancient woodlands were lost to post-war agriculture !) there’s a good chance it’ll be a plus.

I realise this map is in relation to soils, and that natural regen ( or planting seed) is preferable from the Carbon perspective,but i dont get the very large areas excluded from new woodland developement, it does not match what is happening on the ground, indeed Cairngorms Connect should not exist by this criteria.

Talk about locking the stable door, once the horse has bolted? Two words come to mind with this statement – bleeding and obvious. It’s taken the RSPB hierarchy over 100 years to come to this conclusion after years of mass violation of conifer plantations.

The cynic in me couldn’t possibly comment on the thumping big grant, which will be available, so is the charity joining the list of the merry throng that see ‘that there’s gold in cupressaceae?’ If the RSPB is so clever why hasn’t it planted trees to create woodland on its reserves before? No money in it, couldn’t be arsed? – Probably!

The interesting feature on this graph is the year 43, that’s when you can maximize your profit from conifer planting, that time-period is within a normal lifetime of an individual. There’s no money in planting broad-leaved forestry – to create a fully diverse forest will take hundreds of years. If the Government statement had said we are creating new broad-leaved woodland for future generations to appreciate – then great– bring it on. But it hasn’t like everything else this lot does it’s short-termism.

We also believe too much in what these conservationist write, natural forests and woodland are not created by planting masses of trees in plastic tubes in the ground, woodland starts off as growing shrubs and plants some of which we would rather do without, but they’re important and the whole ecosystem starts from scratch there. How do I know? Well I can across the cattle grid and walk into any of the fields and see it happening before my eyes – you called it rewilding, I call it nature’s landscaping.

“what these conservationist write”

Part of the problem is that writing nothing is a problem

“to create a fully diverse forest will take hundreds of years”

And HS2 is undoing some of that, isn’t it? And those damn conservationsists are questioning the reasons behind HS2. The woodland may be replanted, but there is no guarantee that what they are planting will last the same period of time.

A proportion on RSPB reserves will be for marshland. And wetland. And peatland (and reclaiming peatland). And shoreland. Not exactly places conducive to a lot of trees.

Remember that the RSPB (and its members) put their own money into reclaiming some of the peatlands of the flowcountry. Drained and planted (with supporting government grants, no less) for coniferous forestry. (I’ll leave a dividing line between “forest” and “forestry”).

Increasing the amount of woodland does not necessarily do that much for reducing the decline in woodland species. Many new woodlands just become the existing habitat + trees. We haven’t actually lost much actual tree cover but we have lost a lot of good habitat. To restore that we need to start managing our existing woodlands better as well as trying to establish new ones.