At lunchtime I wrote of some errors of avian population trends in Magnus Linklater’s recent opinion piece on the demise of the Curlew. It’s a good example of how all opinions are valid, but that facts are sacred, and that if your opinion doesn’t fit with the facts then maybe you should rethink.

By the way, I do think that predation is a serious problem for Curlew populations and that’s why I have never argued against targeted predator control to help Curlew and a few other declining species. But it’s the Red Fox which needs to be targetted the most, and only in some places. With a decline like this …

…then Curlew do need some help, but that ought to be science-led helpful help and not misjudged help.

So let us turn to another quote from Magnus Linklater’s piece;

For us there has been no change in land use. There are no crops round here because we are too high up, and the ground is mainly moorland so no pesticides have ever been applied. There has been no ploughing or drainage and the sheep flock is much the same size as it ever was. There are ramblers and dogs, but it would be hard to lay the blame at their door.

https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/mourn-the-birds-lost-to-unchecked-predators-trlwp7swv

Fair enough, I’m in no position to question the details of Mr Linklater’s back garden estate, but the bigger picture, is that there have been massive changes in farming practices overall and carelessly Mr Linklater misses out that very change which is most likely to have made a huge difference to Curlew numbers since the 1960s about which he reminisces with such emotion for the lost Curlew. And that is silage making.

Curlews often nest in grasslands – not always, but often. They used to nest in hay meadows and still do where the meadows exist. Hay meadows used to be cut at the end of the season, once, for hay, and that would be long after the Curlew (and Corncrakes) had hatched and moved on. Now even hay meadows are cut a couple of times in the season but many grass fields are cut three times for silage. You must have seen those big bale plastic sacks in fields or piled up in farmyards. That is the modern efficient way to produce more food for your livestock in winter.

Every time I see them, even when coloured pink to support breast cancer, or with smiley faces on them, I see bags of dead Curlews and other ground-nesting birds – not literally (although up to a point literally) but metaphorically. Curlews get mown with the grass in silage fields.

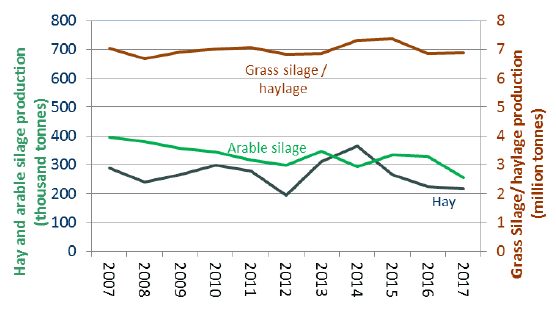

Now I’ve been looking for some nice graphs on silage produuction but they seem a bit difficult to find (help please!) but I have found a melange of information to back up what I am saying here.

First, this paper:

…which has this abstract:

…which tells us, as I thought I remembered, that silage making really took off after WWII when there was ‘a huge increase in the tonnage of silage made’.

The current situation in Scotland, though not necessarily in Mr Linklater’s neck of the woods (though I bet it is), is that grass silage and haylage now make up about 75% of the total hay and silage production in Scotland. Before WWII that figure was close to 0% and now it is close to 80%.

It’s funny that a real country person like Magnus Linklater forgot to mention this fantastically major and important land use change that is blindingly obvious and which affects the Curlew – maybe because it’s one that can’t be solved by shooting Red Foxes or the declining Hooded Crow?

[registration_form]

It isn’t just how much silage but how much earlier the first cut is. Not just bad news for Curlew but so many ground-nesting birds.

And Hares? I had something of a debate with a farmer I was visiting during the course of my daily clinical work and I had to apologise for being late. My excuse was I had stopped on this very rainy day to check a bedraggled looking Buzzard at the side of the road which I thought was injured. Fortunately it flew away as I drew near and I realised it was merely enjoying a feast of pheasant! When I explained the cause of my tardiness to the farmer I was instantly admonished for my effort and received a lecture from him on the appalling state of the countryside due to it’s over-population by badgers and “winged vermin” like Buzzards. The latter I was informed were the most significant contribution to the reduction in the Hare population essentially because they prey upon Leverets and that was “why, young man you’ll hardly ever see any Hares these days”.!! Buzzards according to him should be shot on sight! When I suggested that a contributing cause of Leveret decline could be silage production and that Leverets were likely to end up chopped to pieces by forage harvesters I was almost shown the door!

Hi Mark

There are a couple of graphs in this 1996 paper, though you’ve probably already seen it: https://www.bahs.org.uk/AGHR/ARTICLES/44n1a5.pdf

Shifting baselines again. The huge drainage programme from the 50s to 70s has disapeared from the collective memory but had turned large areas from grass to arable and played a big role in current flooding problems. Almost all upland areas have seen intensification moving up the hill – it may just look like grass to you, but the e ological difference between semi-natural grassland and reseeded, nitrogen fertilised ryegrass is extreme. It is also very unlikely that sheep density hadn’t oncreased in the last 50 yeras – but then, to the untutored eye the landscape looks much the same and if it doesn’t, the change has been far too gradual to notice.

At what point are the foxes paying the price for all that silage?

If you conduct predator control to try and boost the productivity of the few remaining pairs of curlews aren’t you just opening the door for the Magnus Linklaters of this world to go about killing everything in the name of conservation?

The real solution is the one that replaces intensive silage production with hay meadows. If that’s unacceptable for reasons of food production then it’s time we grew up and accepted responsibility for it rather than trying to fix the problem around the edges with all kinds of collateral damage as a result.

The problem is dairy farming

It’s horrendous. From production of silage to cows confined 24/7 – the whole industrial process of making milk has no benefit enviromentally/ecologically/ nutritionally

There are papers linking dairy products to cancer particularly breast

In the beginning there were foxes, there were curlews. There was no silage.

Another aspect of silage is the continuous spreading of slurry after every cut. An 800 acre intensive dairy farm I’ve spent 20 yrs exploring once had a pair of Curlew on the lower meadows. They now silage 3 to 4 times a year to fill the silage clamps and in between the cutting inject effluent using umbilical pipes direct from the lagoon. The last time the curlews nested a friend put two pegs well wide of the nest so the slurry spreading tractor could avoid the nest. They were essentially nesting on an open green desert though!! Sad times

There are two critical points here.

Firstly the vast hectarge of land that is cut 2 or 3 times a year in the upland in-bye for silage. In the largest lowland LFA in Devon, 5 cuts a year is recorded, in zero graze dairy units, which a generation ago supported breeding curlew.

The other, which received less attention, is the fact it is an intensively managed monoculture. Species rich meadows full of invertebrates lost to the plough, under drainage, prg, lime, and bags of 20.10.10.

It is a problem with silage that only farmers understand.

Much heavier crops

Probably harvest 100 acres in two days as opposed to at least a week for hay plus the risk of rain during that week.

Even more important the nutrients in silage is so much better than hay.

The answer if there is one has to be found accepting silage making is likely to stay as long as we farm cattle.

The problem is much bigger actually than just Curlews there are other birds affected worse.

Hi Dennis. I don’t think it is only farmers who understand the reasons for the change from hay to silage production. I don’t think any sensible person thinks farmers switched to silage on a bizarre whim or for some malign desire to eliminate curlew and corncrakes from their land. They switched because silage offers significant advantages to livestock farmers – as you explain – and the harm to curlew populations was an unintended consequence. But it was a very real consequence and coupled with other improvement measures – rye grass leys, drainage, artificial fertiliser usage, etc that permit multi-cropping in the same year it has proven to be catastrophic for most of the wildlife that once survived within hay meadows.

Recognising the problem and devising a solution are rather different things however. The industry is not going to revert to hay making on a significant scale. Small areas of traditional hay meadow (a minuscule percentage of the former area within the country) have been maintained by stewardship payments and it is to be hoped that in some form these payments will continue post Brexit. It is also possible that the changing economics of farming (including the subsidy structure) post Brexit will result in significant areas of land falling out of intensive production and this may provide opportunities for nature conservation, including curlews.

Jonathon, think we are in agreement.

Where I may differ from most is that in my opinion the whole population except that small % who do not consume beef or use dairy products or leather are in a way just as responsible as dairy farmers because make no mistake there would be no cattle if their was no demand for the products.

“It is also possible that the changing economics of farming (including the subsidy structure) post Brexit will result in significant areas of land falling out of intensive production and this may provide opportunities for nature conservation, including curlews.”

Very likely in the uplands I would suggest. Once the direct pillar 2 subsides are withdrawn I foresee big changes ahead. Some dairy farming will continue on some of the more favourable land, but I just can’t see many of the more intensive beef and sheep enterprises continuing in the same vane.

In the miserable summers in 50s & 60s farmers got tired of making & feeding mouldy hay and getting farmer’s lung and cattle got tired of eating it. Ensiling grass is a more reliable way of conserving grass for winter feed than weather-susceptible haymaking and allows high yields of high D-value feed. D is the content of digestible organic matter in the DM and it falls off a cliff as grass matures after flowering although DM continues to accumulate.

Silage effluent seriously pollutes water if it escapes but improved techniques have reduced the incidence of incidents. Baled haylage is a reasonable compromise that ticks several boxes.

Unfortunately there are several aspects of forage maize production that also tick big boxes but personally I would like to see maize cropping cease altogether on this side of the Channel. T’aint right t’aint fair t’aint fit t’aint proper

Surely the main driver for the decline in curlew numbers is the loss of habitat due to afforestation of the uplands? Not only is the habitat lost but the forestry plantations also serve as a repository for foxes.

Wind farm developments will hardly have helped the cause either.

Which begs the question: before the neolithic deforestations where did the curlew live? I’ve often had the same thought about arable weeds.

Bearing in mind that curlew only started breeding in lowland habitat about a century ago who is to say where they bred 5,000 years ago. Their fundamental requirement is soft ground to feed on, and I suspect there was plenty of that around.

I’m pretty certain that across the UK less grassland fields are cut – either for silage, haylage or hay compared with 10 years ago as more livestock farmers, particularly dairy farmers, have switched to a low-input, low-output grass-based ‘extended grazing’ systems. This involved smaller lower yielding cross-bred cows that are long-lived and better adapted to grazing for 9-10 months of the year, and not requiring large quantities of bought-in concentrated feeds. These farms only need ‘expensive’ grass silage to feed cattle inside for 1-3 months, hence the silage acreage is significantly reduced.

Grazing practices are changing also. Less set-stocking and more rotational paddock / cell grazing. The grass on some of these farms will never be long enough to provide any cover for curlews, then there is the risk of trampling..The impact of which needs to be properly quantified – there will be winners and losers.

Hay is an increasingly high-risk activity with climate change, in my part of the NW hardly any was taken in 2017 as although growing conditions were superb, we barely had any 3-4 day windows of opportunity needed for hay-making. 2018 provided several months of perfect hay-making conditions, just a shame there wasn’t any grass there to be cut. 2019 was a disaster for those who left it too late, those who cut in early-to-mid July made some good quality hay, those who didn’t watched their meadows collapse and start rotting – unless they managed to pinch some haylage here and there if they could dodge the weather.

As a rule, I don’t come across that many farm upland farms that take multiple silage cuts, usually because its not very economic to do so, and because growing conditions are not particularly favourable.

In the 80s, to read the farming comics, you might have thought 3-4 silage cuts were the norm. On asking many farmers, this was not the case and 1-2 or 1+grazing were typical. In late 70s there were some Dutch experiments with 7 cuts and 1000kgN/ha/y so maybe we dodged that bullet.

I recently came across an ICI booklet from the early 80’s and was astounded by the nitrogen recommendations, >400kg N/ha for a 3-cut system with late-season grazing.

It’s a shame more conventional grassland farmers don’t take a leaf from their organic counterparts book. Some organic farmers are getting up to 14t DM/ha from IRG/red clover leys and up to 11t DM/ha from PRG/white clover leys. Lucerne pretty useful as well, I’ve heard of some growers getting over 15t DM/ha.

I guess at that time N was too cheap & marketing could target maximum yields rather than the economic optimum. Nif is pretty much a no-brainer. No doubt we will hear more about best methods for conservation of herb-rich mixtures with time.

I had a similar thing from a local farmer who blames the declines in the local Lapwing and Curlew population wholly on Badgers. Of course it’s likely to be a combination of factors, agricultural practices prominent among them, but it’s far easier to blame a wild animal (especially one that inconveniences you in other ways) and suggest a simplistic solution (e.g. a cull), than deal with the inconvenient truth that your own activities could be implicated.

David, not sure disease free Badgers are a inconvenience. I think farmers in general as opposed the the two examples on here enjoy seeing Badgers and wildlife in general as they see it more than most of the population.

In all populations you will get a variety of attitudes.

We had a pair of curlews nesting here for many years – not far from Huddersfield but not on the moors. The farmer then didn’t make silage but let his cows graze the fields. When he retired & sold up about ten years ago, the incoming farmer intensified, massively increasing the herd. These fields are no longer grazed but silage cut at least 3 times a year, slurry spread for months on end, herbicide & pesticide applied too. The curlews visit every spring but no longer stay to nest. This year there is only one lone swallow as there are no insects. There are no larks now & the yellowhammer nests are wiped out too. Hares are now rare – even the poachers don’t think it worth the trouble to come lamping. Advice from RSPB isn’t working. Subsidising intensive cattle farming should stop – they spend most of their lives in sheds. I agree that consumer habits also have to change. What little dairy food we eat comes from sheep & goat milk. We don’t eat meat – it’s an unhealthy food to force on your family. But politicians are afraid of agri-business strength. We need economists to demonstrate that the cost of the heavy machinery, pesticides, herbicides, fertiliser & so on, are only sustained by subsidy & that this method of farming is not economically viable.

Lulu – that’s a sad story and very typical of many places.Thank you for your first comment here.

Totally agree, what a sad and greedy world we live in.