Paul Sterry has an academic background in freshwater biology and is a passionate conservationist. He has been writing about natural history and photographing wildlife for the last 40 years, with an emphasis on the British scene.

Back in July a botanist friend from New Zealand came to stay. Anne, my guest, wanted to visit Hay-on-Wye for the books and to see some floral sights in Wales, so we spent a few days roaming around. Hay’s bookshops did not disappoint but I am not sure I can say the same for the rest of the trip. Given that Anne had just spent two weeks botanising in the Swiss Alps, Wales was always going to be a bit of a let-down and in that regard it met expectations.

The best thing on offer was a wonderful little reserve called Vicarage Meadows, a charming little spot maintained by the Wildlife Trust of South and West Wales. Its meagre 3.6 hectares boasted a host of meadow specialities and veritable carpet of Wood Bitter-vetch Vicia orobus, a plant that is in steep decline elsewhere in the UK. The reserve’s integrity is maintained with the aid of a couple of frisky Exmoor Ponies that are allowed access to the reserve proper only when flowering and seeding have finished, with their grazing activities monitored of course. Vicarage Meadows represents a rare glimpse of what Welsh grassland might look like in absence of intensive grazing by sheep.

I should mention that Anne is not only a botanist, but also a third generation sheep farmer from North Island. Hers is the sort of enterprise where you drive for an hour in a 4×4 and still haven’t reached the middle of the farm. So as well as knowing a thing or two about botany, she is also qualified to have an opinion about grazing levels, as well as sheep management and husbandry. Although she was too polite to say much I don’t think she was impressed by what she saw outside the reserve boundaries of Vicarage Meadows.

While in Wales we stayed at a friend’s house close to Blaenavon and just inside the boundaries of the Brecon Beacons National Park. It’s a strange part of the world I have to say with evidence of man’s impact on the environment, past and present, writ large and particularly obvious if you know your flowers (or lack of them). Anne is fully aware that the impact of humans and farming on New Zealand has been little short of an ecological catastrophe. But a walk in the Llanelly Hills offered a reminder that New Zealand is not unique in that regard: our industrial heritage literally reshaped the landscape. A century or so on from the most active use of the land, and vegetation has softened the ravages of mining a bit. But any attempts by the land to overcome its enforced botanical impoverishment is kept in check by the nibbling attention of armies of sheep and the scarred tracks left by quad bikes and scramble bikes. On a slightly positive note, I have previously visited the area in October and the close-cropped turf is truly amazing for waxcap Hygrocybe fungi so at least it’s got that going for it.

On our return to Hampshire I decided that a trip to the New Forest was in order since many of the botanical specialities of the area would be in perfect condition. I admit to having a love-hate relationship with the region. Forty years ago, in its pre-National Park days, I used to think of it as a wilderness to escape to. Nowadays, unless I can conjure up a rose-tinted, blinkered outlook all I see is the impact of humans either directly or through the actions of their animals. On the plus side, it is truly remarkable that the New Forest has survived intact since its inception in medieval times. And whatever the pros and cons of this man-altered landscape it is far better for wildlife than most alternative outcomes – intensive farming or urbanisation for example.

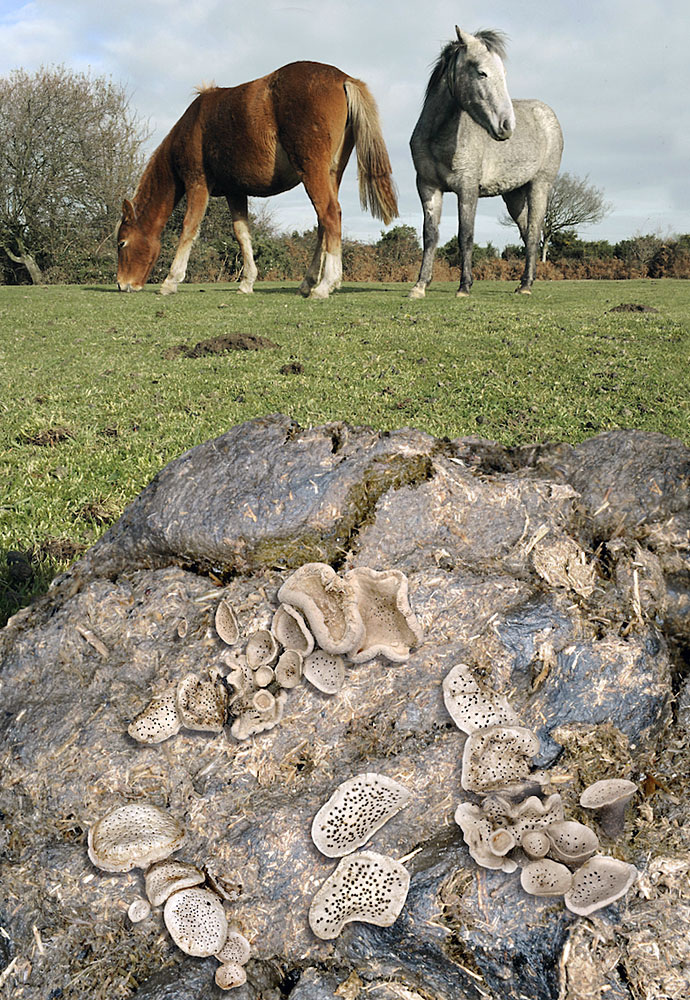

In tree terms, these days the New Forest serves as a testament to the consequences of intensive grazing, the obvious signs being the woodland browse line, bark damaged during the winter months, impoverished ground flora, and a lack of tree regeneration. But on open ground it is the very intensity and heritage of grazing which enables many of the New Forest’s specialist plants to survive – on the so-called ‘lawns’ that are grazed to within an inch of their lives.

Grazing is certainly part of the natural heritage of Britain but nowadays our attitudes towards its role are a bit conflicted. On the one hand it is acceptable (and entirely justified) to bemoan the impact that intensive grazing has on the botanical makeup of the Welsh uplands. But tacitly at least severe grazing pressure is celebrated in the context of parts of the New Forest. Clearly it’s a question of degree, with location and context playing an important role. When it came to the New Forest I suspect Anne was slightly bemused, specifically by the sociological aspects of ‘commoners’ rights, and the obsession with grazing animals. She pointed out that some of the plants I was thrilled to be showing her are problem species in the Antipodes. For example, inadvertently introduced to New Zealand, Pennyroyal Mentha pulegium is considered an agricultural pest and worthy of control. And according to documents listing Australian naturalised invasive plants Yellow Centaury Cicendia filiformis is classed as an ‘environmental weed’ and a ‘major problem’ in a few locations. It’s a funny old world.

What would be called over-grazing in any other context undoubtedly benefits a dozen or so New Forest speciality plants. But my day out with Anne means I find it increasing hard to convince myself that such extreme grazing benefits overall biodiversity. Still I guess we’ll never know because I can’t see the ‘commoners’ ever being willing to give up their ‘inalienable’ rights. At this point, while musing on this point, we were treated to another New Forest speciality – a pack of out-of-control dogs that disturbed the tranquil scene not only for us but for some of the ponies too. My dark humour took hold and I wondered whether any of foals being chased were going to end up becoming pet food to feed their pursuers. Suddenly, nothing seemed to make ecological sense. All in all Anne’s visit was a sobering reminder for me of how much the British landscape and our vegetation is what it is because of the legacy of historical land use and abuse.

Driving for an hour and still not getting to the middle of the farm.

Yes ,we had a Landrover like that once.

insightful as always, makes one think. I moved from the Harrogate area of North Yorkshire to here in mid Wales in early 2018 and whilst North Yorkshire is hardly a pillar of rectitude for a variety of wildlife reasons its flora is at least a little better in both distribution and variety compared to here in Wales, locally at least. Most fields around here are reseeded, some regularly so and much of, if not all the hillsides are sheep trashed with the only areas they avoid being bracken ( does well because they don’t eat it) and gorse for the same reasons. I have to drive some distance to find decent conglomerations of native plants.

Of course this botanic impoverishment does not just affect the plants themselves, it damages badly the insect fauna and hence all the way up the food chain birds in particular are not doing well here barring a few obvious species. Time much of this was sorted out properly if necessary through prescriptive and agricultural payments. There are many ways the folk here could make good livings from the land without quite some much ecological cost and damage.

” There are many ways the folk here could make good livings from the land without quite some much ecological cost and damage.”

No propblem then – rent a farm and show us?