John Page was born in the West Riding, a proud Yorkshireman and was taught to play cricket left-handed “’cos it flummoxes t’ bowler, and buggers up t’ field.” He went to university in London and Leeds, and enjoyed (most of the time) attempting to teach young people that there’s a big wide world beyond the Colne and Worth Valleys. He also taught future captains of industry and government at the United World College of SE Asia in Singapore for four years. Except Antarctica, John has travelled and climbed extensively on all the world’s continents, with friends and with Hil, his wife of 44 years. Still very active in his seventies, retirement from paid employment was the best career move that he ever made. This is John’s second blog here.

Motto: “How can there be peace in the world if we don’t understand each other; and how can we understand each other if we don’t know one another?”

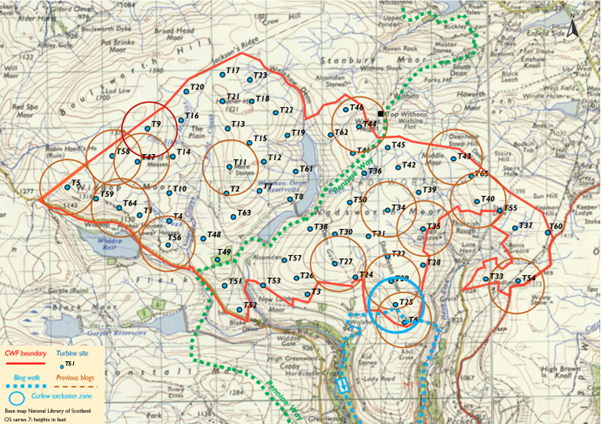

Turbine 25: Navvy Head SD 98328 31850 ///roadmap.replaces.shuttled

Towards the end of the eighteenth century, George Redman lived under Shackleton Knoll, at Lower Sunny Bank farm. South facing, it was an appropriate name. There were quite a few other members of the Redman family scattered up and down the Crimsworth valley. There were Inghams, Thomases and Greenwoods as well. Most families worked the dual economy, attempting to be self-sufficient in farming while weaving cloth in the sunny upstairs room of their homes. It wasn’t an easy life. Life expectancy at birth was about forty years, though those who survived infancy often lived beyond sixty. Still, lots happened during their shorter lifetimes.

It’s difficult to imagine their lives two centuries ago as one walks up the valley, but there’s plenty of clues to help us out. This present-day quiet, almost forgotten, walking idyll is the Crimsworth Dean valley; and up until it began to lose its population to the textile behemoths of the newly industrialising Calder Valley in the middle of the nineteenth century, over four hundred folk lived, worked, and loved here.

My walk slowly wanders up the valley, giving me time to think. Today there’s lots of talk about a crumbling welfare state, a cost-of-living crisis, and an acknowledgement that there are millions in our country who are suffering from fuel poverty. I’m not sure what George would have had to say about that; but it would have been interesting to have chatted to him about a Saudi-financed wind farm, looming over his valley. I suppose that George would say that he’d seen it all before … these new-fangled technological revolutions. He was just getting used to having to compete with the water-powered satanic mills in Hebden Bridge which were effectively sounding the death knell to his own home weaving industry. Indeed his many offspring would later need to work in the atrocious conditions found in the local factories to earn a living.

Part of George’s large extended family lived just a stone’s throw up the hill at Upper Sunny Bank (called Nook), located right on what would have been the busy thoroughfare of the Hebden Bridge to Haworth Road. The present-day main road past Cock Hill Swamp, which gives access to the wind farm, wasn’t built until the mid-nineteenth century, initially as a turnpike.

And all the houses, barns and field boundaries were built using local stone, most of it coming from the extensive quarries on the top of the nearby Shackleton Knoll. No need for cartloads of limestone from the Dales, as the current proposal for twenty-six miles of “floating” roads for the wind farm would require.

Robert was one of George’s sons. He lived in the family home, courted a girl from just up the valley called Isabel Ingham and married her in June 1817 in Halifax Parish Church. Obviously between the two families there must have been a bit of spare money squirrelled away because I’m sure that a wedding in “that fair town,” half a day’s walk away, wouldn’t have been a cheap do, especially as the mid-summer evenings were long.

I’m on my way to the site of Turbine 25 of the proposed Calderdale Wind Farm, walking along the valley bottom from the NT car park at Hardcastle Crags to Lumb Falls from where I’ll walk up to Sunny Bank and Nook, and then up Coppy Lane and onto Shackleton Knoll. The last building before the open moor is Coppy; just inside the intake wall. It was built around 1816 as a wedding present for Robert and Isobel, and later lived in by Luke, who was to be their only child. Isobel was already pregnant on her wedding day.

I’ve often wondered about the practicalities of family life all those years ago, from the luxury of my centrally heated home with its modern conveniences. My son was born in an NHS hospital in Halifax, my daughter in another well-equipped NHS maternity unit in Huddersfield. Isabel gave birth to little Luke Redman at Coppy Farm in a very cold January in 1818, and sadly she died in the process.

The winters in that decade were particularly harsh. Indeed during the years following the massive volcanic eruption of Gunung Tambora in Indonesia in 1815, the world experienced “several years without summers”. This had a devastating effect on the local Crimsworth economy; indeed it’s documented that representations were made by the tenant farmers of what was then Lord Savile’s estate for rent relief and other assistance as crops didn’t grow and animals died. Families had a terrible time.

In 1818 Robert was now without a wife, his new-born without a mother. As a young farmer the immediate prospects were grim and the family weaving business now had no future. What would I have done in those circumstances?

Robert did what any self-respecting person would do. He went in search of work, selling his labour wherever it was needed. So he and his mate, Jonathan Crabtree from Walshaw Wood Farm, walked over Widdop in search of work in the new cotton mills of Colne. Sadly though, along the way, tired and hungry, they were tempted to steal some silver spoons from Slitterforth Farm, near Trawden.

Just a few days later, James Wilson, the efficient constable of Heptonstall, arrested them. Robert and Jonathan were not habitual villains, just a couple of naive, desperate young men. Wilson and five other men then took them both to Lancaster Gaol, where they were judged to be “wicked” and duly sentenced to death, later commuted to transportation for life. They were sent south, incarcerated in a prison ship in Sheerness for almost a year and then transported separately to penal colonies in Australia.

Although I’m unsure what happened to Jonathan in Tasmania I know that Robert did survive, eventually becoming a free man after several years, marrying and obtaining his own farm down-under, before he died at the ripe old age of sixty-eight. Ironically he’s buried in the small town of Rylstone, New South Wales and Swinden Quarry, Rylstone, North Yorkshire is the possible source of the limestone for the proposed roads of the wind farm.

Robert outlived his son by almost 40 years. Luke died in squalid conditions in an overcrowded lodging house in York. He’d left the Crimsworth Valley in his mid teens to make his future in Huddersfield. But, married to an immigrant Irish woman, and later working for a candle maker in the middle of York, he succumbed to typhus, the Irish Fever, reputedly brought over during the mass famine migrations of the 1840s.

So, that’s a brief account of a slice of life up the Crimsworth valley. I’m sure that Sally Wainright could write a drama about it. Halifax-born Phyllis Bentley certainly did , although her book, the masterpiece Inheritance (1932), was based on family life in the Colne Valley.

I normally trot down to the National Trust car park from my home at Slack to start this round; but I’m carrying my camera (poor excuse), it might rain (there’s no such thing as bad weather, only poor clothing) and, to be honest, it’s far easier starting (and finishing) at the bottom of the valley; and where I can meet for a pot of tea (and cake) with friends in Hebden Bridge at the end. Equally it gives me the opportunity to chat to any folk I meet, spread the word about the evils of the wind farm scheme and attempt to make them a little bit more aware of what might be happening to the green and pleasant land up on the tops that they’ve travelled so many miles to walk through.

In many respects it’s an industrial archaeology walk, much of it is associated with water. There’s the pumping station and architecturally unique Victorian pipeline stone bridge just up from the NT car park. This pumps water from Widdop reservoir up to the tunnel that ingeniously takes the water beneath Midgely Moor, so that it then can flow by gravity through pipes into Halifax.

The long-overgrown mill ponds and goits which would have served the small fulling mill and dyeworks at Midgehole are fascinating; and the narrow, recently waymarked, path that follows them has been improved to enable less agile folk access into this archaeological wonderland. And there’s little runs of stone steps and causey stones, abandoned field barns and stone walled enclosed fields. The Crimsworth Dean still cascades over old weirs; and even though there’s still evidence of finely cut gritstone blocks channelling the river in places, it’s now retired and flows without hindrance through the sylvan valley. And today, after weeks of constant rain, all the vegetation is luxuriant and glistening green. It really is quite beautiful.

Some of the old farms have been renovated and rebuilt and Wheat Ings and Outwood are fine houses now. But there are long lost voices, no doubt, in the dereliction of Helliwell Wood, Baby House Hill and Shepherd’s Lodge old farms, as well as the old Redman fiefdom of Sunny Bank, Nook and Coppy! A community once buzzing with life.

People have already written in recent turbine blogs of the steep Sunny Bank road from Lumb Falls, immortalised by Ted Hughes. Unlike Ted’s “six young men” I’m from the lucky generation that never had to fight in a war. Again, I wonder how I’d have coped. I often come up to the “terrace” of the old Sunny Bank Farm on a pleasant day with a book to quietly read. Today you can see right across to the “new” church in Heptonstall, not built in George’s day; but he would have been able to witness the original monument on Stoodley Pike being built in 1814 from his terrace. Indeed the 270-degree sweep across and down the valley is quite special. Whichever of George’s forebears had Sunny Bank built, they were canny geographers.

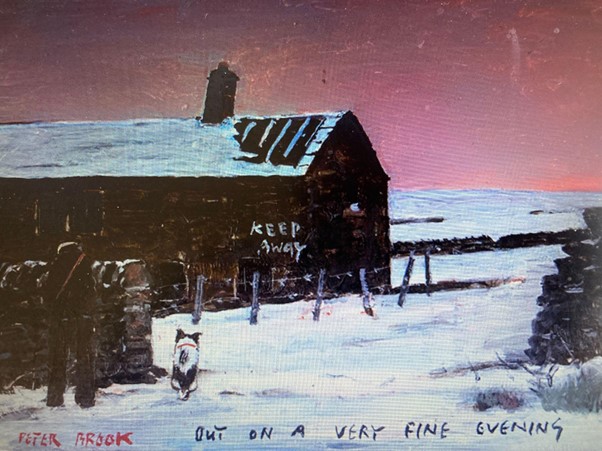

I walk steeply up to the Nook crossroads and then continue to Coppy Farm. It’s my favourite ruin in the Upper Calder. It was abandoned by the Greenwood Family at the start of the twentieth century, used as an occasional shepherd’s shelter until the 1950s and then left to decay. My late friend Peter Brook did a wonderful painting of it as part of his Calderdale collection, not long before he died. It appears at the end of the blog.

Coppy is a significant unofficial historical monument. The ghosts of Robert, Isabel, and Luke, and of the Thomas and Greenwood families who also subsequently lived there, would be within the turbine flicker of T6 right on the extreme edge of the enclosed land. I try to imagine the families working the land; occasionally going up the wide Coppy Lane and up on to the moor to cut peat turfs as fuel for the hearth.

From the intake wall gate, just before the moor, there’s now a well used path to the top of the knoll, tramped out over recent years by fell runners, following the route of The Hebden, a long distance fell race. Once on the top, I go back from the edge of the T6 site to Navvy Head. Who were the navvies? Where did they come from? How was the stone transported? Where did they sleep and what (and by whom) were they paid for their labour? Were they itinerant workers moving on from building the Rochdale Navigation Canal. Lots of questions, most left unanswered.

In the grey summer mizzle back at T25. I stride out twenty-eight yards. It is the diameter for the base for T25, three times the length of a typical house. I walk about 88 yards in a circle (C = 2πr) to approximate the circumference and then work out that the area (A = πr2) of the base would be 616 square yards. The depth of a turbine base is about six yards, four thousand cubic yards of concrete! And Google tells me that one fully laden lorry can carry up to ten cubic yards of concrete so that’s four hundred loads of concrete for just the base of T25. Multiply that by sixty-five for all the turbines, and that’s 26,000 lorry loads of concrete to be driven across the twenty odd miles of new “floating” roads that Nick tells us would require 45,000 lorry loads of Swinden quarried stone to construct. No wonder a spokesperson for the wind energy industry, on the BBC’s Today programme recently, kept emphasising that renewable energy was only carbon neutral at the point of production, once all the infrastructure was in place.

By this point my brain was hurting. The rain was thickening so I headed down, startling the somnolent sheep as I ran across the fields to Walshaw. I then shuffled down the long track through Hardcastle Crags and my car, thankful that I didn’t have to haul myself back up to home via the Hebden Hey Scout Hut. A pot of tea and a giant slice of cake in Hebden, instead of another uphill trek, seemed a more sensible option.

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Peter Brook (1927-2009) was born in the Pennine village of Scholes. He was elected in 1962 as Royal Society of British Artists. He taught at Sowerby Bridge Grammar School, building up a successful art department, taking pupils out to draw the surrounding country: ‘If you want a subject, look around you.’

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

This is the 17th in a series of 65 guest blogs on each of the wind turbines which Richard Bannister plans to have erected on Walshaw Moor. Turbines 5, 6, 9, 11, 27, 32, 34, 35, 40, 43, 44, 47, 54, 56, 58 and 64 have already been described. To see all the blogs – click here.

[registration_form]