Alick Simmons is a veterinarian, naturalist and photographer. He lives in Somerset. He has written seven previous guest blogs here – click here. His Twitter handle: @alicksimmons

One element of the government’s 2013-2038 strategy – click here – to eliminate bovine tuberculosis (bTB) from the cattle herd (in England) is widespread, officially-sanctioned, privately-funded badger killing. The exact area involved is not published but I estimate that around 40% of England is under licence – an area similar to the combined area of the Kruger, Everglades and Royal Chitwan National Parks. In other words, it’s big.

You could be forgiven for thinking that 2013 was the beginning of badger killing. In fact, it started in 1973 although there have been several lengthy pauses while scientists cogitated and while policy was developed. You could also be forgiven for thinking that 2013 was the beginning of serious efforts to eradicate bTB. Again, this has a long history.

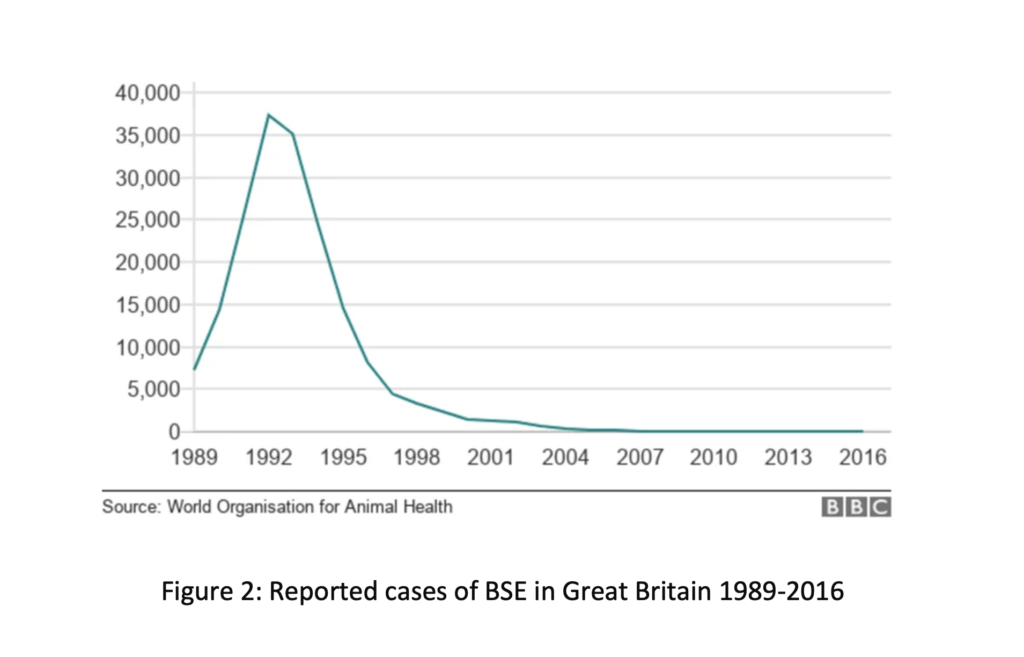

The first attempts to control bTB in cattle began in the 1930s although the real effort began after World War II. Which means we are not far short of the centenary of the beginning of bTB control in the UK – and it’s far from complete. Contrast that with 21 years it took for global eradication of smallpox and 20 years for the virtual eradication of Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy (BSE) from the UK. The latter two are very different diseases but it illustrates what can be achieved when an effective strategy is employed.

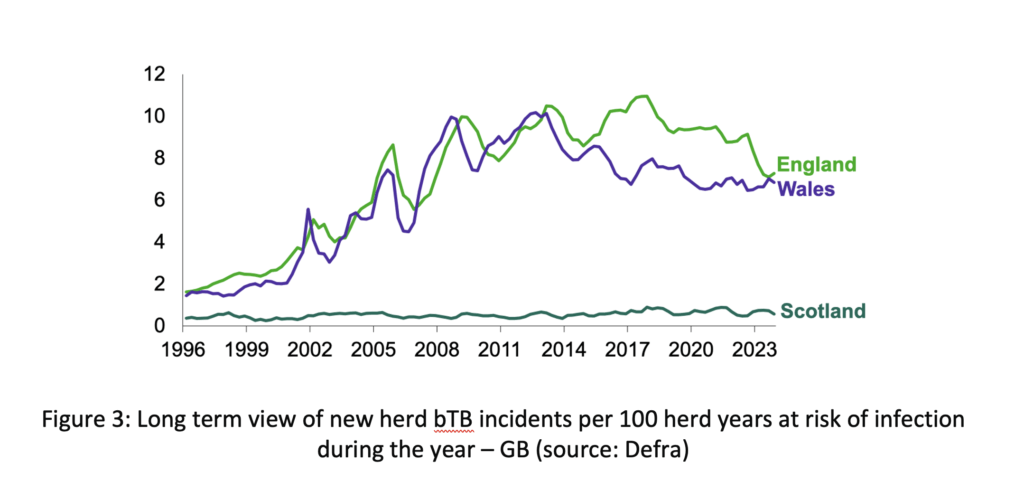

Is the bTB strategy effective? There is little doubt that widespread and protracted badger killing since 2013 has had an impact on the amount of infected cattle in England. However, the reduction, while statistically significant, is modest and interpreting the data is confounded by numerous uncontrolled variables. But the objective is not a reduction in infection or even a sustained reduction in infection, it is the elimination of the causative organism from cattle. And were badger killing and the associated cattle controls the only measures employed towards the objective of Official Tuberculosis Freedom (OTF) status by 2038, then it will almost certainly not be met. This is illustrated by comparing the epidemic curves for three diseases:

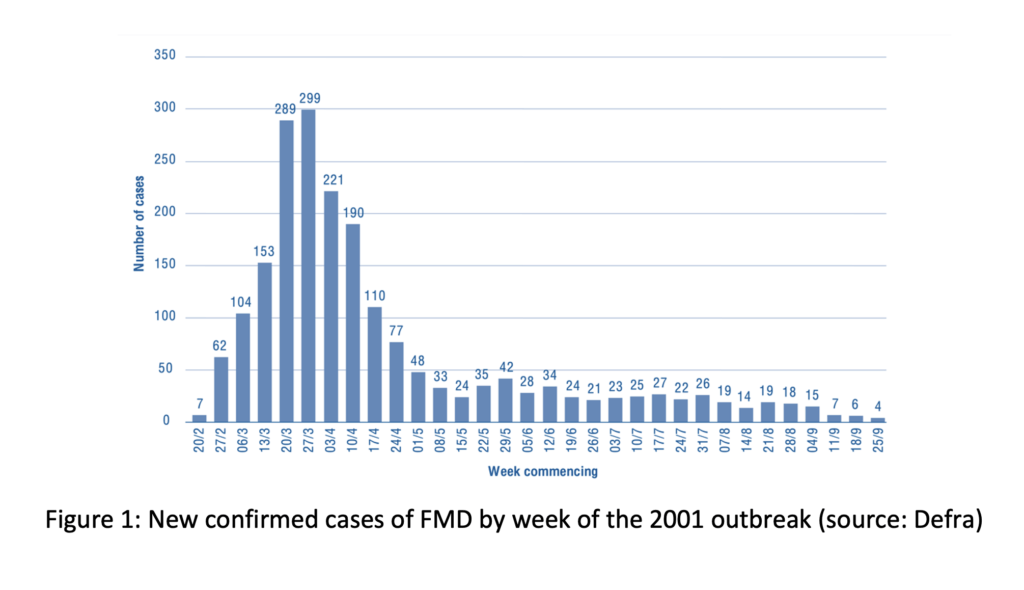

Figures 1 and 2 show the early steep decline in and eventual disappearance of new cases of, respectively, Foot and Mouth Disease (FMD) and BSE following introduction of an effective control strategy. In contrast, even when one takes into account differences in incubation periods and the staged introduction of badger killing, the decline in bTB as shown in Figure 3 is much less pronounced. The exponential reduction seen in the FMD and BSE graphs is missing.

Figures 1 and 2 show the early steep decline in and eventual disappearance of new cases of, respectively, Foot and Mouth Disease (FMD) and BSE following introduction of an effective control strategy. In contrast, even when one takes into account differences in incubation periods and the staged introduction of badger killing, the decline in bTB as shown in Figure 3 is much less pronounced. The exponential reduction seen in the FMD and BSE graphs is missing.

Perhaps it is the slow pace in the reduction in new herd incidents that is behind the government’s proposals for more draconian badger interventions – click here – in areas or ‘clusters’ now deemed to be even higher risk than areas previously deemed ‘high risk’. These proposals which are now out for consultation involve more intensive killing of badgers in specified areas followed with vaccination of what is left of the population. Increased cattle-oriented measures will also be introduced.

I’m interested in effective disease control and, where it is warranted, practicable and cost-effective, the eradication of the causal organism. And as an unashamed bunny hugger and a democrat, I’m concerned about the protracted war on wildlife and the exclusion of great swathes of the population from any say in the process. My thoughts on the proposals include:

- How will the clusters be identified and managed? Despite considerable detail, the criteria that will be used to define a cluster are not provided nor is it possible to determine the temporal and geographical extent of future badger killing or to determine how many badgers will be killed. One can only conclude that the intention is to allow for maximum flexibility of response. While accepting that disease control requires a flexible approach, often in real time, data from a decade of badger killing could have been used to introduce precision into the process.

- How will local extinction be avoided? The proportion of badgers killed hitherto in a given area is between 70-95% of the population; an increasing effort is likely to lead to 100% of badgers being killed in some areas. This would be a breach of Article 8 of the Bern Convention – click here – to which the UK is a signatory.

- What about the exit strategy? The consultation mentions an exit strategy but is silent about the criteria to be employed. How great does the reduction in the number of new herd incidents (and over how long a time period) need to be to decide that badger killing is no longer warranted? Similarly, once badger vaccination starts – assuming there are badgers left to vaccinate – how many years will it continue? How will success be measured?

- What is a landowner? The consultation promises to engage farmers and landowners where clusters are proposed. What is the lower threshold in land ownership? Does one need to own or occupy a certain area before being engaged or am I eligible by dint of my postage stamp of a garden ? Does the land need to be used for a specific purpose? Do those landowners that have previously refused to allow badger killing on their land get consulted? If not, why not?

- What about local residents? The consultation is silent about other residents in the vicinity of proposed clusters. Yet these proposals risk the local extinction of an animal regarded as important by many people. It is morally wrong to propose such draconian action while side-lining and ignoring the views of the majority.

Along with new badger measures, it is proposed to publish animal-level bTB risk information in an effort to support responsible cattle movements and purchases. Adopting this would be voluntary. Reducing the spread of infection from ‘dirty’ to ‘clean’ area by controlling the movement of susceptible animals is a pre-requisite for successful disease eradication. It is also essential to reduce the risk of introducing infection to badgers in areas which have not hitherto been affected. In previous successful eradication campaigns (eg Brucellosis) there were mandatory controls over the movement of cattle between holdings depending on the disease status of the herd. The government’s own analysis of the risk of spread of bTB infection – click here – states:

‘The movement of cattle with undetected TB infection is believed to be the most common way in which this disease spreads to new areas. In particular, movements of cattle from high bovine TB incidence areas of GB pose a substantial risk of introducing the infection to the lower incidence areas of England and Wales. Such movements account for more than half of all new TB herd breakdowns with lesion- or culture-positive animals identified in the LRA each year and about one third of such breakdowns in the Edge Area’.

Given the risk from cattle movements a better approach would be to protect the ‘clean’ areas of England by prohibiting the movements of cattle from the higher risk areas altogether. That is, introduce zoning in the country, a measure which has been effective in many other eradication campaigns in the UK and other countries.

________________________________________________________

While these additional measures may help to bear down on the infection in cattle a little more, the goal of OTF remains a long, long way off. Vaccination of badgers and, perhaps in time, of cattle may further help but each is some way off, unproven and expensive. Meanwhile, the wholesale killing of our native wildlife proceeds apace, and farmers continue to struggle with the impact of the controls on their businesses and the toll on their wellbeing. And the citizen continues to shoulder the £100m annual costs – and with little prospect of material change anytime soon.

One might ask, how did it come to this?

It is worth going back in time. Bovine Tuberculosis is a zoonosis – a disease transmissible between vertebrate animals and humans. In the 1930s the annual number of new infections of bTB in people was in the tens of thousands. The vast majority of these cases were contracted from the consumption of raw, infected milk – around 40% of dairy cows were infected, frequently severely. This alone was reason enough to tackle the disease. The introduction of routine testing virtually eliminated severely affected cows and led to a greater and greater number of accredited, infection-free herds but the real agent of change was the adoption of heat treatment (commonly known as pasteurisation) of dairy products. The primary benefit of heat treatment was an improvement in keeping quality but another benefit was the elimination of zoonotic organisms like Leptospira, Brucella and Mycobacterium bovis, the bTB organism.

Cases of bTB in humans in the UK now number around 30 cases per year with most of these believed to have been contracted overseas – click here. Contrast this with Campylobacter infection, a particularly nasty zoonosis and one which is closely associated with the consumption of chicken meat: Around 300,000 human cases of Campylobacter are estimated to be acquired from food each year in the UK – click here.

The zoonotic risk is frequently cited as the reason for seeking to eliminate the infection in cattle. True, the potential hazard remains but if the risk is managed and has been managed for 50 years or more, why does the taxpayer need to spend hundreds of £millions particularly when the chances of attaining OTF seem so small? Nothing approaching £100m is spent on Campylobacter, an infection that causes a great deal more human disease than bTB.

Regular testing means that clinically affected cattle are vanishingly rare so the direct impact on production and animal welfare is minimal. The biggest impact of bTB on farm businesses comes from the effects of official controls: movement controls, the loss of cattle slaughtered compulsorily and the costs of repeated testing – not the disease itself.

Since the early 1970s, the government has commissioned several independent reviews but these have always been conducted by scientists working to tightly worded terms of reference. Given the intractable nature of this infection, the costs to the taxpayer, the impact on farms, farmers, wildlife and the general public perhaps it is time for another type of review – examining the issue from a little further away with a brief like this:

‘To advise the Government on the most appropriate policy for bovine TB taking into account the public health risk, the economic impact on the farming sector, the threat to native wildlife and the cost-benefit of intervention.’

To be clear, I don’t advocate giving up but an objective examination of the evidence, costs and benefits might signal a way of managing the risks at lower cost and lower impact while still controlling the disease. And instead of a forever war on wildlife in pursuit of the unattainable, the money might be diverted towards something with real health benefits – like a new hospital or two.

[registration_form]

Dear Mark, a very interesting blog post but not sure of the accuracy of: ‘There is little doubt that widespread and protracted badger killing since 2013 has had an impact on the amount of infected cattle in England.’ From all the research I have read it seems this would be impossible to actually prove this beyond doubt.

Of great interest was your analogy with Campylobacter infection. I have long thought the policy was a sledgehammer to crack a nut (www.bovinetb.co.uk). See also ‘Public health and bovine tuberculosis: what’s all the fuss about? ‘ (Torgersons) and Rethink bTB https://www.facebook.com/search/top/?q=Rethinkbtb&locale=en_GB

Sally – thank you for your first comment here. Not my analogy – it’s a guest blog by Alick Simmons who, by the way, was once the Defra deputy Chief Vet.

I agree with Sally completely, and funnily said much the same before reading her reply!

Thank you for responding, Sally. The evidence that protracted and widespread badger killing has an effect on the prevalence of bTB in cattle is irrefutable. Thus, it provides a measure of control – provided it is combined with effective cattle measures. However, as a method of seeking to eliminate the infection from cattle it is ineffective. Irrespective of your and others’ position on the ethics of killing badgers, I don’t think it helps to ignore this.

I am clear that the current policy won’t work and thus we should stop killing badgers. But stopping without an alternative policy would be irresponsible which is why I advocate an in-depth policy review.

Alick writes a superb article – as would be expected – he knows what he’s talking about. And I am so glad that he points out, as I have done too many times, that badger control did not begin in 2013!

As some may know I’ve been closely associated with badgers and bTB for many years, in fact most of my adult life (and I am pretty old!). My only departure from Alick’s view is the comment “[t]here is little doubt that widespread and protracted badger killing since 2013 has had an impact on the amount of infected cattle in England.” From my own observations and studies, I’ve long concluded that badgers present a infinitesimal risk to cattle. I said so in my 1986 book (The Fate pf the Badger), and I still believe so today.

Alick, of course, has no alternative but to concentrate on the badger since this is the focus of government policy, but it blinds us all to the fact that the badger, due to its size, history and habits, is an easy target but it is by no means the only carrier of this insidious pathogen. Many animals – domestic and wild – are susceptible and theoretically capable of infecting cattle (and each other), but none is as convenient a target as the badger.

The microscopic tubercle bacillus does not differentiate by size or habit of host and is not interested in politics or economy. The only way it can be meaningfully defeated is by an effective vaccine for cattle (just as for us): thus, at a stroke, the problem disappears. It is endemic across the countryside, and whatever farmers and Defra claim, as a disease in wildlife it is self-limiting.

I am surprised to see this contribution by Alick Simmons to Mark Avery’s previously excellent discussion of the unscientific, expensive, cruel, and ineffective attempt to control bovine TB by culling badgers to extinction in parts of UK. Simmons states “there is little doubt that widespread and protracted badger killing since 2013 has had an impact on the amount of infected cattle in England” when the doubt is not only huge but is leaning towards badgers not being involved to any significant extent at all. He talks of the “introduction of routine testing virtually eliminat(ing) severely affected cows and lead(ing) to a greater and greater number of accredited, infection-free herds”. He does not mention that SICCT testing is hopelessly insensitive, nor that residual latent infections can develop into the infectious state. He states that “regular testing means that clinically affected cattle are vanishingly rare” but does not mention that while prevalence of OTF-W herds is reducing, OTF-S prevalence is not. He questions whether “it is the slow pace in the reduction in new herd incidents that is behind the government’s proposals for more draconian badger interventions” and mentions Defra’s consultation on epi-culling, or low risk area culling, without referring to the strong independent scientific evidence against this approach. He should also have said that the consultation is biased, flawed, contains leading questions, and is currently undergoing legal challenge. Simmons does not “advocate giving up (on killing badgers) but (requests) an objective examination of the evidence, costs and benefits (which) might signal a way of managing the risks at lower cost and lower impact while still controlling the disease.” The single most effective solution to the bovine TB problem would be to employ more sensitive diagnostic tests to identify and remove OTF-S cattle, but it seems that DEFRA are simply not prepared to objectively examine or act upon any independent evidence.

What an odd response.

If you going to quote me the least you could do is not edit the quotes to suit your own agenda.

And for the avoidance of doubt, I am well aware of the performance of the SICTT having personally tested many thousands of cattle. Despite the poor sensitivity of the test the fact the remains that routine testing and removal of reactors means that clinical cases of bTB in cattle are vanishingly rare. In 40 years neither I nor the team of veterinarians under my management ever came across a clinically affected bovine.

Thank you for your response, Richard.

As I left public service 8 years ago, I have every opportunity to express an alternative viewpoint, hence this blog post. I am not beholden to my former employer.

I note your comment about the contribution that badgers make to the spread of bTB – see my response to Sally above.

I do rather worry when I read unsubstantiated statements such as “There is little doubt that widespread and protracted badger killing since 2013 has had an impact on the amount of infected cattle in England.” In such a prestigious and influential blog. This undoubtedly labels badgers as a guilty party when this is far from proven, within a maze of other interventions, typifying the sort of conciliatory, caveated statements to pay homage to DEFRA. Historically, one of the worst, ““The farmer was conscious of the role played by wildlife” and then “A large proportion of reactors showed visible lesions at post-mortem examination and there were clear indications that wildlife was playing an important role in the maintenance of the TB cycle in this herd.” All completely subjective propaganda, in describing how a farm went clear, after extensive gamma testing and the advice to stop feeding their calves on raw unpasteurised milk, pooled from the entire herd.

I am currently involved in an in-depth study of Devon cattle and badgers and can tell you that alongside the 40.917 badgers now killed, more to come the cull has not finished. In Devon between 2013 – 2021, in the cull zones area they have removed 37,531 cattle skin test reactors. However, over the same period a further 10,032 otherwise unfound gamma reactors were removed. With disease of such prevalence within the cattle, given that cattle live with other cattle, why on earth are they so hung up, blaming and ridding our countryside of badgers with what can only be, in comparison, if at all, a minuscule risk.

To be clear, I oppose the current badger killing policy. That is, I contend, obvious from the article. I also believe that I would be unlikely to find myself supporting it if it were proposed under another policy. However, there are several peer reviewed scientific articles drawing in data collected from the RBCT and the current policy which supports the statement in my article.

In my professional civil service career and in the work I undertake now, paid and unpaid, I draw on evidence to develop my position and to support statements I make, whether verbal and written. However abhorrent I find badger killing, it would be disingenuous and unprofessional to state that badger killing has no effect, because it does.

My contention and the subject of the blog post is that the current policy will reduce the prevalence of infected of cattle herds, but it will (even when combined with other measures) NOT lead to elimination of the infection cattle – the objective of the strategy.

The strategy is too expensive, too weak on cattle controls, treats hazards as risks, too disruptive to farmers, excludes the general public from any influence and is hence likely to fail. Which is why I advocate a detailed high level policy review.

Just because you oppose it doesn’t mean you haven’t written something that enables it. Honestly, sometimes I wish more campaigners would take a media literacy course once in a while. Learn how to write an article that empowers their point of view instead of enabling their opponents. Take a page from the Tabloids’ book (although not number 3, please) and earn how to set up the campaign point of view from the headline on down, all the way to burying anything even slightly confusing in the final paragraphs.

Good grief.

Perhaps if you’d bothered to read and understand the entire post then you’d have appreciated a little of the complexity of the issue.

In the words of HL Mencken ‘ For every complex problem there is an answer that is clear, simple, and wrong.’

And I might be more inclined to take you seriously had you not chosen to hide behind an anonymous ‘handle’.