Ben Macdonald is a conservation writer and television producer. The paperback of his book Rebirding is now available from £8.70 here. Twitter: @Rebirding1

Imagine that you want to upgrade your car. You walk into a showroom. There are three models available – all with various degrees of rust. The showman explains at great length that these are the only three models available. Each has a few minor advantages over the other. All are fundamentally broken, not fit for purpose and increasingly, economically unviable to run. You would, of course, walk out, muttering under your breath.

When it comes to managing English uplands, however, this baffling and odd situation plays out on a weekly basis in discussion between conservation and game-keeping NGOs, landowners, the public and various interest groups from the hunting and shooting fraternity. Three models are put forward. All are broadly defunct, and none are widely practised in the hunted uplands of France, Spain, eastern Europe, Fenno-Scandinavia, Canada or the USA.

The first model proposed (in no particular order), is blanket single-species forestry. Increasingly, a range of conservationists, hunters & shooters (but not many commercial foresters, whether private sector or public) align on the fast that dense, festering ranks of spruce trees are a poor outcome for the uplands, the public and most of all, for biodiversity. Several forestry papers exist to show that these forest environments can support some life. Crossbill, red squirrel, siskin, coal tit, goldcrest and others all provide a feeble chorus of birdsong in these dank and largely silent crops of wood. But as with many decisions in our uplands, few other countries have sought to follow suite. In Germany, just 5% of forestry comes of non-native trees. Instead of creating clear-fells that resemble bombing raids on spruce factories, many European countries harvest selectively by thinning. Yet the most interesting fallacy of all is that we need spruce at all. At present, we do, but this is in part because the mills we have are set up for the harvesting of spruce. In truth, there are two tree species that would dramatically increase biodiversity and landscape heterogeneity – and these are European pine, and birch. Birch is a common forestry tree in Scandinavia: it is also one of the most powerful agents of biodiversity and critical for species like black grouse.

Our native trees compute to a far wider range of wildlife, and do not preclude hunting. If our valley sides were rich in birch-woods, we would see resurgences in species as diverse as black grouse, woodcock & cuckoo, whilst resurgence in Scottish pine forestry, would cater for large new areas for capercaillie, golden eagle, crested tit, green sandpiper and many others: outcomes that blanket spruce does not provide. So in the ongoing search for common ground, replacing spruce forestry with birch & pine forestry, would please hunters and ecotourists alike. Capercaillies would be thrilled. Yet so often, the lacking ingredient in these discussions is simply ecological imagination. Because ‘this is how the UK does forestry’, timber lobbyists now clamour for spruce. Rather than basing forestry plantations upon biodiversity and natural processes, and perhaps recognition that open, native woods suit hunting interests better, a large part of the forestry lobby continues to push for more of the same – whilst creating arguments that really, deep down, birds love a bit of single-species monoculture.

The second model, even more entrenched and often beloved as a bucolic idyll, is the standard form of intensive penned sheep farming in the uplands. This is far from the only form of UK upland farming – but over centuries, it has become predominant. Yet as our own history books, paintings and the hills of northern Spain remind us to this day, there was once a species eminently better suited to our uplands: a native one – cattle. Free-roaming hill cattle, if devoid of avermectins and allowed to wander in small herds, can be one of the most powerful agents of biodiversity, because their actions better recall wild grazing processes now lost to much of the land. Paintings of the Lake District 200 years ago show that it was far from the pea-green, uniform green lawn we see today. It was more akin to the hills of Spain or the Alps; a wood pasture landscape, interrupted by cattle and undermined by pigs. Small meadows grazed over the winter became corncrake-rasping meadows by summer. Animals were moved constantly. Wooded margins held wrynecks; scrubland stands, breeding red-backed shrikes.

Through the perverse incentives given to hill farmers over many years, the glorious sight of horned cattle in small, wilder herds, being shepherded through the landscape, is increasingly one that has been forgotten. Yet that, once, was the ‘norm’. Some inspired farmers, like James Rebanks, are now seeking to return to this way of farming. But often, those who do not want blanket forestry forget that sheep is not the only other outcome. Indeed, if we can find the means to get input-free cattle back onto our hills, and phase sheep off (in some areas), the outcomes for both conservationists and hunting lobbies would be dramatic. We know that cattle in the Galloway Hills were once powerful guardians of the curlew; maintaining the richly varied sward they need to feed in and nest in, whilst dung beetles can form a crucial part of curlew diet. Worming chemicals are one of the forgotten aspects of curlew decline – by turning cattle into mobile pesticide-units filled with avermectins, we have removed their crucial ecosystem role as a creator of dung beetles: curlew fodder. At the same time, extensively grazed cattle are an excellent outcome for black grouse – maintaining large areas of open grassland whilst not preventing the formation of areas of scrub, birch, juniper and rowan. This “Spanish Hills” or “Italian Alps” model of farming, still widely seen abroad, is also one that, where practised, could lead to a resurgence in a range of wild game.

This, then, brings us to the third knackered model of the uplands: the driven grouse moor. Not the only kind of grouse moor available, it is nonetheless the most prevalent, and because no other, more visionary hunting models are currently available in most of England’s uplands, “shooting” and “grouse moors” have become, for many, irrevocably intertwined. As a result, a lot of shooters and hunters with genuine interests in conservation and biodiversity (and yes, these exist) feel honour-bound to defend what is, in truth, a strange form of farming grouse invented early in the 19th century. Normally, we tend to upgrade and improve inventions in our country. We are, for example, no longer schooling our children in towering rooms where they cannot see out of the window. Nor are we using horses and carts to get around. Now, it’s long overdue that our hunting estates get an upgrade as well – and again, this is where imagination comes in. Far from a desultory choice of blanket spruce, blanket sheep or blanket grouse – the three rusting models that we are told we must choose from – we must instead look overseas for the real solutions.

Overall, grouse moors occupy just under 8% of the UK landmass. This gives them the scale to strive towards far more visionary outcomes – outcomes that need not preclude hunting at all. One obvious example is the expansion of quarry species. The intensive grouse moor is fantastic for those who like to be driven up a hill and don’t want to miss. This living clay pigeon shooting has been looked at in a range of other countries, often with bafflement and bemusement. I explained the concept some years ago to an Alaskan hunter & shooter, who had a choice of four grouse species, three deer, elk and brown bear to hunt from on his land. He said simply, ‘that’s not a field sport, and it’s not sporting’. For those who enjoy the chaos of downing 100s of objects very fast, clay-pigeon shooting already exists. It’s a lot of fun.

In most countries, hunting estates are more often areas of native, near-natural habitat. In Spain, cork oak woodlands are often well-protected by hunting estates. The income from boar and deer hunting also allows large areas to be protected for the Iberian lynx. In Scandinavia, rural areas of low population density are given value through hunting a range of quarries, crucially, across the year. Large areas of Tanzania, such as Ruaha and the vast Selous, simply would not still remain as wilderness without hunting income. Others, like the Maasai Mara, are now powered entirely from ecotourism, generally a far more widespread generator in the rural economy, when given a chance. Lions, once slaughtered in the conservancies, are now worth far more alive than dead. I use these examples to illustrate that if implemented correctly, the dual protections of ecotourism and hunting can act in sync to protect land from intensive farming or, worst of all, concrete. If there is one extraordinary reminder that this was once the case in Britain, try a day’s walking in the New Forest: the oldest hunting estate of them all.

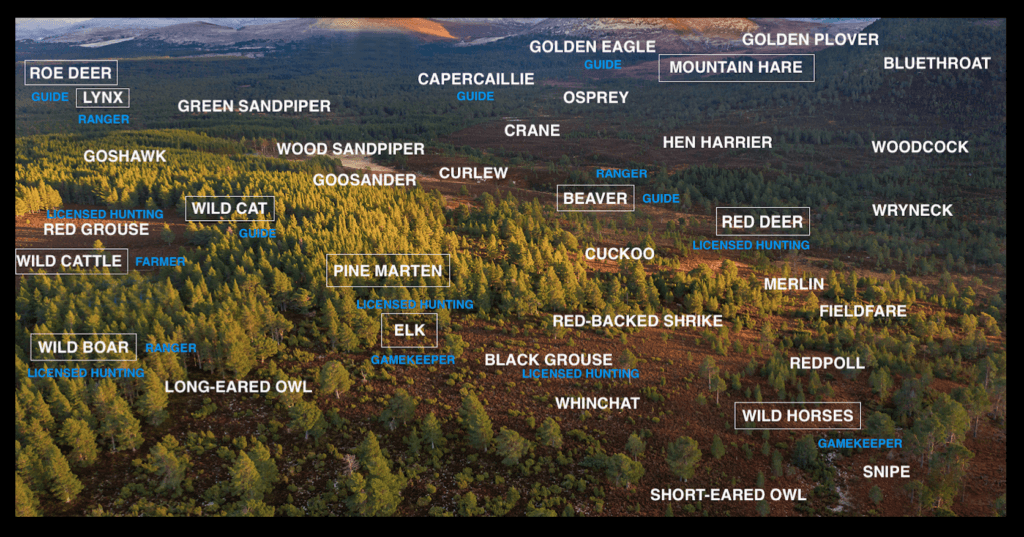

When it comes to the uplands, we often present ourselves with false-opposites that are often the form of a deeply entrenched lack of imagination – and this not only amongst hunters and shooters but conservationists as well, and the many who straddle both sides. In truth, if we turned our burned, knackered and discredited driven grouse moors into naturally-wooded areas like the New Forest, but used native herbivores to keep large areas open (most species preferring a mosaic; some, like the curlew, preferring things open), we would resolve a lot of issues at once. In a mixed mosaic landscape with wild grazing animals, a whole range of outcomes become possible at once. Birch and pine can be harvested – but the landscape does not bow solely to that pressure. An ever-growing number of species can be hunted sustainably (black and red grouse, red deer and eventually, in larger areas, boar and elk). And free-roaming cattle can add farming jobs and a source of sustainable grass-fed meat. Critically, long forgotten ecosystem engineers such as wild horses (a species universally loved by the public), are the agents that once prevented our hillsides from burning at all. By removing huge quantities of dry, dead matter as their culinary default, horses are at once the creators and protectors of upland open grasslands for declining species like the curlew. Indeed, as free-roaming ponies have vanished from many southern uplands, so curlews have vanished as well. Such interdependencies are ancient and profound. Long before the grouse moor, long before humans colonised Britain, cattle, horses and elk would have played critical roles in the protection of what are now termed moorland birds.

This proposition of a mixed mosaic upland, what some might term a ‘fantasy landscape’, is simply the norm in many European uplands I have travelled to. It can work here, too. We have the space. Between us all, we have the will. And this is a vision that doesn’t preclude ecotourists or hunters, foresters or farmers. It is a vision that doesn’t require radical social change (though I respect the views of those who say we need it) – and most of all, it would work in the interests of both landowners and the public. There is no fundamental reason that we cannot manage our uplands as semi-wild, mixed mosaics. Except one. Imagination – on all sides.

[registration_form]

If you were designing a strategy from scratch, and looking to other countries for inspiration, your vision for the uplands is the obvious one to choose. But making it happen given all the history, land ownership issues and polarised attitudes here will be tricky.

A flagship example on a sufficiently big scale would help. But away from areas that already have some conservation value, mostly in Scotland, even this appears challenging.

Strangely, in England there seems to be more progress in the lowlands with great fen project, Somerset wetlands, Knepp etc though all suffer from being too small and stuffed full of people. They are all a bit ‘theme-parky’ though still inspiring places for wildlife. Your multi-use model would be challenging at any of these places as the hunters would risk interfering with the wildlife watchers.

We need a huge upland project starting from open moorland but that seems a long way off, and will no doubt take decades once started. It’s going to be a long haul!

Ian – why aren’t our National PArkls more like this vision? Why didn’t the Glover Review say that they should be?

It’s a bit like wildlife legislation. It you could start from scratch it could be so much more sensible, coherent and easy to understand. But it’s been cobbled together, having evolved gradually over time, bits added here and there, ending up with the mess we have now. It’s similar with the NPs. The land-use, ownership, attitudes, legislation etc have all developed in a piecemeal fashion over time. To get to Ben’s vision requires much of this to be unpicked, so far from easy. Well worth aspiring to though.

Ian – agreed, and Glover review was the place to signpost all of that but it failed.

Thanks for engaging Ian, I do think it will be tricky but perhaps not as much as you suggest. Ecologically, if you take an area like Bowland, you already have the space. Trees tend to look after themselves. Herbivores tend to ensure the trees do not have it all their own way (excuse the simplification but this is broadly true). Keeper roles would transform but not be lost. There would be net biodiversity gain, hunting would remain. Really, you are seeing a 2D habitat, intensively hunted, transform into a 3D habitat, extensively hunted. That’s a 15-20 year ecological process before you begin to see massive change, and perhaps as little as 25 years growth before elk becomes possible. Hard? Yes, but the ecology is the easier part.

Maybe why projects like Langholm need to succeed. Many different buyouts all with their own ideas.

Hi Ben,

I enjoyed your blog and also your book ! I agree we need more balance in managing our landscapes and need to return to a more natural way of doing things. What are you thoughts about the increasing tick numbers we are getting in the uplands and their devastating affect on ground nesting birds? Is there a way in your model that they would naturally reduce them? Using cattle to graze untreated ( though I’d like to) could exacerbate the problem by adding another untreated vector. I think ticks are going to be a huge issue to resolve to enable your wilding aims to work well.

I’ll probably be shot for straying in to such hostile territory… but the good news is that change is happening and rather rapidly in lots of places in the uplands (though it is rarely seen or understood by our critics), and the thinking of the more enlightened farmers (as they learn more about ecology, grazing best practice and soil health) and the more pragmatic rewilders (as they accept the need for management and grazing even in ‘wilder’ systems) is getting closer. I like Ben and see a lot I can work with in his book, I’d simply argue that if we want an inspired mosaic of habitats then fences are the simplest way to mix up management – and fencing the uplands or commons in to a mosaic isn’t being stopped by farmers, many of whom manage mosaic habitats on their non common land with great success, but by legislation and the landscape protection lobby. On my own land I can give you areas of thorny or willowy scrub or wilder riparian areas, or new grazed woodland, etc etc but on a common I can’t. I’d also gently suggest that the best way to make this happen is to help upland farmers to learn and understand these issues, and the worst way is to attack them – if you simply give them a bogeyman you empower the reactionary elements in that community and weaken those speaking for change and sensible compromises. Radical big mouths on one side create reactionary big mouths on the other.

James – thank you, sounds good to me.

Some truth in this but I think much of the opposition is contrived by those who wish to keep things as close as possible to what they are now. Even the word ‘rewilding’ is seized upon as supposedly hostile because it can mean so many different things. Yet everyone is happy with the term ‘farming’, despite the fact that is covers many different activities.

I’m not sure how much can be achieved by a softly, softly approach given the massed ranks of vested interests. Small gains maybe working with those who care but we really need things to happen on a huge scale.

Iain – no one is happy with the cavalier use of the word ‘farming’ – quite the opposite

For exactly the same reasons – I think you need to talk to more farmers

Shot no! Applauded yes, because you are actively trying to do something constructive and not just typing words into a computer from your bedroom.

Yesterday was a momentous day for us, the final jigsaw piece in a huge project was completed, the installation of a entrance cattle grid, this meant that the whole farm is now completely departmentalised by fencing. The cows have total access to the whole farm, woods, meadows, rides, fields, and coppices, they can now eat and poo to their hearts delight. By means of ride gates these animals can be controlled on how much they eat, where and when.

Knepp had a grant to get this fencing done; it was the catalyst to their major rewilding project – unfortunately for us these grants are no longer available.

The cattle are the key to biodiversity; by allowing free access they should increase everything across the board. The farm already get entomologists, ornithologists wetting their pants when they visit, so fingers crossed this action is just adding to our species list.

The cows are important, bison or water buffalo would be great, but the fencing cost needed for these would be even more astronomical. If anybody saw Springwatch and the Knepp story you’ll have seen the landscape they create, the shrubby habitat patches are perfect. Less perfect was the closely cropped grass, in fact Knepp’s grassland diversity isn’t great, if I were to walk Knepp’s fields and ours, I know which ones I prefer.

With uplands, if they just stopped one thing the burning, it would make a tremendous difference. I like what Ben had written, but disagree about the New Forest, (an area I know well), I don’t think it’s a model we should be trying to copy. Ian summed it up very well when he wrote that places are “stuffed full with people”. The key I’ve found is you have to give nature room, this farm has been handed lock-stock and barrel to nature – it works, (RSPB, Wildlife Trust please note).

Cattle, wild ponies would be great on the moors, I’m not adverse to sheep, but these animals seem to be penned up more in confined areas, that’s not good. Planting of conifer plantations I’m against, planting of native conifers in a mixed open mosaic, I’m pretty much for.

I thought Chris Packham spoke very well the other day, when he hypothetically talked about what happens if Grouse Moors were ever to be banned and who would look after them? I thought somewhat that the owners might have a say with that. Most of the people, who read this blog, have no idea of the rewilding process, they read and follow people who equally have no idea either and their only rewiding experience extends to the planting of sweetpeas in their garden.

The unfortunate issue with rewilding is its used as a get out of jail free conservational remedy, any problem we encounter – rewild, a one size fits all solution, it’s not that simple.

James you’re right, and I hope this didn’t read as an attack on farmers, as you know I tend to rigorously separate farming practice and farmers – the former is often the issue and the legislation makes it very, very hard for good people to do the right thing. In some ways, your fencing plans would create something like eastern European rotational farming (scrub meets open, open meets weedy, weedy meets seedy, seedy meets grassy and so on) and I’d fully support that. Where possible, true commons grazing (no fences) is my favourite, but I can see that 250 years of history and enclosure can make this tricky. In any case, I look forward to coming up in August and seeing your farm. Ben

In that case can you please separate Clear-fell and Continuous Cover Forestry.

You can’t have an enlightened farmer, it is an oxymoron [like good cop], because you cannot have a good apple in a rotten barrel. Even ones that might want to be good have to exist in a system that is corrupt and punishes good ideas. A system that requires conformity. The only thing enlightened farmers can do is stop being farmers, same as the only thing good cops can do is stop being cops, otherwise they are just another cog in the same old bad system.

Wow – that’s a startling level of bigotry about a massively diverse group of people.

That’s me out of the conversation.

I profoundly disagree with this statement. Ben.

My previous comment wasn’t to have a dig… hopefully it isn’t heard that way.

I simply believe that we have grossly underestimated the ‘upland farmer’ reducing him or her to some kind of stereotype. They are no different from any other group of humans, and many of them are smart, interested in nature, and very open to persuasion and listening, and influencing and shifting to different land management.

In the Lake District probably the greatest landscape changes for centuries are currently taking place – over a million trees planted in the last five years, changes to rivers and wetlands, changes to grazing practices, and multiple experiments in regenerative farming and habitat restoration. Our little valley has a rewilding fell, rewiggled streams, abandoned, restored and newly created wetlands, lots of good natural flood management stuff, maybe a hundred thousand new trees, miles of new hedgerow, several cool projects restoring meadows and diverse pastures, etc etc – done by dozens of people, the focus on me isn’t accurate. It is still mostly farmed.

Is change happening…

Everywhere?

No.

Enough?

Probably not.

But is it getting better?

Yes. Radically and quickly.

The main game isn’t getting rid of farmers but helping them change over time.

The other thing about Ben’s take on rewilding is that it actively encourages predator and deer control (in the absence of natural large predators). I’m not really in to shooting or killing things, but it is a major part of what Ben is saying, and chimes with what many upland farmers believe is necessary. This realism is necessary to build bridges.

The days of this being a silly bun fight need to come to an end – we should be mostly on the same side fighting for massive landscape change and viable futures for rural communities. As Ben says, it doesn’t need to exclude good farming, just reinvent (or restore it) it in many places.

James – well it would be good to be on the same side as everyone else, but if we were all on the same side then all of this would already have happened. You don’t have many grouse moors in the Lake District do you? Many of us are happy to work with anyone who is heading for the changes that are necessary.

Not that I know of.

Grouse moors aren’t part of my upland experience at all.

My point isn’t that we are all on the same side but that we need to get way more of us to the agreeing bit in the middle.

I’m talking about how we do that.

With respect, you think that change happens by going at people quite aggressively if you think they are wrong (and playing to your own audience) and I think it is often a poor way of creating change.

Change always requires compromise and moderation and a willingness to respect the other.

I respect what you stand for and listen very carefully indeed, admit where you are right, and spend my life compromising.

James – don’t tell me what I think, please. I think that it depends who you are dealing with. I can deal with anyone who shows good faith. I can compromise too but not with those who don’t budge an inch – and I am thinking mostly of the grouse shooting bunch. You ought to read my book – I’ve read yours (several time).

Final comment:

There is a lot of talk about ‘reimagining the uplands’.

Most of which ignores the fact that this really means tens of thousands of small across of imagination rather than a bestselling book or a big theory.

We totally miss that landscapes are always being reimagined by the people in them – this is already happening and has been for some time, I could show you half a different reimaginings of the uplands that are turning real within five miles of my house.

A democratic version of reimagining landscapes would be more about trusting upland people and helping them to change.

James – where you and I differ a bit is that I see my taxes paying for the livelihoods of upland people so I reckon that the tapayer has a more active role than simply handing over the cheques and trusting. This is particularly so when many of us could add to the tale in your excellent book https://markavery.info/2015/04/12/sunday-book-review-shepherds-life-james-rebanks/ of your grandather telling you that the trick of dealing with the man from the ministry was to agree to everything and then carry on regardless.

That’s story is exactly what happens when we divide in to camps and one camp is subjected to rules or incentives from the other without buying in to the same agenda – you possibly haven’t understood the passage.

I don’t for one second think you should hand over your money and be handed a con – that’s not what I am saying. I’m saying you have every right to more and to a strong say in what your money delivers, and the only way to make this work is dialogue rather than grandstanding on both sides.

You say – “I could show you half a different (dozen) re-imaginings of the uplands that are turning real within five miles of my house.”

And that’s great, but where I am typing, for more than five miles in both directions the land is owned by a single absentee landlord with 2 tenant farmers. And therein lies the major problem. Without major land reform we will be grasping for crumbs for a long time yet.

I’d say the issue with my piece (holding my hand up here), is that it covers three very different outcomes. Upland farming is something that will reverse one farm at a time; James, your analogy of pieces of a jigsaw turning over is exactly how this will happen. Grouse moors are different; these are unfarmed areas with far less social, economic and cultural depth, as it were, but they are also ‘easier’ in regards to the ecology. In other words, if you look at the large estate owners, Glenfeshie etc shows that big estates can give us the wilderness, when they choose. Farms are different. I would like to see our upland farms give us the lost wooded mosaic we once had. This is not wilderness, nor people-free. It is a populated world, filled with both people and a staggering abundance of birds. I’ve seen this in many parts of eastern Europe and will continue to work with anyone to make this possible here. Perhaps 3 separate articles might have been better. Ben

Its frustrating how Continuous Cover Forestry (https://www.ccfg.org.uk) is never mentioned when it comes to plantations as it is the perfect half way house between biodiversity improvements and timber production.

As conservationists\environmentalists we need to learn about other methods of silviculture and support and push alternative silvicultural systems like we do with regenerative agriculture.

Henry, there are many excellent models out there, just they’re not entering the UK mainstream. Very happy to discuss further and thanks for sharing this very interesting link. Ben

I agree. CCF is suppressed by the large forestry pressure groups and as such it rarely gets publicity.

I think you’ll find in the coming years more interest from younger foresters. However, like the recent gains in regenerative agriculture it needs to be fostered and some what supported from pressure within its own industry.

If you are ever in Mid Wales, Wales I would be more than happy to show you some fantastic examples of Sitka Spruce in transformation to mixed species CCF.

You can’t bully or police people in to progressive landscape change… like my grandfather in that story they will mug you all day long.

The story isn’t meant to celebrate that, merely show it.

Better by far is to win them over to want change themselves.

James – is it only in farming that you are paying people to do things and then on top of that you have to persuade them to do what they have agreed to do in return for your money?

Mark – your understanding of what you are ‘paying for’ is really really poor.

We pay farmers about £130 billion a year to produce the cheapest food in history and in whatever way that takes. It does enormous damage. We then spend £3 billion trying to redress the damage done by that economy.

It is hopeless and bound to end in misspending and defeat.

I am not defending non compliance with agri-environmental schemes (I believe passionately in them and try and over deliver on my own) – I am trying (apparently with zero success) to explain that we need to change massive things that are way beyond subsidies or your ability to make happen by force against people’s wills.

I’m going to leave this here as people are will fully ignoring or misunderstanding my position – or are just plain daft – but I spoke here to try and shed some light on this. And am sadly leaving fairly convinced you don’t want to work with farmers, or talk to them, but actually like the culture war approach that has achieved so little.

This is just an echo chamber.

James – you get stroppy quite quickly. We don’t make any payments to farmers for food (except in the shops and only a small part of that goes to farmers). There is no link between single payments and food production they will be paid provided the land is in good condition for future farming. The system is regressive and props up inefficient farming, some of which is good for the environment and some of which isn’t. And then we do pay for environmental delivery (we rent these public goods because the schemes are time-limited and voluntary) and should expect delivery.

The stated aim of this government is a fairly good aim – to make the payments to farmers from the taxpayer solely for environmental goods and let the market do the rest. I’m quite keen on the former (but I bet the government won’t deliver a good scheme) and very nervous about the latter because it is difficult to see how the market delivers public goods with any reliability.

We do need to change things and we have massive power to do so if only government acts for the benefit of all.

I’m sorry you feel that way James. Whilst people have challenged you they have done so in a respectful way. There is no need really for the lack of respect shown in that last post.

See Random22

1 person who everyone ignored. Not exactly representative

James – how about writing a guest blog to put everyone right – or say whatever you want to say.

I think there is a real danger for farmers here James. Whilst in the EU payments to farmers were guaranteed, farmers could do what they like, not so now. If farmers are seen to be abusing the trust and not delivering what they are being paid for then the money will be taken away. Simple as that. I can see the press articles now. The idea that anyone is ‘bullying’ farmers is simply not true. No one forces farmers to accept the agri-environment money anymore than a builder is forced to accept a government contract to (say) build a house. But once that contract is signed it is not unreasonable for the person paying the money to expect delivery. Nor do I think it reasonable for the person delivering the contract to take the money and then start arguing about what bits they actually want to do.

Who in their right mind is arguing for non compliance?

No idea why you think that is what I arguing for.

Sorry James if I misinterpreted your comments. Perhaps you can explain a bit more. Neither of us yet know what the new agri-system will look like, but it is likely that there will be prescriptions that will need to be followed (or not). What exactly do you think the ‘discussion’ will revolve around?

I wasn’t referring to agri environmental schemes as bullying – I don’t think that

I was referring to the approach of trying to change landscapes by force without doing the hard miles of persuasion, education and trust building with communities

James – and who advocates that James?

Thanks for the clarification and sorry I misunderstood. I am still not entirely clear, may I ask another question? How is this change being ‘forced’ on people?

Well, I don’t feel qualified or confident in talking about what the uplands (mainly grouse moors) should become in an ideal world. Though I do know a lot about them in their current state, and their history. I am in favour of banning DGS. But one thing that always seems to me to be downplayed in “the new visions” is the issue of managing public access (not ecotourists, but just the general public) so that it is both fair and open to “us” the population at large, and yet can mitigate the genuine problems open access can bring to the natural world, managed or not. Perhaps I need to read the book.

The only other thing I would say is we should not look to Alaska, wider America or Canada for any inspiration as to how to conduct hunting. It is just as bad as ours*. An anecdote from one American hunter from Alaska is irrelevant, misleading and totally non-indicative of the horrendous wildlife killing welfare standards in the US. I mean, after all there are one or two (yes, literally one or two!) grouse moors and keepers that do do things legally and with moderation, yet we know this is totally untypical and not indicative of the wider industry, so we would treat an anecdote from them with healthy scepticism.

As examples, in the US they still use steel jawed gin-type traps quite legally for Raccoons, Coyotes, Bobcats, etc. Bowhunting and Crossbow hunting for large game such as Bears is very popular and incredibly cruel. Wild and feral Boar are shot by paying guests whooping and hollering with machine guns from helicopters. Their standards for bog-standard full-bore rifle deer shooting are way below ours. In Britain most deerstalking and deer control (esp by the FC) conforms to BDS minimum competency standards…i.e. we wouldn’t shoot multiple rounds Rambo style at a moving animal & we certainly wouldn’t shoot them up the arse as they run away…but American’s do it out of choice.

*In any case, there are hundreds, probably thousands, of American “sportsmen” that fly in for British driven game shooting (and some own our “best Estates”).

Also they do have their own driven shoots in the US, of reared Pheasants and Quail…inspired by us and run on similar lines.

In addition, scores of American sportsmen make seasonal trips to South America (mainly Argentina) and are happy to shoot flights of Doves in a similar style as our driven shooting and party’s of Guns bag upwards of 2000 birds per day.

I am sorry, maybe I am becoming anti-American…but I just don’t swallow any notion that their hunters know how to nurture and safeguard their flora and fauna any better than ours. I am as likely to listen to ye olde Alaskan hunter as I am to Old Joe the keeper talking bollocks about his love for Merlins.

I worked* for a short while for the US Fish and Wildlife Service on a National Wildlife Refuge in the early 90’s and some of things I witnessed were insane. Gun-toting packs of chaps tearing around in their 4x4s and getting into drunken quarrels, both with each other and with the refuge staff, who also had access to an armoury. Twice I saw the refuge staff come into the center (sic) and tool themselves up with barely suppressed glee. The first time was when a goose hunter was seen ‘skybusting’ (i.e. he shot a couple of sandhill cranes out of the sky for the heck of it) and then got aggressive when accosted. The second was even more bonkers. A hunter had bravely taken out some ground doves (almost not worth calling a dove they’re so tiny) but someone else’s dog had grabbed them and was in the process of taking them back to this other hunter. Incensed, he shot the dog. The dog’s owner then started shooting at him.

It was only one of very very many such NWR so I cannot claim that what I saw was universal. But, it doesn’t suggest the US hunting industry was then (and I’ll warrant, is now) a paragon of balance, common sense, sustainable harvesting of a well managed resource and general virtue, in case anyone thought it was.

*my job title was research ornithologist. I discovered the first pacific diver ever seen on the reserve and the first overwintering records for costas hummingbird and cassins kingbird, amongst a few other things. But there was little or no interest from the reserve staff in anything other than how many Canada geese I counted in my first job every morning and whether it was more than the next NWR along (so they could put a big number on their daily answerphone update, get more hunters in and get more revenue from hunting day passes…)

Dominic – interesting tale, thanks.

Nail on the head Spaghnum.

Yes I agree. There is an impression that some people believe that the UK is the only country in which shooting is associated with unacceptable practices. Birds of prey and other predators such as wolves are illegally killed in various countries including the US and various European countries (see the work of CABS). I recall an American hunter asserting to me that the correct thing to do with wolves was ‘Three S’ – shoot, shovel and shut-up, i.e. more or less how hen harriers are ‘dealt with’ on our moors. It would be nice to think that it was only here that wildlife had to cope with persecution by hunters but sadly the problem is much more widespread.

If you don’t think deer are ‘shot up the arse’ in the UK, take a look at this:

https://veterinaryrecord.bmj.com/content/152/16/497

Thanks for that link. If I am reading the abstract right it suggests that (in lay-mans terms) 15% of the Red Deer hinds studied succumbed to a single shot which damaged the cervical area. So it likely is as you say, they are doing it here as well. I can hardly believe it…that it not the deer shooting world that I was once involved in, and I am going to dig around with some folks I know who in the deer stalking world (albeit Roe Deer) for some extra information. If this has crept into become common practice it is an outrage and needs shouting about very loudly, so thanks again for letting me know. I have no problem with standing corrected, it is the truth that matters. Cheers.

I believe you have misinterpreted ‘cervical’, in this case it refers to the neck bones. A neck shot is favoured my some stalkers as it minimises meat damage from the bullet and when performed competently puts a beast on the ground instantly.

Shooting moving deer or deer ‘up the arse’ is just not part of UK deer Stalking culture and will always be frowned upon by other deer stalkers. Not only is it unacceptable on welfare groundS such shots have great potential will do a massive amount of carcasse damage, and venison money is an important income for both individual stalkers and sporting estates.

Thanks, I hope you are right. I would be quite upset if some of those horrible American ways had crept in. Years ago I was a BDS member myself and did the Level 1 course, when I was into stalking (Roe & Fallow) I always felt as a “sport” and method of control it had decent humane standards, way above game shooting. That said, I still wouldn’t do anything like that these days. Thanks for your information.

I think you may be having some bad luck when thinking

I find it curious and disappointing that in this whole blog only one human being is quoted and they are not a shepherd, a forester, a gamekeeper or any other resident of the UK’s uplands. But rather an Alaskan hunter.

We may not all have you breadth of international travel experience, but there is a profound depth of knowledge and connection with landscape in upland communities that deserves far more respect than you give it.

Matt – go on then, give as the benefit of your wisdom please. Would you like to write a guest blog?

No thanks

Matt, you really should. The centre-ground moderates (like yourself and Patrick Galbraith) have got to break away from blind allegiance to the top-end who are going to drive it all to oblivion. I’m speaking as an ex-shooting man, ex-BASC member and ex-Shooting Times reader. The raptor persecution thing cannot be hidden or brushed away anymore these days, what with sat tags and covert cameras.

The common sense working class (or at least not upper class) shooting man has got to stand for a better set of principles and break away now or lose the lot within a generation.

Why not write a blog? Some may give you a hard time without engaging with the issues, but they would be stupid to do so, and there are a few others on here (me among them) who know both sides (the good and the bad) and who will back you up when you are speaking the truth. Give it a go!

Go on, you know it make sense.

As an upland hill farmer, the practical application of wild cattle is that they can be dangerous to passers by. Especially those with little knowledge of how to behave around them. I have hill rights in to a small 2000acre hill, and I would be frightened of the consequences. Please can anyone tell me of the laws regarding people who are attacked by livestock?

Thing is Matt this ‘connection with landscape’ hasn’t done it or the public in general much good has it? Exposed and eroding peat haggs and lack of tree cover meaning water runs off far too quickly threatening proper farmland, businesses and homes downstream. People are effectively giving money to something that increases the chance their front rooms will turn into swimming pools. The farmers that deserve respect are the ones like those of Pontbren who took the initiative to do something different and better. They did, they integrated tree planting within their sheep farms which improved their productivity, economics and greatly reduced the rate at which water ‘escaped’ from their land. They have been rightly lauded for this, received several major awards and the Woodland Trust and no less than George Monbiot has praised them to the hilt. In my own modest way I’ve done my best to put them forward as a great example of what farmers can achieve – having had dealings with crofters I really appreciate those that don’t just take, take, take all the time. I even tried to email them a well done, but the address was duff.

So Matt why haven’t the NFU, NSA or any agricultural organisation promoted the Pontbren farmers to the public or other farmers? Why aren’t they patting them on the back rather than George Monbiot? Is it perhaps, and I say this expecting to be struck by lightning because hill farmers are holy and I’m committing heresy, they are people too and some, often too many want to get as much as possible for as little effort as possible even when they may have some moral obligation to those who are actually supporting them? Honest conversation is long overdue, so far there’s been far too much bullshite https://www.woodlandtrust.org.uk/media/4808/pontbren-project-sustainable-uplands-management.pdf

Matt,

My blogs are written for free, are short, and reflect a fraction of the detail in Rebirding – which, whilst far from perfect, was written over 4 years and has the detail you seek. I do not disrespect hunters or shooters (others may). I challenge the profoundly limited models that we embrace in the UK – and wonder why we cannot change them. Unlike some, I actually argue that the older hunting models of ‘wildland protection’ might benefit us all.

Some shooters, hunters and foresters ask me why I do not quote more people. This is a fair question. My reason is that anyone can explain anything; words do not alter reality. There are 100 arguments for spruce crops. Yet still, these are silent deserts. There are fine arguments for driven grouse moors. Yet still, the harriers and eagles are absent, as are the trees and often, even the quarry species like black grouse. I’ve read the explanations for years. But I have also visited the places for myself.

In my view, the biggest issue with the dialogue is that everyone tries to justify decisions made in the past. Sometimes, foresters, gamekeepers, and yes, conservationists, have spent lifetimes failing to prop up their models. It isn’t fun to realise such long-term projects have failed.

I agree my international experience is a privilege. I try and make that count by sharing the lessons I’ve learned in writing. Whether these are taken up, however, is really beyond my tiny sphere of influence.

Ben

Rather sad about the falling out.

Read through all the comments twice and not sure why when the intentions appeared broadly shared. Surely different ways of achieving better futures, depending on landscape, land use and resources.

But two points – the first about grants. All will change with Brexit, but there will still be grants from various sources. And grants steer choices affecting land use, flood management, hedges – uprooting/planting, maintenance of walls etc and farming practice.

The other is about simplification of issues and how that is affected by ‘personality media’. Any television country/farming/nature type programme has to be fronted by a well known ‘personality’. They tend to interview other ‘personalities’, who, even if they came to fame through researching/writing get just a sound bite or two. The level of information and discussion seems geared to the younger end of primary school with an attention span of three minutes.

Note for instance the recent Countryfile, tuned into because of interest in the Stiperstones/Long Mynd project: a positive example of farming with conservation. But so many reiterations of generalities and zilch depth, with as ever, the personalities standing in front of what we want to see.

Sorry if this is becoming a rant, but guess readers of this blog might be similarly annoyed.

Wildlife magazines too – thin articles.

There seems little middle ground between the ‘sweet pea grower’ who has read a best seller on ‘rewilding’ and the incredibly knowledgeable and experienced.

So I guess I’m asking for a media/publication middle ground, in which the interested ‘sweet pea grower’ is able to find out much more, to influence/spread the word, not worry about meeting cattle in the uplands etc……. whilst not committing to becoming an ‘expert’.

“There seems little middle ground between the ‘sweet pea grower’ who has read a best seller on ‘rewilding’ and the incredibly knowledgeable and experienced”

These are not mutually exclusive.

I would be greatly distressed if the incredibly knowledgeable and experienced were unaware of the simple pleasure of a fragrant vaise varse or vause of flars

It’s something I find myself thinking about a lot, living near the North York Moors. On the subject of tree cover, you often see birch, rowan and oak clinging to steep moorland slopes and crags, basically the only areas that avoid heather burning and sheep grazing (rabbits likely impacting too in places). I can think of many places on the NYMs like this, thin strips and islands of trees on steep ground, including the brows of the high moor tops at the 300m mark, sometimes a bit higher.

I don’t see why those couldn’t be utilised to create (naturally regenerating) upland native woodland on the moor edges and streams, creating more variety of habitat without even really infringing on the main heather moorland at all. And could well be compatible with less intensive forms of shooting.

Appreciate that Ben wants to sell his book, and that Mark wants to drive traffic to his website but this blog would have benefited from some basic fact checking.

1 – “The first model proposed (in no particular order), is blanket single-species forestry.”

1.1 – No one has planted blanket single-species forestry in England for circa 30 years. New forestry planting is regulated by the UK forestry standard – UKFS can be downloaded here https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-uk-forestry-standard

1.2 Despite all the recent talk of tree planting from all the political parties, only 2,300 Hectares was planted in England over the last 12 months – only 10% of that was conifers – https://www.forestresearch.gov.uk/tools-and-resources/statistics/statistics-by-topic/woodland-statistics/

1.3 Modern forestry plantations are not “blanket single species” – Doddington is a good example of recent planting in the north of England – planting design can be seen here

http://www.doddingtonnorthforest.com/planting-plan

2. “Several forestry papers exist to show that these forest environments can support some life.”

2.1 The paper are quite clear about what life they support and its slightly more then Ben states – https://www.forestresearch.gov.uk/documents/6989/fcrp004.pdf

2.2 This “Lost Peatlands” presentation by Dr Hipkin from Swansea University also clarifies the range of biodiversity in conifer plantations in the S Wales valleys https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=g1hD-0nezrw

2.3 Ben also thinks that conifer plantations are silent – they aren’t https://twitter.com/TilhillForestry/status/1265545347704803332?s=20

3.0 “So in the ongoing search for common ground, replacing spruce forestry with birch & pine forestry,”

3.1 Birch, pine and spruce have very different fibre and timber properties. https://www.forestresearch.gov.uk/documents/1439/FCRN026.pdf

3.2 They also require different soil and climate conditions – https://www.forestresearch.gov.uk/tools-and-resources/ecological-site-classification-decision-support-system-esc-dss/

3.3 Spruce grows 2-3 times faster than Pine – so in simple terms we would need 2-3 times the land area managed as commercial forestry, to produce the same amount of timber/fibre .

4.0 “Yet the most interesting fallacy of all is that we need spruce at all.”

4.1 The UK imports about £8 billion worth of forest products every year. We offshore circa 80% of our forest product footprint – https://www.forestresearch.gov.uk/tools-and-resources/statistics/statistics-by-topic/timber-statistics/uk-wood-production-and-trade-provisional-figures/

4.2 If we just look at 1 product – sawn timber – UK imports 0.5 million tonnes of hard wood (including Oak & all tropical timbers) and 7 million of softwood/coniferous timber. Much of the latter will be Norway Spruce. https://www.forestresearch.gov.uk/tools-and-resources/statistics/forestry-statistics/forestry-statistics-2019/trade/apparent-consumption-of-wood-in-the-uk/

4.3 We also use Spruce fibre in the UK to make high quality “Folding Box Paper Board” at a large mill in Workington https://www.iggesund.com/about/global-presence/the-workington-mill/ – Spruce fibre is used becasue it is white and because the fibres are long & reasonably strong.

5.0 “whilst creating arguments that really, deep down, birds love a bit of single-species monoculture.” – Perhaps Ben or Mark can share some recent evidence of these arguments ?

6.0 “And this is a vision that doesn’t preclude ecotourists or hunters, foresters or farmers.” – Foresters seem to have been excluded from the illustration at the top of this blog.

I’ve exchanged emails with Ben and have invited him to visit some modern forestry plantations, once we are completely clear of the Corona virus restrictions.

That offer still stands, but i am frustrated and annoyed that Ben and Mark are more interested in book sales and website clicks, than an informed discussion about upland land management.

Hi Andrew, blogs are brief matters but the details of blanket spruce/conifer/other ratios are all addressed in Rebirding’s chapter “New Forests”. As a seasoned forestry professional, I understand you may not wish to buy the book and therefore will post you a copy free of charge. Please let me know your address. Best, Ben

Thanks for the offer Ben. As mentioned in our email exchange, i’ve already read your book. Your blog contains a number of inaccurate and misleading statements. If you are interested in constructive dialogue with forestry professionals, I would recommend that you take a little more care when making public statements about forestry.