Alex Lees is a lecturer in biodiversity at Manchester Metropolitan University and lives in the Peak District. Twitter: @Alexander_Lees

Towards a wilder future – an end to Peak pessimism?

Story 1. Nearly three decades ago I visited mid Wales on a family holiday. It was a successful quest for Ravens, Peregrines, Red Kites and a break from the monotonous topography around my parent’s home in south Lincolnshire.

Story 2. A quarter of a century ago on the, same glorious spring day, I watched Black Grouse at a lek in the Peak District and saw 5 displaying Goshawks sky-dancing at once.

Story 3. Ten years ago I found myself back in mid Wales doing bird surveys, time away from the UK had changed my perceptions of landscapes and ‘wild places’. The landscape reminded me of what I had seen following deforestation in Brazil – rolling grassy hills full of livestock, broken only by introduced tree plantations, and, here and there, tiny fragmented patches of a once great rainforest.

Story 4. Also a decade ago, Red Kites, Ravens and Peregrines recolonised my former Lincolnshire doorstep. The landscape remains largely unchanged; this was a major conservation success story.

After years in the Amazon basin, the most biodiverse place on earth, I now find myself living in the Peak District. The Black Grouse are extinct and a sky full of Goshawks is now a distant memory. In our first full summer in the Peaks we failed to see Wood Warbler; none returned to the Goyt Valley. Pied Flycatchers were almost equally scarce. We did see Merlins and Short-eared Owls on balmy summer evenings to the sound of distant Curlew and Golden Plover. But these were all few and far between across barren expanses of heather moorland farmed for Red Grouse. Hours spent in vigils for a few birds. Wood Warblers need not apply.

I live in the Longdendale valley, raptors are typically conspicuous by their absence and the hills above are even barer than those in the Goyt. To paraphrase George Monbiot, who has been instrumental in asking these questions – and proposing solutions – how did we end up in this mess?

According to The Environment Act 1995 the two statutory purposes for national parks in England and Wales is to:

- Conserve and enhance the natural beauty, wildlife and cultural heritage

- Promote opportunities for the understanding and enjoyment of the special qualities of national parks by the public

If they meet these goals then they should also:

- Seek to foster the economic and social well-being of local communities within the national parks

‘Natural beauty’ is a rather subjective idea, one assumes that human infrastructure like roads, pylons and wind farms disrupting the aesthetics of a natural system is bad, but are happy to accept trade-offs if it means we can cross the country in half an hour rather than five and get greener electricity. But, what about human beings disrupting natural processes and hence natural beauty? Across the whole of upland Britain we kill ecological succession through land management – predominantly burning and overgrazing. A landscape that would be at least partially covered in temperate rainforest, such as Atlantic oakwoods and Caledonian Pineforest with its lush understorey of mosses, ferns and some shrubs is permanently barred from ascendance. That is our terrestrial climax biodiversity home to our real ‘wildlife’ and we are neither conserving nor enhancing it. We are actively persecuting it.

I have personally devoted most of my adult life to understanding the consequences of human change on ecosystems in the tropics. These are landscapes that have entirely changed in decades, knowledge of those forests has not yet slipped from the memory of the people that live there. Yet in the UK we have accepted and even rubber stamped into law with terms like ‘cultural heritage’ what we believe our nominally wild places should look like and the biodiversity that merit the term ‘interest features’. If the Brazilian government celebrated a field of cows, which was once tropical rainforest as a national park it would be met with derision, indeed I have been among the deriders. Yet here we have normalised this, the memory of what the landscape once was has faded, semi-annual degradation is sanctioned. Such widespread cultural acceptance has prevailed for decades.

But not anymore.

Spurred on by a growing rewilding movement the environmental hegemony of this vision of the uplands as a homogenous, treeless, low biodiversity ‘un-wilderness’ farmed for sheep and grouse and all at tax payer expense is being challenged. I attended an excellent Derbyshire Wildlife Trust talk by Tim Birch in Glossop last week. He hoped to see Ospreys, Golden Eagles and Hen Harriers in forty years. I challenged him that it was doable in half that time. It took twenty years for Ravens and those other ‘upland species’ to make it back to Lincolnshire though reintroduction and natural recolonization. These generalist predators can get by almost anywhere that has prey and somewhere to nest, they aren’t picky. I have seen Golden Eagles hunting on the edge of Los Angeles and breeding in a landscape that looked like Lincolnshire in southern Sweden. Even Pine Martens may be quicker back than you think. All we need to do is stop persecution. That part is in theory easier.

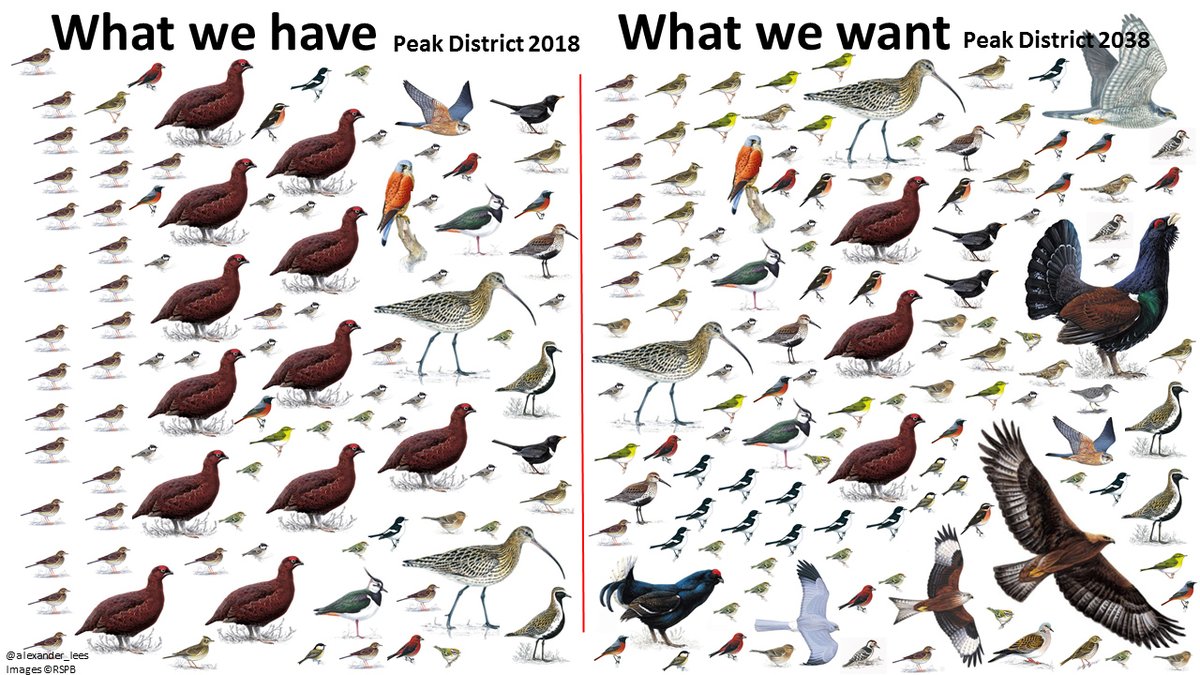

But, for me the focus on raptors, including Hen Harriers, belies the bigger question – what else do we want? Inspired by the talk I put together a figure for my conservation biology lectures at university. Where do we want to go in an age of rewilding hopes? I want to see more of those threatened forest-associated summer migrants, as well as raptors. The silent cloughs should cascade with Wood Warblers. Wrynecks used to nest in the upper Derwent Valley, where the last pair of Golden Eagles also nested in the region in 1668. Why can’t we have Temminck’s Stints on the edge of tree-lined bogs echoing to the sound of Black Grouse and other breeding waders? Are Capercaillies, which stalked these hills only a few centuries ago a pipe dream? Their remains have been found in Fox Hole Cave in the White Peak alongside Golden Eagle and Black Grouse. Bones of a Little or Baillon’s Crake, hint at great wetlands. We need to embrace the term ‘temperate rainforest’ and make plans to redress historical deforestation with heterogeneous habitat restoration across upland Britain.

The ‘manifesto for avian rewilding’ infographic (above) has been visualised over 140,000 times and counting. It evidently resonates with people. Most have been supportive. Those that disagree seem to converge on two arguments – these can be classified into the ‘what about the waders’ and the ‘what about the local people’ problems. These are valid concerns, but I believe unfounded.

Firstly, the current scenario – a vast expanse of very low quality moorland because of burning, draining and grazing provides habitat for low densities of waders because predators are legally (and illegally) controlled. These species are declining because of habitat loss there and in the lowlands, and likely resurgent meso-predator populations aren’t helping. This argument – that we have to maintain the moors as they are, falls down looking at the work the Moors for the Future and partners have done at RSPB Dove Stone in restoring blanket bogs. There wader numbers have increased dramatically in a very short time.

We can drastically improve wader fortunes by restoration. Are we not duty bound to restore native habitat for woodland species? Are they not equally deserving of a place in the landscape? Not all of it, just some of it, a naturally heterogeneous landscape with wader-filled mires on the tops and expansive woods on the slopes and the valleys where space permits. Framing the debate as all or nothing, waders or Wood Warblers is a distraction that is hijacking the debate. We can have lots of both if we make sure that we create lots of good quality habitat in large blocks. Anyone that doesn’t believe that should visit the rest of Northern Europe where bogs are surrounded by forest and natural processes predominate. With healthy Goshawk populations you don’t see the number of corvids (and other meso-predators) and Woodpigeons you see in lowland Britain. We need to consider such trophic cascades.

The future of the uplands and its conservation conflicts involves many stakeholders. The ‘what about the livelihoods’ argument is also not just about the landowners themselves, and their futures but also the local people whose houses may be flooded downslope because the moors no longer hold water. Not to mention their restricted opportunities for connection with nature in a hollow landscape. The current environment secretary has made it clear that subsidies for ecosystem disservices – which aggravate biodiversity loss, flooding risk and carbon emissions have to stop. I would be happy if my taxes went towards paying landowners for ecosystem services and processes like carbon sequestration, biodiversity provision and flood risk avoidance. My wife and I are one of many homeowners in the shadow of the moors, we hope to be able to one day see Golden Eagles from the garden and hear Wood Warblers from the patio. An impossible dream? Don’t be afraid to dream a little bigger.

[registration_form]

This is superb, Alex. Thank you for such a well-argued and inspiring read.

”A landscape that would be at least partially covered in temperate rainforest, such as Atlantic oakwoods and Caledonian Pineforest with its lush understorey of mosses, ferns and some shrubs is permanently barred from ascendance.”

An outstanding sentence in an outstanding article on rewilding. Thank you Alex.

Peak optimism will also be accelerated by the ascendance of land reform too.

Any manifesto to rewild will only really take off if new build affordable homes are seen to be placed equal to new ‘Los Angeles-type’ eagle homes.

Personally I can’t see how any major conservation objective can now be achieved without some form of new nucleus that can co-ordinate and mobilise the conservation community into tackling the big national issues; intensive lowland agriculture, driven-grouse shooting/upland management and malignant development into protected areas. The entire conservation effort is fragmented, dominated by z list celebrity, negativity and genuine effort is spread too thinly and widely. In many cases groups on the front line are un-supported and isolated while the big NGOs are obsessed with retro self preservation rather than connectivity and the evolution of the conservation movement. Without a spear head body that puts pressure on the NGOs to embark on higher risk strategies that connect with the popular movements and pull together as much as the effort as possible in order to mobilise mass co-ordinated action how can any major objectives be achieved? In an age of mass communication, information and democratisation a new coordinating nucleus needs to appear. Without new governing structures there can be no new realities. Big dreams need big action to be fulfilled.

I too have reached similar conclusions and yes, banging the Wood Warbler and other passerines drum a bit more, is a very good idea. There are very localised populations of many birds (eg Pied Flycatcher/ Wood warbler/Lesser Spotted Woodpacker) in Derbyshire, but their ancient Oak and Oak/Beech forest traditional habitat is now rare and localised also. There are also many areas of woodland in the Peak District which seem to have an absent understorey which I am sure is due to overgrazing, either by Red Deer or Sheep. There have been extensive nestbox schemes in some areas, however these surely can’t be a long term solution?

The situation remains, that it is possible to root out key species within the Peak District, however populations really are on the brink for some species. They are a plague away from local extinctions and recolonisation would depend very much on populations elsewhere doing very well. So the overall situation is actually quite dire, I think.

Does anyone have cause for optimism if things are allowed to continue as they are?

I am sorry to say that until there is a change of Government or there is a radical change of thought and approach by them to bringing back biodiversity to our moorlands, (a snowball has more chance of surviving in the fires of hell than this happening), I am not optimistic in respect of our moorlands in England.

This Government and its supporters have so many vested interests and privileges associated with grouse shooting that they are most unlikely to surrender them one inch. The Government has also reduced Natural England (NE) to a puppet organisation which dances entirely to their tune, so much so NE are virtually no longer relevant to protecting nature. It is a very, very shameful story all round.

However I do feel one can be a little more optimistic in respect of Scotland where the Government there I think are at least listening (we hope).

This out now;

https://www.civilservicejobs.service.gov.uk/csr/jobs.cgi?jcode=1574091%20

Northern Upland Conservation Advisers

Natural England

£20500

As an Adviser you will be supporting our Area Teams to deliver our ambitions in the uplands through our Conservation Strategy. Our Advisers work within the Area Team to provide support internally and to work with partners, stakeholders and land …”

No-one works in conservation for the money, but the level of authority implied by a £20k salary doesn’t suggest that NE wants anyone willing to go up against vested interests or who will have the credibility and experience to negotiate effectively with wealthy landowners.

I know what it feels like to be the least well-paid person in the room, and at some level, when they all know you’re not “worth” very much at all, it does affect how they see you. It shouldn’t be like this, but often it is.

NE is guilty of willful blindness in the uplands, and that’s a corporate choice from the top, not the fault of anyone working on the ground. We want the boat to be rocked, NE’s senior management seem to only want a quiet life. Sadly I think that NE is part of the problem, not part of the solution, and has been so for some time.

A good boss backs up their troops. I am reminded of someone like Kochinsky at Leeds University selling the work of their PhD students to huge halls of people. Being the poorest paid in the room in no way guarantees you are the least valued. If you are in a room with a load of people who who don’t value what you do, with no support, then you are set up to fail.

Another stunning guest blog, thanks Alex! Would love to see the MA etc reply to this!

Great article and one after my own heart.

However I’m not so optimistic. While we have large and powerful land owners calling the shots not just on their land but also it seems in the halls of power and a lack of effective policing the persecution of our wildlife will continue and not only our uplands but all our landscapes. it will not change.

I live in the south east, my local woods are festooned with fen traps and snares, shooting towers exist on every corner with game bird feeders everywhere. Hunts chase foxes and hares and apart from the few who oppose them little is being done to redress this imbalance.

Big changes need to be made both in Government and ownership of the land.

I dream of seeing Hen Harriers, Golden Eagles, Pine Marten and maybe Lynx and larger predators return but I fear this will never be acceptable to those who make money from killing things for fun and who currently own and managed these large swathes of land.

What a fantastic read that was! Thank you Alex.

Alex, done the key thing here – working back from where we want to be, rather trying to tweak the disastrous situation we’ve inherited. There’s a big message there for conservation as a whole. Yes, there is a lot to complain about, but there’s a limit to how far that will take you – a compelling, forward looking story is far more powerful. Don’t, as conservation criticism too often does, assume that the people apparently in power know what they should/could be doing – if they were all so all knowing and brilliant why do we spend most of our time going on about how awful they are ? They need our help to see the future. But, of course, people will say, you’ve got to pay for it. Which isn’t the problem it seems: across the uplands many farms seem to be receiving more public money than they make in income. That is a pretty strange state of affairs however you look at it. Doing less could save public money and make farmers richer. That is even before you take account of the big economic benefits: carbon saving and water management. Upland communities do have a hard time and I think they need help and support – but what that does categorically not mean is a right to go on doing things the way they want to – whether it’s high sheep densities or grouse shooting and its associated collateral damage. The time is ripe for big ideas: behind the rigid façade everyone in the uplands is worried sick about the fallout from Brexit – they are going to need the support of a wider community than the miniscule numbers of people who work the land in the uplands, and nature conservationists are an important lobby whose support they need to win.

An excellent read and a dream that many of us living in this area would like to see as part of a reality. I see the work at Dovestones and on parts of Black Hill, Bleaklow and Kinder by groups such as Moors for the Future and Eastern Moors with the RSPB and this does hearten me to some extent. Seeing the return of the blanket bog, mosses, the native tree replanting…areas of bare peat starting to come back to life and hopefully an increase in diversity of species. I’ve seen data from dovestones re increases in wader numbers and would love to hear more about surveys and species populations from the other areas. Science and data to compare with the surrounding moorland would really be useful and potentially give ammunition against the oft quoted benefits to waders from the intensively managed land.

What troubles me is that this is still fairly small scale given the rest of the area and that the good work being done here potentially is undone by the vast tracts of land that is not being managed as well, especially with species that travel over wide areas. You’ve only got to look at the ongoing monitoring work being down by H.I.T at the nearby Moscar estate to see the ongoing use of snares, traps and continued persecution of native wildlife, even where it borders onto nature reserves. Without the major landowners moving on, i don’t see things getting any better. Mark’s blogs and the work that the Raptor Persecution does highlights the power struggles within the Peak district, with the authority and groups such as the National Trust continuing to be silent on some of these issues.

I hope that the ongoing work, the social media campaigns and the challenges people Peak District back to anywhere near its potential.

Excellent article, time for the National Parks to be owned by the state and all the private owners thrown off.

Murray: See http://www.publicfinance.co.uk/news/2018/02/more-planning-approved-homes-not-being-built-says-lga

There are already 423,544 unbuilt homes in England and Wales for which planning permission has already been given.

Perhaps, you should address why they haven’t been built?

Lovely article- thank you, Alex. As Roderick Leslie says, now is exactly the time to be inspiring people about what could be – and getting people to think about different ways of managing the uplands post Brexit. The economics of upland sheep farming is insane – almost every sheep on the hill loses money and they are only there because of massive public subsidy, some by way of Single Farm Payment and some by way of agri-environment schemes. When its all UK Treasury money, surely this cannot go on?

See https://www.rspb.org.uk/globalassets/downloads/documents/reserves/farming-at-haweswater—an-economic-report-2013-2016.pdf

Oliver, that would mean nationalising my house, and all the allotments in the back field.

Very well written Alex, I saw Charlie Burrell from Knepp speak a couple of years ago, and would have liked to have heard Tim’s take on things, however after a long day I did not fancy driving over the Snake. Maybe he will appear at another venue before too long.

The National Trust can go a long way towards this vision, even on their sporting properties, starting with the Snake, and showing adjoining tenants what will be expected of them.

That’s if they are true to their word,and are prepared to take a financial hit in the short term.

Meanwhile, Michael Gove was on the telly this dinner time, stating that agricultural subsidies based on acreage, will be replaced by payments for environmental and conservation based services .

That should have the owners of the 22,000 acres of moorland, currently unmanaged for Grouse, within the Peak queuing up, shouldn’t it?.

Alex, it may be that your glass is half full, and mine is half empty but…. Wood Warblers were relatively common just 20 years ago as far south as Belper, whatever the reason for decline, it isn’t through lack of suitable habitat. Wryneck, extinct in England for decades will suddenly return to the Peak District? really? Birds of the edge such as Whinchat and Ring Ouzel will buck the current national decline by planting their bracken beds and rough pasture with saplings? As for Golden Eagle and Capercallie all I can say is that you have missed out Red Necked Phalarope, we may as well add them to the list as well. With the exception of the Eagle, Capercallie and Wryneck, most of what you list as aspirations were already present in the Peak District 20 years ago and have since declined and are continuing to do so. But nothing is impossible, a quick search on google tells me that the population of Sweden is 9 million and the population of the UK is 66 million so if you can get the population of the UK down to about 15 million I think that you might have a chance. It is also worth mentioning that there is a lot of very badly managed and unmanaged moorland in the Peak District that does not have any shooting interests, maybe we should get those right first?

Hi Derbyshire Botanist,

You seem to be ignoring my idea of a heterogeneous landscape. We want diversity where there is now homogeneity.

First, why isn’t habitat loss an issue? Forest associated species can not persist indefinitely in small patches of forest, they eventually disappear because their populations are too small and fragmented to survive. It is known as extinction debt and is not paid immediately. Wood Warblers are contracting towards the west and towards their core range where they are stable in places. It is likely that habitat loss in Africa is also exacerbating the problem, but questions of habitat amount and habitat quality and trophic cascades in the UK may be driving this pattern and these vary regionally – this from Mallord et al. 2012:

It is currently on the UK Red List of birds of conservation concern (Eaton at al. 2009), the species having declined by 63% between 1995 and 2010 (Baillie et al. 2010), although this masks some regional variation. Repeat surveys of woodland birds in 2003/04 (Amar et al. 2006) showed that the largest declines since the mid-1980s were in south-east and south-west England (–76% and –67%, respectively), with lesser reductions in Scotland (–44%) and Wales (–31%).

Second – bracken birds – is this really the best habitat for them, or is it the only habitat they have left? Yes they won’t occur in woodland/forest but Ring Ouzels are an ecotonal bird in the rest of their range. Whinchats are disappearing from across the Peak and I see no problem with woodland encroachment – they are disappearing as their habitats are being further modified and improved. I saw none last summer…

Why not Golden Eagles? We have Mountain Hares, we have cliffs (and could have large trees) what else do we need? The phalarope is a bit too far south of its climatic optimum but we did have Capers. They have been reintroduced elsewhere in Europe. Once we have forest in the valleys why not?

The fact that all these species are declining within the park is the problem, we are expecting them to survive in a landscape that is not managed with its stated goals in mind.

Population has nothing to do with it! Few people live up there, that is the point – we have an an opportunity to build more resilient upland landscape that actually delivers biodiversity and ecosystem services…

Absolutely not just picking on shooting interests, first port of call should be land managed by NT, United Utilities, FC etc.

best

Alex

Alexander – minor point (doesn’t change your argument at all) – there is a more up to date (2015) Birds of Conservation Concern and red list https://www.bto.org/science/monitoring/psob

Hi Mark, yep was quoting from John Mallord’s paper, thanks.

I think pressures on wildlife in the Peak District do come from people rockclimbing and walking or walking dogs. For example, on a summers day at Burbage, Ring Ouzel never stop their alarm chattering as people encroach on their nest sites. Walking dogs through woods unleashed, or allowing dogs to stray off paths must affect creatures such as Wood Warbler. People simply ignore the ground nesting bird signs. There should be more effort to keep people away from some areas. You can hardly expect Golden Eagles to re-colonise the gritstone edges with people climbing all over them or Wood warblers to select nest sites where a dog sniffs it’s way round it every half hour, or more frequently.

Also last summer I watched on a number of occasions as dogs roamed freely over sites where Winchats were nesting with the birds alarm calling. I think people just generally are unaware of the effects of their own actions.

However with more varied landscape these pressures on some birds may be relieved.

Hi Gerald, absolutely good points, managing disturbance in these landscapes is also super important – at least with the climbers and ouzels there has been some progress. Dogs are certainly a big issue for ouzels and many other species.

best

Alex,

Wood Warblers were stable throughout Derbyshire until the 1990s. The headquarters of this species was always the Limestone Dales, which dwarfed the population of the Dark Peak. Whatever the reason for the decline it lies outside Derbyshire.

Whinchats until the late 80s nested in lowland Derbyshire and in rough areas around quarries in the White Peak until the 90s. Whatever the reason for the decline it lies outside Derbyshire.

Golden Eagles starved to death in the Lake District, or at least their young did. That Golden Eagles could return to Derbyshire in our lifetime is fanciful.

Population is relevant if you are going to reintroduce the big predators, which you would surely need to do.

And finally, its not just about birds……..

Bearberry, fenced off in its southern most outpost in the UK, slowly scrubbing over, surrounded by saplings. An iconic plant from a previous era. A quiet local extinction just as sad as that of the Hen Harrier.

The beautiful Chickweed Wintergreen, growing in a Bracken bed at its southern most site in the UK, saplings have already been planted 500 metres away and we will see what happens next at this site, but I wont hold my breath.

Re-wilding is a huge risk and if done badly would be detrimental on a landscape scale, and from what I have seen of current management in the south of the Park there is little reason to be optimistic.

What are the specifics of the problems in the South Peak District that you are concerned about?

Well Gerard. Off the top of my head, Ringinglow Bog, Hathersage Moor, Houndkirk Moor, Totley Moss, Big Moor, Ramsley Moor, Clodhall Moor and Leash Fen are all under the management of one of the conservation organisations and there are no shooting interests on any of them.

There are also no ground nesting raptors on any of them.

So before we try and enforce a change in management practice on moors that are outside the control of wildlife NGOs, should nt they try and work out why the moorlands that they do control have no raptors. And if they cant work out why, surely the status quo is better.

Derbyshire botanist – we do understand why there aren’t many raptors on NGO land – it’s because there aren’t many raptors anywhere. They aren’t plants – they aren’t rooted. This is particularly clear for HH.

And then there is the flowers. According to the Flora of Derbyshire there are 1900 flowering plants in the county.

In the latest issue of BSBI News there is an article on rare plant declines and extinctions. The commonest reason for rare plant decline is a change in management practice. Either over grazing, or, much more commonly under grazing.

I don’t know how many of those 1900 plant species are found in the Peak District, but lets say its half, approx. 950. Can we be sure that some of those 950 species will not enter a decline through change?

The Bearberry that I mentioned yesterday has been fenced and planted with saplings. In 50 years it will be a wood and the Bearberry will drift slowly to extinction. A trip to the Upper Derwent Valley shows hillsides cloaked in saplings all recently planted, but were those hillsides surveyed before planting?

This is a polarised debate about one species, albeit a very lovely one, the Hen Harrier. However the change that could ensue will affect thousands of species.

A birder looks at a Bracken bed and sees a species poor habitat but below the surface could be something really interesting. If the Hen Harrier returns successfully to the Peak (and I hope it does), but 10 species of grass, or lichen or moss become extinct as a result, will it have been worth it?

Mark – but can you explain why, when a Hen Harrier attempts to breed in the Peak District it does not choose a moorland managed the wildlife NGOs?

And there was a very healthy population of ground nesting raptors up until the late 90s on the moors mentioned previously.

Derbyshire – I can have a go, but unlike the sound of you, I’m not a local so I don’t have local knowledge.

Let me have a go at your second question first. There were healthier, ie bigger, populations of HH in many parts of the UK at that time. A good example of that would be the analysis done of HH movements, productivity and survival on and off grouse moors done at around that time by RSPB using data from raptor study groups. That study would be rather difficult now as the HH are practically absent from grouse moors. And as I explain in Chapter 1 of Inglorious (you have to think about mashed potato and soup) if persecution is high enough on grouse moors it drags down the population away from grouse moors too. Grouse moors are sinks.

A better comparison (because of scale) is between Wales and NI which have very little by way of grouse moors and England which has lots of grosue moors (Scotland has large areas of each and fits the pattern too) – in areas dominated by grouse moor HH decline (even on non-grouse moors) and on areas with little grouse moor coverage, HH increase (over the medium term).

And that’s why (I’m still on your second question) the RSPB Geltsdale nature reserve isn’t lifting with HH – they nest sometimes but don’t do very well because birds are killed locally (see Inglorious again for examples). Birds move around: HH move around a lot. Therefore their fate is determned by the landscape not the patch of ground where they hatched (they aren’t plants).

Your first point – you may know lots more but the cases of HH nesting in the Peak District that I recall aren’t very numerous. There was the pair above the Derwent Valley in 2014 and a pair or two in roughly the same area in 2006 (the males ‘disappeared’) and the pair in the Goyt Valley in 1997 which were guarded round the clock, a pair there which failed in 1998 (under somewhat suspicious circumstances i am told and another unsuccessful pair there in 2003. Are there lots of others? the success rate on grouse moors was awful except in those cases where 24hr guarding took place and/or the broods were fed because the males had ‘disappaered’ – isn’t that right? Hardly a ringing endorsement of grouse moor management, I’d say. So you’d have to tell me what are the relative land areas managed by grouse moors and NGOs over that period for me, or anyone else, to know whether grouse moors are favoured or not. According to the Birds of Derbyshire the successful 1997 Goyt pair was the first successful HH nest in Derbyshire since 1870.

About the plants and correct me if I am wrong, but In areas of succession between heath and whatever the climax forest for the type of ground, there seems to be much greater diversity of plants. So for example where there is Birch scrub, there is often a visibly diverse set of plants in the understorey (grasses, bilberry, lichens, mosses etc) and also the heather (with it’s associated species) and grasses coexisting in patches. This is hardly the situation on heavily burned moors, or is it? About surveying, perhaps it should be compulsory to survey for rare plants, I could go along with that and finding conditions to support endangered populations of plants. The same applies to other things too. Also there is nowt wrong with Bracken, for example if you walk up or down Barbrook there is plenty but it is actually quite localised in the Eastern Moors area. I know of quite big patches especially further south. I walked up Cukcoostone Dale last summer with the kids and it was towering above me in places, also patches in Shining Cliff Wood. Are there limits on what kind of ground Bracken will cover?

Also if you want to attack the Eastern Moors Partnership, I think talking about Merlins would be more productive since I think they bred in the region until very recently.

Is Big Moor overgrazed?

What is it about these places (Ringinglow Bog, Hathersage Moor, Houndkirk Moor, Totley Moss, Big Moor, Ramsley Moor, Clodhall Moor and Leash Fen) that is annoying you? I Know Leash Fen and Big Moor fairly well, but what are the specifics?

Just returning to this article. Sad to see such a regressive and short sighted view of landscape scale restoration from you, Derbyshire botanist. Judging by your questions, which seem often in bad faith, you need to seriously educate yourself on what a population sink is. The idea that re-wilding is ‘dangerous’, but the current status quo of massive wildlife declines isn’t, suggests you are clinging on to ‘traditional management’ at the expense of everything else. Now, who else has that mindset?

It’s quite an irony that Lincolnshire now holds more Peregrines, Red Kites, Buzzards and Ravens than the Peak District National Park. The popular vision is that we are a flat desolate landscape whereas the Peak is one of Britain’s lungs, a natural gem. There is still large scale pheasant shooting in Lincs and there is a degree of raptor persecution but it pales in to insignificance, a bit of shop lifting, compared to the industrial

scale organised crime perpetrated in our so called National Park. The organised crime is a nexus of oligarchs who control the land and their thuggish minions who enable their pleasures. But it’s worse than that, the nexus includes the state and NGO bodies set up to protect our environment. All are subject to regulatory capture. Overturning this behemoth to build Alex’s vision would need a mass movement of people electing politicians who will implement their will. Not supine types who pander to the elite vested interests. Are their any politicians that share Alex’s Vision? I’d like to hear from them.

Derbyshire Botanist, i fully agree.

Phil Espin, I have no information on Raptor numbers in Lincolnshire, but please do not confuse the

“Dark Peak”, with the National park as a whole, where good populations of various Raptors exist,

alongside shooting interests.

However, I will concede to you on Red Kite, for now.

Hi Trapit, info on persecution in the Dark Peak widely reported – e.g. http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-derbyshire-42210335 it wasn’t always the case as my Goshawk tale attests. best Alex

Alexander, sorry for any confusion, I was comparing the poor situation in the Dark Peak, with area’s

In the southern half of the national park that offer a more benign habitat for Raptors.

Trapit. I’m sure your point about raptor numbers in different parts of the park could be a fair one. I’ve done a bit of googling and can find no data on the raptor populations of the different UK national parks. Such data would be a valuable part of establishing the biodiversity deficit of our uplands. Alex Lees is there a quantifiable measure of biodiversity deficit that can be used to show just how degraded particular landscapes are? A league table of UK national parks in terms of biodiversity might make the park authorities take a bit more notice, if they are in the relegation zone!

Hi Phil, that is a fantastic idea and ought to be readily extractable from BTO data already in existence.

best

Alex

Good lad and well said just about sums up my opinion on your post Alex, and I for one after 42 years of writing wildlife and environmental columns, in both nationals and locals, 28 years based at Bleak House, Crowden, still hope that, all or part of your dream will become a reality. I especially liked the reference to Black Grouse, as 35 years ago I watched a single bird on top of the Snake, and I’d like to mention a sadness or two of my own, the long gone nightjar that could be heard from my hilltop eyrie at Crowden in 1980, the dunlin and the occasional dotterel pottering about the air shafts of the Woodhead Tunnel. Having said all that, and I will never ever knock your optimism, I am still writing about the exploits of the same moronic and ill informed so-called ‘Country People’ that I have been castigating for four decades. Unfortunately, much of what you say about the countryside and the Government et al, lack of action, lack of understanding, lack of common sense, is still linked intrinsically to the aforementioned morons. One feeds the other outdated platitudes and to be frank, absolute shite, and vice versa, and it is people like you, Mark, and indeed myself who try and pick up the pieces. Just think what you could do if you owned the same amount of land as the Duke of Westminster. Mark may remember some of my work for the RSPB, from the days of Derek Niemann, Chris Harbard and the more recent incumbents, and the President recently sent me a nice letter thanking me for the all the coverage I have given the RSPB over the years. Mark knows the score, you know the score, and more power to your elbow, and never give up. Sean Wood FBNA

Sean – many thanks for this.

Hi Sean

I live in Hadfield a few km down the valley and Longdendale really feels like ground zero, the first thing we need is to show what has been lost, not just on decadal time scales but over the centuries, records like your Black Grouse are an important datapoint in that fabric of lost wildlife – do you have any pics of any of these?

best