Nick MacKinnon is a freelance teacher of Maths, English and Medieval History, and lives above Haworth, in the last inhabited house before Top Withens = Wuthering Heights. In 1992 he founded the successful Campaign to Save Radio 4 Long Wave while in plaster following a rock-climbing accident on Skye. His poem ‘The metric system’ won the 2013 Forward Prize. His topical verse and satire appears in the Spectator, and his puzzles and problems in the Sunday Times and American Mathematical Monthly. Email: nipmackinnon@gmail.com

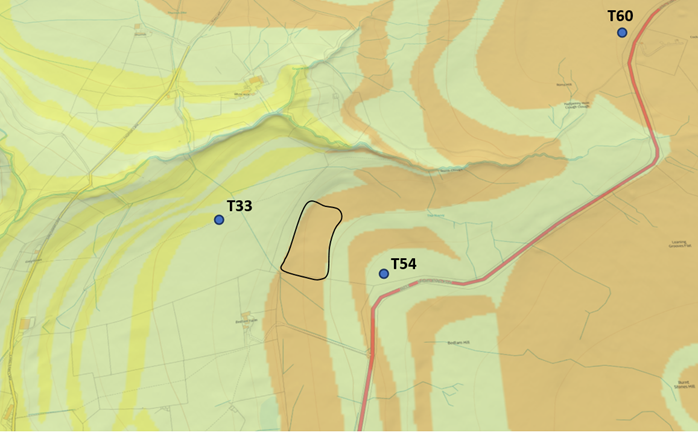

Turbine 54: Bedlam Knoll SE 00387 32119, what3words

///crabmeat.accusing.tuck

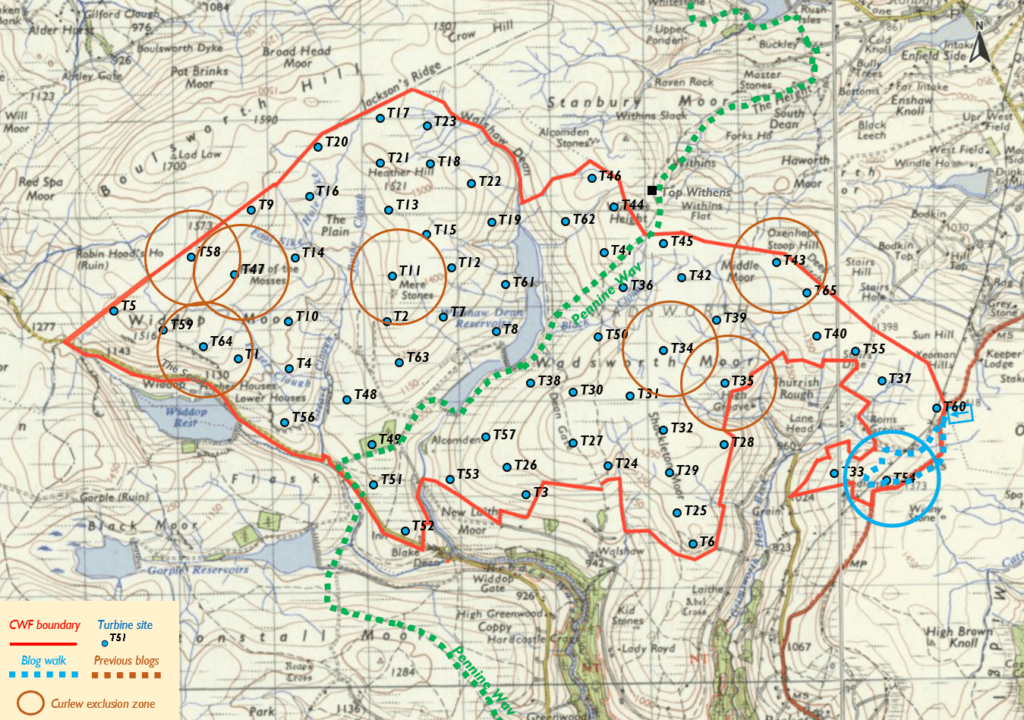

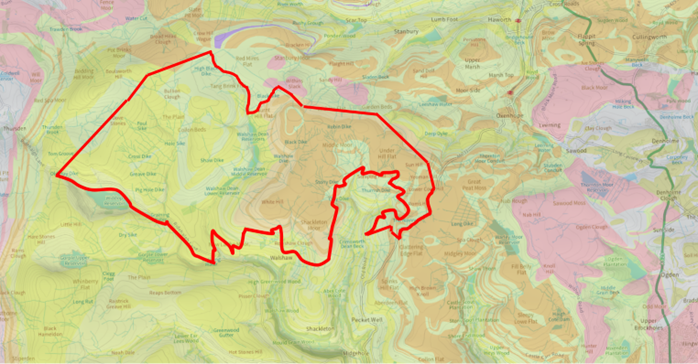

There is a mosaic of arguments against Calderdale Wind Farm (CWF). For me the intuitive arguments are to do with habitat, birds, and landscape, and as I do these walks by myself and with old and new friends, I find those intuitions are shared, and are based in the wonderful reality of this secret wedge of the South Pennines. In these blogs I am gradually unpacking the absurdly large scoping report, written by Muttley, Dastardly Dick Bannister’s consultant at Natural Power, in the light of what is up there. What I discovered after my walk to T54 Bedlam Knoll reveals a matter that will drain Mr Bannister’s residual confidence in his own consultants and will dismay his shadowy backers. (“Why did you not tell us about the aggregates, Richard?”)

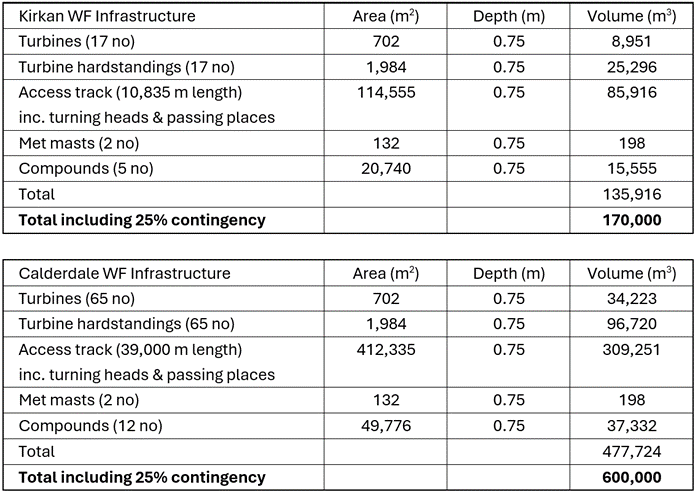

5 April 2024 You need a lot of crushed rock to build CWF – the access roads and turbine foundations are made of it. Most of these aggregates should be quarried from on-site ‘borrow pits’, because importing vast quantities from distance is ruinous for the electricity bill-payers who must service the mortgage, is grim for noise and air quality in the densely settled valleys and emits far more CO2 for everybody on Earth. We can get an idea of how much aggregate Calderdale Wind Farm needs by comparing it with Kirkan Wind Farm in sparsely settled Ross & Cromarty and allowing CWF some economies of scale.

The building method is well described in the Kirkan Borrow Pit proposal.

“It is anticipated that the initial section of track would be constructed with imported stone until the first of the internal borrow pit locations is reached. The turbine foundations, hardstanding areas and all access tracks after the first borrow pit are anticipated to be constructed using rock sources from site.”

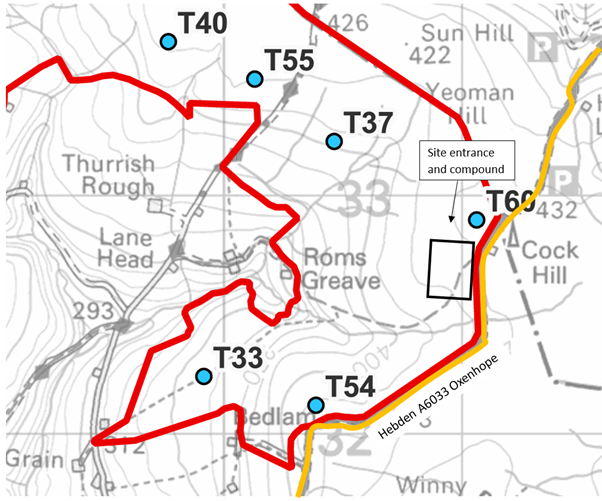

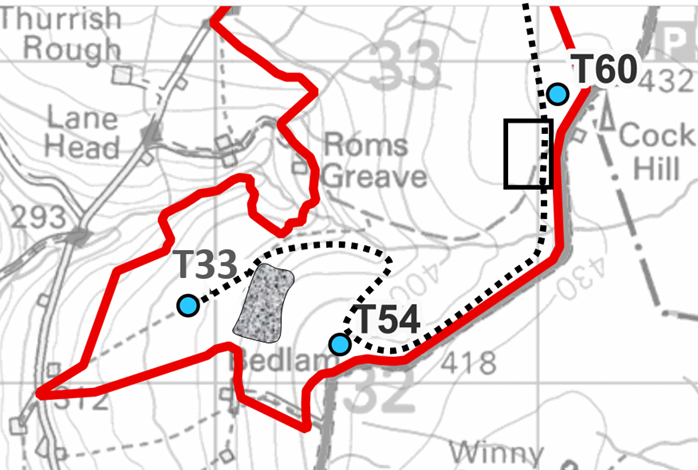

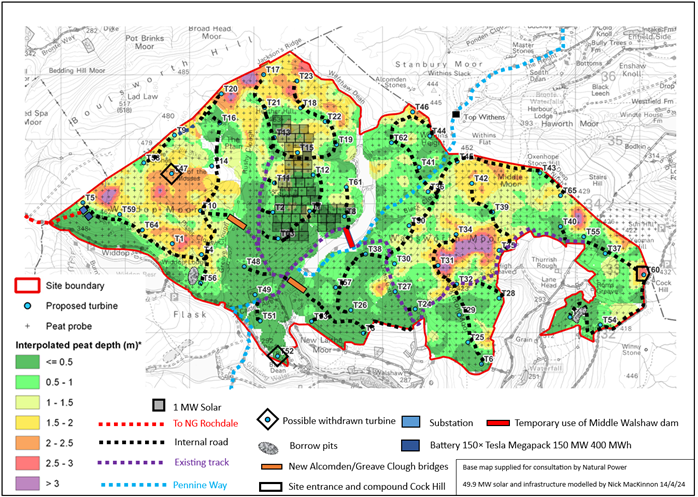

Muttley must open his first borrow pit as close as possible to the entrance on Cock Hill Swamp, to minimise the various costs of imported aggregates. The size of CWF then requires at least one more borrow pit in CWF-West, where, unlike the east end, there are plenty of named rock outcrops to crush. Today, I want to understand the awkward relationship of T54 Bedlam Knoll and T33 Grain Slack and find that first borrow pit. When I drew my first maps of the road system in CWF, I didn’t allow for the way Roms Clough cuts off T33 from the rest of the site. Muttley’s map shows the problem. Either he bridges the clough for the sake of one turbine, or he negotiates the direct route from T54 to T33 down the steep face of Bedlam Knoll, in part a 40% black run. The turbine manufacturers like the crushed rock roads to be at most 6%, and though 12% is allowed with a bigger insurance premium, you don’t snowboard a turbine blade down a black run. This is “The Mystery of T33.”

I park at the Cock Hill mast building on the Oxenhope to Hebden Bridge road. A rock (local gritstone formed 330 million years ago) marking the boundary was put here by the Oxenhope W.I. during the presidency of my mother-in-law. The site of T60 is as close as Muttley dares to this rock, which, like the monolith in 2001, has a message for him, and it isn’t OXENHOPE. Despite writing a 141-page scoping report, Muttley hasn’t said where the sole site entrance to CWF will be, but Deep Stoat, my posh mole in the Bannister camp, sent me a postcard in February: “Cable exits Widdop but sole site entrance opposite elephant. Pesto et pasta!” I don’t know why she (or is it he?) always signs off like this but there is only one elephant in Calderdale.

The track towards Roms Greave has been levelled down to the glacial boulder clay. It goes in the wrong direction to be useful to CWF, but the first bulldozer can come in this way and start scraping peat off Cock Hill Swamp, where a compound will be built of imported aggregate, 75 cm deep, pending the opening of the first borrow pit. I head down the track, because I’m never going to find a quarry site on this swamp.

In the photo taken at the edge of the track, you can see the active moss, sedge and grass, a layer of black shiny peat (Muttley’s expensive peat map puts it as 0.5-1 metre deep, which looks about right) and then the beginning of grey pebbly boulder clay, here spread perhaps a two metres deep like butter over flat gritstone by the last glacier. Muttley wants to crush the gritstone to aggregate, but first he needs a steep face, clear of peat and boulder clay, to get at it. Just east of the A6033 there are named stones (Winny, Burnt) and dozens of unnamed outcrops. On CWF there is no mapped outcrops (on the 1:25000) until you drop into Walshaw Dean where Dean, Grinnel, Deer and Hewer Stomes are named. West of Walshaw Dean there are plenty of named rock climbs for Muttley to blast apart. Until Deep Stoat’s postcard from deep in Bannister Country, I had the entrance to CWF at the western end where the substation and battery will be, because there is plenty of rock, even if the turbine blade access is impossible, either up the western Widdop road or through Hebden Bridge.

As I drop down the track, the clough on my left, which is nothing up at the road, develops steep sides. A muddy path cuts back into the charming clough, and I cross on some of Muttley’s gritstone, but it’s no use to him down here.

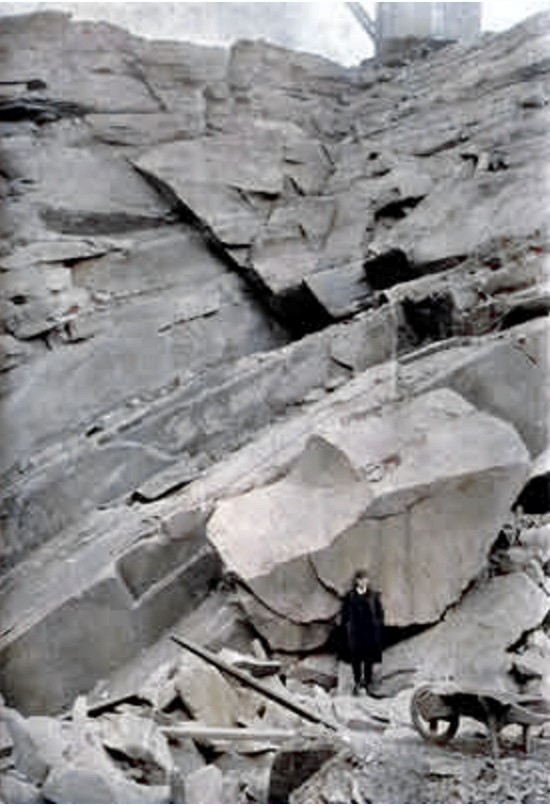

I climb back out of the clough and contour below Bedlam Knoll until I can see Bedlam Farm, neat, green, and walled off from the scruffy end of CWF. The sound of the A6033 is drowned by the racket of skylarks and meadow pipits. Walshaw Moor is a wonderland for ground-nesting birds, but this forgotten corner may be the best bit. A lapwing launches with its central-locking cry: “Pooweet! Wap-Wap. Pooweet!” Above me is the 40% face of Bedlam Knoll, and to my astonishment and glee, it is studded with rock outcrops that are not on any of the maps. It is far better than I expected. John Keats would have been thrilled to look into it too.

“Then felt I like some watcher of the skies

When a new planet swims into his ken;

Or like stout Muttley when with eagle eyes

He stared at Yorkshire grit – and all his men

Looked at each other with a wild surmise –

Silent, below a knoll in Calderdale.”

Here is the site of the first borrow pit, which in Muttley’s plan must be reached by road and blasted open before the rest of CWF can unfold out of it. The turf is only inches deep here, and this is the best quarry site I have seen, including the much rockier end above Widdop. I’m sorry about the inappropriate glee. I’m trying to unravel this wind farm by understanding it on the ground, and where the aggregates are coming from on Cock Hill Swamp has been a mystery since Deep Stoat told me about the elephant. Today the mysteries of the borrow pit and T33 have solved each other. A strong S-bend road will be built down to where the edge flattens into Grain Slack and the entrance to the borrow pit. A spur will later continue to T33 whose access comes free with the borrow pit.

I walk straight up the face, calves groaning, over the brow, and across tussocky grass to the site of T54 Bedlam Knoll, which is almost on the A6033. The site of T33 is now invisible below the brow, and the turbine will need the full 200-metre tip height to escape the shelter of the quarry face. I am still wondering if over-sheltered turbines have helicopter parents as I climb brutal barbed wire and plod back along the road towards Cock Hill. The cars zing by, and I repeatedly step off the road onto the sharp white aggregate that fills the drain.

As drawn on my map, Bedlam borrow pit covers 3 hectares, has an average depth of 10 metres and would supply up to 300,000 m3 of crushed rock, which is perhaps enough to build half of CWF. The S-bend will have to be the strongest road on the site because internal-use dumper trucks with a gross weight of over 50 tonnes will repeatedly grind up and down the curves, putting shear stress on the road as they brake or corner. These Bedlam bends will see ten thousand times more heavy traffic than a spur like the one to T33. We can think of the Bedlam bends as part of the spine of CWF. Another spine road goes north out of the Cock Hill Swamp compound towards the rest of the site and must carry 63 turbine pylons and 189 blades (only T54 and T33 get to turn left) and distribute all the stone that comes out of Bedlam borrow pit. Compare the simple layout at Ovenden Moor, with a single U of spine road, 2.5 km long, that had already been built for the 1993-2015 version (twenty-three 0.4 MW turbines) using plastic grid to float the limestone road over the peat, with 800 m of short spurs, built with more imported limestone, to just nine 2 MW turbines, one of which has been broken for months.

Mr Bannister’s choice of Cock Hill Swamp for the sole site entrance could not have been bettered. There is a flat expanse for the compound, yet a steep rocky face to quarry only 1500 metres away. OBL Aggregates are 16 km away, and can perhaps supply the 6750 m3 of aggregates that Muttley needs to build the road down to Bedlam borrow pit, after which the rest of the internal road system, the crane hard-standings and even the concrete for the turbine foundations, can perhaps use aggregates blasted, quarried, and crushed on-site, as at Kirkan. The turbine blade delivery has been proved to Ovenden Moor Wind Farm and from there a back door route leads to Cock Hill, avoiding Oxenhope and Hebden Bridge, with potential for a temporary shortcut that is as easy to build as any of the internal roads of CWF. There seems to be no physical barrier to CWF.

It is always darkest just before dawn.

In a country where so much seems to be privatised and failing, it is remarkable that you can look at the geology under any point you like, for nothing, at the British Geological Survey.

The brown stripe through the Bedlam borrow pit is East Carlton Grit, formed 321.5-320 million years ago. The green stripes are Millstone Grit (329-319 million years ago) and the yellow is Upper Kinderscout Grit (322-321.5 million years ago). All these rocks are Carboniferous sandstones, laid down in a vast river delta when West Yorkshire was at the equator. The desirable uniformity of stone in the Bedlam quarry suggests again that Muttley has been here before me. He just needed to take one more step and …

We come at last to the big surprise and I would never have discovered it without doing these walks and feeling the reality of CWF. The rough integrity and spectacular horizontal overhangs of South Pennine edges inspired and trained the working-class rock climbers who, in the 1970s, transferred their skill on gritstone to Annapurna South Face and ‘Everest the hard way’. Nevertheless, West Yorkshire imports most of its construction aggregates because crushed West Yorkshire sandstone is generally too weak and porous to be used for concrete or roadstone. My first inkling of this critical fact came from the explanatory notes on the map, which Muttley should have read too.

From BGS sheet 77 Huddersfield

“Sandstone is the principal mineral currently extracted in the district, and demand for this resource is likely to continue in the future. The sandstones are very resistant to attack by acid rainwater, and are attractive building stones suitable for walling, paving, and cladding. Coarse-grained sandstones (‘grits’) formerly worked for grindstones, pulpstones and millstones, are now worked for construction fill and for sand. In general, the sandstones are too weak, porous, and susceptible to frost damage for them to be used for good quality roadstone or concrete aggregate. They may be used in road construction below the level of possible frost damage and for some of the less demanding concrete applications.”

This weakness has been known for at least fifty years and applies to any aggregate won on CWF or quarried anywhere in Bradford or Calderdale. My mother-in-law’s boundary stone will last for a million years, but if you crushed it into aggregate to make a car port it would vanish in a week.

From Aggregates in Britain (1974)

“Carboniferous sandstones can be divided into two groups, depending on their strength. In north Devon and south Wales they are strong enough to make good-quality aggregates, whereas those in the Millstone Grit and Lower Coal Measures in Lancashire and Yorkshire tend to be too weak and porous to be used in concrete or as roadstones, other than for deep sub-base below the level of frost susceptibility. In northern England it is also a cheap local substitute for limestone and gravel aggregates, which would otherwise be imported over distances of some 60-100 km for such uses as filling for French drains, filter media and selected fill.”

About thirty cars a week use the informal car park below the walk from Stanbury to Top Withens, maintained by Bradford Met, enough to crater the surface. Even Dave, the fastest postman in the west, must slow down. Twice-yearly, a team from Bradford Met brings a tipper of brown aggregate and spends an afternoon conscientiously compacting it. For a week we enjoy a smooth ride and then it vanishes. Our neighbour says there are ‘voids leading to the centre of the earth’. The last time, the nice foreman said, “I’ve got hold of some limestone!” It stands firm, like a grey volcanic plug, while the rest of the carpark erodes around it. I hadn’t made the link with the subject of this blog until my wife Lydia was proof-reading and pointed out the obvious. The fugitive brown stuff was sandstone aggregate that had turned back into sand after 320 million years of minding its own business. A local builder wouldn’t use Muttley’s on-site aggregates to fill a curd tart.

The weakness and porosity of West Yorkshire sandstone aggregates is not a secret. The five councils, Bradford, Leeds, Calderdale, Wakefield, and Kirklees, publish an annual report on their aggregate problem, which is increasingly serious as the climate crisis makes everyone rightly reluctant to move stone by lorry.

From West Yorkshire Local Aggregate Assessment (2021)

“Executive summary: The majority of the construction aggregate produced in England and Wales was used for either concrete manufacture (31% in 2019) or road construction (25% in 2019). For geological reasons described in more detail elsewhere in this report, the mineral resources which are worked within West Yorkshire are generally thought to be incapable of producing significant quantities of the higher specification aggregates required for use in either road construction or concrete manufacture. Consequently, West Yorkshire will remain reliant upon the crushed rock aggregates produced in neighbouring authorities to meet most of its construction aggregate needs. The two principal sources for the crushed rock aggregates consumed within West Yorkshire are the Yorkshire Dales National Park and Derbyshire. Quarries from these two areas collectively provided for over two thirds of the crushed rock aggregates consumed within West Yorkshire in 2019.”

“1.2.6. Given its mineral resource limitations and heavily urbanised nature West Yorkshire is not able to independently meet the high aggregate consumption requirements of the modern construction industry, particularly in terms of concreting aggregate and roadstone.”

“2.2.2. The sandstones are too weak and porous for the manufacture of concrete or for road building and are commonly used in low specification situations and for bulk fill. However where investment is made in appropriate processing plant, these materials can be used to produce building sand, as well as a washed sand suitable for use in concrete products. These materials are used in large quantities in the manufacture of concrete walling and paving blocks at factories in Calderdale.”

“2.2.3. No sandstone quarry exists solely to produce aggregate within West Yorkshire; it is produced alongside the extraction of stone for the manufacture of natural stone for walling, cladding, and paving. At many sites the aggregate is essentially an occasional by-product and is produced in relatively small quantities for low grade uses.”

“3.4.6 Furthermore, as discussed more extensively elsewhere in this report, it must be acknowledged that the West Yorkshire aggregate reserve is predominated by material which is unlikely to be capable of meeting the specifications required for the two principal construction aggregate uses of concrete manufacture and road construction.”

From West Yorkshire Local Aggregate Assessment (2022)

“Key messages. The aggregate resource in West Yorkshire is limited. The geology of West Yorkshire means that indigenous supplies of high-quality land-won aggregate, for use in concrete and road building, are difficult, if not impossible to obtain.”

“1.2.3. Sandstone is quarried primarily for building stone; however, at many sites the wastage from the extraction of blocks and from sawing is crushed for aggregate. The sandstones are too weak and porous for the manufacture of concrete or for road building and are commonly used in low specification situations and for bulk fill.”

“2.4.3 At some quarry sites, especially in Calderdale and Bradford, the amount of aggregate product is insignificant. However relatively significant quantities of crushed sandstone aggregates are incorporated into artificial stone paving and walling products.”

“3.1.17. The fact that aggregate flows into West Yorkshire appear to be shifting to more distant supply areas is of some concern in terms of the increased environmental effects and climate change impacts associated with hauling minerals over longer distances. This places even more importance upon the need to facilitate aggregate haulage modal shift by investing in rail and waterway infrastructure upgrades and safeguarding rail depots and wharfs capable of offloading minerals in West Yorkshire. This has been promoted with some success in the Yorkshire Dales National Park.”

The West Yorkshire councils are so worried about the uselessness of the local aggregates that that they are investing in the canal network, but Muttley has failed to say a single word about any of this in 141 pages.

What does Muttley have to say about his aggregates?

“12.1. General construction traffic will consist of Heavy Goods Vehicles (HGVs), Light Goods Vehicles (LGVs) and cars. There are likely to be several route options from yet to be identified material supply centres (e.g., quarries). There are several quarries located to the east of the site which means depending on the site access and route the traffic will travel on the A629 before travelling on either the A6068, A646 and A671 and subsequently minor roads to the selected Site Entrance.”

Readers will (correctly) deduce that Deep Stoat gets his info from an advanced position in Bannister Country and not from Muttley in Glasgow, because these confused road choices imply a site entrance off the Widdop road at the west end of CWF, even though his quarries are to the east of the site. An example would be OBL Aggregates in Halifax, 11 miles from Cock Hill Swamp but at least 28 miles from a Widdop road site entrance via the A646 as suggested.

These nearby quarries to the east are on the carboniferous sandstone and supply high-quality building stone, not weak and porous aggregates for roads and concrete which nobody wants. There are quarries to the east that can supply quality road building aggregates, but they are not the ones Muttley is talking about. They are much further away, in the magnesian limestone belt that runs along the A1 through Knottingley 39 miles from Cock Hill Swamp and 57 miles if you insist on going through Hebden Bridge to some western site entrance.

Here’s Muttley again, saving the planet one borrow pit at a time.

“3.6. The Proposed Development would require crushed stone to construct new tracks and, where necessary, improve the existing tracks on site. The crushed stone will also be required to create the hardstanding areas for cranes and lay the foundations for turbines. Suitable volumes of stone and aggregate shall be sourced from onsite borrow pits. The utilisation of onsite borrow pits will assist with mitigating the potential environmental and transport network effects associated with transporting stone to the site. If surveys conclude that suitable sources of stone are available on site, the search areas for the borrow pits will be identified within the ES.”

That’s almost it for crushed rock in Muttley’s enormous scoping report, except that page 77 lovingly details a flake of flint found on Withins Height. The scoping report has 22 pages on Grade II listed buildings and not a single word about the aggregate problem in West Yorkshire. The CPRE observed the way Muttley inflates his scoping report with over a hundred pages of weak and porous fill. This inflation is an attempt to make it look as though Natural Power are experts in the local area, but they don’t even know that their aggregates are too weak to make roads, let along turbine foundation concrete.

The confusion about the quarry locations relative to the site entrance, and the utter ignorance about the weakness of Yorkshire’s sandstone aggregates shows that the geology in the report isn’t a conspiracy against the public to hide the limestone deliveries but is simple incompetence. Natural Power may have made Mr Bannister look like a doddery pensioner robbed of his life savings on Melinda Messenger’s Cowboy Builders. (“It’s a nightmare, Melinda. We’ve been left with half a megaton of weak and porous aggregates!”)

The scoping report should say that since Yorkshire sandstone produces aggregate that is too weak for roadstone or concrete, CWF will have to be built of up to 600,000 m3 of imported limestone aggregate, almost certainly from quarries north of Skipton, though there is also useable aggregate in the magnesian limestone band through Knottingley. Provided the site entrance is at Cock Hill Swamp as Mr Bannister and Deep Stoat say, rather than on the Widdop road as Muttley seems to think, the route from Knottingley is least disruptive, even though it is furthest. The annual outputs are Knottingley 270,000 m3, Swinden 1,500,000 m3, Horton 300,000 m3. The aggregate assessments observe that not all magnesian limestone is strong enough for road building or concrete either.

“2.4.3. Magnesian Limestone aggregates are generally found to be unsuitable to produce coated roadstone (asphalt) due to its insufficient resistance to polishing, with high specification road surfacing aggregate currently primarily supplied into West Yorkshire from quarries situated within the Yorkshire Dales National Park. However approximately 40% of Magnesian Limestone quarries are thought to capable of producing aggregates of sufficient strength to be used as a road sub-base or as a concrete aggregate.”

Just a word on geogrids, the 6-metre-wide plastic sheeting pieced with polygonal holes, used to build floating roads over peat. Some marginal aggregates might be stabilised by a geogrid sandwich, even if the road isn’t floating. The West Yorkshire sandstone aggregates are weak, not marginal, and a geogrid won’t work when the stone in the sandwich disintegrates to sand under even modest loads when it gets wet or frozen and is then washed out or blown away.

Muttley’s on-site aggregates won’t work and he’ll be casting around for limestone if he gets planning. CWF will need a lot of limestone in a short period, and the electricity bill payers are bound to be gouged on price, should the planners sanction the outrageous disturbance in the packed valleys of trucking limestone through narrow residential streets for years. The limestone quarries don’t need CWF as a customer; their resource is rare, and by train they can reach markets far away. The railway doesn’t help CWF because the nearest limestone depot is in Leeds, though it would be interesting to reopen the stone-handling capabilities of the heritage Worth Valley railway to Oxenhope (“Perks must be about it.” “Get off the line Bobby!” “Daddy! My daddy!”)

The density of limestone aggregate is 1.5 tonnes per cubic metre so 600,000 m3 will be brought in 45000 tipper trucks, each carrying 20 tonnes, and all of them must then go back empty. Assuming a Yorkshire Dales quarry, having skirted Skipton, they will pass the excellent Keighley Wetherspoons before they squeeze into the wrong lane because there are always three cars “unloading” outside European Foods, or negotiate the long tailbacks from the Toby Carvery to Keighley College and the railway station.

From here they grind up the Halifax Road, turn right at the mini-roundabout and swoop past Lees primary school where the zebra crossing is supervised by a lollipop lady, before turning left onto the Hebden Road corniche. If the residents don’t like these non-stop convoys, they can be blocked here by parking on both sides in a chicane. Straight across the mini-roundabout in Oxenhope, and drivers may stop at The Bay Horse for a well-earned 0.0, for with only the zig-zags to climb before they are finally free of terraced houses, traffic, parked cars and steep gradients they can get up to 40 mph for the first time since the Hard Ings roundabout outside Keighley. Five minutes later they are at the Elephant, where they will dump twenty tonnes of limestone (enough for three metres of track) in the compound, turn downhill empty and do it all again in reverse.

Swinden quarry is closest and largest, but it has a rail connection and so rightly has restrictions on export by lorry. I favour Heidelberg at Horton, well seen from Ingleborough summit, and perhaps you will favour it too, because the route to CWF passes Coniston Cold, where the Bannister family own a luxury hotel and spa. We’re all in this together.

Although the planning application is being handled by Calderdale, and they have been promised £75 million of electricity bill-payers’ money, if Muttley’s limestone comes from the north, the people most affected by the building of CWF will live in Bradford Met. Since CWF also ruins Haworth’s Brontë industry, I reckon another £75 million of our own money is owed to Keighley, Haworth and Oxenhope, and we mustn’t forget how Coniston Cold may suffer. (“They told me we’d be using our own rock, Melinda, but now it’s all trundling past the family sauna!”)

I think Muttley has no chance of getting CWF past the shadowy financiers, let alone the planners, if he can’t use the on-site rock for most of the 600,000 m3 requirement, yet Donegal tarmac scammers (“We’ve got a bit left over from building the M65”) would hesitate to use Muttley’s aggregates to lay a driveway in Colne. (“I need to get a 200 ton crane up it Melinda, but all five councils say my on-site aggregates wouldn’t stuff a samosa!”)

Muttley has a website on which he boasts: “Natural Power also provides expert advice and due diligence consultancy.” In his ludicrous scoping report this “diligent expert” details a flake of flint on Withins Height but fails to mention the well-known uselessness of 900,000 tonnes of his on-site rock. I advise Mr Bannister to sue Natural Power for the cost of the scoping report, for exposing him to public ridicule, and for trauma to his relationships with rich and powerful Saudi moneymen. (“What other surprises has Natural Power in store for us, Richard?”). I would love to be called as an expert witness, but the prosecution may prefer some glamour on the stand.

“Ms Messenger, can you confirm that this information on aggregates was widely available at the time of the scoping report?” “Well, it wasn’t spread all over page 3 of the Sun, but Mr Muttley is as capable of reading the annual West Yorkshire aggregate assessments as I am.”

“Sassin’ frassin’ Miss Messenger … .”

This is the 8th in a series of 65 guest blogs on each of the wind turbines which Richard Bannister plans to have erected on Walshaw Moor. Turbines 11, 34, 35, 43, 47, 58 and 64 have already been described. To see all the blogs – click here.

[registration_form]

A magnificent work Nick, I can vouch for the ineffectiveness of sandstone as an aggregate because when northern gas network ‘repaired’ our very quiet lane it turned to sand in a few days and it had to be dug out and replaced with limestone.

Dear Graeme. Thank you so much for this confirmation of the rapid deterioration of our local aggregates. It feels so counter-intuitive!

This is absolutely masterful. The development would also destroy Neolithic/Bronze Age rock art, standing stones and burials. The Mesolithic (the previous nomadic hunter gatherers) remains are of European significance. Mr Bannister has previously refused access for an excavation of a very possible Upper Paleolithic rock shelter (think prehistoric Eskimos – the first people to arrive as the last ice age was ending). Similarly, this would be of European significance and would be compromised/destroyed.

David – very interesting comment – thank you.

Calderdale Council Planning Dept’s Scoping Response requires the developers to carry out a palaeo-environmental assessment with scientific data and deposit modelling of the blanket bog, as part of the Environmental Statement. So I’m guessing this means the developers should identify the Neolithic/Bronze Age rock art, standing stones and burials and Mesolithic remains you mention, in their palaeo-environmental assessment?

Thrilled to read this David. Would you like to write about this in a turbine blog? Nick

Brilliant work. Thank you for your effort.

Thank you Lesley! Nick