Nick MacKinnon is a freelance teacher of Maths, English and Medieval History, and lives above Haworth, in the last inhabited house before Top Withens = Wuthering Heights. In 1992 he founded the successful Campaign to Save Radio 4 Long Wave while in plaster following a rock-climbing accident on Skye. His poem ‘The metric system’ won the 2013 Forward Prize. His topical verse and satire appears in the Spectator, and his puzzles and problems in the Sunday Times and American Mathematical Monthly. Email: nipmackinnon@gmail.com

Turbine 57 Lower Stones SD 96270 32701///discount.deflated.bowls

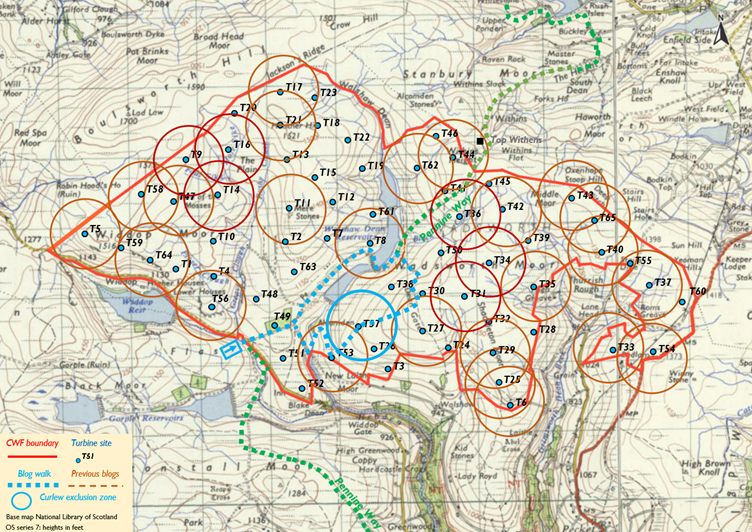

21 February 2025 Houses near Walshaw Moor have been sent forms asking for permission to install microphones to determine the background noise, so we are expecting a new Scoping Report for the application to the Planning Inspectorate soon. We granted permission provided the developer answered some questions about where the aggregate is coming from and why the peat survey is so incomplete west of Greave Clough. No reply. This new scoping report will replace the 2023 version for Calderdale Council that we have been steadily shredding in this series.

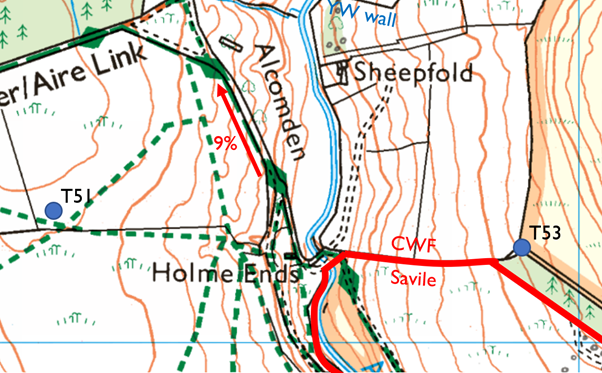

This blog will compare the engineering difficulties of Walshaw Moor with existing UK wind farms. Its initial focus will be on how to get the wind farm track down off the plateau to Alcomden Water, where there are presently two bridges, one Grade II listed, and one made of steel in the form of a cattle grid. CWF will add a third, strong enough to allow the 200-tonne crane to cross, and Alcomden Water will then be like the Firth of Forth.

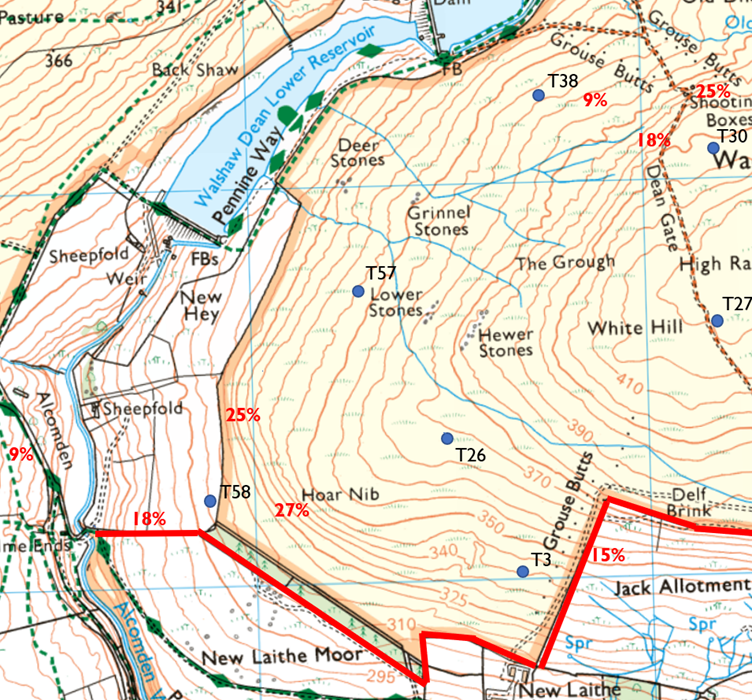

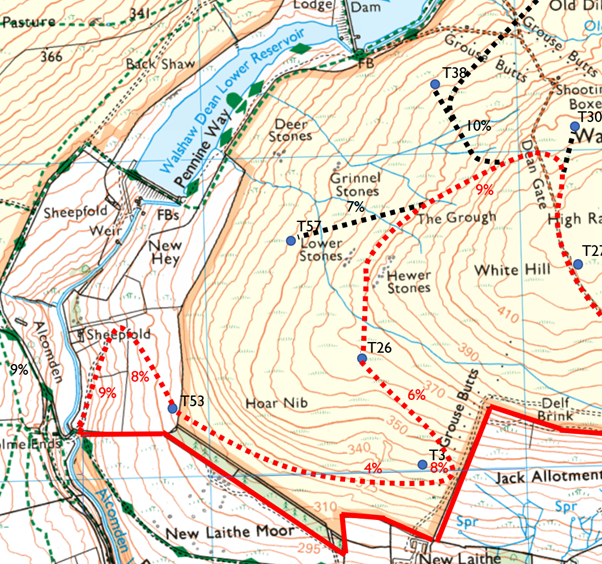

There are two different gradient challenges in getting down the face of Hoar Nib. One is the strip of close-packed contours on the moor edge, and the other is the steep valley side of Alcomden Water. The first is steeper, but the second is more difficult, because there is little room for manoeuvre.

I have heard it said that “It is impossible to get turbine blades down to the bridge.” They can be got down but it is an unprecedented engineering challenge inside a British wind farm. Access to a wind farm is sometimes steep and often finessed by using the tarmac of a strong public road. Inside wind farms the roads are made of crushed rock, and 9% is a maximum gradient on the spine road, though there may be short sections of up to 12% on spurs to individual turbines. Where this happens, the track goes straight down at right angles to the contours and special measures are described in the risk assessment.

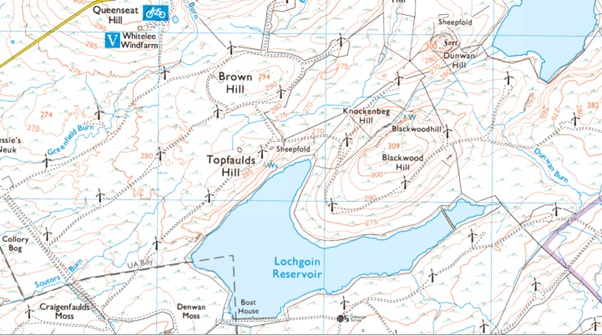

The photograph below shows the way an existing track network negotiates the steep valley side on the far side of Alcomden Water. This track has a gradient of 9%, so this is the maximum gradient expected of a crushed rock spine track. The line of this tarmac will have to be followed by the CWF track, but the width will be doubled.

This tarmac track could be built on a long traverse because there is very little peat. The grass is growing on ‘competent ground’ which is boulder clay spread by the last glacier on Lower Kinderscout Grit. If the ground were metre-deep peat, this traverse would not work because of the steep unstable peat above and below the track. The correct method in that case would be to cut a trench directly up, perpendicular to the contours, and fill it with aggregate. That wouldn’t work here because the direct route is an 18% gradient. Peat deeper than one metre and steeper than 9% is strongly avoided by wind farm spine roads.

We see that a track can be built to a wind farm spine gradient of 9% up from the bridge to the other half of the wind farm. Something similar would deal with the river valley below Hoar Nib, but the two sides of Alcomden Water are not symmetrical and there is a problem.

New readers may be wondering why the wind farm does not use the tarmac network and public road to Clough Foot as the centre of activities. The answer is that the single track Widdop road is not suitable for bulk delivery of aggregate, massive pylon sections nor 60 metre turbine blades. The access to CWF is from the A6033 Oxenhope to Hebden Bridge road “at the elephant”. Half the wind farm must come down Hoar Nib and then back up the other side, where the ascent is much easier, and first the hairpins must be built, using aggregate hauled from the elephant and delivered from somehere in the Dales. Scottish and Welsh wind farms don’t have this problem: they are built of onsite rock.

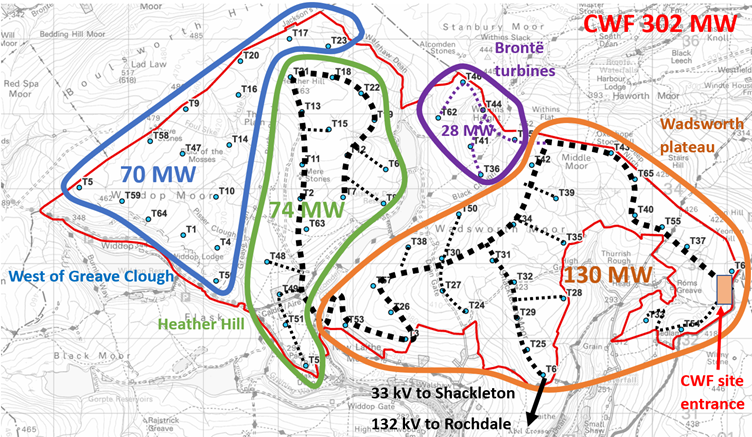

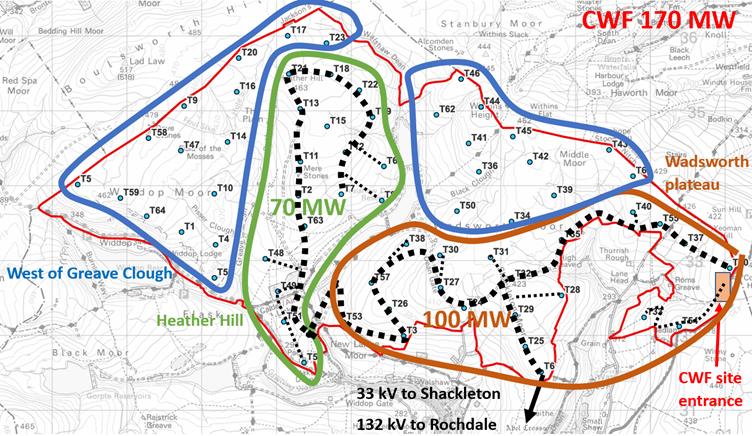

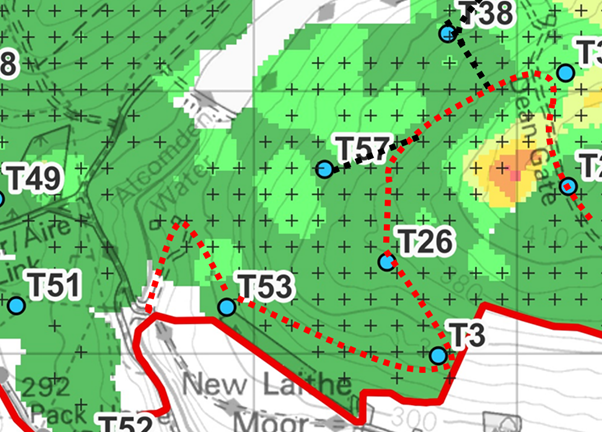

The message of those two maps is that there is a unit of terrain on Wadsworth plateau, outlined in brown, that might host a 100 MW wind farm if it wasn’t so protected, remote and inaccessible. There is a second unit of terrain on Heather Hill outlined in green, where the same could be said at 70 MW and where deep peat is more avoidable, but which is inaccessible without the 100 MW Wadsworth plateau. No other wind farm in the UK attempts to treat two such divided units as a single wind farm. Viking Shetland is an archipelago of smaller wind farms with multiple access from the public roads, two internal substations and a shared HVDC cable to the mainland. The reason the developers have to make the planners see CWF as one wind farm is that the access is stuck at the east end and the 132 kV connection to Rochdale is much too expensive to be carried by a 100 MW wind farm. In fact, Christopher Wilson has said that “CWF is not economic below 200 MW” even though he has promoted a 170 MW wind farm on his own website. This 170 MW CWF fragments the South Pennine SPA/SAC in a way that creates a precedent for further fragmentation. As such it destroys the integrity of the area-based conservation required by the Kunming-Montreal Protocol.

There can be an over-emphasis on peat in discussions of the protections to Walshaw Moor. The site is a Special Area of Conservation (SAC) because of irreplaceable habitat, now understood as a vital carbon sink, and a Special Protection Area (SPA) because of the red-listed birds. Curlews, lapwings, skylarks and meadow pipits breed in profusion on the grazing and tussocks, not only on the moss and heather of the deep peat.

The map above shows the problem on the east side. On the west the tarmac track exits the stream valley onto gentle slopes which form the extensive grazing of Greave Pasture. On the east the existing, soaking, rutted track is on about the right line, but the ground is hemmed in by the reservoirs (owned by Yorkshire Water) and Hoar Nib. To reach T53 needs a serious hairpin above the sheepfold. Although this field has little peat in it, it is very much wetter than the west side because it receives all the runoff from steep Hoar Nib.

I can only work with the layout provided by the developer. There is a simpler ascent of Hoar Nib from the bridge, but it leaves out T53 and the other sites forming the slalom on the steep face. The map below shows a possible spine road in red dashes with spurs in black linking the given layout. The traverses and hairpins are only possible because the peat is thin over Hoar Nib and on the valley sides. Readers will note a strong contrast with the slopes west of Greave Clough, where the peat is very deep, and these traverses will not work. They might get some turbines up on Walshaw Moor, and maybe even 170 MW if the government can stand the international heat, a free-for-all on every SAC and SPA in the country and still look Sir David Attenborough in the eye but turbines west of Greave Clough are another matter. I try in these blogs to make rational assessments, count the money, weigh the aggregate, identify the bed rock, read the annual aggregate assessments, measure the gradients, probe the peat, understand the treaties, and assess the oppo as misguided opportunists who are trying it on, as one does oneself sometimes, but you can’t work rationally in the face of Dalek-hearted ecocide.

Today’s walk is my first look at this steep drop. I made an earlier attempt with the dog, straight up from the lowest dam, but the estate wall is impassable for an Airedale. Today. I come the way of the turbine blades from T30, by first walking up the steep estate track from the second dam. This crosses the edge at about 20% past the shooting box and is of no use to CWF. As so often on Walshaw Moor, the tracks and established paths are not where the lorries can go. This track has a “blue granite” (the estate’s term) running surface over a disintegrating sub-base of onsite rubble. I have been told that rewetting of the moor by grip blocking is leading to much increased erosion of the tracks. This must be because the tracks act as replacement drainage now that some of the grips have been dammed under the agreement with Natural England.

At the top, I take a direct bearing for T57, which in practice means walking towards Sutcliffe Plantation. The rewetting may be working here because this is the mossiest ground I have been on for a while and the heather is thin, not at all like the thick growth on Middle Moor in the previous blog. There is no need to deviate at all until I reach Lower Stones. All this route is well within my nervous cross-country skiing gradient and a laden turbine delivery can come down this way.

From T57, I head straight to T58 to see what the last few contours are like if the Hoar Nib edge is taken directly; it’s too steep. A long traverse from T3 across this face is needed to get down, with the hairpin position implied by the published layout.

I step neatly over the wire into the grazing and start the hairpin in the steep field. The ground is so wet and steep I can’t go straight down. As in the photo below, a lot of excavation will be needed to make the hairpin, whose apex will be near the trees and must lie flat. At completion, this steep wet field will be full of expensive engineering: a hairpin with a maximum width of 20 metres protected by a deep drain to divert the runoff from Hoar Nib. This is a huge job, but the position of T52 at the top of the field implies it. A long rising traverse above the reservoir to the plateau would look less strange but would bypass the Hoar Nib turbines which would now be on spines that replicate most of the hairpin descent route anyway. If this was my wind farm and I was responsible for the safety of my work force, this soaking wet slalom would be built of concrete.

So, the descent of Hoar Nib to the new bridge is possible, but expensive and destructive. There is no knockout engineering argument against CWF. Instead, a steady accumulation of difficulties, none in themselves impossible, add up to an expensive project which will destroy its site. No other windfarm in the UK has an internal descent like Hoar Nib, but it is required in the 302 MW and 170 MW versions announced by Christopher Wilson.

No other wind farm in the world surrounds and destroys the inspiration of two of the authors in the top ten of the Guardian’s list of the greatest novels of all time.

1. To Kill a Mocking Bird 2. 1984 3. Lord of the Rings 4. The Great Gatsby 5. Anna Karenina 6. Jane Eyre (Charlotte Brontë) 7. Huckleberry Finn 8. Emma 9. Dorian Grey 10. Wuthering Heights (Emily Brontë). The next four are Brave New World, Frankenstein, Alice in Wonderland and Lord of the Flies. When we talk about British ‘soft power’, this list is central, and the British authors on it have also generated hard power billions for our economy. To get past the Brontë sisters, dead in their thirties, F. Scott Fitzgerald had to write The Great Gatsby, in which there is not a single word out of place. It’s a top one hundred: the Nobel Prize winners peak at William Golding.

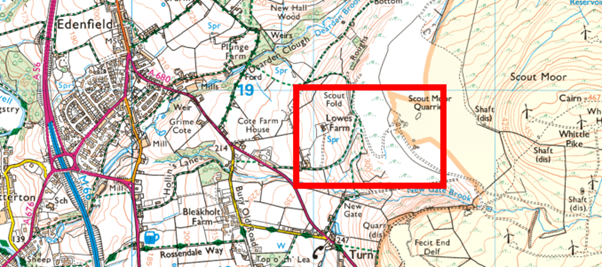

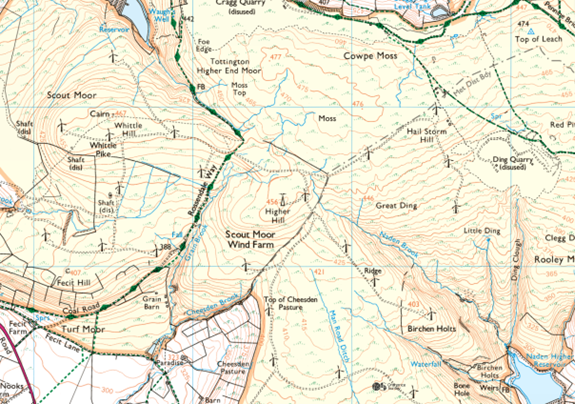

There is ground similar to Hoar Nib in the access to Scout Moor, but here the area had already been flattened by quarrying. The terrain and weather at Scout Moor were described as “exceptionally challenging” but both are worse on Walshaw Moor.

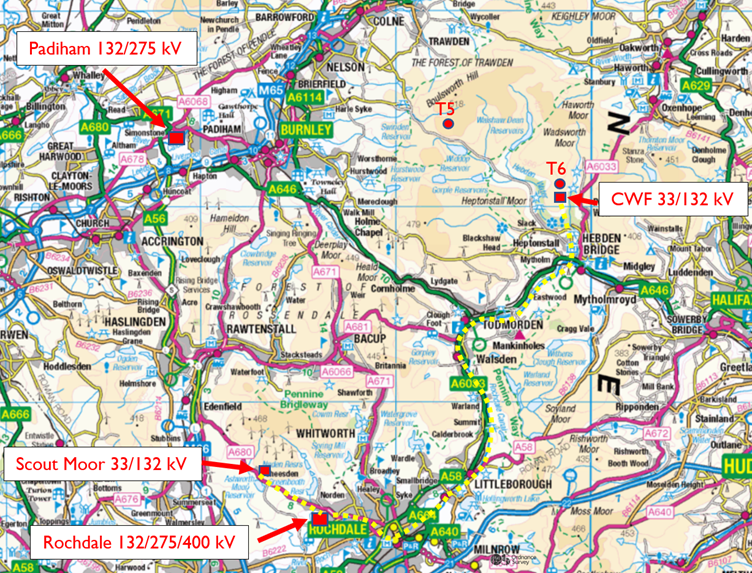

So, the only spine terrain with difficult gradients on Scout Moor was at the existing concrete hairpins up to the quarry. The M66 and A56 were immediately on hand for blade delivery and the map below shows the closeness of the Cheesden 33kV/132 kV substation for Scout Moor to the 132 kV/400 kV NG substation at Nordern on the site of the old coal-fired Rochdale Power Station.

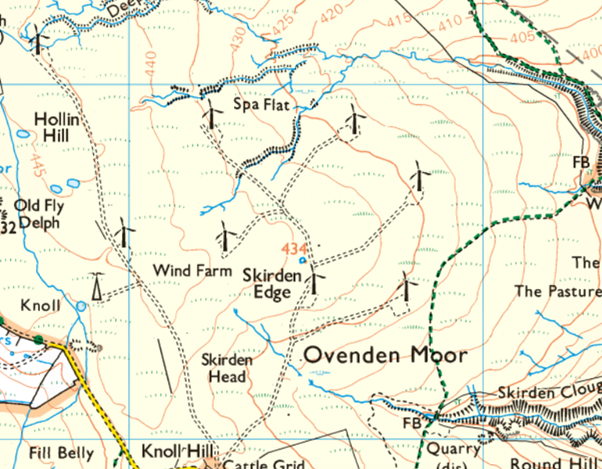

We see that Scout Moor was an easier engineering proposition than Walshaw Moor. Yet Scout Moor was itself regarded as a formidably difficult site compared to most wind farms. Compare the simplicity of repowered Ovenden Moor. The spine road had been built for the first version, and the connection to Bradford West already dug. The ground is almost flat, and the peat was destroyed already by the first wind farm. Despite its simplicity, Ovenden continues to be cursed by Emily Brontë. For two years now one of the nine turbines has been broken, an 11% loss of income that would perturb most households, but in the opaque world of wind farm financing seems not to matter at all.

Ovenden is admittedly small at 22.5 MW. Whitelee 539 MW south of Glasgow on the M77 shows how simple a vast wind farm can be if it is built in the right place. The site had been covered in sitka so had already been destroyed. Whitelee is vast but simple, and the terrain can be shown in a small section because it is all the same.

Whitelee has an onsite 33 kV/275 kV substation, and a 16.5 km cable connects this high voltage to East Kilbride South National Grid 275 kV/400 kV. Compare this serious set-up with CWF, which has a 132 kV substation in a house in Shackleton, where a family are presently living, and is registered to connect 170 MW to the local DNO down a 28 km trench. Transmission losses per km are quartered by doubling the voltage so are almost seven times greater down CWF’s long low voltage cable to Rochdale than in Whitelee’s shorter 275 kV connection. The 2023 Scoping Report says the CWF cable will be buried. They cannot afford to bury the 28 km cable of a 170 MW wind farm. The connection is subject to a separate planning application once the wind farm is approved, It will then be ‘discovered after further technical work’ that a buried cable is much too expensive and it will go on sycamore H-poles, at great inconvenience to people in Calderdale and West Lancashire.

Access to CWF from the motorway is so complex that it will probably have to be via Ovenden WF, and an extra access track will be cut through the deep peat on Oxenhope Moor to reach the A6033. Because it was already a developed forest, the Whitelee tracks required only 400,000 tonnes of crushed stone, all of which was quarried onsite. 170 MW CWF has no relevant tracks so it will also need 400,000 tonnes of crushed stone (and more than double this for 302 MW CWF) all of which which will have to be imported, because the onsite rock is too weak for roadstone.

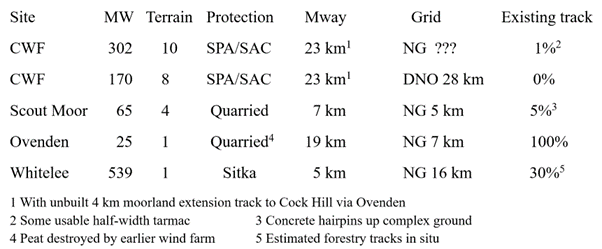

The access, weather, internal terrain, deep peat, weak rock and distant connection are all formidable engineering problems for CWF at either of the announced powers. No other wind farm built in the UK has all of these problems, and none to the extent of deeply divided CWF. In the table below I summarise these engineering and legal habitat difficulties. The UK onshore wind industry can solve all of CWF’s problems one at a time. No developer with a reputation to lose would bother to solve all of them at once, because reputable developers have first crack at much simpler sites. Christopher Wilson, the Executive Chairman of Calderdale Wind Farm is not a reputable developer because he has no reputation.

Of these wind farms, the one I’d want to have to have paid for is Ovenden. It was so cheap and cheerful that they can afford to run it with 11% of the turbines permanently broken. Compared to CWF, Whitelee was money for old rope, and even Scout Moor has the advantage of access and connection, and those lovely access hairpins already levelled. We are in the early stages of on onshore wind bubble and there will be many financially duff projects offered up to planning. CWF is one of them.

Note that the Walshaw Moor estate does not quarry its own aggregate because it wants its tracks to be strong enough to support an occasional pick-up, and correctly uses imported “blue granite” because its acidity matches the local rock. It may be that limestone tracks for CWF will be ruled out in planning in which case the imported aggregate must come even further. More stone will then be imported for the concrete, because the onsite rock when crushed is too weak and porous to make anything much more demanding than garden gnomes.

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

This is the 30th in a series of 65 guest blogs on each of the wind turbines which Richard Bannister plans to have erected on Walshaw Moor. Turbines 5, 6, 8, 9, 11, 14, 16, 17, 21, 25, 27, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 40, 42, 43, 44, 47, 53, 54, 56, 58, 62, 64 and 65 have already been described. To see all the blogs – click here.

[registration_form]