This will undoubtedly be one of the wildlife books of the year and it is a cracking good read. You should read it.

The book tells the story of the wilding of the Knepp Castle Farm, in Sussex, by its owners Sir Charles Burrell and his wife, the author of this book. So this is an insider account of what happened at Knepp, and why, and how, which adds lots of delightful and juicy colour to the bare bones of the story. But the bare bones are exciting enough – there has been a rapid and massive resurgence of nature in the last 20 years but particularly in the last eight years. Knepp is probably the best place for Purple Emperor butterflies in the UK, may well be the only site (or certainly one of very few sites) where Turtle Doves have increased singificantly against the national downward plunge in numbers and has a lot of Nightingales too.

This natural renaissance has been achieved through restoring grazing by Tamworth pigs, allowing scrub to spread, blocking drains and generally working with natural processes – letting nature take its course. And this is on a big scale – 3,500 acres (1400ha) – bigger than many a perfectly decent nature reserve. The estate has been turned from a struggling farm into a completely different animal – wildlife is the main crop, and the visitors who will pay to come and see that nature are one of the new novel income streams.

The owners of the land deserve a huge amount of credit for their bravery and vision, and their efficiency and determination in seeing that vision through to its current position. It clearly wasn’t easy to gather support for the idea and there must have been moments of doubt along the way.

However, although the story is somewhat framed as being ‘the visionaries against the bureaucracy of the conservation establishment’ it is worth noting that Knepp has received a big pile of taxpayers’ money to produce this wildlife. The author relates (p175) that ‘Natural England’s initial reluctance’ to allow Knepp into the Higher Level Stewardship scheme was ‘the bureaucratic tail wagging the dog’ which is one way of looking at it. But these aren’t trivial sums of money. Although I couldn’t find the amounts mentioned in the book, Knepp Castle Home Farm received £386k in 2016 and £306k in 2017. This was not all HLS payment, some would have gone to any farmer owning the land, however hopeless their environmental record, but the fact remains that over a 10-year payment period the taxpayer is handing over millions of pounds from a limited pot of money. I have no problem with this, but it would be a bit surprising if such monies were handed out without a bit of bureaucracy. And an HLS application wishing to unleash boars, bison and beavers into the Sussex countryside was not a completely normal and straightforward one! The Knepp team were fortunate that the system granted them such riches from the public purse, and we the public are fortunate that they delivered the goods for wildlife. We aren’t going to get more nature for nothing even though it was our money that encouraged quite a lot of its destruction in the past.

When CAP payments end after Brexit (if there is a Brexit), and current agrrements end, we will need to decide how much money to give to the Burrells at Knepp and how much to give to other farmers (like this one) and on what basis. And what will be the conditions attached to our support? And are we buying environmental goods or just renting them for a while? At the outset, the Burrells wanted the option of stopping the wilding process after 25 years so that their children and grandchildren would be free to make their own decisions about the land – understandable but where does that leave the taxpayers’ investment if the next generation opt for intensive farming which trashes the wildlife that we taxpayers have paid to arise?

This book plumps for payment for natural ecosystem services as the basis for a post-CAP payment system. This is a good idea – but how do you measure the delivery of those services? Or should the state, on behalf of the taxpayer, just take any old landowner’s word for the fact that they are going to deliver good value for money? If we are going to pay for flood alleviation, water quality, carbon storage, wildlife and pollination services then who measures them and how do we rank them? And what are they worth?

Do we go for land sparing or land sharing? Knepp is an example of land-sparing – land is taken out of agricultural production (not entirely, but mostly) and instead managed for wildlife, carbon, clean water etc. With our pot of available money do we go for lots of Knepps and let the land in between, the vast majority of the countryside, go hang, or do we have fewer Knepps and spread some of our money thinly elsewhere so that some good is done everywhere alongside food production (land-sharing)? Which would you do? And then how would you persuade HM Treasury not to give the money to the NHS or education instead?

What has been achieved at Knepp is amazing – I’ve never visited (though I’ve been asked) but without exception the people I know who have been there have been blown away by the place and what has been achieved. It stands as a beacon of hope, and what is more, a working example of success, not a pipe-dream. Ironically, if it had fallen flat on its face then it would be easier to live with in some ways – the project’s enormous success raises a whole bunch of issues for the future about how we build its lessons into future environmental policy at the public expense.

I came across some passages which I thought were wrong or unfair, but that doesn’t matter much because taken as a whole it is an extremely enjoyable, stimulating and challenging read. I think it is also Knepp’s bid for its future share of public funding – and I hope they get it too!

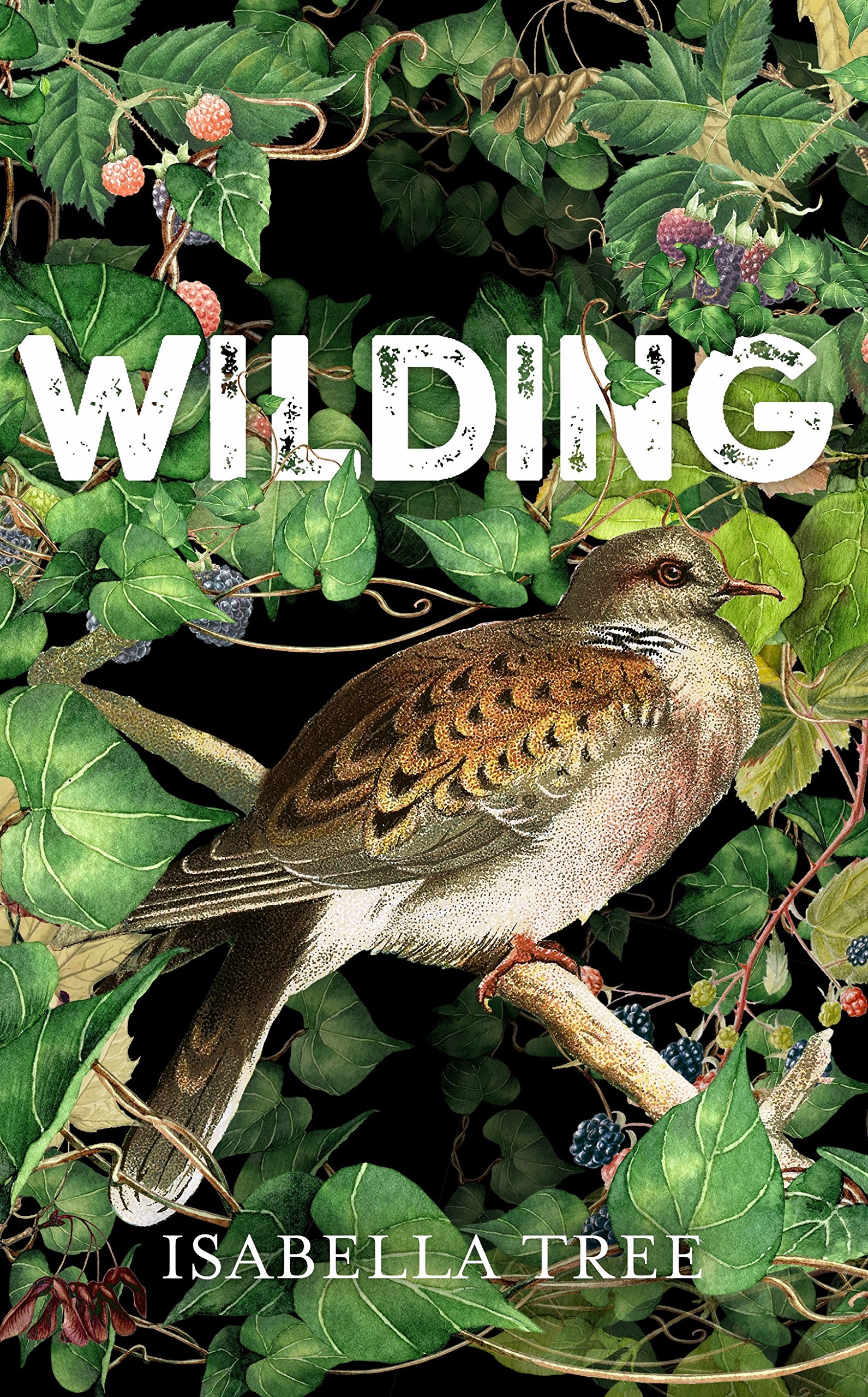

Wilding: the return of nature to an English farm by Isabella Tree is published by Picador.

Remarkable Birds by Mark Avery is published by Thames and Hudson – for reviews see here.

Inglorious: conflict in the uplands by Mark Avery is published by Bloomsbury – for reviews see here.

[registration_form]

Sounds well worth a read. Any mention of White Storks in the book? I hope they are not going to proceed with that proposal as I think it risks giving the place more of a theme park feel than the flagship for rewilding it is now. Storks are regular visitors to England but there is no evidence that they used to be regular breeders. Any project to establish a breeding population would be an introduction rather than a reintroduction. I’d heard the plans involved trying to train the birds into being resident rather than undertaking their expected migration south for the winter, something that would add to the theme park feel. And once storks are installed, what next? Some lovely pink Flamingos perhaps, or what about Bee-eaters? It would save us having to head south to see them.

Releasing storks would be dewildling not rewildling and would risk damaging the well-earned reputations of all involved on both the rewilding and reintroductions side of things. I hope they think twice.

An interesting point is made in this month’s BBC Wildlife article about Knepp. They are apparently concerned that the site may end up qualifying as an SSSI for one of the species it supports – for eg, if there are further declines elsewhere it could become for Turtle Dove what Lodge Hill has become for Nightingale. If it were to be notified as an SSSI then they would be obliged to manage it for that species rather than letting nature take its course. You’d hope NE would be pragmatic about this and hold back but with all that HLS funding who knows.

Ian – no mention of White Storks. The SSSI point is made though. I think the point goes further than just the conservation action – it would be difficult for future owners of Knepp to start groing wheat if they suddenly fancied the idea too if it were an SSSI.

No “boars, bison and beavers” at Knepp yet was what I read, but Tamworth pigs and Longhorn cattle substitute for the first two and beaver remain an aspiration, probably quite realistic now that Mr Gove is such a fan.

This is an inspiring book and very well written. While the odd dig at NE ‘bureaucracy’ and slight sense of entitlement to public funding are minor irritants, the many public benefits and lessons learned deserve our support. The author’s descriptions of the difficulties faced in public perceptions of ‘wilding’, ‘natural processes’ and encounters between walkers, horse riders and free roaming herds of cattle, pigs and Exmoor ponies are perhaps the most interesting challenge – how can we bust the myths of ‘abandonment’ and ‘wilderness’, and address the profound cultural legacy of land ‘improvement’ and ‘shifting baselines’? This book provides some answers, but to learn more and engage wider public support we will need other large scale wilding projects (beyond Knepp and Ennerdale) in England, and especially in Wales where the current ‘Brexit and our Land’ consultation from Welsh Government and the Minister’s priorities for protected landscapes (published 27 July) are opportunities for a robust and well-evidenced debate.

Ennerdale? Regen Sitka everywhere and mass Larch disease. Amazing that they even started cutting down Sycamore but not Beech which itself is regen everywhere!

Considering how much money Knepp has received from the public purse (£415k/year from HLS and BPS according to the latest BBC Wildlife Magazine), I would expect to see a long-term commitment to nature and not just for 25 years. Wanting an option to stop after a certain period of time, highlights the problem of the lack of publicly owned land in the UK, which is there for nature – as in private hands, land use is always at risk of being changed or sold.

Good points re the public purse and the lack of land available.

Surely, a fair and effective way forward is to tax land, thereby slashing land prices and opening up the countryside to regeneration and large scale rewilding.

It’s about time we loosened the Plantagenet’s grip on it’s horizon to horizon ownership.

All of the big arable operations across Wessex, the Brecks etc – the ones that have driven nature from the countryside, have been in receipt of payments of hundreds of thousands – some over a million – each and every year, for decades! The vast majority of NT, RSPB and Wildlife Trusts reserves / farm holdings also receive heaps of farm subsidies. Let’s not pick on Knepp without some context!

Messi – I’m quite happy to criticise the conservation orgs you mentioned too, as I feel that they are over-reliant on agri-env funding, but this book review is about Knepp.

My main gripe is the temporary nature of the whole thing if they were to change the land use after 25 years. In the BBC Wildlife mag, Charlie Burrell advocates more “pop-up” Knepps elsewhere for a similar period of time, with the option of returning to farming if farmers want to do this. For me, this is far too short for a landscape to recover from farming and to mature. Plus, it provides no long-term protection for nature.

‘Over-relient’? A key point here is that public money (e.g. agri-env funding) is supposed to support public benefits that’s aren’t provided for properly by the market. We have to rely of public policy to correct such market failures if they’re to be delivered. Short of bringing huge areas of current marginal farmland into public ownership and allowing to to rewild, it’s hard to see how else one could induce private landowners to deliver things like carbon sequestration, water attenuation, biodiversity recovery……and of course bringing these areas into public ownership would be costly on the public purse up-front. So we’ll have to pay private land owners to deliver if we want more nature etc.

I have no problem with charities also receiving public support for delivering public benefits. I’m an RSPB member and donate to RSPB land purchase campaigns, but I’m not the only one benefitting from what they do – the general public does too, so they should provide some support too, through general taxation.

I agree it would be awful if Knepp returned to intensive farming. All farmland in private ownership receiving funding to do things for the public present the same risk. What do you suggest? Enforcing restrictions would be a great incentive for private land owners to carry on intensive farming. I reckon we need to combine both large-scale public land ownership, to deliver guaranteed permanent habitat creation, with more risky conservation on private land.

I’ve no problem paying private landowners, public money for public benefits. Especially, if the funding gets results, like HLS for farmers generally does. But perhaps this could also be means tested like payments are for people claiming benefits? As even without agri-env payments, the yearly income for Knepp largely from owning land/buildings is pretty substantial – £1.01m (£590k from renting out buildings, £120k from farming meat and £300k from camping/safari/guided walks) which increases to £1.425m with HLS and BPS (according to BW mag), even though a lot of the biodiversity gains were achieved from just letting scrub grow.

My point about being ‘over-reliant’ on agri-env funding was aimed at the conservation orgs you mentioned – RSPB, WTs and NT. Sticking livestock on nature reserves and removing scrub is a valuable and easy income stream for them (eg nearly £1m for Surrey Wildlife Trust’s heathland restoration, which involved tree felling, scrub clearance, turf stripping, controlled burning, grazing of Chobham Common over 10 years via HLS) and I’m not convinced it is always in the public’s or nature’s best interests.

Yes on reflection maybe the book was a bit presumptuous about public subsidy, but I loved Isabella Tree for pointing out that the vast quantities of food wasted across the world made any argument for the need to farm even unproductive land to the death absolute nonsense. Cut food waste then there’s more land, lots of it, for nature. It was brilliant to see in the very latest issue of Nature’s Home that in a list of five things that we can do as individuals to reduce the impact of agriculture on wildlife the second was ‘avoid wasting food’. The topic deserves regular multi page articles in publications across the conservation world, but this is perhaps a long overdue beginning.

Mark may I humbly suggest that for a future book review you have a read of Pete Minting’s ‘Amazing Animals, Brilliant Science’. I’m sure you’ll see why this is noteworthy, and rather unique, book on several levels – and the frequent and entirely objective references to how huntin, fishin, shootin is impacting on wildlife and conservation policy really make you realise that the folks with guns (and sometimes rods) are rarely far away from attempted screwing up of what we are trying to do. The most revealing story is his recollection of being at a Highland fair in 2014 when a major landowner came up and pointed to a big picture of an adder at Pete M’s stall and said proudly ‘We kill hundreds of those every year on our estate!’. I suspect an awful lot of grouse are killed there too.

Here’s the irony about the dependence on funding at Knepp – the delay in receiving agri-environment funding for the Southern Block meant that it scrubbed up in the absence of grazing. Here from “Wilding” pg 118-119:

“But clearly nothing was going to happen soon and without funding we had no means of erecting the £100,000 deer-fence around the Southern Block boundary, plus the £50,000 needed to remove culverts, bridle gates, fences, field gates, river gates and bridges.

We had begun taking the least productive fields of the Southern Block out of conventional farming in 2001, continuing in increments over the following five years. With no immediate prospect of introducing herbivores into this area we decided to avoid the cost of re-seeding with a native grass mix as we had in the Middle and Northern Blocks and simply left the fields as they were after the last harvest of maize, wheat, barley or whatever crop had happened to be growing. By 2006 all 450 hectares (1,100 acres) had been left to their own devices for between one to five years, while we continued to petition the powers-that-be for the wherewithal to put a conservation grazing strategy into action. Ironically, this frustrating hiatus proved the most positive move of all for rewilding. Our haphazard process of freeing the land in stages, combined with no re-seeding of grass and a delay in introducing the heavy-hitting grazers, proved to be rocket fuel to natural processes, generating opportunities for wildlife that were far more exciting than anything we were doing elsewhere”

So, what was the “natural process” that was the driving force for the return of nature at Knepp? Well, it wasn’t from restoring grazing. It was the development of scrub in the absence of grazing. I was able to deduce this before the book came out from satellite imagery over the years and from the 10th anniversary report. Knepp will receive ~£4.2m in CAP payments over the life of the HLS to 2020. Scrub development in the Southern Block was done for free by natural processes. I just don’t understand how such a simple analysis seems beyond commentators on Knepp who seem bound up in the hyperbole.

Things like turtle doves need more than just ‘scrub’, Mark.

The southern lowland landscape would once have had groups of wild boar, herds of aurochs, beavers etc – brutish beasts creating sand and water wallows, knocking through and browsing the shrubs, chomping down trees, creating grazed lawns, heaps of poop. I suppose the owners are just trying to be pragmatic (no aurochs; can’t get permission to stick boar in, yet) and exploring what happens with animals that are somewhat close in nature to aurochs and boars. Yep, like every other farmer across the area, they’re getting subsidies – but they’re also delivering something in return that some people appear to appreciate.

That livestock had nothing to do with the arrival of the turtle doves is confirmed by a study of species changes in bird assemblages on abandoned land in Galicia in NW Spain where traditional agricultural and livestock activities had ceased. During the period 2000-2010, a gradient of change from bare ground and open shrubland to closed shrubland and woodland in the absence of livestock grazing led to a significant increase in 13 shrubland and forest bird species, including species of conservation concern such as turtle dove, Dartford warbler and Western Bonelli’s warbler

Regos, A., Domínguez, J., Gil-Tena, A., Brotons, L., Ninyerola, M., & Pons, X. (2016).Rural abandoned landscapes and bird assemblages: winners and losers in the rewilding of a marginal mountain area (NW Spain). Regional environmental change, 16(1): 199-211

Why is it that when people advance romantic notions about past landscapes, a large carnivore is never part of the scene?

MaArk – that doesn’t actually mean that livestock had nothing to do with what happened at Knepp – your logic is flawed. But it is a valid and interesting point provided you don’t overplay it…

Mark Fisher – regarding large carnivores, I bet Isabella would love to have them. Are you asserting that they can but won’t? Same with wolves? Farmers et al. live in the real world and, unfortunately, our government isn’t yet allowing lynx re-introduction. Given the huge numbers of deer in southern England I’m sure lynx would thrive. Maybe you could explain what you’re doing yourself to get large carnivores back?

You can’t assert that a single study from Galicia ‘confirms’ what’s gone on at Knepp – that’s scientifically illiterate (to borrow a term you frequently throw at others). My contention is that we know that turtle dove territories are strongly associated with proximate fresh water and annual plants, and that large browsers and grazers may help to maintain wet pools and disturbed ground in among the scrub. Scrub is one, but not the only, key predictor of turtle dove settlement.

I thought this was an extraordinary book…and like you have many more questions to ask about the future of the countryside and how we can farm the land and also create permanent space for wildlife.

I live in rural Somerset…land of milk and cider…large dairy units and commercial apple crops. There are pockets of deciduous woodland, but mainly large field systems with no field margins for wildlife. The habitats with the greatest abundance of wildlife that I see are walking down green lanes and droves…narrow lanes with high overgrown native hedges, and also a derelict mill…with safe high nesting places for many birds. But one of my favourite places to walk is an area (I’m guessing about 40 acres) bought by the community and ‘re-wilded’ with native trees, a wildflower meadow and large pond. It’s a place for humans and animals…it’s in a rural area, yet it feels like an oasis of wildlife in the managed countryside…imagine if all counties had many areas like this permanently given over to wildlife…to act as green patchwork and green corridors…for humans and animals.

Hi Mark Fisher. In regards to your point about the ‘natural processes’ that led to the scrub establishing in the absence of grazing…

…As you say the scrub established naturally, as it does on any set aside land. (I don’t think its establishment was ever attributed to the presence of grazing animals).

But I don’t understand how you conclude that this is the reason that nature is returning to Knepp?

Surely the return of nature to Knepp is a result of the herbivores interactions with the vegetation.

In a cyclical system the herbivores can be introduced at any point of the successional cycle and the presence/ behaviour of the cattle, ponies, deer and pigs create myriad effects on the vegetation, and consequently a diverse array of niches.

So surely it is the result of interactions between herbivores and vegetation, that Messi describes above, that is the driving force? Not just the presence of the scrub itself?

Mark Avery – I visited Knepp a few times four years ago, in the presence of a couple of walking encyclopedias, and the diversity of species blew my mind. Whether grazing is the key or not, it is a magical place worthy of the funding and definitely worth a visit… in my opinion.

Precisely, Dan. What Mark (Fisher) appears to lack is an understanding that a) the English lowlands used to have herds of aurochs, lots of rooting boar etc, that b) they were significant ecosystem engineers, that c) the Burrells would likely far rather have had aurochs and wild boar if possible but that d) they had to go for domesticated forms which are far from ideal but that are behaviourally quite similar to these wild forms. And it’s an experiment which is yielding unexpected and useful results, on private land. Isabella also explains why they don’t like to call their work ‘rewilding’. Mark, you kind of have to live and let live sometimes.