Nick MacKinnon is a freelance teacher of Maths, English and Medieval History, and lives above Haworth, in the last inhabited house before Top Withens = Wuthering Heights. In 1992 he founded the successful Campaign to Save Radio 4 Long Wave while in plaster following a rock-climbing accident on Skye. His poem ‘The metric system’ won the 2013 Forward Prize. His topical verse and satire appears in the Spectator, and his puzzles and problems in the Sunday Times and American Mathematical Monthly. Email: [email protected]

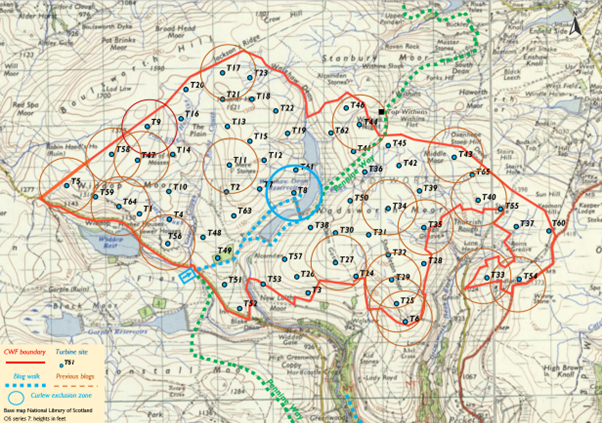

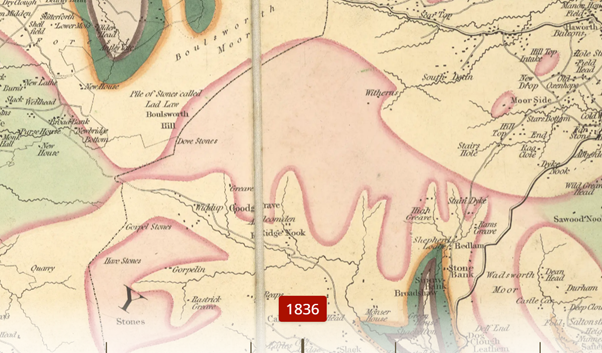

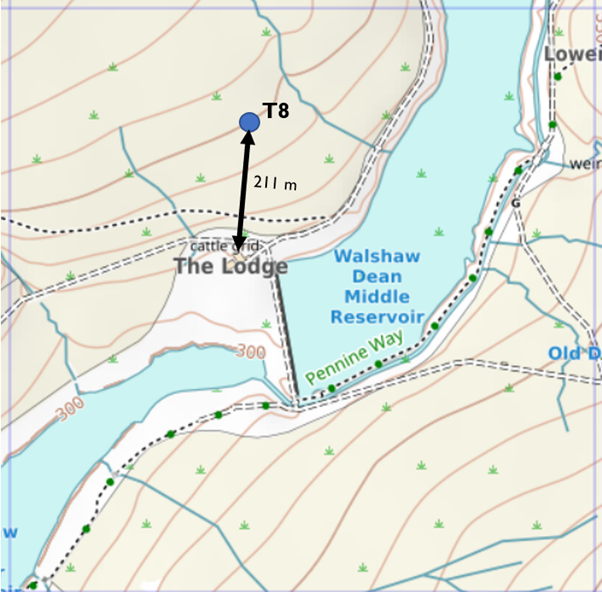

Turbine 8 Walshaw Dean SD 96408 33802///intersect.hologram.target

29 August 2024 Sheila Tilmouth and I are walking up the Pennine Way with poet Carola Luther, who has been a friend, collaborator and, on today’s evidence, sparring partner of Sheila’s for decades, since she moved to the South Pennines from South Africa in 1981. Carola’s brisk and easy demeanour is put aside in performance. “The hairs on my arms went up like a porcupine and my friend was in tears throughout” is what you can look forward to at a Luther poetry reading. Sheila has just spent the first night in her new house. “It was filthy. I sloshed a load of bleach everywhere and put up my camp bed. I think I’m going to like it. I have a room for my microscopes, a room for my soil, and a room for my freezers.” Those who have followed these blogs will have some idea of what is in those ominously plural freezers.

I have a flashback to the freezer scene in Shallow Grave. It is a hallmark of genius that Danny Boyle directed both that harrowing black comedy and the cosy but complex 2012 Olympic opening ceremony, at which Kenneth Branagh, dressed as Isambard Kingdom Brunel, high priest of the age of coal, spoke the loveliest words ever written in English, those of the dispossessed and enslaved monster Caliban in Shakespeare’s The Tempest. “Be not afeard. The isle is full of noises,/ Sounds and sweet airs that give delight and hurt not./ Sometimes a thousand twangling instruments/ Will hum about mine ears, and sometimes voices…”.

Carola has been on Sanday, where seventy-seven pilot whales died after stranding. “The locals buried them. They didn’t want any help. They took the burden to themselves and their community. They were told they all had to be disposed of on land, but they gave one whale back to the sea.”

We have been walking 10 minutes when we are overtaken by Apollo on a quadbike, the kind of apparition that is NFW: normal for Walshaw. He is God to hundreds of sheep and has three dogs to help him: an Australian kelpie, a New Zealand huntaway, and an old school collie. They travel on the quadbike too, forming a pyramidal composition like Leonardo’s Virgin and Child with St Anne.

This is the happiest man I have ever met. I daren’t attempt the loveliness of his Calderdale speech pattern. He went down to Herefordshire to get the kelpie and huntaway. They are born ready to look after sheep unsupervised, unlike collies who must be intensively trained as they “seem much nearer the wolf”. On receiving this feedback from his employer, the collie slinks off to do some rote-learned rounding up while the naturally-gifted Antipodeans bask in our adoration.

I won’t say any more. You’ll meet him if you walk this way. When the BBC puts Countryfile out of its misery they can start again with the Walshaw Apollo as presenter, and Graham Bancroft from the Widdop end to keep it grounded. I hope he finds a big house and fills it up with children.

“From fairest creatures we desire increase,/That thereby beauty’s rose might never die …”

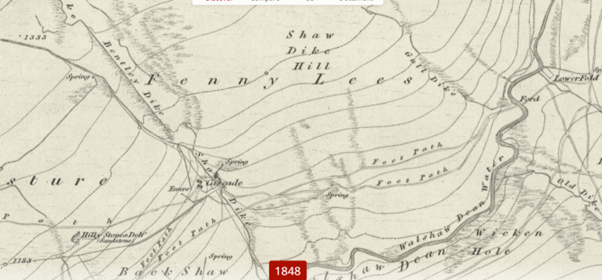

Carola has already spotted a house in which a pastoral deity can raise his demigods. It is unnamed on the OL21 of course, but marked Cascade on the 1848 six-inch map which pre-dates the reservoirs.

I put Lydia on the case, and she finds in the censuses a microcosm of the fate of Walshaw Moor.

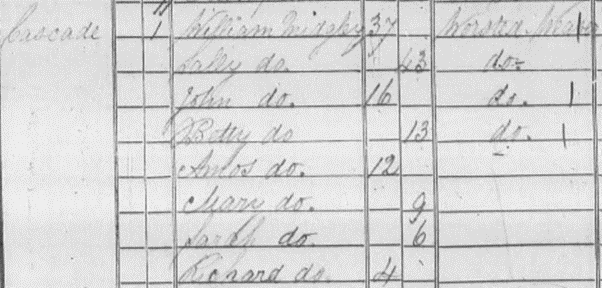

In 1841, Cascade was lived in by William Midgley (37), his wife Sally (43) and children John (16) and Betty (13) all worsted weavers, and younger children Amos (12), Mary (9), Sarah (6) and Richard (4).

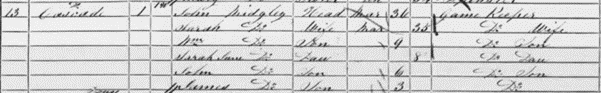

By 1860, John Midgley (36) is living at Cascade as a gamekeeper with a wife and four children. The mills have put the handlooms out of business, but John has caught the wave of the Victorian grouse shooting boom, itself driven by the railways and a new clientele of factory owners who want to network.

By 1871, Cascade is uninhabited and John Midgley (46) is living as a gamekeeper with his family at Clough Foot, where our walk started.

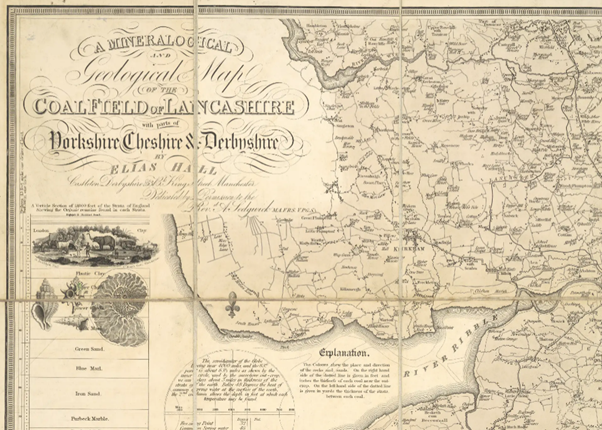

While we’re in the industrial revolution, readers who wonder about the strange shape of CWF might like this geological map of Lancashire from 1836 by Elias Hall. The map, made to expedite the exploitation of a fossil fuel that would power Enoch Tempest’s locomotives up to the Walshaw dams, put the Cascade Midgleys out of business, allow billions more people, including me, to live above subsistence, bring men and their guns from Leeds and London, and increase the CO2 in the atmosphere to levels last known in the Pliocene, looks utterly lovely.

There are many squashed frogs on the tarmac but Sheila contents herself with photographs. The one above shows a lovely Turing pattern on the skin, named after the codebreaker and computer pioneer whose masterpiece paper, published in August 1952 after his conviction and punishment by hormone treatment, founded the entire theory of the biological basis of animal patterns: zebra stripes, leopard spots and our poor frog’s contour map.

I spot a dead newt, and we gather round it. I fancy it is the palmate, Lissotriton helveticus, for it is less crocodilian than the smooth, and in its preferred acidic, heathery habitat. The developer’s nightmare, a great crested newt would be too good to be true. Muttley would say I had brought it here in a Tupperware box and trodden on it. In 2002, seemingly sane members of the management at school told me I had set fire to my own climbing wall, even though there lived among us someone who had torched Martin Bashir’s daughter’s tricycle, and about whom I had four days earlier written to the Deputy Chairman of the Bank of England, who had passed my letter to the boy’ father. I must seem the kind of anarchist who would set fire to my own property or assassinate a great crested newt for political gain.

Many thanks now to Nigel Griffiths who sent us with these photographs from what he thinks must be a CWF reptile or amphibian survey. The numbered carpet tiles were placed on the verge along the track to Walshaw Dean. When he went back on 23 September they had gone. He wonders why you would look for reptiles and amphibians so close to the road unless you didn’t want to find any.

Sheila is just getting focus on our newt when a pick-up stops and the driver says sarcastically, “You should line yourselves up like ninepins.” I get up to apologise.

It is the sorcerer Prospero from The Tempest, and our conversations during the next hour amply confirm his command of the elements of earth, water, air and especially fire. There is something in the deep Walshaw peat that generates these charismatic people. “How many goodly creatures are there here! How beauteous mankind is! O brave new world that has such people in it!”

“You walking the Pennine Way?” I take a deep breath and say, “No. We’re wind farm campaigners.” He offers a capable hand out of his window. “I’m the only freeholder on Walshaw. Four acres I’ve got. I bought them from Yorkshire Water with the ruin of Walshaw Dean. I’m not going to say anything about the wind farm either way because you don’t fall out with your neighbour. But if he gets planning permission and is no longer my neighbour, well then, you’ll hear a thing a two, because nobody in England will live nearer a two-hundred metre wind turbine than me.” It is true. T8 is 185m from the curtilage of Walshaw Dean, 211m from the house itself, and if it blows over in a northerly, 15m of blade will be in the Getty garden. The planning laws that govern such an imposition are described later.

He introduces himself. “I’m John Getty.” He may have caught my alarmed glance at his intact ear. “No relation.” When he bought Walshaw Dean its windows were boarded up and lead had been stripped from the roof. “The glass was an inch thick in places and full of bubbles. The window frames were solid oak, but Yorkshire Water had hammered in six-inch nails and bent them back, so the glass was broken.” John is the owner of PDS Engineering and has helped make several record-breaking vehicles. On his phone he shows us photographs of a grinning Richard Branson. PDS made many precision parts for the pressurised balloon capsule in which the Virgin magnate circumnavigated the earth. We are invited to consider momentarily a glamorous biker chick in ringlets and leather whom John says is Mrs Getty, before he swipes to Thrust SSC, the only car to exceed the speed of sound, whose hubs and stub axles were engineered by PDS.

He restored the framework of John Campbell’s nemesis Bluebird and made many of the precision components of the fastest steam-powered car Inspiration.

He won two bronze medals in the Isle of Man TT on a Suzuki 1100, but following a smash in the race he uses a powered wheelchair to get about. “You want to know how seriously they take SSSI? I was trying to mow a bit of lawn around my house. Two men come and tell me it’s SSSI and I’ve got to stop. Obviously, I’ve got the deeds, and a load of other documents and I was able to prove it had been garden.” He leaves us to draw the unspoken comparison with the treatment of 2352 hectares of SSSI by the proposed Calderdale Wind Farm. Walshaw Dean is remarkably grand. I ask John what happens in the annexe, which anywhere else would house a billiard table. “That’s what the waterworks committee of Halifax Corporation called ‘the centre of the known universe.’ That was their boardroom.”

John has a lot more time for this nineteenth-century predecessor of Yorkshire Water than he does for today’s “bloody vandals”. “You see I’ve got tarmac going to the house? When Yorkshire Water did the big work on the dam their vehicles had left huge potholes. It had come to the last day when the concrete was being delivered, so I got a flat shovel, like your grandma had for her stove, and a few chippings and drove out to the worst bit. I got in my wheelchair and was filling a pothole when the convoy of cement mixers arrived. I told them I was the only person with a legal right to use the track and now I was mending it, but I’d talk to the CEO, and they’d better hurry because their concrete would be going off. I shook a few chippings off my shovel. The foreman came back and said he couldn’t get a mobile signal. I sympathised and suggested he used his radio link. I shook a few more chippings off my shovel. Eventually they got the Chief on the radio, and he promised me they would tarmac my track. And as you see, they did!”

He remembers the ‘once in a hundred year‘ flood. “It was a foot deep over this road, pouring down the hill and into the rezzy, which was full of what Yorkshire Water called ‘stock’, so it went straight into the spillway towards Hebden Bridge, and you know what happened then.”

As though summoned by Prospero’s words, it starts to rain, and we make our apologies and say we were heading for the turbine site above his house. John Getty is a link to the golden age of fossil fuels that began with James Watt and ended on 25 June 2000 when the Daily Telegraph printed Gyles Brandreth’s interview with Sheikh Yamani. “Oil will be left in the ground. The Stone Age came to an end not because we ran out of stones, and the Oil Age will come to an end not because we have run out of oil.” Some say the apex was slightly later, on 2 May 2007, when Jeremy Clarkson and James May drove a car to the magnetic north pole. But a redeemed Clarkson, who would welcome a cameo from the Walshaw Apollo on the beloved Clarkson’s Farm would agree that “our revels now are ended” and “melted into air, into thin air”.

Clarkson’s Farm is unafraid of examining the complexities of our relationship with nature and climate change. In the Guardian it has gone from “1* total contempt for farming … a grim harvest … wearisome meretricious rubbish” to “4* ever-compelling … wildly popular … gives airtime to discussion of agrarian monocultures … well-made television and perfectly balanced … one of the best things that has happened to farming.” One day, the birds that breed on Walshaw Moor will need Ed Miliband to demonstrate the same command of nuance and complexity as Jeremy Clarkson.

We look over the dam in the hope of seeing the megalithic stone circle. We’ve given up when John comes out on his powered wheelchair, not quite an all-terrain vehicle, but speedy and manoeuvrable out here in the wild. He pulls himself up on the wall and points out a few bigger stones. Suddenly Carola can see it and then by morphic resonance we all can. Now we have the diameter we can also see what John thinks is an outer ring. He points to a huge stone on the edge. “That was once part of the circle, but it was moved to make a winch anchor when Yorkshire Water got a tractor stuck in the rezzy. The circle was much clearer when we moved here forty years ago, like Stonehenge without the lintels.” He points us towards the gate into CWF and reminds us of our right to roam all over Mr Bannister’s property.

John Getty may be discreet for now about his neighbour of earth and air, but the “bloody vandals” at his water gate get no mercy from the Prospero of Walshaw Dean, who is in no mood to say, “I’ll break my staff, Bury it certain fathoms in the earth, And deeper than did ever plummet sound I’ll drown my book.”

“Last thing. See that wall on the dam edge. Those blocks look like stone, but they’re concrete. When somebody complained about how they looked, the builders brought a bowser of slurry and sprayed the wall so that moss might grow.” As Sheila’s photo shows, sometimes when Yorkshire Water pours shit into our supply, it works.

“The blocks are held together with cement. When the inspector came, he asked the lads where the water had come for the mix. ‘Out of reservoir, of course.’ He tells them to start again. ‘That water’s too acid to make cement with. Take it down and use distilled.’” Hope flares momentarily that this will stymie CWF, but the concrete batching plant will be at Cock Hill Swamp and plumbed into the mains. The turbine foundations will be protected from the acid peat by a plastic membrane. Decades after the turbines have gone, these membranes will fail, and iron sulphate, the active ingredient in moss killer, will leach from the steel rebar and destroy what is left of the sphagnum.

The Wind Turbines (Minimum Distances from Residential Buildings) Bill began in the House of Lords and was proposed by Lord Reay. It had made no further progress when parliament was prorogued at the end of the 2010-12 session. Section 4(d) stated that the minimum distance for a turbine of height greater than 150m was to be 3km. Under this law, John Getty’s house would exclude almost every turbine in CWF. Lord Reay’s ancestral lands were once in Sutherland, where the Residential Buildings are, if inland, much grander even than Walshaw Dean and more remote and it may have been these castles and fortified houses that Lord Reay was seeking to protect. Residential Buildings had their roofs burned during the Clearances, and the crofters fled to the seashore where they subsisted on limpets until they could be shipped off to Canada. Such descendants as remain inhabit the coastal strip of an empty land. The Reay Forest, now owned by the Duke of Westminster, could host a huge wind farm under the constraints of his Lordship’s Bill, but not Walshaw Moor.

There is in fact no legal minimum distance between a wind farm and a residence, though ‘tip height plus 10%’ is quoted as desirable. With a whole moor to put it on and one house to avoid, it is typical Muttley carelessness to site T8 as close as it is to John Getty’s house. I cannot believe Mr Bannister, a gentleman, will allow T8 to stand now he knows what this minion has done to a neighbour.

A gamekeeper, successor to John Midgley, and probably living in his house at Clough Foot, drives past with two shotgun cases on his quadbike. We meet his thousand-yard stare and exchange micro-nods. A rough track leads into Bannister Country past the plastic beehives, which are lashed to a palette with orange straps. They recall the improvised Dawson City which housed the navvies who built the reservoirs, commuting in by train over Blake Dean on Enoch Tempest’s trestle bridge.

Now we are lined up with the dam we go straight up the hill until we are 185ms from John Getty’s garden and we are on the site of T8. In front of us are the elemental works of man, the burned heather strips, the dam’s masonry, the sullen reservoir, and the prospect of harnessed air. What would the waterworks committee of Halifax Corporation in their board room at ‘the centre of the known universe’ in the golden age of fossil fuels have made of Calderdale Wind Farm?

If the question were simple, we wouldn’t be here. Here is one nuanced answer. The Corporation had put the Walshaw work out to tender and received five strike prices.

Enoch Tempest, Manchester £169,501

S Pearson & Son Ltd, London £201,500

Geo Macking & Sons, Edinburgh £253,179

Naylor Bros, Huddersfield £257,152

Monte & Newell, Bootle £353,567

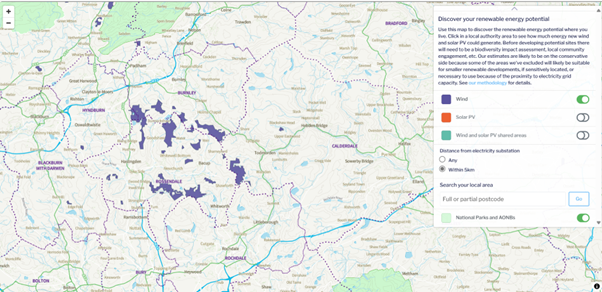

The Corporation chose Tempest. If assembled again in John Getty’s annexe, the committee would say that wind power was a wonderful thing, but wasn’t this rather an unnecessarily expensive project? Could the same energy not be harnessed more cheaply, and thus more extensively, upwind, and with less damage to God’s creation? Friends of the Earth think so. They want the same westerlies harvested to the west, where there is no SPA, the access is inexpensive, and the substations are close. The needs of we billpayers and our climate are harmonized if we build the wind farms in the right places, thousands of them quickly, rather than bowing to the whim of a grouse moor owner whose hens have lost their mojo, or as Deep Stoat puts it, “The new manager has lost the dressing room!”

We separate for a bit and another wonderful day on Walshaw settles into my soul. It is still, and heather musk hugs the ground. I can hear bees who have commuted here from their polypropylene shanty town.

Sheila, as so often, finds beauty in this burned place, Carola less so: “It’s fucked.” There are indeed decades of gentle work to set Walshaw Moor straight, so it can once again transmute our fire back into earth, but it is waiting.

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

This is the 20th in a series of 65 guest blogs on each of the wind turbines which Richard Bannister plans to have erected on Walshaw Moor. Turbines 5, 6, 9, 11, 17, 25, 27, 32, 33, 34, 35, 40, 43, 44, 47, 54, 56, 58 and 64 have already been described. To see all the blogs – click here.

[registration_form]

I love the way Nick dances the line between laugh out loud and deadly serious. Not perhaps the easiest of images.

The Turbines raise so many issues: the violation of the literary and natural landscape; the degredation and worse of the peat bogs; whether or not they make economic or scientific sense, that it is easy to lose sight of the fact that in opposing this proposed act of desecration you must also WIN all these arguments. Simply protesting them is classic nimbyism.

To do so requires inormation presented with the rigour, clarity and inclusive good humour Nick’s blogs demonstrate. It is also essential to avoid at all costs privileging any one argument over the others or worst of all advancing them as competing causes.

I mention this insane proposal to everyone I meet. The usual reaction is that people whilst sympathetic (“How many? Where?”) are very reluctant to oppose anything that mitigates the challenges of Climate Change which is an almost religious force in the world. Also variations of Ian and Myra’s (Blog 14 Turbine 44 – a classic) “They have to build them somewhere…” but when you describe all the issues at least one and normally many of them will rapidly pursuade them to at least look into it and thats all it takes.