Nick MacKinnon is a freelance teacher of Maths, English and Medieval History, and lives above Haworth, in the last inhabited house before Top Withens = Wuthering Heights. In 1992 he founded the successful Campaign to Save Radio 4 Long Wave while in plaster following a rock-climbing accident on Skye. His poem ‘The metric system’ won the 2013 Forward Prize. His topical verse and satire appears in the Spectator, and his puzzles and problems in the Sunday Times and American Mathematical Monthly. Email: nipmackinnon@gmail.com

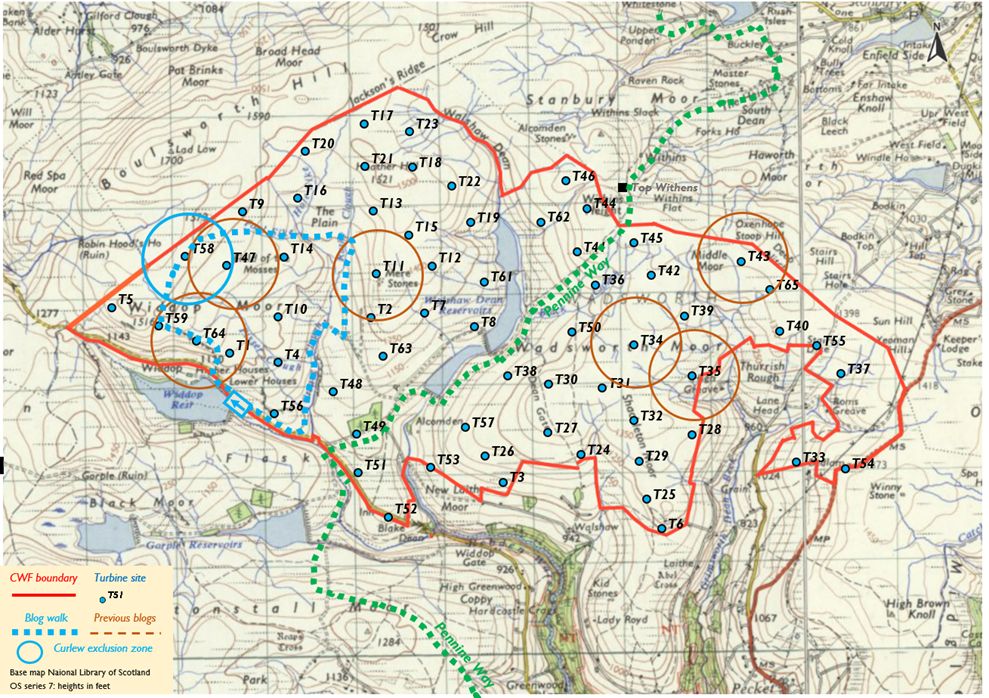

Turbine 58: Dove Stones SD 93290 34637, what3words ///eaten.rainy.dimension

By now, my modus operandi is clear to Hebden Bridge Neighbourhood Watch. “He parks in furthest space from Co-op, buys an egg & cress butty and a banana, and wolfs several bacon baps. At 9.55, between one and four women get into his Freelander and he drives them up moors. It in’t right. Summat ought to be done.”

Today it is Ali and her friends Stella and Sheila. I don’t know how I would otherwise have met these people: I bless the name of Bannister. Stella is cheerful because she has just paid a fiver for a towing-eye at a scrap yard in HB. It matches one she already had. I watch her put both lumps of stainless-steel back in her rucksack. I could say, “Stella, do please leave those heavy towing eyes in my boot.” Instead, I think, “Those’ll slow her down.” Stella explains that such eyes can be temporarily screwed into any car, allowing one to secure a sea-kayak fore and aft, and she wonders why I don’t know where these sockets are on my effete Harrogate tractor. She works with CROWS (Community Rights of Way Service) repairing the footpaths in Upper Calderdale and Ripponden. Click on the link and send them the price of a bacon bap or three.

If I was making this stuff up, literature students would one day write: “MacKinnon’s characters are deftly introduced with vivid establishing iconography: Bob finds a stoat trap; Stella brings a pair of towing eyes; Ali always carries an egg.” Sheila Tilmouth is a significant nature artist. Her vivid establishing iconography remains in her rucksack, for now.

I escape the valley with hardly any help, and we are soon at the Widdop reservoir car park, which is full of burly men with diggers, and will be until September. When we ask two of them what’s going on, they improvise the kind of Yorkshire knockabout that is a joy to anyone who moves here from the dreary south.

“We’re layin’ t’founds for one thousand new homes.”

“Oi! You tolt me ’twere a McDonalds.”

A supervisor comes over, seemingly to establish order among his minions, but in fact to demonstrate his consummate command of Lancastrian comic timing, bred in the bone, that reached its zenith with the late Eric Morecambe.

“We’re improving the reservoir. It’s…

[Eye-contact has drawn us in; two heartbeats pass, and now we enter those fathomless nanoseconds inhabited by Eric Morecombe’s genius]

…underperforming.”

A tipper lorry with twenty tonnes of yellowish ballast rumbles up the Widdop road at less than walking pace. It is viscerally heavy. Thousands of these loads will fan out from Cock Hill Swamp and pulverise forty kilometres of peat.

I fly park on the verge, and we set off up the desire path right of the Raven, with Ali setting a firm-but-fair pace. Once on top we walk along the sharp Scout edge. My companions know a lot about moss. There is less sphagnum than I thought, but more kinds of sphagnum than I knew. So intense is the bryology that Ali reports our speed on the OS Tracker as 1.3 mph, thus reducing her 2024 walking average to 11.4 mph. I have forgotten my waterproofs and am eager to get round before the downpour forecast for 15:20. In the meantime it is warm for mid-February. Grass is greening and the moor is much more awake than it was a fortnight ago. Later we will see a large flock of golden plovers, a female hen harrier stooping from glide to carpet hoover, and two fox moth caterpillars. Back at home in CWF-East, Diane Hazelgrove pointed out our first curlew on February 11, and the next day fifty lapwings arrived, like a shimmer of sea-glint against the far valley-side.

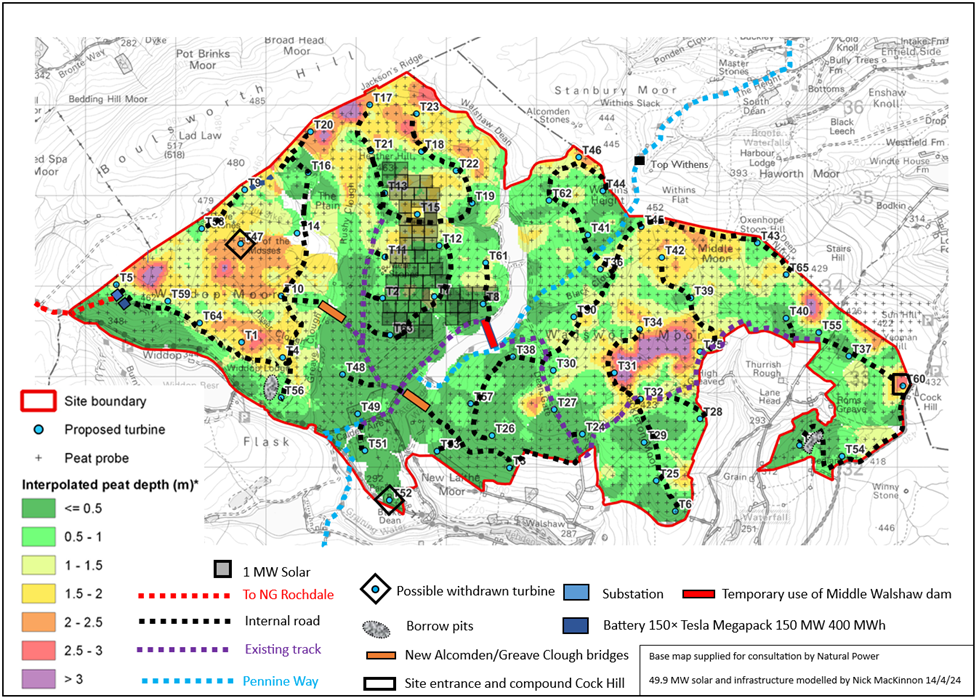

There is deep peat just a couple of steps from the rock edge. Muttley’s peat map shows this as dark green and less than 50 cm, but you can see it is at least a metre deep in the photo. A bare patch like this is rare on Walshaw Moor. Like his Hanna-Barbera avatar, Muttley must seem to support Dastardly Dick Bannister while actually undermining him. Were the peat degraded right across CWF then Muttley could say that it cannot get any worse, despite his 26 miles of roads, borrow pits, drains and turbine foundations. On the other hand, Muttley must not imply his employer is a reckless despoiler of habitat, bulldozer of roads the OS has never heard of, and eco-vandal of the first water. John Price went to prison for less. The truth is that Walshaw Moor is Ithilien, not Mordor. It has fallen under Sauron’s eye, and in places his orcs have dug deep pits and held savage feasts on man-flesh. The holloway cut down to boulder clay described in the T47 Field of the Mosses blog is an example. But the damage is reversible; fifty years of patient care and benign neglect will bring the bog back to glory. There is no comparison with Viking Shetland (a 103-turbine farm just completed), where four thousand years of grazing and a constant salt wind have stripped huge areas back to black. This link shows some shocking Shetland peat, but of course the photographs are by the developer; and the worse the peat seems, the better it is for the Muttleys. The truth about Walshaw Moor is that the great majority is very good for the West Riding, even though it does not compare with the best Lake District bogs. This is because of two hundred years of pollution, from which the moss is slowly recovering. CWF will set this recovery back forever. What there is left to restore after 30 years will not be the habitat we know now, which has taken thousands of years to develop, and is still getting over the Industrial Revolution, like so much of the north.

At Grey Stone Hill, where the sub-station and battery will be built on solid ground, we fan out to find the vestigial path across Crown Point Flat. Last time I was here, after Storm Isha, I said to myself, “I’m never walking across that.” But here we go. Muttley has put T47 Field of the Mosses in the middle of what I call “the Bannister Triangle”. I can’t go along with this absurdity any longer and have marked it as “Possible Withdrawn Turbine”, along with the one at T52 Blake Dean. The latter dummy turbine has been put in simply so it can be conceded in planning and make the National Trust feel they have done their bit. Rather than doing the hard yards on Muttley’s absurdly massive scoping proposal, as CPRE, RSPB, Ban-the-Burn and Calderdale and Bradford Councils did, the NT have “reserved their position”. The map below (informed at many points by Deep Stoat, my mole in the Bannister camp) shows an updated model of the potential infrastructure. The solar smudge shows what you need to get to 49.9 MW which is a maximum output. The average output of that vast mess will be 5 MW.

The Dove Stones are a lure, with the overhanging boulder and line of short cliff framing a secret. It comes quicker than you would believe. We climb down into a hollow between boulders, out of the wind. I spread my laminated OL21 and sit on my mittens.

So far, I have got away with a jumper and MAMIL leggings that were meant to be under Goretex trousers. I have wondered in the past if Muttley is going to grind the Dove Stones to aggregate for his roads, but after a recent trip to Bedlam Knoll, described next time, I no longer see the need.

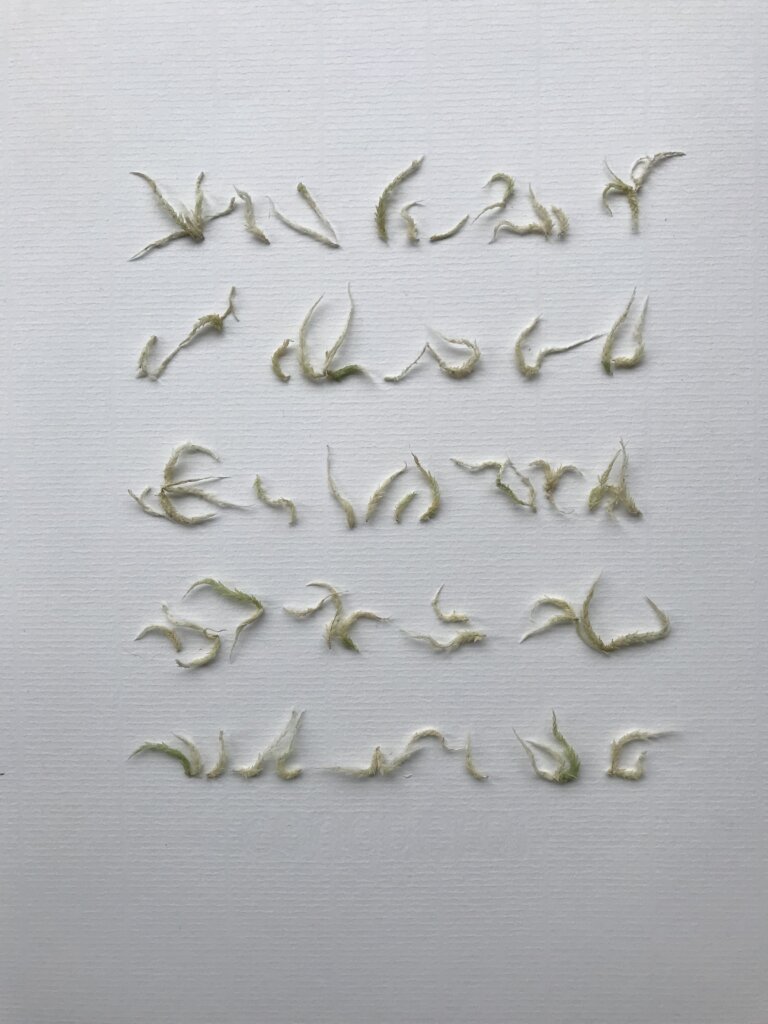

I produce my shy Co-op sandwich (is the cressy dampness a bug or a feature?) and a battered banana. From the groaning rucksacks of my companions a vast picnic emerges. Ali has an egg, of course, and thirty megatons of gritstone on which to crack it. She also has a Stoodley Swirl, bought on Hebden Market, that makes a Domino’s pizza look like a canape. Stella’s bagels were chosen from the sack carried by a 21st-century version of the muffin man who comes from down her way. “Dense … chewy … moreish…” Sheila adds to the groaning rock table her own entry in The Great Hebden Bake-off, and a tiny bag of herbage, which is not condiments foraged to season her repast, but clippings of moss and sedge which will very slowly become art in the strange region between her retinas and her engraver’s burin. Hugo Williams named this space the golden triangle of head, hand and eye.

We have broadly similar sensory equipment; what we train ourselves to do with the signals varies hugely. Musicians (Ali, Stella, or my son Duncan who made the sounds in Elite Dangerous) have drum-hammer-anvil-stirrup-cochlea; but the electrical patterns mean so much more to them. What is seen varies even more starkly. I knew Lucinda Chambers, lead stylist on Vogue three regimes back, well enough to ask her to talk to a theatre of students. Girls turned up in extraordinary gear: one came as a drum-majorette. Lucinda entered in a sack. “I always wear this. I’m a stylist, not a model.” [Audience sigh] “I go to the cinema, but there’s nothing on television for my eye.” [Sigh] “When I interview a girl for an internship, I always ask to see her scrapbooks, the thousand things she has really seen.” [Sigh].

We can all achieve a hundred-fold improvement in sight for a bit. Attend to a great painting for fifteen minutes; get as close to the paint as they’ll let you, but see it from other places, including the bench supplied. Many will pass, glance at the label saying, “Bathers at Asnières: oil on canvas: Georges Seurat 1884” and then delegate the signal processing to their mobile phone. You have noticed factory smoke on what felt like Sunday, the other child in the water is a hanger-on, and the teenager’s mum give him that haircut. You see Bathers a hundred times better than the people with phones, but artists see directly, without the words, all the time. They walk among us.

Stella enters the tactility of place, pointing out a bed-width overhang with a ring of fire-stained stones. It is then that I notice there is no litter. Unlike Muttley, the people who come here have a profound respect. Sheila talks about anthropology, the attuned-ness of remote peoples. I think, “But this gang of women are themselves an attuned tribe.” I feel the shortness of life with a pang: will sixty-five turbines be enough to unpack the anthropology of The People v Richard Bannister? I hug my fortune close.

Muttley’s tendency to make a fool of his client reaches its zenith at T58. (It is in fact nowhere near the zenith, as I found after my walk to Bedlam Knoll, next time.) An aerial view shows the way this imbecile turbine will defile this extraordinary place, creating the impression that Muttley’s employers Natural Power and Mr Bannister are vandals. What is the rest of their work like if they can be so aimless here?

As I wander round the turbine site the what3words Ouija board has messages for Dastardly Dick Bannister & Muttley: “disgraced.owns.universally” and “incisions.illogical.named”. For us, on our way to Lower Greave Clough it predicts “exploring.lowest.valley”. In a rare lapse into nonsense it blurts out “reclusive.hamsters.tent”.

We step across Foul Sike at its source and continue along the contour to a line of grouse butts. One way for CWF to cross the Greave Clough divide is by building a road over here, and this is what I modelled in my early maps. After walking here a few times, I no longer think this is viable and I now cross Greave Clough with a proper bridge much further south. The borrow pit in the rock at Slack Stones, which will supply the road system in CWF-W, then becomes available much earlier in the build.

These grouse butts are built for the traditional gun. Fettled dry stone walls are covered in six inches of scraped surface (the precious acrotelm) salvaged when the two-metre-deep peat was excavated.

The Balmoral look is ruined by the paving, or as Laurence Llewelyn-Bowen on Changing Butts would put it, “Dickie, Dickie! Love what Handy Andy has done with the Hanging Gardens of Baildon vibe, but the flooring, darling, the flooring!”

Why is Walshaw Moor the most demonised in England? Partly it is because so many people live below it and depend on it to protect and supply their livings, and they need it to be much more than an intensive grouse farm, even if they never set foot on it. I’m not going to demonise Walshaw Moor as it stands, because I cannot deny the evidence of my own eyes and ears. When I started going to the National Trust land in the dales, I expected to see even more than I see at home in Bannister country. I am no longer disappointed because I no longer expect to see much on NT land. I see and hear far more meadow pipits, skylarks, curlews, lapwings, plovers, cuckoos and stoats walking around the two mile track on Stanbury Moor in May than I see all day on National Trust property in the dales. Richard Bannister has lost patience and has paid Muttley to plan the industrialisation of a great wedge of moorland, and yet the National Trust are “reserving their position” on the proposal. Instead of agonising, the leadership of the National Trust should go for a four-hour walk in their dales in May, and then a four-hour walk in Bannister country, like the one in this blog. I don’t expect them to report on what they experience because it would be mortifying, but I do expect them to think about it. It is not too late for Walshaw, and a patient Bannister team can make this still glorious moor into a wonderland that will be a beacon for the South Pennines, and a model for a National Trust which has lost its way.

Upper Greave Clough has a footbridge, then we drop to yellow boulder clay in a deep Banny’s Grouseworld track, embellished with a naff carved stone at the literally dead end saying “2002”. It is a memorial to a period of intensification when the plan was to increase grouse numbers by a factor of ten. A mile later we cross Greave Clough again, at the sluice (SD 945 333). Here the fierce stream is intercepted and taken underground along the contour into “underperforming” Widdop reservoir. A permissive path takes us through the magical gorge that carries the overflow.

Lying on the path is a dead crow. It is crawling with tiny black flies, heirs to the maggots that must still be at work in the interior. A forensic entomologist could establish time of death.

Sheila says, “I want the skull.”

A wiggle shows that decomposition is not far enough advanced for immediate decapitation. From her rucksack, Sheila takes a Silent Witness kit: thin gloves, an evidence bag and a rubber band. She folds the bird up tenderly, like origami. It becomes unexpectedly small again. She drops it into the bag, pulls off the gloves and lets them fall in too, then crimps the lot shut with the rubber band.

It is not the first time she has done this.

Ali brings us back to the Widdop road at the Notch. She has led us along three charismatic icons of CWF: the Scout, Dove Stones and Lower Greave Clough. I drop my own three charismatic icons in the furthest space of the Co-op carpark. A curtain twitches in an upstairs window on Market Street. “Women returned seemingly unharmed. One has a dead crow in a plastic bag. It in’t right. Summat ought to be done.” nipmackinnon@gmail.com Artists and writers are encouraged to send their responses. Sheila Tilmouth is a Hebden Bridge-based artist working with the environment.

This is the 7th in a series of 65 guest blogs on each of the wind turbines which Richard Bannister plans to have erected on Walshaw Moor. Turbines 11, 34, 35, 43, 47 and 64 have already been described. To see all the blogs – click here.

[registration_form]

This could end up book sized, I hope. Don’t see the wind farm happening on that sacred bog, but glad others are more wary.

Beautifully written as always. That moor is more dreary than the ‘dreary south’.

Like many, I think of the Dovestones as a special place within the moor, and the thought of it being topped and surrounded by these monstrous things is profoundly depressing. Where will we be able to find solitude and contemplative space if this comes about? I have been thinking of moving back to the area from the south-east where I now live but am now waiting to see what happens here.

Your report of this walk also reminded me that, used as an edging stone in one of the culverts along the track in Greave Clough, is a date stone from one of the now demolished farms nearby inscribed ‘I S 1688’ . I do think that ought to be removed and kept safe.

Thanks for this fascinating series of walks and explanations.