Nick MacKinnon is a freelance teacher of Maths, English and Medieval History, and lives above Haworth, in the last inhabited house before Top Withens = Wuthering Heights. In 1992 he founded the successful Campaign to Save Radio 4 Long Wave while in plaster following a rock-climbing accident on Skye. His poem ‘The metric system’ won the 2013 Forward Prize. His topical verse and satire appears in the Spectator, and his puzzles and problems in the Sunday Times and American Mathematical Monthly. Email: nipmackinnon@gmail.com

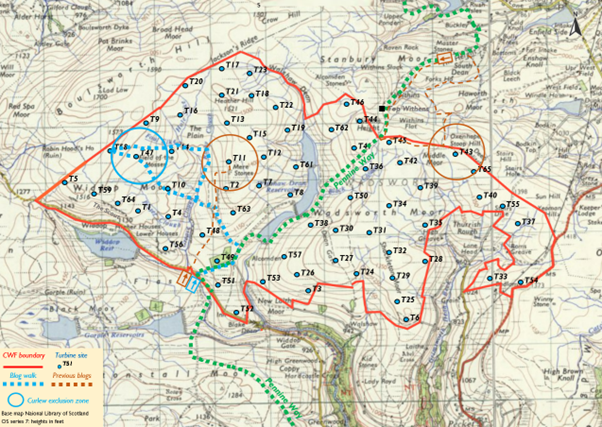

Turbine 47: Field of the Mosses SD 937 345, what3words ///fresh.lifted.grips

30 January 2024 Ali floated the idea of coming on a turbine walk. We are to meet in Hebden Bridge Co-op car park, where two geese are patrolling the bays like traffic wardens on performance-related pay. One should not make assumptions, but I am 97.3% certain Ali will be a vegetarian, so I buy an egg & cress sandwich and a banana for lunch, and a bacon roll for my breakfast before she gets here. We agreed 10 am, and it is an instant measure of her consideration that she arrives exactly five minutes early, twenty seconds after I finish a third bacon roll. We are on a tricky mission: a long walk to somewhere out of this world, with somebody new whose love for the strangeness is uncertain. We are compounding the trickiness by going with Bob Berzins, whom we don’t know either, and who is coming all the way from Sheffield.

Ali is a musician. She has been an acupuncturist and piano tuner. The late Matthew Sweeney said: “In a poem you take two things that won’t stand up on their own and lean them against each other.” You could write a good poem about an acupuncturist, and a better one about a piano tuner. It is when you lean them against each other that you have the chance of something amazing, and when I was a ruthless competitor in the big poetry competitions, this would have been a £5000 forty-liner by nightfall. It is only to stop dozens of poet-vultures from flopping down by this prime case of Sweeney’s Law, that by the time this blog appears I shall have written ‘Her well-tempered needles’ and stuck it in the Bridport Prize, so, as Princess Anne says, they can naff off.

We talk about how music in schools has evaporated. Ali supports a Todmorden charity Music for the Many that pays for instruments and lessons for children whose parents struggle to make ends meet. I was moaning once about the Bannister-level sums I was shelling out on music lessons: electric guitar, two clarinets, two pianos, Yamaha organ, organ-organ, and a bassoon. The mother of my three sons said:

“What is there better to spend our money on than our children’s music lessons?”

This ought to be chiselled into the concrete lintel of the Department for Education. Click here and send Music for the Many the price of a bacon roll. Three bacon rolls.

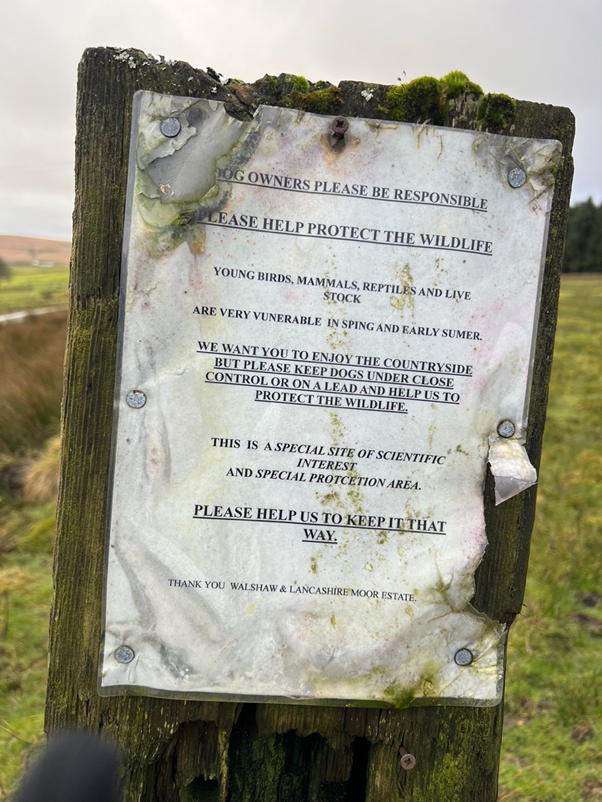

Bob is at Clough Foot and we start up the tarmac, as it was a soaking yesterday. Bob mentions he is a fell runner. Vegetarian Ali is as fit as … umm… a butcher’s dog. I am me, but fresh from Season 2 of The Traitors have learned the survival value of micro-manipulation when among strangers. I let Ali interview Bob, which reduces their air intake while my turbo cranks up to the frightening pace. They are not trying to burn me off: they are simply in cruise control. I also encourage Ali to take lots of photographs, which is why this blog is so well illustrated. Across the rejected shots is cast the shadow of a doubled-over man gasping for oxygen. Her first photograph is so packed with ironies about the management of Walshaw Moor that it can speak for itself. It would never have occurred to me to read this sign, let alone photograph it.

Bob Berzins is, among much else, a retired counsellor, bird maven, thriller writer and peat activist. He denies scientific expertise three times before the first grouse croak but is blessed with a talent for explaining. He was crucial in the Mark Avery campaign against the new shooting track across the moor. As soon as we get to the deep bog, Bob slows from Roger Bannister to Richard Bannister pace, because he is suddenly in his element, like a salamander at a barbecue. Ali’s photographs will have to convey what words can never say about Bob on the peat.

Look at the depth! Two thousand millimetres at one millimetre per year takes us beyond the Crucifixion, which Isaac Newton reckoned was on Friday 3 April 33. Bob doesn’t believe the developer can use miraculous ‘floating roads’ to deliver the 70,000 cubic metres of concrete for the foundations, 195 blades each 50m long, and 65 steel towers 100m high. One hundred metres! It took Usain Bolt 9.58 seconds, and even Ali and Bob have only recently gone sub-eight. Instead of walking on water, normal roads will be chopped down to the bedrock, leaving the remaining peat cut into sections like an industrial tray bake of brownies, with the cookie cutters left in. The moist portions of chocolate yumminess will then dry out, and the vast sequestered carbon of the whole moor will be at stake, not just the huge quantity directly excavated for roads and foundations. This is the carbon calculation, and I will put my head under that bonnet during a moody wet walk by myself, but in the meantime Jenny Shepherd’s group have a grip on it like a Perdix stoat trap.

Bob lives in Sheffield. This moor isn’t in his back yard. He says, “You might build a wind farm on that hill over there or that one. It’s just as visually intrusive over there. There are curlews and lapwings over there. But what you can’t do is build it here, because this is blanket bog, it’s protected up to your eyeballs by law, and is in carbon terms the British equivalent of the Amazon rainforest.” This is the Bog Argument against the Calderdale Wind Farm, and we shall come back to it again and again because if you get too far from the bog then you are too far from the national and global good. Bob suggests we start here, a story in itself.

Opposing the bog argument is £500,000,000 of Saudi money, which is longing for a home in temperate Britain, where we dutifully pay our electricity bills in advance, and haven’t had a glorious revolution since 1689. After all, there are only so many Premier League clubs a Crown Prince can buy before the fans notice that the teams might as well be rodded together like table football for all the spontaneity they are showing.

Bob stands astride a man-made drain, called a grip. “The moor is managed for grouse, and they need young heather. The heather prefers dry ground, so for many years the owners wanted the water off the moor asap. As you see there are a lot of grips, but some of them have got a series of turf dams in them now. Public money pays for that: £200,000 here. That’s all on top of the annual subsidy the owner collects. The hope is that by slowing the flow you re-wet the peat so it continues to act as an enormous carbon sink, won’t catch fire so easily, and the flood risk in the Calder is reduced.”

Some of the dams are working. Others have found it a bit wet lately, and water pours through one of them into a foaming brown plunge pool like the jacuzzi at a Yorkshire Water office-awayday. Bob came up here at the height of Storm Dennis in 2022 to film the “completely ineffective damming of the grips”, and that is OBE-level devotion to hydrology.

Ali has walked on grouse moors for 40 years. I have climbed over 200 Munros. Neither of us has ever seen a stoat trap, but they just come to Bob, who shows us two: he is the snare whisperer. One is in a wooden tunnel under some turfs. The other is a Perdix body-grip kill trap mounted on a pole. When set, they are baited with an egg. YOUNG MAMMALS ARE VERY VUNERABLE IN SPING AND EARLY SUMER.

In 2020 Bob published Snared, a novel based on his experiences with the armed people on grouse moors, and everything that goes on to produce a large surplus of birds to shoot. As we walk across the heather to the Field of Mosses and T47, a pair of plovers catch air, sing their jingle and drop back to the sedge. At home, Lydia and I see them arrive in late February, a busload from the coast in blingy gold outfits, like a hen party at Leeds-Bradford. These two are staycationers in elegant silver-grey winter plumage. They look rather like Ali, but I am 97.3% certain they are not vegetarians.

We are now on the Field of the Mosses, which, as far as moss goes, over-promises and under-delivers. I recall a similar disappointment in World of Leather. I look more closely and there is a lovely profusion of mosses working together. We fix T47 using the cold light of science: Bob has GPS and six-figure grid references; I wander about with ///what3words until it produces, I promise, ///lifted.fresh.grips. Ali has the OS app, which shows the tiniest paths, and makes my laminated OL21 look like the Mappa Mundi. On the other hand, you can insulate a sleeping bag from bare rock with a laminated OS Explorer, as I did on Sgurr nan Eag (‘skoo-err nan ayk’), the night before a solo Cuillin Ridge traverse.

Ali is keen that we head up to the Dove Stones and T58 for lunch. We yomp along for ages. When we get there, I refuse to look, as they are the most sensational thing in the whole nine square miles of CWF and have got to be fresh for another blog. I permit my staff to take the dreary snap below, purely for the record, as a petty official might document a bin shelter at the Taj Mahal.

Ali now reveals that she has a hard-boiled egg, and the reason for our arduous dogleg to T58 emerges. You could no more crack a hard-boiled egg on the Field of the Mosses than break into Fort Knox with a steamed parsnip, but here we are, sitting on the only rock in the grid square. She eats her smug egg without salt, in the manner of a stoat, and is installed favourite for Season 3 of The Traitors. We talk about peat, wind farms, the climate emergency, and gamekeepers we have known. Ali and I lay our tentative conclusions before Bob. He is immensely kind even though we are like a pair of A-level Physics candidates being given a viva by Niels Bohr. One of his current concerns is the management of Molinia grass monoculture. A tussocky grass moor isn’t a grouse moor and it isn’t blanket bog either. Dry grass is a cause of major fires, and the evidence is that Molinia tends to prosper where there is heather burning, and where the peat is dry. The strategy of the grouse moor owner is to flail the grass, poison the aftermath with glyphosate (which kills everything) and resow with heather seeds. It is expensive (and grouse moors are subsidized by us) isn’t really working to increase heather and tends to the opposite of blanket bog. When the moors are genuinely managed for carbon sequestration, it will be much more labour intensive; sphagnum must be planted in plugs, like Shane Warne’s strand-by-strand hair replacement, and the peat kept wet, with more than the token damming of a few grips. There is a fundamental conflict between managing for grouse and blanket bog, even though both wings hate Molinia. The Walshaw catchment management plan promises to deal with the tussocks, but Bob says there is not much sign of this taking place so far.

“To undertake the restoration, grass dominated ground will be sprayed with glyphosate by boom and lance, followed by a combination of burning, flailing and scarifying as appropriate to create opportunities for colonization by heath and bog species or to prepare a seedbed. The ground will then be seeded with heather, cotton grass and Sphagnum by air seeding, clay pellet, capsule or a suitable alternative method. Seed will be sourced through William Eyre and Sons, who are currently the sole supplier of such seeds or other suppliers as they come available. Where possible seed will be harvested on site.”

Bob favours hairy cows. We have a load of reading to do on this. Bob suggests we start with Moors for the Future and their FAQs on blanket bog management.

We head down, aiming for a higher crossing of Greave Clough at one of the fords; earlier we crossed the raging stream at the shooting box bridge. Considering that my companions’ boots must be completely sodden (I dubbined mine yesterday, and my socks have honestly never been drier) they spend quite some time trying not to get their feet wet. Three dots on my useless OL21 turn out to be a mighty lane through the peat, cut right down to bedrock. Were it chopped out four times wider, a 50m turbine blade could sai up it, no bother, and then come sadly back down again 25 years later, across a ruined moor. This lane is like a Dorset holloway, with heather for trees. You could film a remake of Rogue Male in it, with Hugh Grant squirming out of the peat having shot Major Quive-Smith (played, I fancy, by Richard Bannister) with (skip to the next paragraph now if you don’t know) a crossbow made from the rigid corpse of Asmodeus the cat.

Having summoned plovers, Bob now conjures a raptor into existence. We see it for five seconds, floating like a maglev train, inches above the heather. Female hen harrier, I hazard, but Bob, for whom evidence is sacred, can neither confirm nor deny the allegation.

Back at Clough Foot, we say farewell to the Wizard Berzins, who has manifested from Steel City to give us this amazing day. On our way back, Ali and I talk about the campaign. We reckon a complementary strategy to the bog argument is to engage with Mr Bannister’s love of land, folk and country, which we must assume is as great as our own. He is only drawn as cartoon villain Dastardly Dick Bannister in these blogs because he has a engaged a wacky consultant, Muttley, who with familiar self-sabotage has put turbine sites on top of the National Trust at Blake Dean, the ravishing Dove Stones, and Wuthering Heights, scattered at least 30 more like ‘Acme’ tacks over two-metre deep Natura 2000 blanket bog, and hung a sign saying GAS STATION on the track to the alligator swamp.

The real Richard Bannister is a countryman, integrated in a community where chivalry, love of neighbour and noblesse oblige remain the cardinal virtues. He is Master of the Pendle Forest & Craven Hunt, and his wife Ethne is churchwarden at St Peters, Coniston Cold. Richard Bannister’s friends and family will bring him home to himself again, and together we will restore the bog, with hairy cows and the hard labour of men and women in well-paid outdoor jobs, leading a thousand volunteers. When Coniston Hall is one with Nineveh and Tyre, the cotton grass on Walshaw Moor will still whisper “Bannister…Bannister…Bannister”. We are yet one nation.

I drop Ali in Hebden, which in hard winter sunshine is glamorous as Carcassonne or Dubrovnik. We resolve on another walk, in February, to T58 Dove Stones, where of course we have never been. It is difficult to make new friends past sixty, and today I have made two. Ali slips away like a hen harrier, and I wander into the Co-op, where some greedy bastard has eaten all the bacon rolls.

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Campaign news

Exactly thirty years ago in February 1993, a letter was published in the TLS against 44 wind turbines on Flaight Hill on the moors between Haworth and Halifax. On 15 February 2024 another letter has been published in the TLS against Calderdale Wind Farm, 65 huge wind turbines on Walshaw Moor between Haworth and Halifax, signed by hundreds of people at the intersection of art and ecology, including Mark Avery, Robert Macfarlane, Mark Cocker, Robbie Burton, Jonathan Elphick, Alys Fowler, Paul Evans, Prof. Mike Hulme, Lord Randall of Uxbridge, Paul Sterry, Alan Ayckbourn, Frieda Hughes, Sally Wainwright, Jeanette Winterson, Ian McMillan, Andrew Motion, Julie Hesmondhalgh, Patrick Gale, and Lynne Reid-Banks.

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

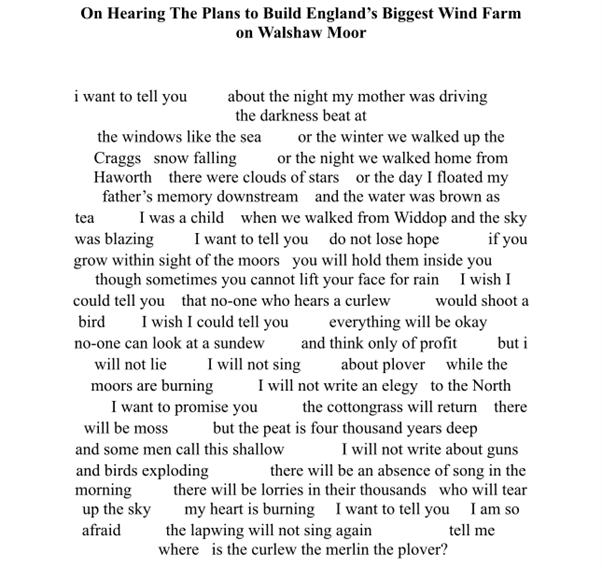

Clare Shaw was born in Burnley and lives on the hills above Hebden Bridge. Their fourth poetry 2022 collection Towards a General Theory of Love (Bloodaxe, 2022) won a Northern Writers’ Award and was a Poetry Society Book of the Year. They lecture at the University of Huddersfield, and run workshops with Wordsworth Grasmere, the Royal Literary Fund and the Arvon Foundation. From books to radio, community projects to international festivals, a faith in the transformative power of poetry is at the heart of Clare’s work.

This is the 3rd in a series of 65 guest blogs on each of the wind turbines which Richard Bannister plans to have erected on Walshaw Moor. Turbines 11 and 43 have already been described. To see all the published blogs – click here.

[registration_form]

Thanks for the shout out about the Carbon Calculator open letter and an amusing and informative blog post. Re hairy cattle, some of us from Hebden Bridge were given a great study trip on the RSPB’s Geltsdale reserve, where we learned that since the RSPB started managing Geltsdale, they have reduced sheep numbers considerably and have put in 150 cattle, which are free range. The results are encouraging. There is a lot of sphagnum spreading. Small shrub density is recovering (from a very low base, due to previous mismanagement), and a variegated habitat that is good for curlew has replaced sheep sward. They also found that although replacing sheep with cattle was first followed by molinia grass coming back, this was succeeded by lots of sphagnum of many varieties, and small shrubs such as crowberry. More info here https://energyroyd.org.uk/2019/04/no-burn-management-of-geltsdale-blanket-bog-and-heath-is-restoring-habitats-and-wildlife/

Amusing and awareness raising. Lessons in writing too.

Just a small correction: Ethne Bannister is Richard Bannister’s mother, not his wife. Richard is not Master of the Pendle Forest and Craven Harriers, but his father, Michael is joint Master with Richard’s brother Nick and Nick’s son Roddy.

Really enjoyed this. And have ordered Bobs novel. Can I subscribe to your blog?