John Page was born in the West Riding, a proud Yorkshireman and was taught to play cricket left-handed “’cos it flummoxes t’ bowler, and buggers up t’ field.” He went to university in London and Leeds, and enjoyed (most of the time) attempting to teach young people that there’s a big wide world beyond the Colne and Worth Valleys. He also taught future captains of industry and government at the United World College of SE Asia in Singapore for four years. Except Antarctica, John has travelled and climbed extensively on all the world’s continents, with friends and with Hil, his wife of 44 years. Still very active in his seventies, retirement from paid employment was the best career move that he ever made.

Turbine 16: The Sod SD 94469 35253 ///canal.river.ripe

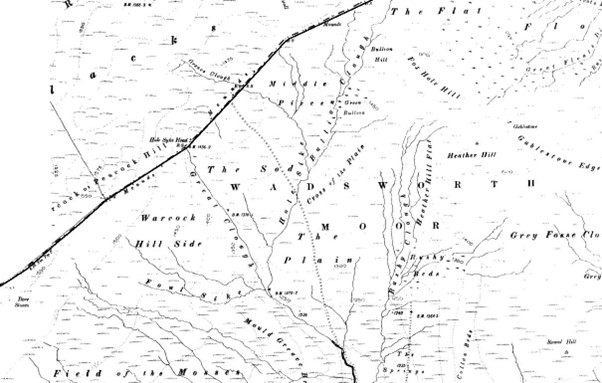

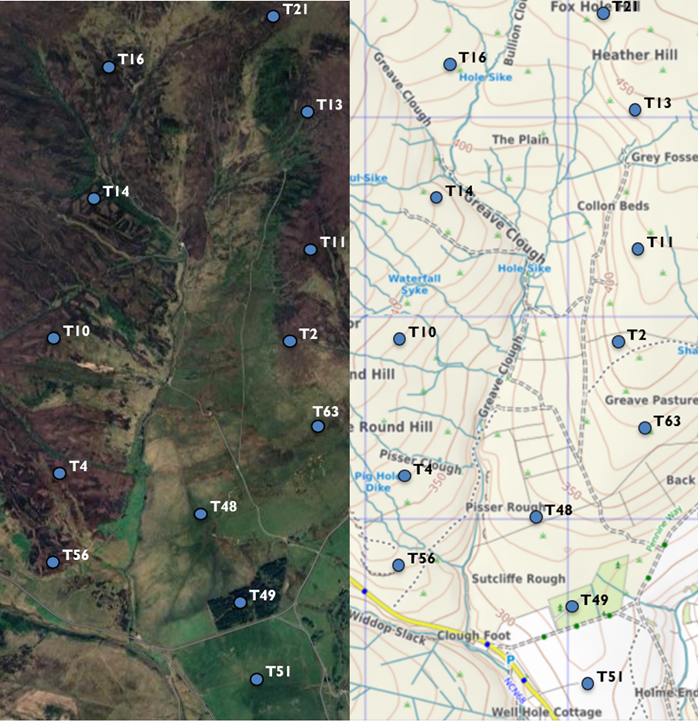

20 November 2024 T16 is to be located on The Sod! On the 1894-96 OS map The Sod was accessed by a footpath originating just west of the Pack Horse pub. Mr Bannister can now get most of the way on the track system shown below. How will the construction vehicles and turbine blade delivery systems get there?

It started to snow at Slack Top, the day after I arrived home. A Calder Valley winter wonderland and a shock to my system. I‘d just spent a couple of weeks in my shorts, wearing just a T-shirt as I trudged through the Andalusian hills. This was a joyous 250 km linear walk, a Thanksgiving after my NHS surgeon had told me that I was all clear of cancer.

I had long days walking alone through interesting landscapes; friends and family asked if I’d been affected by the Spanish floods, particularly in Valencia. Yet in my pedestrian bubble the sun shone brightly every day and no rain fell; and even while Malaga was experiencing its worst flooding for 25 years, I was in a dry train travelling from Ronda to La Linea de la Concepcion on the border of Spain and Gibraltar.

The devastating floods in Spain are yet more evidence that the world’s climate is changing. As I walked through an agrarian environment the effects of climate change were all too evident. The summers are now much hotter; the rain now falls in ever more torrential storms and the changing climate only exacerbates and accelerates the exodus of young folk from the land, because of the economic unsustainability of upland farming practices. The famous white villages now have a disproportionate number of old folk in them. But, just as with the decline of the traditional textile industry in our own Calder Valley, offcumdens (mainly from Northern Europe) have come to the partial rescue. Now cheap properties are bought by incomers, done up and, in a lot of cases, villages and small towns have been revitalised. What is sometimes called gentrifying is like Hebden Bridge with more sunshine.

And my walk was a microcosm of a fast-changing world. Just before my walk in Spain I’d driven my daughter’s van out to the French alps to help her settle into her new apartment in an old hotel. The area was once famous for its sanatoriums to prolong the lives of thousands of ill people. When TB was tamed by antibiotics, the art-deco sanatoria and hotels in the mountains were left to decline, until the outsiders have come in and are rehabilitating the area: the hippies of Hebden; the expats of Andalusia and my daughter in Plateau d’Assy. In 2002 the Bannisters purchased the declining shooting estate of Walshaw Moor from Lord Savile. As with each reinvention of an area, by definition, not only will there be socio-economic changes but there will be changes to the physical environment as well.

In the Alps I visited some of my old climbing haunts. The world famous Mer de Glace has now shrunk by almost one hundred metres in depth during that time. In the sixty years since my first visit, the whole area has changed dramatically. Whereas I would get out of my old minivan and walk just a few metres to the Bossons Glacier and practice using my ice axe and crampons, before testing myself on more serious mountains, the snout of the glacier has now receded almost a kilometre from the road. Traditional transhumance agriculture no longer exists, alpine pastures are “rewilding” and alpine chalets, as with traditional Pennine farmhouses, are now the second homes of offcumdens.

My recent Easyjets from Geneva to Malaga cost £28; from Malaga to Manchester just £46. There is no disincentive for me not to fly.

And so it’s within this context of changing landscapes that I pondered while I walked to the proposed site of T16 on a bright day in mid November from beyond The Pack Horse on Widdop. The pub has been there since 1610. The name tells it all. But now, our drinking habits have changed; our social needs have changed and, wonderful as the old pub is, it is having a tough time. Is it living on borrowed time?

The old Savile estate has seen vast changes over the previous centuries. Farmed by tenant farmers in the dual economy initially; then, as home weaving gave way to the mills, pastoral farming became the mainstay of the upland areas. But in the late 19th and early 20th centuries many farming families on the now Walshaw estate were removed to make way for Halifax Corporation’s new reservoirs and catchments. And much of the land has thereafter been intermittently used as grouse moor.

I left the Widdop Road at the Notch, on an indistinct snowy groove in the ground. Although it’s shown on the OS map as a permissive path, and would once have been maintained by the Halifax Corporation, it’s now ill-defined and, in soft fresh snow, was quite boggy. After only a hundred metres or so, it passes the site of proposed T 56, just before Pig Hole Dike. There was not a breath of wind.

Eventually, the path joins one of Mr Bannister’s roads, by a control dam. We know that it’s Bannister track, and that it was constructed in 2002, just as he acquired the estate, because like Ozymandias he’s had a stone marker placed there to proclaim his works.

Anyway, it’s a good track, surfaced with imported aggregate, built along the line of a path that’s not shown on the 1854/6 OS map but does appear on the 1894/6 one. And, as the sun shone brightly, the track was a delight to walk on, at least to its terminus, just below the very boggy link to the ten new shooting butts. I trudged on, imagining Mr RB’s nouveau riche clients, in their Barbour coats and with flasks of coffee and whisky, waiting for the birds to be beaten in their direction. Butt 10 is the last of the line, on the 420 metre contour, with the proposed T16 turbine some four hundred metres cross country to the north-east. The butts are just above the infant Greave Clough and the turbine would be erected just a hundred metres or so south-west of the curving Hole Sike. But the quarter of a square kilometre or so of land that T16 would be in is wonderfully called The Sod, and is surrounded by Middle Piece, Green Bullion, The Plain and Warcock Hill: evocative names.

I stand where the turbine would be erected. The site is acknowledged by a small white post in the ground. Although I’d measured over 240 cm depth of peat on my previous outing to T31, I reckon that the depth here could well be double that, more than five metres. Calderdale Wind Farm Ltd’s own peat survey map shows this location to have the deepest peat on their proposed industrial estate, between 4.5 and 5.5 metres. So, again the ramifications for this site are severe. And, at 25 metre diameter for the turbine’s base alone, it would straddle two tributary groughs, disrupting the natural ability of the peat to absorb rainwater, and thereby increase the amount of surface run-off, particularly in the now more frequent intense storms; with the subsequent ill-effects downstream in the lower Calder Valley. Its location is sinister: ///canal.river.ripe. Millions of pounds of our taxpayers’ money has already financed the Environment Agency’s flood mitigation projects, but hard engineering is not the sole answer to controlling river flow. Thoughtful use of the catchment area is, though. It’s only common sense that adding more impermeable surfaces to our moorland, whilst at the same time destroying water absorption peatlands, is not a sensible idea.

And the other imponderables. How do you get a 200-metre tall wind turbine to this point? Located as it is, in the north-west corner of the proposed estate, will it, and the adjacent turbines be serviced by a new network of floating roads, built using the 70,000 lorry loads of Dales limestone that would be required, that would come in from Cock Hill, some five miles away to the east? Or would all the required infrastructure have to come in from Clough Foot, with mammoth vehicles negotiating the fragile Lee Wood Road and the bends of Blake Dean, or creeping past the drop into Rapes Hole at the western end? The logistics of access alone should render this area unsuitable for the short life span of this ignoble speculative venture. And that’s even before all the other well rehearsed arguments are used. I’ve written this many times before but, on a day like this, with excellent visibility and long range sight lines, the financial backers of this ecologically unsound scheme ought to do a proper site visit. I have spare pairs of wellies! It’s beautiful; but it’s an impractical location for the potential money making mega-industrial estate that CWF are proposing. I am not an accountant, but I would have thought that, unless the electricity produced is sold at a high tariff, the cost/benefit analysis on a spreadsheet would not make for pleasant reading for potential investors.

And with that thought I began to retrace my steps, but only as far as the “new” track (another RB 2002 addition to the landscape) that leads one past the remains of High Good Greave. What an amazing spot in this hidden “Shangri La.” Its extensive field pattern is still evident; dry stone walls, old stone gate posts.

On good tracks, and with wet feet beginning to dry, it’s a slow half hour potter back to my car. No need to rush, though. I’ve already explored the seven derelict old farms that I pass on the way. Echoes of a different time. Families were forced to move out because the land was deemed essential and vital for a societal need; no problem though that it enhanced the coffers of Lord Savile through the sale of another part of his estate to Halifax Corporation.

And Walshaw Moor? Is its location essential and vital for a societal need? An industrial estate to be built on irreplaceable peatlands, destroying a unique ecosystem to enhance the coffers of yet another of Lord Savile’s successors. And the glaciers continue to recede in The Alps and the droughts in Africa are longer and the rain in Spain is no longer mainly on the plain, but comes in the form of more intense storms on the coast. And Hebden Bridge’s “once in 100 years” floods are occurring every few years. The climate is changing before my very own eyes.

But building this monstrous wind farm on this special moorland will not solve the problem. Perhaps, collectively, if we tweak our lifestyles a bit, don’t engage in so much warfare, eat a little less meat … and on it goes. There are easy solutions to the world’s challenges; but difficult, if not impossible, to implement and enforce. Back to my diesel car and a five-mile drive home; but after a delightful few hours in the bitterly cold sunshine there’s a big bowl of vegetable stew waiting for me.

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

This is the 25th in a series of 65 guest blogs on each of the wind turbines which Richard Bannister plans to have erected on Walshaw Moor. Turbines 5, 6, 8, 9, 11, 17, 21, 25, 27, 32, 33, 34, 35, 40, 43, 44, 47, 54, 56, 58, 62, 64 and 65 have already been described. To see all the blogs – click here.

[registration_form]