Lee Schofield is senior site manager at RSPB Haweswater, where partnership work with landowner United Utilities is aiming to find a balance between large-scale ecological restoration and hill farming in the Lake District National Park. He is also a nature writer, working on his first book which will be published by Penguin/Transworld in 2022. Follow him on Twitter: @leeinthelakes

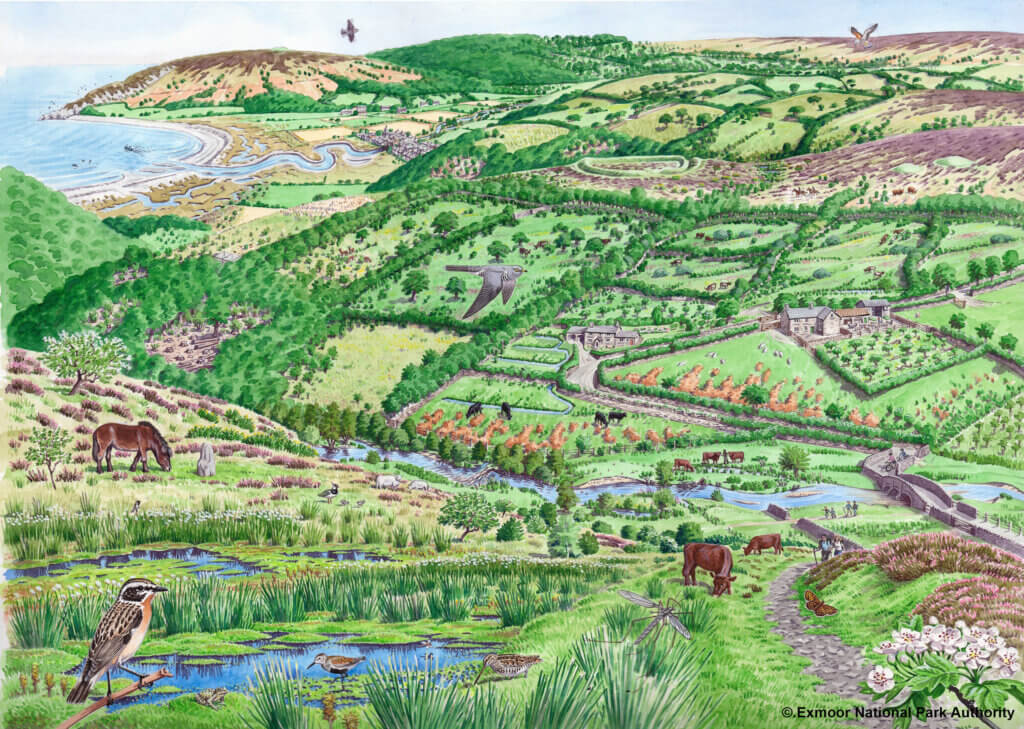

Last week a beautiful new illustration of Exmoor National Park was unveiled. The work of Norfolk-based wildlife artist Richard Allen, it depicts the rolling landscape around Porlock Bay on the rugged Somerset coast. Burgeoning hedges and scrubby woodland full of wildlife break up a patchwork of valley bottom fields, encircled by heather-clad hills lightly grazed by cattle, ponies and sheep. Busy with people working and enjoying themselves, it is every bit the bucolic, rural idyll that the countryside inside a national park should be. But this is no ordinary illustration – it wasn’t drawn from life. It is instead a rendering of a possible future, commissioned by the Exmoor National Park Authority to help people picture a landscape where nature has been reinvigorated.

Though less visually appealing, the report that accompanies the illustration is no less stirring. In its 24 pages, it explains how desperately nature is struggling, even inside the boundaries of national parks and other protected areas. It makes an incontrovertible case for change to address both the biodiversity and climate crises that we’re all facing and describes how a nature rich future could be brought into being.

As the site manager at RSPB Haweswater, a large upland nature reserve in the Lake District National Park, I find Exmoor’s vision ecologically credible and thoroughly inspiring. Richard’s illustration depicts many of the habitats and species that we’re also working to restore on our land.

I wasn’t the only one to find it so uplifting. The vision received the thumbs up from nature enthusiasts for its clear, uplifting portrayal of the future; such a departure from the ecological doom and gloom we’re all used to. However, not everyone was so enthralled.

Articles in the Mail and the Telegraph appeared quoting an Exmoor farmer who claimed that realising the vision would turn the national park into a ‘rich boys’ playground’. Others worried that the landscape that was being presented didn’t have enough farming in it, reducing our nation’s ability to feed itself and impacting livelihoods.

A more dramatic manifestation of this same narrative occurred last year, when the charity Rewilding Britain was forced to pull out of a landscape scale nature recovery project it had initiated in Wales because of pressure from disgruntled farming groups. Their primary complaint was that they were having changes imposed upon them rather than being part of the design and planning process.

Part of the problem stems from how grand the ambitions of these projects are. The Exmoor illustration shows land extending to well over a thousand hectares; land owned and worked by many different people. Even though the national park authority worked hard to engage, they can’t possibly have spoken to everyone with a stake in the scene. How would you feel if someone presented a design for how you should look after your garden, without coming to talk to you first? Formulating a vision for the land of others is always going to be inflammatory. But how else to communicate what change might look like?

Some of the concern is down to the R word. Even though the term doesn’t appear anywhere in the Exmoor vision document, detractors were quick to brand the vision as ‘Rewilding’. It’s true, it includes an ambition for 10% of the National Park to be a place “where nature and natural processes are allowed to take their course.” Beavers, pine martens and red squirrels are mentioned as species that might recolonise. This sounds a lot like rewilding to me.

Rewilding is a word that seems to be able to enflame passions on all sides of the debate about the care of our countryside. To some people it means hope for a better future for our wildlife, trusting that nature can repair herself when given more freedom. To others, it speaks of land clearance, the sweeping aside of traditions and the imposition of a liberal elite agenda that excludes farmers and their families.

Like it or loathe it, rewilding is gaining traction. Last week Rewilding Britain launched the website for their rewilding network. With 17 sites totalling over 200,000 acres of land, it’s an impressive start. What marks these projects out as being distinct from the land in Exmoor’s vision, is that they are virtually all happening on large estates, owned by individuals, government agencies or NGOs. No surprise that Rewilding is seen as a something for the ‘rich boys.’

Rewilding is busily shaking up the world of nature conservation, forcing a fresh look at practices which, while having been successful at saving species and improving habitats here and there, are not keeping pace with catastrophic wildlife losses. To conservationists like me, this is a stark and sobering truth. Rewilding isn’t a silver bullet, but it is undoubtedly part of a multifaceted solution to the wickedly complex problem of biodiversity decline.

Farming is currently undergoing its own comparable revolution. Regenerative agriculture, a style of farming that focuses on the health of the soil is also gaining ground, quite literally. By employing pulses of grazing, mimicking roving herds of wild herbivores, farming innovators are building up their soils, reducing their reliance on chemical inputs, locking up more carbon, and leaving more space for flowers, insects and birds. Like rewilding, it’s bold, innovative and exciting and could well prove a valuable part of the solution to our global woes. Unlike rewilding, it doesn’t piss farmers off.

The Exmoor vision hopes to inspire an even larger area of regenerative farming as it does of rewilding. In truth, it will probably be hard to draw lines between them. Rewilding often uses hardy native breeds of livestock to simulate natural grazing patterns. Regenerative agriculture does that too. Regenerative agriculture claims to be able to reduce flood risk, mitigate climate change and boost biodiversity. So does rewilding. Both are at the cutting edge of their respective fields, being practiced by innovative people, passionate about doing their bit for the natural world.

Is it surprising that the vision for Exmoor upset a few people? Not at all – change is always difficult. Is it likely that we’re going to stop arguing about the best ways to care for our countryside? Not very. Is it time to stop quibbling about what different approaches are called and get on with the urgent task of breathing more life back into our land? Undoubtedly.

[registration_form]

Whist I find it difficult to disagree with the sentiment of Lee’s blog let’s not get carried way.

Firstly – the Exmoor document is a vision not a delivery plan (I’ve seen more visions over the years than I see Skylarks locally).

Secondly – it is yet to be adopted by the NP.

Thirdly – it is woefully weasel worded aiming for 75% “nature rich” by 2050. Well that means one thing to a sheep farmer (who probably thinks it’s nature rich already) and something quite different to most readers of this blog.

Fourthly – unless and until there are changes to the purpose, duties and governance of NPs (as per the Glover review) and more ££ this will remain a vision. There was a good Twitter thread from Kate Keasden (also of RSPB) on this a few days ago. https://twitter.com/KeasdenKate

Finally – ELMS the major mechanism for actually delivering all of this is not even due to begin roll-out until late 2024 and according to Defra not due to be “tried and tested” until late 2030.

This probably sounds more grumpy than intended but it’s Monday. I’d get out more but it’s about to rain – again.

Tim – yes but it is a good start, and if every NP in the UK had something similar then we would start to see more progress.

Actually I think it’s rather a poor start (although clearly it is a start of sorts). Where in the vision is there a vision for society valuing all of this in terms of extra money? Where in the vision is there a vision for Gov’t valuing all of this through a change in the NP’s purpose and duties? It could have been much better.

As you can tell I’m still grumpy and now it is raining!

Hope it’s stopped raining. Clearly there is a lot more to do, but a start of some sort is better than none. It shows a lot more ambition than some national park authorities.

A brilliant and achievable vision !

!5 years ago the then Exmoor National park officer told me that the average Exmoor hill farm got £30,000 pa in subsidy. Did any of them take that much home as profit ? I don’t think so. As I said a couple of days ago, the money is already there. In fact farmers might take home more if they farmed less. Food Security is a smokescreen for which I have no sympathy – what really matters to farmers, surprise, surprise, is farm income. That I do care about – and if farmers are persuaded they won’t lose out they can do almost anything.

On the food security, even if you believe in it the Less Favoured Areas produce just 5% of our food. Speaking for myself, 5% less food would probably do me more good than harm. On top of that the UK imports almost exactly the same value of lamb as it exports.

During foot and mouth, sitting in a pub, the current and former National Park Officers for Dartmoor told me that what was really hurting the farming community – far more than not being able to sell livestock – was the absence of visitors. In the male-dominated culture of upland farming the on farm B&B was seen culturally as the woman’s little business on the side – but the reality was that it was a crucial support to the barely viable ‘official’ sheep farming business of the farm.

Interesting point about the B&Bs. Several studies of marginal farm businesses have shown that second incomes, like B&Bs, or other off farm work are vital to keep farms going. This is probably how small hill farms have always had to manage, being just one activity in a diverse rural economy. The concept of hill farming as a full time occupation is a modern invention brought into being by post war subsidies. Worth having a read of the Less is More report, by Nethergill Associates, if you haven’t done so already.

I’ve noticed that farmers’ objections to interference from outsiders doesn’t extend to not taking their money in the form of agricultural subsidy. Funny that. Considering their concern about keeping the nation food secure (bless!) they never mention food waste or some of their colleagues being allowed to sell off better quality land to developers. If I were a cynical person rather than the Pollyanna I truly am I might think the real issue is maximum money for farmers rather than sustenance for the people. I also find it perplexing that financial support to preserve a traditional way of life somehow encompasses quad bikes, steel sheds, anti biotic treatments for sheep and sky sports.

If beavers are not permitted on Exmoor, as with any other upland area, that means more homes, businesses and farms downstream unnecessarily under higher flood risk. Isn’t it about time we worry about the people affected rather than a grumbling bunch of subsidy graspers that want to have their cake and eat it and everybody and everything else can just GTF? When the Vincent Wildlife Trust did all the stakeholder stuff re bringing back pine martens to Wales they recorded a few comments from members of the local community. The videos involving the attitude of sheep farmers were jaw dropping in their raw ignorance and selfishness – didn’t bode well for Rewilding Britain’s plans for the Summit to Sea project as has been borne out. Is it sacrilege to suggest it might be the farming community that’s actually at fault? Best of luck Lee you deserve it.

Absolutely Les, I couldn’t agree more. Sadly, from my experience in the Northern English and Scottish uplands, the majority of (upland; I have no experience of lowland) farmers believe it is their ‘god-given right’ to receive (public) money for being a farmer. Furthermore, a significant proportion don’t seem to believe that the regulations associated with receiving public money or legislation applies to them.

Thanks Les. In a slightly more optimistic spin, while there are certainly some farmer with the sorts of views you describe, in my experience they are a vocal minority. There is without doubt a growing number of more progressively minded farmers out there, often quietly getting on with doing what they can for nature, alongside their farming. Think we need to do what we can to support that section of the farming community in the hope that their numbers will continue to grow. Not saying we shouldn’t also call out the bad, but we need to recognise that there is huge diversity of views and approaches among farmers, and we should try not to lump everyone into the same box. All that does is increase the sense of tribalism.

I lived & worked on Exmoor for a couple of years, sat on the Park Authority for 7 years, and engaged in lots of farming and the environment activities. Its experience, very mixed, with all sorts of people engaged, has characterized a lot of the last 30 years of failed nature conservation effort across England. This said in the last few years I was there I also sensed a real appetite for doing much better A kind of ecological localism trying to escape the failings of the modern state and prepared to unleash innovation on its own terms. The interesting role for the Park Authority (& the myriad other agencies) is to enable options and possibilities for farmers land owners and others in creating a sort of ecological innovation District. Where land and the people associated with it become the ‘lively capital’ of a better future.

Mark Robins

Sounds like a future worth striving for to me.

For all the claims of independence, sheep farmers are as much state employees as I was working for the Forestry Commission.

But one thing I learnt over years of dealing with forestry policy & grants is not to listen to the rhetoric, only the results – farmers would protest violently in public about change then rush home to fill in the forms for the new grants.

In conservation terms the most extreme example was the Somerset Levels where NCC staff were burnt in effigy when they opposed lowering the water level so grassland could be converted to arable. It didn’t work – the soil was too poor. 20 years later, with no fanfare, farmers were sneaking in to ask NE whether their land could become SSSI so as to guarantee getting higher rate stewardship payments.

And I’me perhaps undervaluing the benefits in suggesting they needn’t cost any more – as Les points out, there are also huge money-saving benefits in terms of flooding – and don’t forget that the famous Porlock disaster didn’t just cost the insurance companies – it killed lots of people, possibly a warning of the shape of things to come if we continue not to take natural flood prevention seriously.

Do try to get your facts straight before committing yourself to airing your views publicly. There was no ‘Porlock disaster’: it was at Lynmouth – only 11 miles away so presumably near enough for some people. Thirty seven deaths, just as a reminder….

Totally agree with Les. As a person who has ived in the Lake District surrounded by woolly maggots (sheep) and public money graspers (farmers) for 50 years I couldn’t have put it better myself!

Oh come on if Red Squirrels and Pine Martin’s were likely to be happy in Exmoor they would already be there. I could not imagine the average farmer giving a toss about them being residents. Rather the opposite.

Fact is there are considerable numbers of Deer and Feral Goats there that do far more damage than even Beavers are likely to do.

My guess is that if anyone relies on Beavers to stop any flooding disaster on Exmoor they are seriously deluding themselves, as usual the part played by Beavers in flood prevention is enormously exaggerated by those with reason to do so.

Goodness I never thought rewilding would ever be as simple as Reds, Martins and Beavers, is this a joke. Bring it on LOL.

Well it is a bit of a cheek when someone with a reason such as writing a book coming from Haweswater RSPB which is in a area with far more problems than Exmoor which in actual fact is visited by lots of people for the variety of its nature tells us southerners what he thinks we should do.

Dennis – you’re pretty grumpy today. Where were you born?

Hi Dennis. Your comment made me laugh. I grew up in Devon and am forever being accused of being a Southerner for daring to live and work in Cumbria.

Not quite sure how my article is telling anybody what to do. And belive me, I’m very aware of the many issues in the Lakes and at Haweswater.

Mark. Well I am a proud Huntingdonshire person until pillocks did away with my county for no good reason and in fact as usual improvements actually often mean things are worse in future.

HCC paid for me to go to agricultural college for two years that otherwise would have never happened and I doubt the present county boundaries would not be so generous.

We have now lived for 55 years close enough to Exmoor to visit often and if your blogger and other commenters want to learn of Exmoor qualities for nature then they only need to look up about Johnny Kingdom.

If your blogger was really interested in Exmoor he would realise it really is already rewilded even if it has not needed the RSPB to put their twopeneth in.

I think Hawswater is in Cumbria and cannot imagine that your blogger would go on about Exmoor when I would have thought he could take lessons from Exmoor.

I wonder if a lot of opposition to rewilding is the result of people not understanding what it means (if indeed it has a commonly agreed on definition). Maybe a lot of people think rewilding means no human activity in a given area, plus the reintroduction of large carnivores etc. so when they attack the idea the are in fact attacking a straw man. Yes in it’s purest form rewilding means no human interference, large carnivores etc. but it can also mean many other things. I can’t remember where I read this definition but I think it should be widely adopted:-

Every area should be graded on a scale of 0-10 on the basis of how much life it supports and how “natural” it is. 0 would be a city centre with no wildlife and 10 would be untouched wilderness. Where ever an area ranks on this scale it should be possible for that area to move 1 or more places up the scale and this is rewilding. Under this definition rewilding doesn’t have to mean all human activity stops, and indeed regenerative agriculture is a form of rewilding if a farm moves from level 3 to level 4 because it supports more wildlife. For this idea to work conservationists would have to accept that there are limits (different in different parts of the country) as to how far up the scale each area can realistically be expected to progress, e.g. it probably isn’t possible to ever recreate level 10 in the U.K. and most of the country may never get beyond say level 5 or 6, but this is a big improvement if most areas are currently level 3 or lower. Under this system even our towns can be rewilded if there are more green spaces and they move from level 1 to level 2, and I think far fewer people would see rewilding as a threat to farming or their way of life.

Agree that the term rewilding being misinterpreted is a big part of the problem. Views about what it means, correctly or otherwise, are now so firmly entrenched that I feel that using it often does more harm than good.

At long last someone writing sense on rewilding.

None of you have the foggiest idea what’s involved when you rewild the landscape.

You all fall in line to the PR bollocks that’s pushed out to create jobs and wealth. Rewinding will never be the one jab vaccine that will solve our wildlife problems – and that’s from someone who’s doing it!

Thomas – where are you doing it – you never say, do you..?

This all seems to be between farmers and NP….what about the rest of us who want to live, work and produce on Exmoor, you forget about industry and creativity that Exmoor in so good at inspiring.

I feel that our pottery is a very important part of Exmoor , housed in a historic and important building , we have a river behind us that could power our kilns and pugmills but we would never get any kind of backing or help as it would go against any rewilding project !

Charlotte – thanks for your first comment here.

Are conservationists misleading us deliberately, let’s ask a few questions.

Does anyone seriously think that Beavers would stop floods such as caused such damage at Lynmouth.

Are we expected to believe that the Martin’s are a help to Red Squirrels by killing the Grey’s and not able to catch Reds, really are we supposed to think Martin’s not smart enough to raid the Reds dreys and take the young.

We were told in no uncertain terms that dredging the Somerset levels would not work and could make things worse. Well what do you know here we are with serious flooding in lots of places in 2019 but where Somerset levels were dredged just about the one place with no serious flooding.

It makes me wonder if conservationist need to exagerate things to try and prove whatever agenda they are pushing.

Well after investigating there are already Pine Martin in Devon.

Not that I am against them but if you introduce them they will inevitably take some of the birds eggs and chicks so it is not all gain and of course a waste of time introducing Red Squirrels unless you are willing to clear out the Grey’s and stop them re-entering.

It is a serious farce.