Nick MacKinnon is a freelance teacher of Maths, English and Medieval History, and lives above Haworth, in the last inhabited house before Top Withens = Wuthering Heights. In 1992 he founded the successful Campaign to Save Radio 4 Long Wave while in plaster following a rock-climbing accident on Skye. His poem ‘The metric system’ won the 2013 Forward Prize. His topical verse and satire appears in the Spectator, and his puzzles and problems in the Sunday Times and American Mathematical Monthly. Email: nipmackinnon@gmail.com

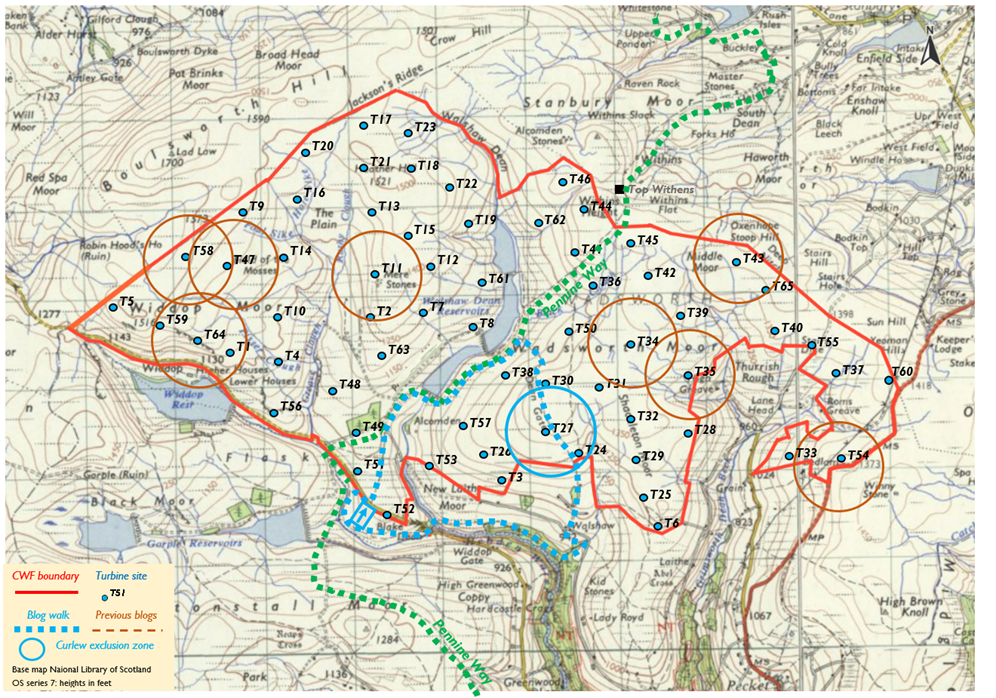

Turbine 27: Dean Gate SD 97196 32636, what3words ///crawling.held.dividers

24 February 2024 Today we are eighteen, which is the largest group I have ever walked in, and that’s not counting our leader, Foss the border collie. We have exactly the right number to stage King Lear, a play that is full of dog talk.

The plot involves an old landowner who wants to get shot of his grouse moor, and when daughter Cordelia won’t tell him sweet lies about how strong his aggregates are, he divides it between Goneril (Rigging Stones to Walshaw Dean) and Regan (Walshaw Dean to Cock Hill Swamp). Soon he is wandering the heather with his fool Muttley, howling for wind-generated electricity and the flooding of Hebden Bridge.

Blow, winds, and crack your cheeks! Rage! Blow!

You cataracts and hurricanoes, spout

Till you have drench’d our steeples, drown’d the cocks!

You sulphurous and thought-executing fires,

Vaunt-courtiers to oak-cleaving thunderbolts,

Singe my white head! (KL III.2.1-6)

As we set off from the Pack Horse Inn, I wonder how I can learn all the names in this dramatis personae, let alone invent glittering dialogue and complex personalities for them all. They walk on Thursdays, though not always in these Shakespearean numbers. Today’s mob (I am told often, and in an obviously agreed form of words) have been drawn here by love of this blog. Their real motive is dismay at the industrialisation of their moor. I start at the back where the naughty people are always found, and Cherril, a swordswoman, has already picked up a sheep skull. She secures this to her rucksack with the elastic laces on the back, thus finally solving the mystery of what they are for. She has been a bus driver. Ahead is ‘Soluble’ Dave, a soubriquet given him by his wife Gwyneth on the grounds that he never comes if there is the slightest danger of rain. Completely undermining this sensible approach to the outdoors, Dave is also a paraglider.

His academic work on software testing was spun out to Airbus, whose fly-by-wire A320 had software that really did need testing. Boeing pilots yanked analogue wires until 1992. Gwyneth was a freelance librarian. This oxymoron has no sooner been spoken then we arrive at the first dam. Lower Walshaw is brimming with oyster catchers, and on the far shore a huge flock of lapwings has got mixed up with a gang of starlings. Golden plovers also like to hang out with lapwings, who are much better at finding food than they are, but the plovers are much better at eating the food than the lapwings. Into this allegory of British politics comes a third party, the starlings, who are even better at exploiting the lapwings than the plovers are. Gwyneth worked for a year in Hanoi, where the technical libraries were all in French and Russian, with the Vietnamese now unable to read a word of either. She put their information service on a digital footing. So, both Dave and Gwyneth were spun out of academia into the hurly-burly and became exporters, doing their bit for the balance of payments.

This Thursday walking group is a terrific example of fresh air and camaraderie sustaining physical and mental health. Although their dynamic is notionally democratic, Ali has, like the Prime Minister of Vietnam, the musician’s gift of always being elected because we know what is good for us. On jury service, she would be foreman, and justice would be done or the sky falls. Beryl comes alongside; she worked with Home Start, a charity that helps children by supporting parents. She has travelled extensively in Transylvania with her husband Peter Riley and speaks Romanian. It seems a long way from her first job in Fenwicks. Carol is a retired family social worker, mainly in Bradford. She spoke fondly of the period from 1997 to 2010 when her work was properly funded under Sure Start and of how grim the post-2010 austerity has been.

The middle reservoir is almost empty, and the spillway from the upper reservoir is powering past it in a brown cascade. None of us knows why. This was an opportunity to see the neolithic stone circle that is normally under water, but I am too interested by Nigel, for we have lived, like Hitler and Stalin, parallel lives. He was born on the Central Line at Leyton; I was five stops down at Roding Valley. Our mothers were nurses and we lived in Hampshire (Winchester and Southampton) and both knew the Sunaks. I’m one of three (oldest adopted and met when I was 18) and he’s one of four: “Too many on my parents’ wages.” Nigel left school at 16 and went into the chemical industry. Then he became a driving instructor before “my friend’s girlfriend said I could join the civil service as I had five O-levels”. He worked on the superb GOV.UK interfaces that maintain one’s belief that the excellence of the British state is, like King Arthur, asleep under the hill, despite the political leadership. A 16-year-old school-leaver cannot have Nigel’s career now, and that means something has gone terribly wrong with our society. Something has also gone terribly wrong with our politics. At school we learned the three worst Prime Ministers:

3: Anthony Eden, ten of whose cabinet went with him to Eton before they invaded Suez.

2: Lord North, another Eton alumnus who delegated the American war to the Earl of Sandwich.

1: the Duke of Grafton (Westminster like Clegg) who had sex at the opera with Nancy Parsons

Pluto is no longer a planet, the brontosaurus is no longer a dinosaur and the three worst PMs have been relegated by 3: Theresa May, 2: Boris Johnson, 1: Liz Truss. No child will ever again learn what a Prime Minister can accomplish during Act 2 of La Clemenza di Tito.

I hit the front where Ginny, the oldest at 80, is setting the blistering pace. Like Stella, Ginny is a Crow who mends the paths in Calderdale, though not this Bannister Country road on White Hill. “They call me the drainage Queen,” she says, and Stella confirms that no ditch is delved nor grip grappled without Ginny’s advice. Pam the architect takes me up the steep bit of White Hill. When I say that we are strung out like a Himalayan trek, she tells of taking her sons out of school for a term and going to Nepal to see Mount Everest. “It was an easy decision because the headteacher was so foul.” She has retained the sunniest of outlooks despite the complex problems we face. “I’m an optimist, except about the future” she finds herself saying. I drop off the pace to find Ian (IT, starting at Heriot Watt in the punched-card era; he is a kayaker) a fellow Scot who has retained his take-it-anywhere accent despite living away for decades. “However you got it, if you have it at 7, you keep it.” I was gifted mine at 10 and crowned ‘sexiest voice in college’ by a woman who would become Home Secretary under Tony Blair, but all I have left is an RP that might be useful for Flake voiceovers. People assume I am the love-child of Stephen Fry and our late Queen. Ian’s accent is welcome at the ambassador’s parties, as a cameo in Trainspotting III, and in the delivery of humorous farewell speeches to justifiably dismissed colleagues.

Just before lunch I meet Pete who is a mountain leader. “Glen More Lodge?” I hazard. He nods grimly and we need say no more about the rigours he faced: GML has the same fearsome cachet as “the Falaise Pocket” or “the grain elevator in Stalingrad”. His wife Dorothy sits down with watercolours and does a rapid painting of our lunch spot at T27, full of light and energy. Our what3words position is ///crawling.held.dividers, a crisp summary of Muttley’s servile work on the Peat Map. One by one the group visit this 3×3 metre square and pay their urgent respects to Mr Bannister’s turbine site. Foss looks on aghast.

She has been trained not to scrounge sandwiches and when reminded of this social contract, gives Mo a big lick to show there are no hard feelings. Foss is 13 and Mo says she is a bit tired, as well she might be at 91 dog tears. This long loving bond between Mo and Foss is a bit heart-breaking as we lost our bedlington Pixie recently; she would have had no self-control among the picnics. I am invited to rally the troops with a rousing speech against the wind farm. I say, “Even though CWF is an assault on deeply protected habitats, isn’t remotely as green as the developers claim, will not reduce bills, is an opportunistic scam, won’t make much electricity and is an insult to the north, it’s going to be much harder to stop than anyone thinks, especially in the rush of excitement of a new Labour government, keen to prove that they are pro-growth.” This “nothing to offer you but blood, sweat and turbines” stuff lands badly and I return to the back of the class for the drop down to Walshaw Lodge, last bastion of the Savile Estate.

Here a disagreement about the best way to reach the old railway is resolved with hardly any bloodshed, and after this velvet revolution we cut through lovely Over Wood. The ease with which Pam manages the soft steep path brings my Day of the Leki Poles twenty-four hours closer. I get down like Gollum. The river is going like an express train. Alcomden Water finds Graining Water at a footbridge and raindrops, who, like rocket scientists in 1945, had to choose east or west on Jackson’s Ridge, are reunited at one of Yorkshire’s finest picnic spots. Other raindrops opted for north and Lancashire, and will be evaporated before they see Mytholmroyd again.

The rain that falls on the Walshaw catchment reaches Hebden Bridge via Greave Clough, Walshaw Dean or Crimsworth Dean. The fact that the first two are intercepted by reservoirs does little to save Hebden from a huge downpour in winter, when the sluice in Greave Clough is at capacity and the spillways in Walshaw Dean must save the dams from being over-topped. The idea that peat is an ever-absorbing sponge is wrong: ideally it is already saturated and it certainly is in winter. Saving HB from flooding isn’t about water storage in peat and reservoirs: both will already be full, no matter how extensive they are. A catastrophic downpour travels on the surface, and it is here that slowing the flow works, by blocking the grips and restoring vegetation to increase friction, especially in gullies that are down to bare peat or bedrock, and on clough-sides. At Hardcastle Crags, hundreds of leaky wood dams have been built, nearly all by volunteers, some of them also creating larger areas of temporary water storage, and these have been shown to reduce the peak flow that triggers the siren and overwhelms Hebden Bridge. If simple interventions have a measurable effect, then the complex CWF intervention is certain to be a step-change. The turbine foundations and crane pads, the roads cable ducts and associated drainage, will inevitably speed the flow of water off Walshaw Moor.

This massive industrialisation of the catchment is wholly out of proportion with recent measures taken by Slow the Flow and the Environment Agency, who have been mitigating the consequences of over-enthusiastic grouse moor management. Muttley will claim a ‘minimal’ increased probability of a catastrophic flood. In that case he should have no problem insuring the ‘minimal’ flood risks, but we know there is no chance of his putting his money where his mouth is. The developers only want the upside: a cocktail straw stuck in the electricity bill of everyone in the UK, up which they will take their steady suck, whether or not the wind is blowing, whether or not their electricity is wanted that minute. Council taxpayers, building owners and electricity users must cover all the CWF externalities, and one of the largest of those items is the increased frequency of catastrophe in the Calder valley.

The last leg of what Foss and I think has been quite a long march, is along Ridge Scout, the north edge of the treeless dale-within-the-dale that holds Graining Water. Here I take up with Sue the singer, who stands up when she plays the banjo, appears to be in her late 30s, and is a step-great-grandmother; and Moya, who is named after a song that was popular at her conception. I wondered if a similar surge in ‘Nigel’ and ‘Eileen’ was occasioned by XTC and Dexys Midnight Runners, the fruits of which would now be 45 and 42. We thought Eileen maybe and Nigel not so much. His curve (found on a GOV.UK site maybe powered by our own Nigel) peaked in 1964 at 22nd and was still a respectable 55th in 1979 when “We’re only making plans for Nigel” was released. The parabola has a blob at this point like a bluebottle has died on the screen, and Nigel vanishes forever. Eileen has never been popular enough to feature in the ONS top 100, but there is a fun site hosted by Time Magazine which notes a classic year for Eileen in 1982 when Come on Eileen was number 1 in the Billboard charts. Moya has blue hair and admits that she has never read this blog. Hi Moya!

Ali has rung the Pack Horse and they have opened half-an-hour early for us. It is a fantastic pub with great beer and a hundred single malts. I think it is Sue who has the first half and half I’ve seen ordered since I left Dumbarton aged 17, though that was MacEwan’s Heavy & Bell’s and this is Goose Eye & Scapa. I bag my last, Claire. It’s a small world and it turns out we’ve already met on Arran in 2013 when I was picking up a prize for ‘Starling’ (they make human noises decades after the humans have gone) in the McLellan poetry competition she ran with her husband David, whom I also recently met again at the memorial for John Foggin. We both go a bit misty eyed about Glen Sannox.

Stella, just back from the Menai Straits with her kayak secured to her towin’ eyes, buys me a pint, and says the nicest thing in the gruffest voice that anyone has said to me for years. “I’ll get this. You’re enhancing my life.”

This is the 9th in a series of 65 guest blogs on each of the wind turbines which Richard Bannister plans to have erected on Walshaw Moor. Turbines 11, 34, 35, 43, 47, 54, 58 and 64 have already been described. To see all the blogs – click here.

[registration_form]

Moya? Moya is also appears as a living Leviathan spaceship in the series “Farscape”, capable of things called ‘starbursts’, powering around the universe under her own steam (so to speak).

What wondrous writing, wringing humour from this situation, well done x