Nick MacKinnon is a freelance teacher of Maths, English and Medieval History, and lives above Haworth, in the last inhabited house before Top Withens = Wuthering Heights. In 1992 he founded the successful Campaign to Save Radio 4 Long Wave while in plaster following a rock-climbing accident on Skye. His poem ‘The metric system’ won the 2013 Forward Prize. His topical verse and satire appears in the Spectator, and his puzzles and problems in the Sunday Times and American Mathematical Monthly. Email: nipmackinnon@gmail.com

Turbine 5: Grey Stone Hill SD 92342 34015, what3words ///poorly.dated.mills

29 February 2024 I’m back in the far corner of Hebden Bridge Co-op car park. A tramp, smoking a crumpled roll-up like George Orwell in ‘Down and Out in Paris and London’, watches cynically as artists board the Freelander. Louise Crosby is a poet, illustrator and zinester. Sheila Tilmouth we last met doing ‘Silent Witness’ with a crow in Greave Clough. Lou and I have been teachers for seven decades between us. She did Everest the Hard Way, with Geography in Calderdale and Rochdale. Rejected for teacher training, I did mine at chalky Winchester, where I looked after Momentum founder James Schneider and taught Rishi Sunak. As I write, they average out to Angela Rayner, but if the Prime Minister keeps jogging after the Reform vote, by publication they will straddle Margaret Thatcher.

At 9.55 Ali and Stella come by as though by accident. Stella has a bag of empty containers which she is going to fill with muesli, baked beans, and washing-up liquid, because she has achieved escape velocity from the consumer culture. Sheila shows us her ruck sack, which is also full of empty containers. There is no telling what will end up in these, but it won’t be muesli.

“We just need Johnny Turner now.”

The tramp takes a last punishing draw on his cigarette and says something along the lines of, “I am Aragorn, son of Arathorn, the heir of Isildur. Here is the sword that was broken. Will you aid me or thwart me? Choose swiftly!”

The people I meet on these walks strike me as more extraordinary than I feel at liberty to unpack, given that they are civilians, and this is ‘Come to Bannister Country’ not ‘Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil’. Were Muttley found in a grouse butt, kebabbed like Edward II on a three-metre peat probe, the authorial kid gloves would come off presto pronto. That said, Johnny Turner in his element is quite something, so…

He has masses of grey hair swept back like Gianni Agnelli in his prime. (“Fiat must have an odd number of directors, and three is too many.”) It stays there by morphic resonance: no chemicals were used in the making of this barnet. He is a bryologist, a moss expert, and made his living at it, but found it kept him away from home for weeks, so now he is a freelance gardener. From cotton jacket to dancing shoes, he is radically under-equipped for our walk, except that round his neck is a jeweller’s loupe through which he will identify sphagnum like Geoffrey Munn reading the hallmarks on ‘Antiques Roadshow’.

If Johnny Turner made ‘Moss: the Secret Garden’ it would be as though Monty Don had hybridised with Mick Jagger. The fan mail would make the foyer of Broadcasting House look like Hallmark Cards in early February.

I park at the end of the track that runs parallel to the arrow point of CWF, up to the failed oil well. This bypasses the rocky front of the ridge along Widdop and would be a back door into the wind farm were it Bannister owned. Sheep are gossiping by the clamp like a wedding congregation waiting for the Queen of Sheba. The track’s foundations of concrete lumps, paving slabs and shattered Belfast sinks leach variety into the soil chemistry. These in-between places are rich in species, so Johnny is already bent double like a giraffe at the waterhole. For the next four hours, unless I say otherwise, Johnny is bent double like a giraffe at the waterhole. Sheila knows moss too, but it is Lou who also has her head in the bog when the farmer drives up the track. He may think they are examining a dead sheep.

There is a maxim in economics that you never find a £10 note in the street because somebody else will already have picked it up. Similarly, you don’t come across a dead sheep when out with Sheila Tilmouth, because it will already be in the Tupperware boxes in her rucksack. I walk back gloomily to where she is talking to the farmer, expecting to be told off for fly-parking. In fact, I’m in for a dissertation in perfect paragraphs, initially coaxed by Sheila and then coming in a glorious flood, from somebody even deeper immersed in their element than Johnny Turner.

Graham Bancroft’s grandfather married into the land west of CWF in 1947. As I arrive at his tractor, he is being satirical about what various ecologists have told him to do. “They make a mistake, and they can swan off to their next posts. I have to live with it for the rest of my life. They tell us not to burn the dead grass but the last one who told me that had charge of Saddleworth Moor for nine years and then the whole lot burned deep into the peat. A thousand years went up in a week. Didn’t matter to him because he’s been promoted. When I burn, it just flashes off the dead grass like having your ears done at Turkish barber. We had three thousand sheep and a hundred cattle on here and they told us to go down to a thousand sheep and no cattle, so we did, and we got EU payments. Now we keep doing it even though there’s no payments because we think it’s right for the land. Now they tell us they want cattle back again because they graze the molinia, which is what we’d told them before ours went to Skipton.”

Sheila asks what he thinks about CWF. “Well, you’ve got to build wind farms”, he says briskly and tells us about the way his grandfather got going in the hungry years after the war. I take this as Graham’s final position, but Sheila knows there is more, and Paxman-like, she finds a way to ask the question again, twenty minutes later. “They will come here and build their wind farm and then we’ll never see them again and the land will just go to ruin.” His eyes are wet. Sheila taps the seat of the tractor in sympathy. I hate this moronic wind farm, but Graham Bancroft’s sadness goes down to gritstone. His family has loved this land for decades.

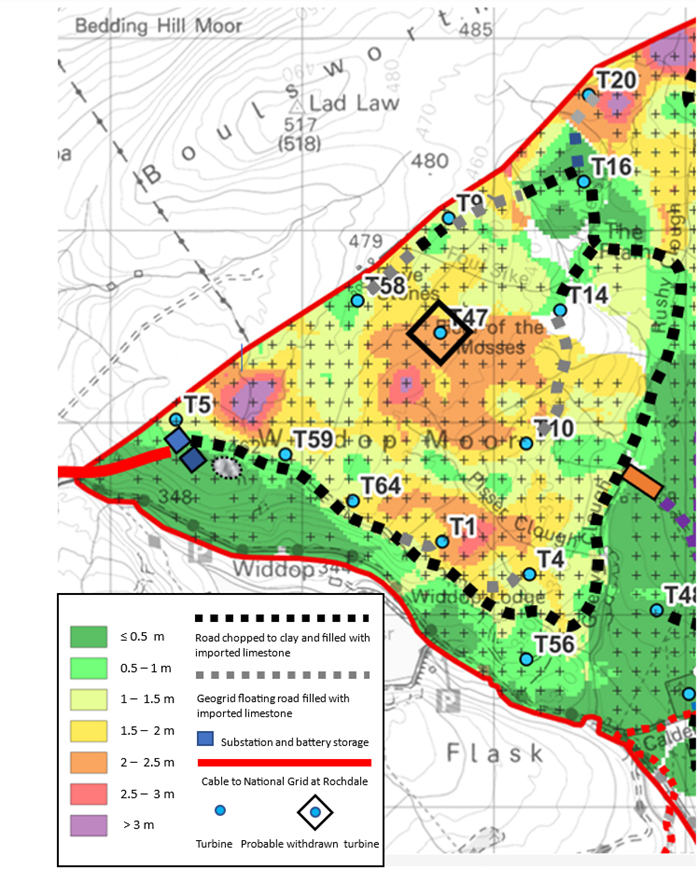

At the top of the track, we turn right along Tom Groove into Bannister Country. Navigating west of Greave Clough with a laminated OL21 is like tickling a gnat’s arse with a telegraph pole (as one of Orwell’s tramps puts it in ‘Hop-Picking Diary’) and if we seem to be getting anywhere it is because Lou has the OS app and isn’t afraid to use it. Everybody else is hot for moss, but I want a plausible site for a 132 kV substation and 150 MW battery. I now know for certain that they aren’t down here on Crown Point Flat, because it could eat a Tesla Megapack for elevenses, like a Mr Kipling individual Battenberg. All the electrical infrastructure in the Bannister Triangle will have to go on Grey Stone Hill next to T5. Any road built across ground like Crown Point Flat has to float.

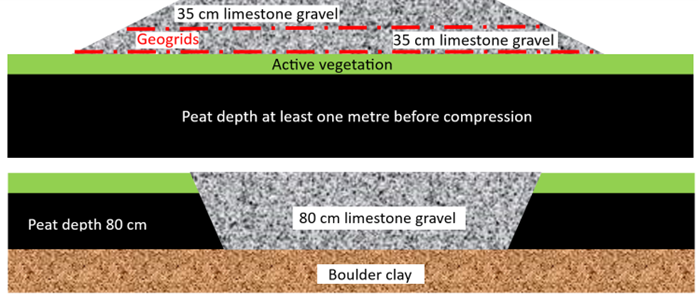

Floating roads are built on peat that is at least one metre deep. A perforated plastic geogrid is laid down on top of the peat to stabilise the aggregate above, which locks into grid. In shallower peat, a trench is cut down to the boulder clay and filled with crushed limestone, or aggregate is dumped until the peat is displaced sideways. In the Bedlam Knoll blog, it is shown that the on-site sandstone rock cannot be crushed to usable aggregate, because it is too weak and porous, and susceptible to frost. The limestone must be imported from fifty miles away in forty-five thousand tipper loads. There need not be many floating roads on CWF, and none if a dozen turbines are taken out, like T47 Field of Mosses. Floating roads, like borrow pits, are sold as “better for the environment” but mainly they are better for the developer, minimising the cost of aggregate and peat transport. Compressed peat under a floating road forms a dam which dries out the bog downhill, releasing a vast plume of sequestered carbon.

We set off across unplumbed purple-depth peat towards T5. Lou is in the lead, looking for places where we won’t sink up to our navels. I wander between Lou’s version of ‘It’s a Knockout’ and the feature-length episode of ‘Moss: the Secret Garden’ that Johnny and Sheila are presenting. It’s a bit like ‘Fake or Fortune’ with Philip Mould and Fiona Bruce, whose intro has Mould saying portentously, “Science can see beyond the human eye”, a catchphrase in our house and maybe in yours. Instead of mass spectrometers and dendrochronology we have a jeweller’s loupe.

“Look, Sheila, this is Sphagnum cuspidatum.”

“It looks very like S. fallax from here.”

“Yes, it does, but it’s the terrestrial form. If you see it in a bog pool it looks like a drowned kitten, but this is adapted to a more variable water table. The curved branch tip is conclusive.”

Johnny continues to move across the uncertain surface with his head between his shoes.

They are now on a red patch, like the Martian weed in ‘The War of the Worlds’. “Is this S. subnitens or rubellum?” Sheila wonders.

Her co-host picks a bit and snaps to vertical to use the loupe, though he has already made the subnitens/rubellum call on the gestalt that birdwatchers and bryologists call ‘the jizz’, an ability anatomised in Malcolm Gladwell’s ‘Blink!’.

“It’s more top heavy than the rubellum which we saw earlier, and that was red, but this is brick red.”

“When you get it home subnitens has a silvery sheen, like a cocktail dress.”

“That lustrousness when dry is conclusive for subnitens, but in the field I go by the shagginess of the fascicles just below the capitulum.”

I love it when they talk mossy.

They stand in front of a pinkish hummock. “Sphagnum russowii. Classic habitat facing northwest in heather-dominated ground. Doesn’t mind a sniff of nitrogen, a bit of flushing.”

I think I have the jizz too and point out a patch of something that I’m pretty sure is sphagnum. “S. auriculatum, see the cow horns? It’s the commonest species, but when it’s robust like this you can confuse it with the palustre we found earlier.” He snaps the stem and squeezes out the water to examine the cell structure. “Palustre has a much wider cortex than auriculatum.”

After leaping two mires in which she might have disappeared like the demon king in a pantomime, Lou has found a way off the Bannister Triangle, where fully crewed substations can sink with all hands. As soon as the going is firmer, Johnny snaps out of ‘Oppenheimer at Los Alamos’ mode, lights a here’s-one-I-made-earlier that is the only dry thing in our grid square, and says, “Sorry to have given it such a sketchy once over. It’s a good bog for round here. Cattle grazing and burning the dead grass will help. The best Cumbrian bogs didn’t catch the sulphur dioxide from the cotton mills that this one got on the westerlies. It will be another two hundred years before it really recovers, but it’s a great bog for West Yorkshire. There are some leafy liverworts I’d expect to find in a bog as good as this, but they aren‘t here yet. When you find them, maybe in a thousand years, you’ll know the bog is fully back to itself. Perhaps they’re here already, but I need a month, not four hours.”

Here was the awesome leap between tiny and vast, the quick and the dead, life’s brief candle and deep time: ruby-celled microcosm in the jeweller’s loupe and the macrocosmic hugeness of Crown Point Flat, soaking up the industrial revolution’s acid rain and refossilising the carbon. And what unexpected agreement between Turner and Bancroft on vegetation management!

We find Lou in a private universe of hair moss where she is taking photograph of the day.

We head for the tallest feature in the landscape. It turns out to be a bird-seeded rhododendron, scion of the bushes that once screened Lord Savile from his tenantry, which Yorkshire Water have been arduously removing from around what were once our reservoirs in Walshaw Dean.

This escapee reminds me of the velociraptors on the supply ship at the end of ‘Jurassic Park’. By the monster at Lower Laithe reservoir in Stanbury, YW have put a sign that says, “Caution! Keep Clear. This Plant is Invasive.”

Looking over to Pendle, Lou remarks that her boots are saturated, and remembers a very different day walking up here in June 2012, and finding them full of dust instead. “Later it didn’t seem a surprise when we had the flash flood.”

We cut down to the track. I feel my heart lift as we leave doomed Bannister Country and enter a domain where Graham Bancroft is God to a thousand sheep. Back at the car, there is no escaping the Burnley end of the Widdop road. Never mind bringing a turbine blade up here; you can’t even turn a car round for a mile, except end-over-end down Rapes Hole.

Lou hasn’t had enough action yet and jumps out of the Freelander at the Blake Dean zigzags to squelch home. As we drop through Lee Wood, Sheila talks about her plans for the next few months and Johnny hopes his gardening work will pick up now February is done. We drop him at Hebden Bridge station and he shambles away. He has given us a magical leap day pinched out of time. “He’s a genius, isn’t he?” I find myself close to tears, but I can’t think what the moment reminds me of for over a month. It was this, from Wordsworth’s ‘Prelude’, its final comma one of the greatest punctuation marks in English literature, though none can rival the ‘big bang’ colon in “And God said, Let there be light: and there was light.”

Near me hung Trinity’s loquacious clock,

Who never let the quarters, night or day

Slip by him unproclaimed, and told the hours

Twice over with a male and female voice.

Her pealing organ was my neighbour too;

And from my pillow, looking forth by light

Of moon or favouring stars, I could behold

The antechapel where the statue stood

Of Newton, with his prism and silent face.

The marble index of a mind forever

Voyaging through strange seas of thought, alone.

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Lou Crosby’s campaign posters makes visual the difference between a wind farm on peat, which will emit more carbon than it will save, and one on mineralised soil.

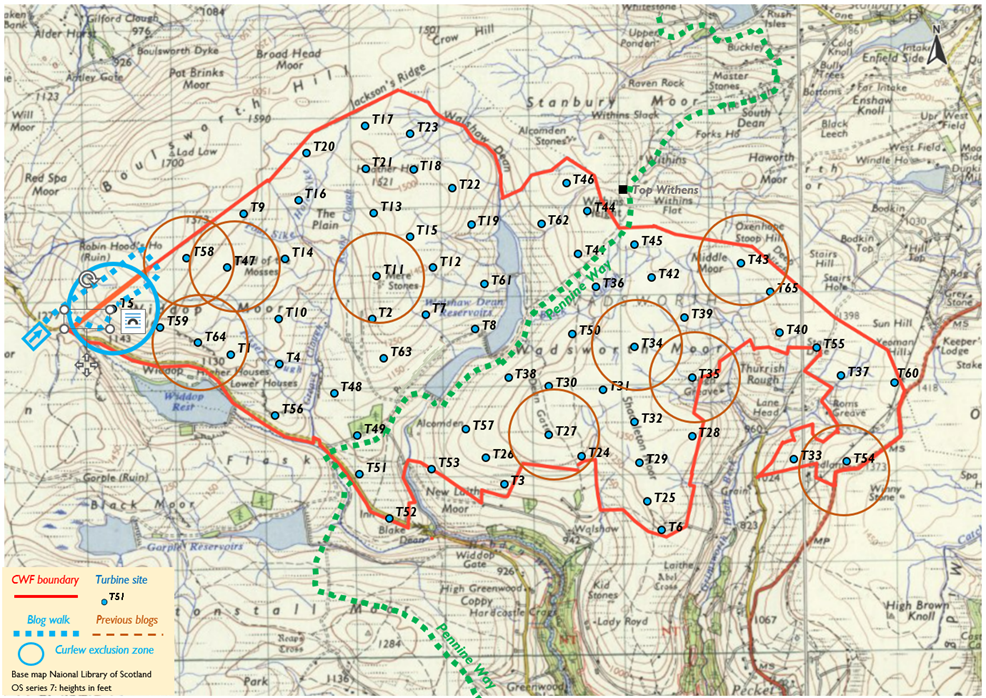

This is the 10th in a series of 65 guest blogs on each of the wind turbines which Richard Bannister plans to have erected on Walshaw Moor. Turbines 11, 27, 34, 35, 43, 47, 54, 58 and 64 have already been described. To see all the blogs – click here.

[registration_form]

I can imagine an Ordnance Survey chap asking a local what they call the features in the area he’s working on. “That one there is Pisser Clough .”

https://www.streetmap.co.uk/map.srf?x=394017&y=433630&z=120&sv=394017,433630&st=4&ar=y&mapp=map.srf&searchp=ids.srf&dn=520&ax=394017&ay=433630&lm=0

Yes, I’m looking forward to T1 Pisser Clough, and the sequel T4 Pig Hole Dike. Would you like to walk to either of them Tuwit? Drop me an email! Nick

Thank you for the very kind offer. I suppose I will now have to admit to one very strange hobby; I will scour OS maps for hours on end, looking for amusing, odd or insightful place and feature names. A hobby for when TV is interminably boring. This clough was already on my list.

Out pure blind interest, here’s another clough (in the Peak District NP, outside your immediate area of interest) that seemingly refers to no. 2’s.