This is a book that many people ought to read. I read most of it before I went to the USA and then read all of it, some of it several times, on my return. I was reading it again at 6am yesterday morning in the back garden of the Old Mill Hotel in Salisbury where a kingfisher, a juvenile robin and a loud wren distracted me.

I agree with the thrust of this book – which I believe is that we need more wild nature in our lives and that we ought to put it there through ‘rewilding’ some of the world around us. That’s a good message and is almost becoming nature conservation orthodoxy in the UK. Some of the questions that remain are; how much? how? where? and how quickly?

What is this thing ‘rewilding’? It’s restoring ecosystems that are largely unperturbed by our own species, including restoring some large and locally extinct species such as wolves and white-tailed eagle.

Monbiot suggests that we are all missing the wilder life and discusses people’s keenness to ‘see’ large black cats running around the British countryside. We need more forest, more wolves, more beavers, fewer sheep, less fishing of the seas and we need the policy makers either to stand aside or to adopt this as a basis for public funding of land managers, but we shouldn’t oppress the landowners if they don’t fancy the prospect of change.

There are some lovely bits of classic Monbiot. He has a go at farming unions for talking rubbish and the CAP for being rubbish. Monbiot writes, ‘ …the CAP stings every household in the UK for £245 a year. That is equivalent to five weeks of food for the average household, or slightly less than it lays down in the form of savings and investments every year (£296). Using our money to subsidise private business is a questionable policy at any time. When important public services are being cut for want of cash , it is even harder to justify.‘. When Monbiot from the left of politics, and Roger Scruton from what looks like the right to me (in Green Philosophy), both criticise the CAP on similar grounds there seems no place for the discredited implementation of a European ideal to hide.

This book has quite a lot of how Monbiot feels about nature, what he enjoys doing in Wales, and anecdotes and instructive stories from his past in a variety of locations outside of Europe. These didn’t help me very much in following the argument nor did they work that well in keeping me interested – they may work brilliantly for you, of course, as those things are very personal in nature.

It’s not obvious, to me, whether Monbiot thinks that this re-wilding idea is ‘the’ way to do nature conservation or ‘a’ way to do nature conservation. If the former then he is wrong, if the latter then he is right. Many species, including declining species, rely on farmed landscapes for their existence and we shouldn’t abandon them and their needs (for example) while we wait for an overgrazed hillside to grow into an ancient woodland.

Monbiot is not over-generous in referencing the steps that many conservation organisations, and indeed individual landowners, are doing in the fields of species reintroduction, habitat restoration and habitat re-creation – there is quite a lot going on, it’s difficult work and it’s very expensive too. But if his book brings the message of how much nature we have lost to many more people, and persuades them that we might be better off mentally, physically and even financially, if we brought back more wild nature then it will have done everyone a service.

Monbiot largely leaves it to others to work out how to get from the mess we are in now to his rather unspecified better world. That’s fine, but it does need doing.

Really wild places will have to be really big to be really useful. There is no point, or not much at any rate, doing a bit of tinkering. I’d love to see us re-flood The Fens, or some of them anyway, and bring back a living wetland that would store carbon, produce fish and other food and act as a wetland National Park for East Anglia. I would love to see much of Salisbury Plain return to chalk grassland and low-intensity arable farming with masses of butterflies and chalk grassland flowers (and great bustards of course). With good rail and road links from London this could become a weekend destination for re-wilding addicts fleeing the big city. Let’s see large parts of upland Wales return to deciduous woodland with bison in the woods and bison-burgers in the pubs.

I’m up for all of these, certainly after a drink or two, but in the cold light of day you can see that there might be a few sugar beet and carrot farmers in Cambridgeshire who are a bit less enthusiastic about the first; some arable farmers un-keen on the second and the odd Welsh sheep farmer who is concerned about the last one. And that’s a large part of the reason why they haven’t happened yet – not because nobody thought of them but because we were all too scared to push them as hard as they need to be pushed and for as long as they need to be pushed. Maybe Monbiot’s book will stiffen the sinews and summon up the blood and we can go back into the breach again.

Any book that the President of the NFU hates must have something going for it and this book really does have a lot going for it. It didn’t, it seems, open Peter Kendall’s mind to future prospects of exciting wild lands but your mind might swing open more easily. Read it – it should enthuse you about the possibilities of the future, but it certainly isn’t a road map for getting there.

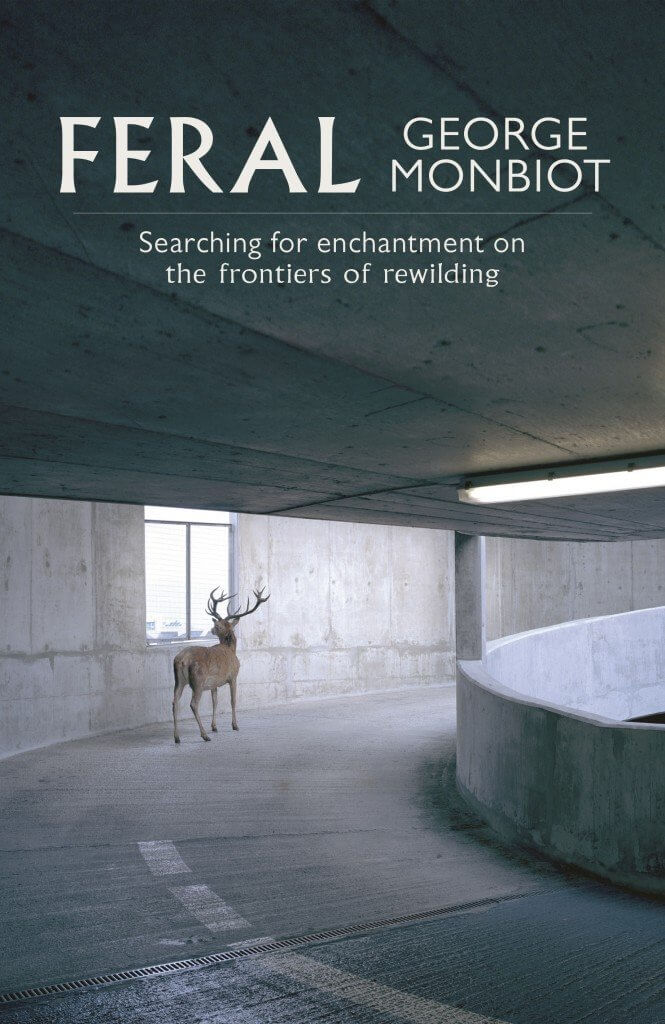

Feral: searching for enchantment on the frontiers of rewilding by George Monbiot is available on Amazon as is Mark Avery’s book Fighting for Birds.

This blog is going to feature book reviews, mostly of newly published books, on Sundays for the next few weeks.

[registration_form]

Morning Mark – I did want to pick you up on one thing. When I was trying to persuade Forestry Commission in Wales to use blocks of unprofitable woods to introduce European Bison in Wales as you describe the officials were listening. What stopped the idea in its tracks was the Wildlife Trusts who did not have the stomach to face up to the obvious criticism that would follow.

It is the conservationists who have to agree to follow the “rewilding agenda” first before we get anywhere. Sadly I fear they do not have the balls!

Derek – good morning. Thank you. Am looking forward to reading your book and reviewing it here in future. When is it out and what is it called?

Of course there is justification on cutting the payments to the either rich or large farmers but what about all the smaller farmers who rely on this income to survive and give us a relatively nice landscape to live in.

It must be the easiest thing in the world for a relatively rich person like G M to criticise something that he hates but is essential for small farmers also of course as we are part of the E U we do not have much say in it.

Of course it also gives G M a chance to make more money doing articles on it that he knows are irrelevant but enhances(not mine)his following.Seems to me once you become a relatively well known journalist people follow your thoughts like lemmings.

Most of those receiving these payments work longer,harder than G M producing practical things such as food that everyone needs and even G M benefits from.They also would think all their xmas’s had come at once to receive anywhere near his income each year.

Yes G M the world is not a fair place but you are certainly one of the privileged few.

To be fair, in the book Monbiot dedicates a chapter to his experience with a small-time farmer in Wales, who he is very complimentary of and stresses the importance of farming culture in this sense to persist. He doesn’t advocate for getting rid of subsidies; his solution is to stop subsidies increasing above a certain large estate size, but mainly to remove regulations which state landowners have to clear vegetation and keep land ‘tidy’ to qualify for subsidies. His argument is this would allow small-scale farmers to continue, but large landowners, particularly non-resident ranchers, would realise it made more economic sense to just leave the land alone, thus allowing ecological recovery

I have not read the book, so can’t comment on it……

But 2 things taken from your piece: firstly one of the “good” by products of army ranges appears to me to be keeping us lot (human hoards) out.

Secondly, I wonder if population is addressed in the book? I hope it is, because the problem with taking farmland completely out of production is feeding us, yes us human hoards. These little islands need far fewer people and addressing that is the fundamental issue.

Having said that, wild empty places (empty of people) are the most wonderful bits of our little set of islands, if you can find them.

Try sitting out listening to a dawn chorus, now get the recorder out and listen to the planes wrecking it!

yes the mod keep the riffraff out quite effectively with all those red flags fences and explosions and the juniper population on porton down is quite impressive as a result however if you are expecting watermelons to address matters of population please remember to breathe when your lips turn blue and in particular don’t expect any such debate from gurniard journalists for whom such stuff is off-limits and who are more concerned with somewhere nice to park their volvos

Hi Mark! The book is simply called Birds: Coping With An Obsession. It is out on August 1st and you will be getting one.

good arrow dennis

for moonbat it matters not that a very large proportion of our food is imported and this would get worse if he had his way although that is only a bad thing according to dinosaurs like me who are regarded as economically naive by brown balls economists who remember are responsible for the straightened times in which we live but never mind all that it is true for a large proportion of farmers that their business activities are in the red and their black income is derived from subsidy which situation has a lot to do with the cynical exploitation of trading conditions by the supply chain to deliver cheap mince at the point of retail sale so in effect subsidy is de facto income support for farmers and as we know income support is a human right in the eyes of dreamers and arm wavers so it puzzleth me that moonbat is so against it giant intellect that he is except when twittering which as any fule kno is not possible with the brain engaged

Just before reading this review I came across my notes from 2002 when the Forestry commission was framing ‘Wild Ennerdale’ – some of us have been at this rather longer than George Monbiot and I very much agree its been a lack of imagination – and over reverence to man-made barriers, all be it substantial that is stopping new ideas developing.

George Monbiot makes the common mistake – dramatic carniroes, the remote uplands. the lowlands, are of course, reserved for the East Anglian carrot farmers. Complete Rubbish. We need nature close to where everyone lives. Rewilding, also, ins’t just about nature – again, conservationists have been slow in recognising the ability of land to do more than one thing at a time (as, too, have most other land users). Lower intensity land use near where we live can work for water – flooding and supply – for wildlife, for quality of life – health, reconnecting with nature. It might even produce useful fuel – from trees and reeds – and small scale production from allotments is amongst the most effective forms of food production.

But of course you have to pay for it – again, no problem – as Monbiot points out we already are, and as I’ve iaid many times before I agree with Dennis – land managers should be paid. The difference is they may need to accept payment for things the rest of us want, not just to go on farming the same old way. And to top it all off John Krebs’ climate change committee has just pointed out that water supply looks like being critically limiting for farming as the climate warms – and nowhere will that hit harder than in East Anglia – so flooding a large part of the fens may be crucial to keeping the rest productive, at the same time absorbing flooding ina a way adding another metre or two to flood banks of the Nene Washes never will.

Rod is right on the nail here. Many of us have been wrestling with rewilding long before Monbiot got hold of the idea. I always hoped we could do it in partnership with land owners and the farming fraternity. Outright confrontation and leaving it to Government is a non-starter.

I look forward to an interesting read especially with pre advice from this site. As regards Roger Scruton, I have also ordered that one from the library. I don’t like the concept of left and right but I do recall a radio programme a few years where Roger Scruton was arguing very strongly that animals have no rights. Philosophical or not what follows must be that no rights means no need of protection which means no harriers. I therefore look forward to his arguments on assuming responsibility for the environment.

The fact that ‘Wild Ennerdale’ can’t even reintroduce Pine Marten says a lot for such programmes when it is costing the tax payer £millions in ‘Red alert’ when wild species can do the job for them. A brilliant read even if some people can find faults in it.

Well I’m surprised you went all the way to The Old Mill and didn’t mention its location at the Harnham Water Meadows:

http://www.salisburyvision.co.uk/page/Harnham-Water-Meadows/59/

Bentley Woods are a good place for Purple Emperors apparently although that would change if all them nature tourists start coming down here to gawp at them.

filbert – you will hear more later this week…

I’ve not read his book yet, but he has an article in this month’s BBC Wildlife magazine. Like you, I think the idea of rewilding is a great idea, but I do wonder if the scale that he seems to suggest is something that’s not likely to take off. In his BBC Wildlife article, he refers to pre-agricultural British Isles as a model for how he sees the way our landscapes should be now.

I don’t think this will be allowed to happen because of a few reasons:

* landowners and farmers will not allow their land to be molded and changed, especially when they currently profit from the way they use their land now, whether that be for sheep, crops or shooting

* the conservation bodies would need to have a change of approach to the way land is managed. Monbiot proposes that land is not actually managed per se, more that we would give it a helping hand at the beginning: blocking drainage ditches; removing sheep; removing fences; planting trees; reintroducing species, e.g. beavers, and then later, moose, lynx and other charismatic megafauna. With our landscapes drastically changed since pre-agricultural times and conservation bodies being responsible for looking after the species living here now, would they countenance the disappearance of these species to bring back species from 6000 years ago? Are some species here now only because of the way land is managed now? For example, the many species that live on or around farmland – tree sparrows, yellowhammers to name two – what effect would rewilding have on them? How do they fare in other parts of their ranges, e.g. across mainland Europe, and do they live in more “natural” environments there?

* many members of the public will be fearful of a countryside that may include species like wolves and large herbivores like moose and bison, and these could be a force against these proposals, especially when they get sympathetic MPs on side to argue against the proposals in parliament

* when people can walk from Glasgow to Fort William (about 94 miles) in about 5 days along the West Highland Way across some prime potential habitats, it suggests that our country is really small and wouldn’t provide enough space for large species that require large territories, especially when the space given to them will be highly limited by landowners etc.

Now Monbiot gives the example of the wolf reintroduction in Yellowstone as a prime example of how rewilding can be done right. These wolves came in and began controlling populations of large herbivores. This allowed trees to recolonise. Beavers started using these trees to create their dams and for food, altering the courses of rivers, which led to new habitats being created for other species. It has been a monumentally successful scheme and I for one would love to see something like it in the UK, but with so many forces against the concept, I wonder if we’re ever likely to see such large scale ideas come to fruition?

John – that’s a great comment – thank you.

The well-known Yellowstone wolf story is a good one. And I have seen wolves in Yellowstone and they made my day. They don’t thrill everyone though and the wolves don’t respect the Park boundaries.

Yellowstone is nearly 9000 square kilometres – about 93km square. That wouldn’t be far short of Inverness- Fort William – Dundee – Aberdeen – Inverness again. If we left out those four towns it would make quite a nice National Park with around 150 wolves perhaps. I’d go for that! I guess we’d better ask a few people who live there before we let the wolves out though…

Wild empty places (Mark W). The other option is to move everyone out of Wales, knock down the bridges on the Wye and put in a fence along North Wales. That would give a Kruger sized National Park.

No, I am not sure this concept would work. Whilst Iolo Williams would be happy that action was being taken, only the animals would be entitled to free prescriptions.

I found my head nodding at Mark W’s comment but he also failed to mention with an increasing population where do they go in G M’s vision, nevermind feeding the ever increasing population.

You’re right about the opposition faced, look at the Fen project and the opposition faced and that was just for habitat restoration. Can you imagine wolves roaming around the countryside of the UK, you’ve all seen the hype about foxes imagine the hysteria with wolves, look at the opposition faced by Alladale in Scotland who wanted to re-introduce wolves in Scotland, how far did that project get?

Also if people are willing to trap/kill/poison something like a Golden Eagle or a Buzzard what future for something like the wolf? Won’t ever happen, sorry.

Haven’t read Monbiot’s book yet, but I was intrigued by your lyrical vision for Salisbury Plain. Yes, it would be lovely to have lots more great bustards, but realistically I wonder how they would cope in a re-wilded environment. Whatever gloss one puts on it, the re-introduction project, which one can’t help but support as an engagingly romantic idea, has frankly been a bit of a flop. Predation by foxes (and badgers?) has been chronic, and breeding success has been minimal at best. I can’t believe their chances would be any better over a greater range and with the introduction of larger predators.

Lazywell – I’d be quite happy with the stone curlews, grey partridges, chalkhill blues, dark green frits and acres and acres of chalk grassland flowers. great bustard would be a nice optional extra though.

I have now read the book, and like Mark, found a lot of meandering around a fairly basic premise. The meanderings were interesting enough, but as many have pointed out it’s about what a lot of conservationists have been doing for a very long time. The main difference is that GM is advocating big mammals (mostly). My feeling is that if we can’t keep what is already here, and cannot conserve invertebrates (look at decline in large insects) should we be worrying about bison or wolves?. My big criticism is however, who will make the decisions as what is an undesirable alien (which GM says we may have to get rid of knotweed, mink etc) and who decides which stay as part of the ‘rewilding’? All a little bit to hypothetical for me — need to actually do something, and I am not sure the uplands of Britain are really worth worrying about. Even the largest projects likely to get off the ground are small by the standards of the rest of the world. However, I do share Georges objections to ‘Mesopotamian’ mammals in the wrong place– though my aversion is to foreign aid goats! Worth a read.

If there is a significant ecological advantage to having packs of wolves roaming round the countryside killing stuff – why isn’t there a parallel advantage to having packs of hounds roaming round the countryside killing stuff?

“Many species, including declining species, rely on farmed landscapes for their existence and we shouldn’t abandon them and their needs ”

Which begs the question, how ever did nature cope before humans came along?

I have yet to read Monbiot’s book, but I am interested in the idea of rewilding.

And I find it interesting how conservationists in Britain react to the rewilding idea, and the room for disagreement. The conservation industry’s attitude to land management, seems to be that land left to nature and natural processes is “neglected”, and requires non-natural disturbance to keep it in a “favourable state”, which results in halting succession to the climax community (in almost all of Britain, woodland).

An example of a management strategy that I can’t get to grips with is releasing non-native cattle to maintain a completely unnatural habitat by grazing away at most of the veg. And at the same time the reserve manager is worrying about the atrocities carried out by non-native invaders/ native deer diets. Are these voices for nature or voices for more low-intensity farming?

I understand the argument for open space habitats for those species that need it, but were the populations of those species only so high because of the extensive level of farming that destroyed the natural habitats in the first place? When we’re fretting over depleted beetle populations, I believe conservationists ignore the elephant in the room – that the natural habitat and much of our native fauna remains missing from Britain. Instead, efforts are made to continue our exploitation of the land, and fret over the little we have left.

Goran – welcome and thanks for your comment. You should read Monbiot’s book – it is very interesting. But that isn’t the ‘conservation industry’s’ attitude to land management.

Rewilding can only part of the solution because of the constraints from land ownership and use and roads. BUT an even bigger problem comes from the eutrophication and warming of the countryside as a result of burning fossil fuels.

Large mammals may be able to thrive in the increasingly luxuriant vegetation and may be mobile enough to cope with a changing climate. However a great many more species will drift towards extinction – species dependent on bare ground, open habitats, low nutrient soils, cool streams, temporary ponds, and dozens of other highly specialised habitat features. Our pollution means that these features can no longer be relied upon to simply emerge from the land where we retreat.

If the aim is genuinely to ensure that there is space on the planet for other species to survive then unfortunately the maintenance of existing smaller scale features and the creation of new ones is likely to be a continuing tennent of any effective conservation strategy.

Newly created habitats tend to be homogenous and good for widespread generalists. It would be a difficult bit of accounting but it would be interesting to calculate the area of land that would need to be rewilded to have any hope of creating the array of habitats and features that are required by a half decent complement of species, work out how much this would cost in terms of lost income from the land and compare that figure with how much it would cost to look after what we still have properly and make smaller, more carefully targeted increases in the area and quality of the habitats supporting the most threatened species. I suspect that the latter approach would be much cheaper than rewilding.

Does George address these issues Mark? If he does I will get the book, if not then it does not qualify as a serious attempt at a conservation philosophy, more a recreation concept, a modern Royal hunting park idyll for the masses.

Rewilding, eh? What a jolly, jolly wheeze. If only some vague account was taken of what’s happening with climate change. Forget the jolly carnivores and big browsers and please wake up to the fact that we’re soon going to be needing to airlift populations of the once common, tiny things northwards – if we’ve actually managed to restore, connect and recreate adequate patches of habitat to receive them in the interim. I’d very much like to be proved wrong but looking back over the last 60 years and forward over the next 30, I am tempted to wonder if any bookie is offering a spread bet on the number of current species of conservation concern will still be in more than 3 counties by 2020. Hmm, perhaps with my winnings I can buy the Centre for Ecology and Hydrology which NERC seem to be willing to sell off (Oh, you weren’t aware of that? Have a look Here ) and employ its scientists to research subsequent bets. I do like positive feedback loops. For those not in the know, the Biological Records Centre – which works very closely with volunteer recording schemes and societies (remember that ‘call to arms’ State of Nature Report ?) is part of CEH. Of course, supremely daft though selling off CEH and other institutes to the private sector undoubtedly is, there is a brief frisson from thinking about how it might be kept within the public sector but merged with the EA,NE, & FC delivery bits. And in case you don’t remember back that far ITE (now part of CEH) was what was split off from the original Nature Conservancy.

Strange institutional fantasies aside. I would suggest ‘Rebugging the Countryside’ would be an ambitious enough step forwards at present (as well as anagrammatically, at least, addressing what’s been done to our largely man-made but still, in parts, wondrous, curate’s egg of a countryside over the last 60 years).

It would probably also be a good idea to be able to judge what was in the scales (and who had their thumb where) when the ‘over-riding public interest’ is assessed by ministers in relation to the irreplaceable remnants of historic sites and priority habitats. Meanwhile, based on the new Dogger Bank MPA, that nice Mr Benyon thinks that we now lead the world with our conservation efforts. How nice.

When did you last see a Tiger moth? Let’s at least ‘Save the Tiger’.

Hi Mark,

Like you I have bought and read George Monbiots book whilst we had a two week

holiday in the Cairngorms area recently. I agree 99.9% with what he says in his book

and I am sure it has got up the noses of a lot of people in particular farmers and the

landed gentry. This lot are still in the middle ages as far as conservation is concerned

I am sure they think like lords and want to treat the rest of us as serfs. Georges book stresses time and time again about leaving nature to herself and allowing a

gradual change to the landscape. Will his ideas take off we can only wait and see,

Even agencies like English Nature and The Scottish Natural Heritage are nothing more than toothless tigers who have been put in place to make the government look like it gives a damn about the environment when it is obvious they don`nt

give a toss. The latest plan to release lynx in the wilds of Scotland will be shot down in flames when it comes before the SNH for appraisal later this year, you

can bet the politicians are in league with the farmers and landowners to make sure it never gets of the ground. In G. Monbiots book the RSPB and other like organizations are also shown to be very poor and lacking any real clout. The RSPB

has over a million members but appears terrified to rock the boat, farmers,gamekeepers and landowners even the government should be scared of

them but of course they do not and we carry on the same tired old way which suits the few and not the many.

Regards,

Oliver Craig

I bought it.

Read it all.

Agreed with many of its notions.

Found it tainted with the nauseating whiff of moonbat in general though.

Noticed a mistake on page 6.

Contacted him about it.

He did respond, but in the manner of a spoiled child – some have said to me that sums him up.

I suggested to him he seems to have betrayed (cautious) zoology for (sensationalistic) journalism.

He didn’t respond again.

It is now on top of the cistern.

You know…. I can’t work moonbat out….. occasionally I agree with him, then he goes and makes my skin crawl all over again.

I think I expect better from an Oxbridge zoologist.

I guess thats the problem.

As for Peter Kendall’s thoughts on the book – I certainly do agree with moonbat here…. the president of the NFU either hasn’t read much beyond the title or he fails to grasp the basic messages contained within.

No.

I don’t care which it is.

I enjoyed reading it. It made me think…a lot.

Like you Mark, I agree with the central thrust of the book, especially when applied to the future of some of our upland regions, particularly the Scottish Highlands.

One thing that strikes me about George Monbiot is the fact his ecological education was centred on the tropics, he spent a number of years working in Indonesia, South America and East Africa. As he states in the book, ‘The lesson I learnt repeatedly, in all three regions, was that much of the diversity and complexity of nature conservation could be sustained only if the levels of (human) disturbance were low…’

Undoubtedly this has shaped his perspective and maybe explains his lack of appreciation for plagioclimax habitats and sniffy view of the nature conservation organisations and landowners that manage them. Statements such as, ‘I do not object to the idea of conserving a few pieces of land as museums of former farming practices, or of protecting meadows of peculiar loveliness in their current state, though I would prefer to see these places labelled culture reserves’, I found condescending and slightly at odds with his view that rewilding should not replace attempts to change the way farms are managed for wildlife. Make your mind up George!

However, if his lack of appreciation for the cultural habitats of the UK is a weakness, then maybe it is also one of his strengths as he offers a very different perspective to many conservationists.

He is also bang on the money with his withering assessment of the true economic value (or should that be cost) of sheep farming to the Welsh uplands and deer stalking to the Scottish Highlands. Rewilding has the potential to reinvigorate these areas not just ecologically but also economically.

I think true rewilding e.g. managing huge areas with zero intervention with reintroduced top level predators is very different to managing wild areas in the lowlands, where true rewilding is a non-starter. There are too many mouths to feed, not enough space and far too many zoophobic people. However in these areas we can still have areas of low-intensity land use delivering the ecosystem services that Roderick Leslie describes. It shouldn’t be seen as a choice between one or the other.