Thirty-three years ago, at this time, I was walking around the Flow Country in the north of Scotland in my first few months working for the RSPB. Last year, at this time, I was in the northwest of the USA. What links those two times is the trees I was looking at. In both cases they were Sitka Spruce and Lodgepole Pine. These two trees are native to North America but were the non-native species chosen for large-scale afforestation of the peatlands of Caithness and Sutherland which galloped ahead in the mid-1980s.

My role for the RSPB in 1986 was to lead some research into the impacts of afforestation on the birds of those remote peatland areas (see Fighting for Birds Chapter 2 and also Birds and Forestry for an overview of the issues).

The afforestation of the Flow Country is a fascinating case study and a sad tale of destruction. In fact, like most issues, it’s a mixture of good and bad, of right and wrong and of triumph and disaster. This area straddling the Caithness and Sutherland border just before you get to Thurso, Wick or John O’Groats was neglected by nature conservationists and then pounced on by the forestry company Fountain Forestry who realised that the Flow Country, through a combination of low land prices, planting grants and provisions for tax relief was a great place for rich highly-taxed people to make more money out of forestry even though it didn’t matter much whether the trees grew well or not. It was a very clever move but it led to massive damage to a great place for nature and a wonderful landscape.

I’ll never forget standing and watching a powerful tractor, with caterpillar tracks (preventing it sinking into the bogs) pulling a massive plough which created a black furrow as it turned over peat that had been buried for thousands of years. It was as smooth and as impressive as someone using an icing bag to decorate a cake. The peat was sliced out of the ground and dumped in neat rows, like decoration, and the trees were later planted in the exposed raised rows of upended peat. The trees that were planted were those Sitka Spruce and Lodgepole Pines from North America.

I was back in the Flow Country last week, boring my grown-up offspring with tales of what Dad did when he was their age.

We walked over the short boardwalk across the bogs and through the dubhlochans to the tower that gives you a view over the landscape.

The landscape would look better without the trees but if you keep looking down then you see Sphagnum moss, Common Lizards, Cotton Grass and Sundews.

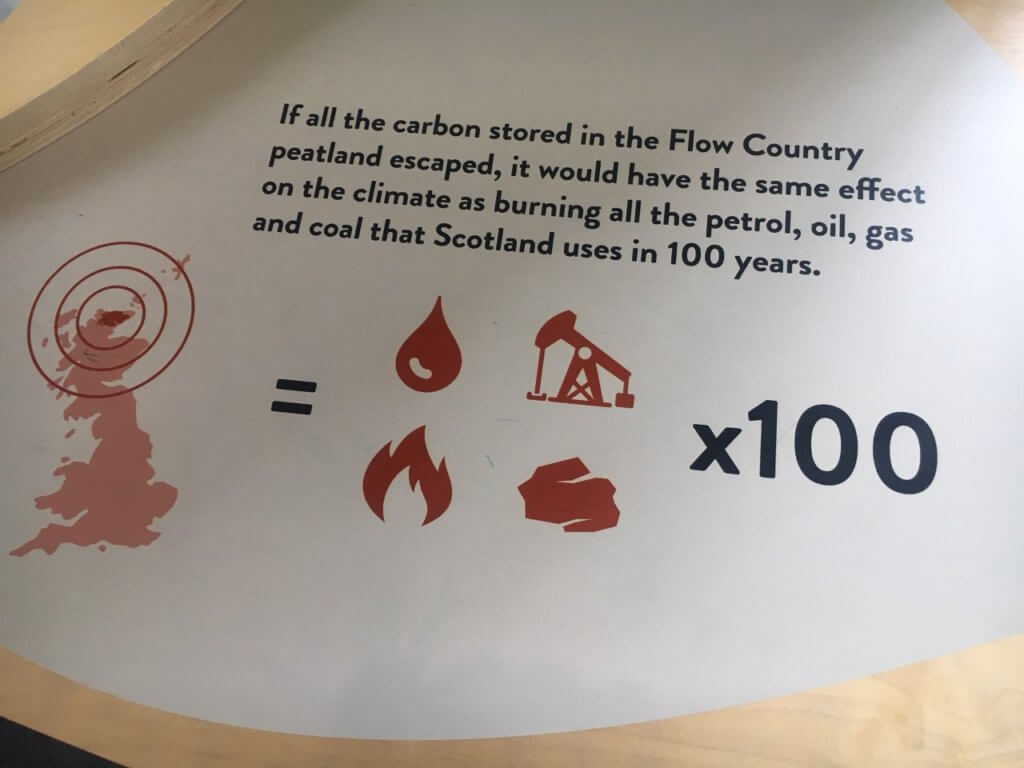

And we visited the RSPB visitor centre at Forsinard, in the railway station building – it’s an impressive display.

A good way to see into the heart of the Flow Country is to get the train from Forsinard station to Thurso, have a late lunch in Thurso, and then head back to Forsinard. That’s what we did and the most challenging bit was finding somewhere in Thurso that does lunch (or anything else that looks like food) at 230pm (I recommend YNot – because it’s open!). I also recommend the pair of Arctic Terns nesting on the far side of the track at Thurso railway station.

The journey through the Flows by train is an eye-opener. The trees have grown in the past 33 years – some of them well but others not so well. The RSPB has been clearing trees in some places with EU funding – people were paid to put them there and then they were paid to take them away. But it’s a damaged landscape without a doubt. I’ll go back one day and have a closer look at the wildlife but even if every single Dunlin, Golden Plover, Greenshank, Common Scoter, Red-throated Diver and Black-throated Diver is still there, it’s still a damaged landscape.

I felt a bit low about it, but it was an interesting day. But nature was kind enough to provide a pick-me-up on the journey back to where we were staying – two White-tailed Eagles and a ringtail Hen Harrier as we drove, to add to the two Golden Eagles and a Short-eared Owl we had seen from the train.

I have a more uplifting story to tell of work elsewhere in the region later this week.

Mark,

This might be before your time at the RSPB but when Fountain Forestry was just getting going and a certain famous BBC Radio Breakfast Time personality was being flown in by helicopter to review his investments, I tried to get the RSPB (Highland office) interested in what was happening in Caithness with a distinct lack of success. It might have been my lack of persuasive skills but I got the impression that anything that might upset the wealthy potential benefactors of the RSPB was not a high priority. The experience soured me on the RSPB for a very long time indeed.

Do you have any insights you might care to share about the organisation when you first started.

Stuart – well that’s interesting. I started in 1986 and it was specifically to work on this issue so the RSPB was very engaged with it then. I was just a junior scientist but there were lots of heavy-weight policy people spending loads of time on it then. How the RSPB got from the situation you describe to the one I encountered I don’t know.

I think the importance of the Flow Country ornithologically had been overlooked by everyone. There was quite a lot of catching up to be done by NCC and by RSPB and the pace of change was very quick.

I very much doubt that any lack of engagement was due to a fear of upsetting wealthy benefactors though – the RSPB model has always been to rely on a mass membership. A million voices, and financial contributons, for nature is a very different model from a few hundred very wealthy benefactors which is more the situation in US NGOs and, for example, the GWCT and Moorland Association.

Thanks for your comment. Maybe someone else out there could add the details I lack…

What the mythology of the Flow Country has done its best to iron out – and which could well become increasingly relevant today – is that a key cause of the Flow Country was the Scottish Office agriculture department’s refusal to release sheep farming land which was clearly unviable to everyone but them – a disastrous example of the agricultural religion we’ve swallowed, and in many cases continue to swallow, for 70 years. Well before the Flow Country – and today equally – we should have been planting trees further down the hill. This I think is what conservation should be advocating now – even more so around towns and cities – because simple opposition could well bring on a repeat performance as all eyes focus on carbon and nothing else.

The heart of the Flow is about as inhospitable to sheep as it is possible to imagine. I think most sheep put out to graze would starve or drown. There is a lot of quite decent grazing along the river edges which is also a pity the Helmsdale river has a lot of pretty much knackered native woodland and it would be stunningly beautiful if that could be restored.

You are however right in that it was land policy which kept the system as it was and probably did not give a lot of opportunity for landowners to make money out of their holdings – perhaps forestry in more sheltered areas (grazed by sheep) where the trees would actually have a chance to grow would have saved the more desolate area where all the waders and scoters are.

Mark,

Coincidentally, I was at Forsinard last week too (on Tuesday). The sign that interested me out on the bog, by a lone pine stump, was the one that read “Stumps of wood like this are all that’s left of woodland that once grew here. About 4,500 years ago, the climate became drier and warmer, making conditions more suitable for trees to grow. After just a few hundred years, the weather turned wetter and colder again, and the trees gradually died as their roots were swamped by the growing layers of peat [etc]”. It is certainly true that there are abundant pine stumps in peat right across the Highlands, including the Flow Country, and many do date to about 4500 years ago. However, the bit about it all being forced by a short-lived warm period is much less securely based. It is not even clear whether the stumps are the remains of trees that grew because it was drier for a period, or the ones that died because it became wetter (or both). And it is further removed to determine whether any greater dryness or wetness came from climate or ground conditions. Pines on bogs will die without any change of conditions – they get bigger, sink under their own weight, until roots are in permanent water, and that is it. Pines of decreasing size nearer the centre concentrically around a bog are easy to see in Scandinavia, but also locally in Scotland (Rothiemurchus, for example). But the wider picture is more complex that that. Evidence from the Flow Country is that pines were most abundant earlier, perhaps 8-6000 years ago, after which they, and other trees, were gradually replaced by expanding peatlands. The present peaty, treeless nature of the Flow Country is not quite post-glacial in nature – it developed within the last 10,000 years, from a more wooded earlier stage immediately post-glacial. The reasons for the shift may lie partly in the continuously cool and wet climate, leading inexorably to an increase in waterlogging over time, and partly due to loss of remaining trees in the later postglacial (after say 4-3000 years ago) as a consequence of human activity of all types, including introduction of high densities of grazing animals, cutting, burning, etc.

What is reasonably clear is that the Flow Country has had a much more wooded history in the past (evidenced by the Forsinard stump, among millions of others), and would likely be a bit more wooded now, locally in mosaics, without the current degree of human pressure. The bit about the 1980s debates that I remember was the pro-forestry lot citing the stumps as evidence of former woodland (so why not bring some back), while the other side were arguing that the Flow Country was “Europe’s last great wilderness” and similar phrases. I tried pointing out that those stumps, and other evidence, did provide a reason for caution in this argument – something patently has changed over time – and it would be much better to argue from where we are now rather than from where the landscape might be if humans had not existed (an extrapolation fraught with a myriad of uncertainties). I still think that. It would be good to get some more woodland growing, but it should be native species, locally (in valleys, along the rivers, etc), inter-digitating as naturally as possible with the great wide peatland expanses you write about. And absolutely not those exotic conifers dug into ploughed peat that has accumulated for millenia, is storing carbon that we do not want in the atmosphere, and which contains a fossil record that has only partially been extracted.

Next time you are there, head west for lunch to the wonderful Garvault Hotel – remote, friendly, unforgettable …

Keith

Keith – we were there on Wednesday. What a treat it would have been to meet you unexpectedly there.

Thanks for your knowledgeable comment.

Gervault – I know the location but haven’t been through the door for 20+ years.

Cheers Keith, very informative comments as Mark said. It had never occurred to me that as the tree grows bigger and heavier it will sink into a bog and the roots will drown, thanks for that. You are dead right that some of the assumptions about past climate changes and how they affected the land and wildlife are weak and simplistic. I remember attending a two day course in 1990 and telling some other participants at our dining table that it was believed the same shift you mentioned to a wetter climate approx 4,500 years ago that was responsible for us losing the lynx. I had read this in a well respected publication, and it did seem very plausible – how on earth could our ancestors have killed off the elusive, solitary lynx thousands of years before they managed to get rid of the wolf or the difficult to miss bear for that matter? Then of course a very few scraps of lynx bone from a Yorkshire cave were properly dated to 1,500 years ago and showed in hindsight this was somewhat presumptuous rubbish really – the lynx is a mammal not a reptile after all (wish that had occurred to me in 1990). Without the discovery of a few bits of bone to show the lynx survived at least 3,000 years longer than originally thought the political realities of reintroducing it would be even more problematic than they currently are. Too many assumptions are being used to fill in blank gaps in our knowledge of the past and that’s dangerous, the ongoing arguments concerning whether natural European forests were closed canopy or predominantly open are at least testing old assumptions that needed to be. I can’t resist since referring to those lynx bones to mention that a skull of an extinct scimitartooth cat – homotherium – was trawled up from the bottom of the North Sea some years ago and when it was radiocarbon dated estimated to be 28,000 years old. This came as a huge surprise because it had been believed they had died out 200,000 to 300,000 years before. Of course possible something was incorrect with the sample/sampling, but intriguing. It certainly shows our understanding of the past has bloody great holes in it. If humanity had never came along could a cat very similar to the famous sabre tooth be stalking red deer in open woodland on the ‘flow’ country today?

At last the role of tree planting in helping prevent climate change seems to be gaining traction, even among politicians. It seems to me that a key battle for the next few years will be to ensure that the new planting is not once more dominated by exotic conifers, even though I seem to have read that they may store a few more percentage points of carbon per hectare as they grow.

A push for increased planting (or natural regeneration) of a good range of native broadleaves could be a huge plus for conservation. Conversely, blanket afforestation with non-native conifers could be a giant step backwards to the bad old days. Somehow we have to persuade government to do the right thing – no doubt in the face of heavy lobbying by forestry companies.

Those terrible tax avoidance plantations mid Flow Country have one good thing about them. They allow self-sown native trees to colonise within the safety of their deer-fenced boundaries.

Have there been botanical surveys of these ungrazed edge habitats?

Very much agree with Keith Bennett’s vision of getting ‘’some more woodland growing, but it should be native species, locally (in valleys, along the rivers, etc), inter-digitating as naturally as possible with the great wide peatland expanses…”

Lobbying for proper reduce, reuse, recycle and use of recycled material would do an awful lot to counter the case for expansion of plantation forestry anywhere. There would also be far more additional reprocessing jobs created than by increasingly mechanized forestry – so more wildlife, more jobs and a far nicer place to visit and spend money than soul destroying, endless conifer plantations. I wish the conservation organisations would do a far better job of linking the dots than they do now.