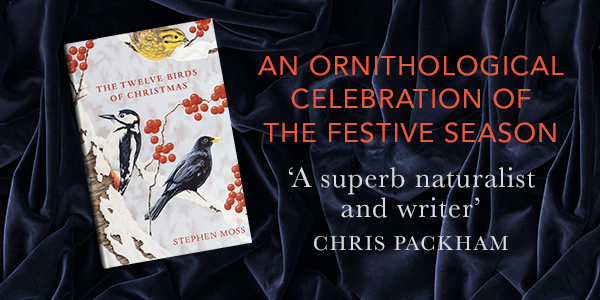

Stephen Moss has written a round-up of nature books for many years and this is the second year when it has appeared here on this blog. Stephen is course leader of the MA Travel & Nature Writing at Bath Spa University. His latest book, The Twelve Birds of Christmas, is published by Square Peg (£12.99). @stephenmoss_tv

Insects are in the news, following a recent report that highlights their worrying declines. The author, Professor Dave Goulson from the University of Sussex, has also produced a lively and engaging book on what we can do to help, The Garden Jungle (Jonathan Cape, £16.99). Wildlife gardening is also at the heart of Dancing with Bees, a delightful combination of memoir, history and practical advice from Brigit Strawbridge Howard (Chelsea Green, £20).

The gaudiest of insects, moths and butterflies, feature in Peter Marren’s wonderful Emperors, Admirals & Chimney Sweepers (Little Toller, £30), in which the veteran author shares his lifelong appreciation for the names of these charismatic creatures. Those names sing out from the pages of the revised second edition of the moth-trapper’s Bible, Concise Guide to the Moths of Great Britain and Ireland (Bloomsbury, £16.99), worth double the price for Richard Lewington’s remarkably accurate and beautiful illustrations of almost 1,000 species.

For those who want to know even more about lepidoptera, there are two seminal publications just out. Life Cycles of British & Irish Butterflies, by Peter Eeles (Pisces, £35), is an extraordinary achievement, and will be a benchmark for decades to come. Also from Pisces (one of those publishers who, like Little Toller, punch well above their weight), is the forthcoming Atlas of Britain and Ireland’s Larger Moths (£38.50) – the synthesis of 300 years of records, showing the plight of many of our most charismatic moths in this age of the Anthropocene.

Other authors focus on the environmental crisis we are facing and what we might do to reverse it. One huge barrier is the concentration of our land in the hands of a small group of aristocrats, landed gentry, industrial-scale farmers, the church and large corporations. Enter environmental campaigner Guy Shrubsole, who has painstakingly unearthed the facts behind land ownership in a Who Owns England (William Collins, £20). This is nothing less than a modern-day Domesday Book, and should be required reading for politicians, environmentalists and anyone who cares about the future of our countryside.

More specifically, The Missing Lynx, by Ross Barnett (Bloomsbury, £16.99) examines the reasons why we should bring back this elusive wild cat to Britain; the argument is a coherent and compelling one – yet still the vested interests revealed in Guy Shrubsole’s book stand in the way of it becoming a reality.

On a global scale, Working with Nature, by Jeremy Purseglove (Profile Books, £14.99) clearly sets out how we can both protect and restore the Earth’s natural resources before, as the old cliché goes, it is too late.

Reading these books sometimes creates a feeling of impotence, as we wonder what we can do to help. Perhaps the first step is to engage – or re-engage – with wildlife on your doorstep. The young environmentalist and campaigner Lucy McRobert provides exactly what we need, in 365 Days Wild (HarperCollins, £16.99). Subtitled ‘A Random Act of Wildness for Every Day of the Year’, this is a practical guide to rewilding ourselves, with a particular focus on things that will also fit in with our busy lives – so no excuses! The book’s dedication – ‘For my mum, Alison, and my daughter, Georgiana. I wish you had met.’ – hints at the crucial importance of nature as a way of healing our lives.

Another book which puts nature’s healing powers at its centre is Bird Therapy, by Joe Harkness (Unbound, £14.99). The author’s story of how engaging with wildlife helped him overcome his mental health issues and get his life back on track is uplifting and informative; why no mainstream publisher was interested in this (it was crowdfunded by friends and supporters) is baffling.

Amidst these more topical offerings, the heavyweights of the natural history publishing world continue to maintain the highest standards. Just two new titles in the classic New Naturalist series this year: Gulls, by John Coulson and Garden Birds, by Mike Toms (HarperCollins, both £60 hardback and £30 paperback). Both show a real breadth of scholarship, with Mike Toms’ volume standing out as one of the best NNs of recent years. Reaktion Books continue to bring out fascinating small volumes on individual species: I loved Kingfisher, by Ildiko Szabo (£12.95), which like previous volumes in the ‘Animal’ series is packed with an eclectic mix of science, history and folklore.

Mark Carwardine has produced what might be the definitive work on the world’s cetaceans: Handbook of Whales, Dolphins and Porpoises, by Mark Carwardine (Bloomsbury, £34.99) – a remarkably detailed guide which will take its place on every wildlife-watchers’ shelf. And Lynx Edicions have finally reached the end of another epic series: Handbook of the Mammals of the World: Volume 9 – Bats (£145). The achievement of this Barcelona-based publisher, first with their 17-volume Handbook of the Birds of the World, and now with an equally detailed and thorough series on mammals, cannot be overestimated. They may be expensive, but the wealth of information, illustrations and photographs they contain makes them well worth the money.

Amongst all this information and scholarship, is there still room for classic ‘New Nature Writing’? I would say yes, but there are noticeably fewer offerings than usual. Two relative newcomers lead the way: Stephen Rutt with The Seafarers and Wintering (both Elliott & Thompson, £14.99 and £12.99) and Tiffany Francis with Dark Skies (Bloomsbury, £16.99), all three of which bring a fresh new perspective to a genre in danger, perhaps, of flagging.

Another new and refreshing voice comes from my colleague at Bath Spa University, Gail Simmons, whose debut work The Country of Larks: A Chiltern Journey (Bradt, £11.99) retraces the steps of a young Robert Louis Stevenson on a walk through the Chilterns – coincidentally along what is now the proposed route of the HS2 railway line. Her gentle yet incisive style of writing, and the voices of those she meets during her walk, create an elegiac tribute to this soon-to-be-destroyed corner of the English countryside.

But more established writers and artists are still producing excellent work: notably Underland, the latest offering from Robert Macfarlane (Hamish Hamilton, £20), and

A Sparrow’s Life as Sweet as Ours (Bloomsbury, £20) – a collection of John McEwen’s columns from The Oldie magazine, beautifully illustrated by the incomparable Carry Akroyd.

Meanwhile, two of our most respected environmental figures – the godfather of nature writing and one of our most respected broadcasters – have produced works of autobiography. Richard Mabey’s Turning the Boat for Home: a lifetime of writing about nature (Vintage, £18.99) collects his life’s work into one single, very special volume; while Headlines and Hedgerows: A Memoir, by John Craven (Penguin, £20) is, as you might expect, a very readable account of a remarkable life.

As is one of the most unusual books featured here: Neville Chamberlain’s Legacy, by Nicholas Milton (Pen & Sword, £25). You might wonder what this volume, subtitled ‘Hitler, Munich and the Path to War’ is doing in a round-up of books on nature and the environment.

Yet like so many other politicians of his era, including Edward Grey and Lord Home, Chamberlain had a deep passion for the natural world: especially butterflies. As Nicholas Milton points out, not only did this much-reviled political figure help drive the relatively new nature conservation movement in Britain, and go birdwatching in St James’s Park almost every day of his time in office, he even had a species of butterfly named after him – Chamberlain’s Yellow – from his time spent in the Bahamas as a young man. Fascinating stuff.

Which brings me to my book of the year. As ever, this was a tricky decision to make, not least because of the range and scope of so many of 2019’s publications. I was tempted by two epic offerings, the Handbook of the Mammals of the World and Life Cycles of British & Irish Butterflies; and also by more personal offerings such as Bird Therapy and Turning the Boat for Home.

But ultimately one volume stood out: a book on an urgent and topical subject, written by a young debut author and published by a small but very professional publisher: Rebirding, by Benedict Macdonald (Pelagic, £19.99).

I must confess an interest here: I have known Ben for a decade or more, and watched his progress with interest and not a little pride. What he has done with Rebirding is to ask a simple question – what if? What if we decided that we really did think that our wildlife deserves a place in the wider countryside? What if we worked with landowners and rural communities to show them just how much economic benefit it would bring, with the statistics to prove it? And what if we then decided to actually make the changes that would bring about such a visionary future?

Rebirding is a remarkable book – a manifesto that doesn’t just tell us what has gone wrong, but also how to put things right. Whoever emerges as the new government after December 12th should adopt this as their policy for rewilding Britain, for the benefit of us all.

Hi. Maybe it was published too late to be included (Sept 2019), but my book Wildlife Of The Pennine Hills (Merlin Unwin), written in conjunction with Tim Melling, isn’t mentioned. Maybe next time?

Doug – I’ll probably mention it if you send me a copy.

Well that’s my reading list decided for the New Year! I have to agree that ‘Rebirding’ really stands out as an exceptional work – it’s so on several levels. Ben simultaneously manages to put across an incredibly detailed ecological picture of how habitats function properly and how they don’t then manages to do the same level of analysis with the ‘economics’ of driven grouse shooting and open hill deer stalking. It really is a unique achievement. I’ve got a soft spot for ‘The Missing Lynx’, the author wrote how in childhood he was mainly interested in dinosaurs until he realised that the lost giants of the ice age were far more relevant to us and our world, our ancestors saw, ate and painted them and without us they’d probably still be here. That’s exactly what happened with me, I used to day dream about Irish elk in particular, magical.

Purseglove or Pursglove

What a difference an e makes!