This is a very good book. It will be one of the books of the year for those interested in wildlife and wildlife conservation – perhaps THE book of the year. And that’s because it is very well-written, pretty important and deals with what is a largely novel subject to most potential readers. I recommend that you read it.

Traffication is about the impact of road traffic on wildlife and makes the case very well that the collected impacts of collisions between soft wildlife and hard vehicles, habitat loss and fragmentation, noise, light, disturbance and localised pollution add up to a bigger overall impact than is often (almost ever) acknowledged, and that it is so important that we ought to do something about it.

Why have all these impacts been low profile for so long? It’s partly because other factors, agricultural intensification, habitat loss and climate change for example have been higher profile, and so they almost certainly should have been and should be. But another reason is that the evidence has not been brought together in a rigorous yet understandable way until now. That makes this an important book as well as interesting one.

I know the author, we were colleagues at the RSPB for many years, and I rate him highly as a fine scientist and a good bloke, but when he told me that he was writing a book bigging up the importance of these impacts (not the exact phrase he used) I told him that since he was a bright guy I looked forward to it very much but it sounded like a stiff task to me. Well, I was right, it was a stiff task, but Paul Donald carries it off brilliantly. I’m convinced to an extent that I was not expecting.

Let us be clear, this book does not make the case that we should ignore agriculture, climate change etc but it does, very convincingly make the case for more attention to be paid to traffication and for more research into both impacts and measures to reduce those impacts. Understandably, there are many more studies which have demonstrated agricultural practices which do harm to wildlife and alternative practices that will reduce that harm than there are, at the moment, for traffication. Knowing that mowing kills Corncrakes (and other wildlife) in hayfields led to developing of Corncrake-friendly mowing which, backed up by grants to crofters, contributed to Corncrake recovery. Research, much of it by Paul Donald, on Skylarks established low breeding success in wheat crops late in the season, and led to Skylark patches being brought in and shown to work (though their uptake by farmers is poor). What are or will be the equivalents for traffic impacts?

As with most books about terrible things happening to wildlife, this book is better at describing the problem (and we should be very grateful that this book does that so well) than sketching out solutions. But there are more solutions, described here, than you might think. Having coined the phrase traffication, we now need to have practical measures to achieve a fair amount of detraffication. Maybe partial de-roading of some national parks might be a step forward? More traffic calming in rural areas, as vehicle speed is critical in impacts (actual physical impacts and biological impacts)? Maybe all private cars should have tachographs linked to GPSs which score their use of roads by wildlife and climate friendliness and those scores determine the price you pay for fuel the next time you fill up at the pump?

The author seems very optimistic that change can come, and that it can come fairly quickly. Maybe, but our inability, as a society, and in other countries, to solve problems such as overfishing, habitat loss and greenhouse gas emissions once the problems have been clearly identified makes me less optimistic that great change will come quickly. The road forward does not look smooth to me.

I was driving in the Northants countryside the other day when I stopped at a T-junction. I could see, as I approached, a male Pied Wagtail scurrying about on my side of the road. The wagtail moved to the other side of the road as I slowed down and when I stopped it was running about on my right, still pecking at tiny insects just a few feet away. It had, it seemed, spotted I was coming and taken rather minimal but completely effective evasive action to carry on with its life. Because I was most of the way through reading Traffication at the time I was more sensitised to this passing event than I otherwise might have been. He was a very beautiful Pied Wagtail and it was one of those brief moments of seeing wildlife that brings happiness into our lives – I’m very glad he wasn’t squidged on the road by me or anyone else. After watching him for a few moments, and then looking left and right, I turned right and in my mirrors saw him move back on to what had just been my side of the road and carry on feeding.

This book is very engagingly written – it is written with humour and culture and clarity, and that makes a huge difference to how receptive the reader is to the messages. The early chapters about the rise of the car and of increasing traffication might have been awfully dull in another author’s hands but are great reads here. I was captivated by the tales of early studies of roadkill, mostly those in the USA, starting on 13 June 1924 in Iowa City. Throughout, this book is an excellent read.

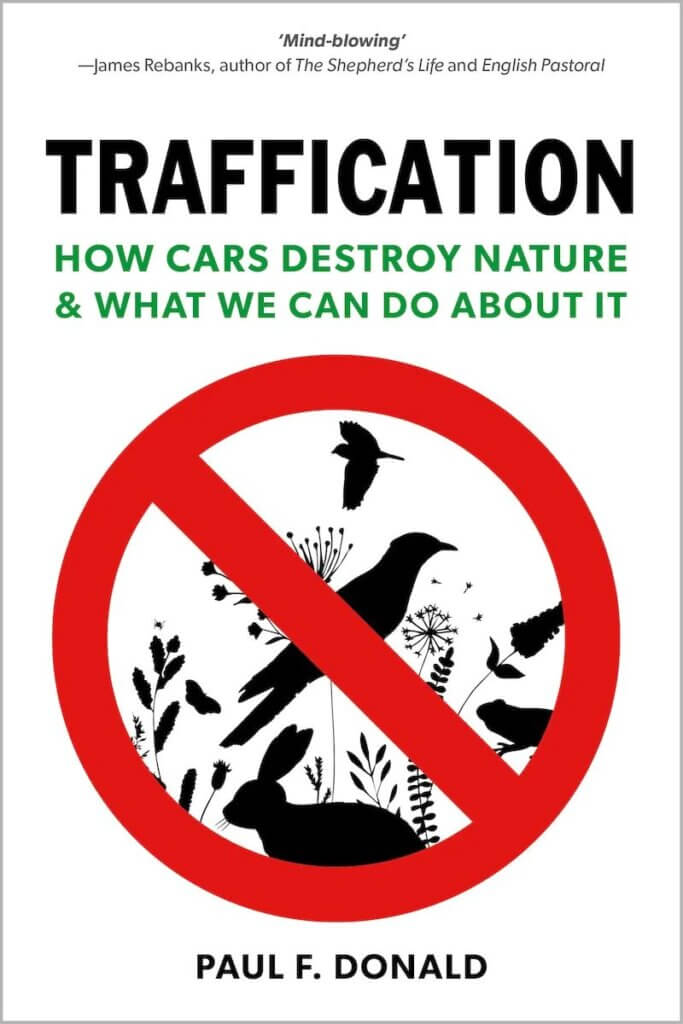

The cover? Striking and quite clever, although it’s odd that it contains an advert for another author’s two books after a one-word endorsement of this one. I’d give it 8/10.

Traffication: how cars destroy nature and what we can do about it by Paul Donald is published by Pelagic.

Buy direct from Blackwell’s – a proper bookshop (and I’ll get a little bit of money from them)

[registration_form]

A few weeks ago I was down in the Scottish borders at Innerleithen at Traquair House and was amazed at the amount of lichen I saw growing on some apple trees. The area is much too dry to be in the Atlantic rainforest zone, the reason for the staggering amount of epiphytes was the air was clean compared to what most of us usually breath in. A massive amount of biomass must be missing from our trees and woodlands due to air pollution destroying most lichen species, reducing it would allow it to come back and is therefore a form of rewilding.

Much of that pollution must be coming from cars – to make matters worse people don’t just have cars for convenience/necessity, but as a status symbol so that a significant proportion of the crap that kills lichen AND burns our lungs, especially children’s, is just there because of Chelsea Tractor vanity https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jN7mSXMruEo&t=22s. The conflict isn’t between people and conservation, it’s between conservation and public health against dicks quite frankly. This is so often the case as with grouse moors, conservation only clashes with the bad side of humanity that none of us are supposed to want – utter selfishness.

The execrable GB News has been predictably hosting car driving opponents of Low Emission Zones who claim their freedom is under assault – the freedom of children not having to breath in bad air is somehow not relevant. I really, really wish the conservation sector and the rest of us would verbally lay in to these creeps with the honesty and anger they deserve, they shouldn’t be accommodated by allowing danger to public health being swept under the carpet. I’m planning a future blog about the implications of the ‘Traquair Lichens’, there’s a big story there I never realised until I saw them. Looks like a fantastic book.

Well done Paul Donald. Cars etc are indeed a nightmare for nature as those fools who approve of formula 1 (which glorifies driving and cars of course) should realise and stop. Being in the southern uplands of Scotland and being able to hear whining hideous motorbikes from over a mile away, as they treat the world as their racetrack, shows how appalling this is. (And I don’t just mean actual races of course.)

But conservation organisations and filmmakers aren’t faultless either, far from it. The number of times I’ve seen reserve managers just thoughtlessly climb in their big diesel 4X4 and drive over the wild land they are supposed to care about I can’t tell you. And no, they don’t always have heavy tools to carry, they’ve just being the same as the rest of the world: taking the quick, easy option. And they’re the ones who are supposed to care about nature! Does RSPB and others have a policy on this? *How about setting an example?* And the wildlife presenters rolling along in their cars is so common in films it’s a cliche, an appalling hypocritical one.

The world is going to look back like we do to bear and bull baiting and say ‘how could they be so blind? how could they be so vicious and destructive?’ And they’ll be right.

Excellent stuff! Brilliant idea if conservation organisations had a policy of minimising car use and using vehicles no bigger than they had to that would be a start. Sadly some people have trouble enjoying life without straddling an internal combustion engine. Jet skis are a massive pain in the arse and I believe even in Yellowstone National Park a lot of the wildlife gets hassled by people on snowmobiles, then there’s the deserts and dune systems hammered by buggies. I’m with you, I can’t understand any joy at all in car racing, most especially Formula 1.

It’s good to know there’s a few sane members of the population.

Looking forward (if that’s the right phrase) to reading this after beginning with other books talking about car dependency and the human costs. As well as reading Traffication, I’d definitely recommend other books which will compliment it like “Movement – how to take back our streets and transform our lives” – gets you questioning our approach to travel. Paul’s right that most journeys don’t even need a car and that’s what we should all be thinking about & doing as much as possible, as well as the systematic changes/improvements needed to reduce car use (safe cycle routes etc)

Amy – thank you for what appears to be your first comment here.

Fighting Traffic

Once There Were Greenfields

Walkable Cities

Probably the most hard hitting engaging books I’ve read on the topic, better than the more discussed ones.

I have always believed that the internal combustion engine was one of man’s worst inventions. But I was born pre-Beeching when most villages had a station and if not, a bus was available for the weekly shopping trip. I am not keen on the jet engine for that matter promoting, as it does, mass movement but… hypocrite that I am, of course I use both. Most of us sixties students spent summers inter-railing round Europe. But if I could go back in time I would ride my old horse to visit friends, no drink driving penalties! In fact the past is eternally rosey. If given the option the only thing I would take with me into the past is modern medicine to which I owe my life.

Yes, the car is a menace to man and wildlife in equal measures but increased populations and the need for cheap food without seasonal fare forces us into its arms. Buy local, eat seasonal and avoid all food air miles, particularly soya and palm oil (sorry veggies). Then you can rightly be smug. Sadly I cannot claim this. It is a fantasy!

Sorry to diverge from traffic to a certain extent and I will read the above book. My nearest public transport is 4 miles away. I already minimise my usage of a car and try to drive carefully where wildlife (and people) are concerned. One paragraph here shows another problem which doesn’t get the attention it deserves.

“In the United Kingdom, official government data released in 2023 showed that more particle pollution comes from residential wood burning (21%) than from traffic (13%). The government analysis noted that PM2.5 emissions from residential wood burning increased by 124% between 2011 and 2021.”

From:- https://www.dsawsp.org/health/wood-smoke-is-pm

Hi Carole

I hope you enjoy the book when you read it. My big hope is that more and more people will do what you do and drive as little and considerately as possible.

I wonder if the traffic particulate emission stats included in the report you cite include non-exhaust emissions? Most of the particulate emissions from traffic now come from tyre, brake pad and road surface wear, not from the exhaust. Exhaust emissions have fallen massively but non-exhaust emissions have almost certain risen (although they are not monitored). One recent estimate suggests that non-exhaust emissions exceed those from combustion by a factor of hundreds, perhaps thousands, and that most of these fall in the PM2.5 category.

Best wishes

Paul Donald

Valid point. Thanks. Hadn’t considered that.

When I think that my mother used to go on holiday, riding on a donkey, following her parents in their pony & trap. Whoops – shows my age.

I will get your book asap. Paul.

Thanks Carole, I hope you like it!

Paul

And in a recent survey of people with wood stoves about 60% said they burn logs ‘because it looks nice’ – I’ve always suspected this, wood stoves were more about ornamental tree burning rather than legitimately heating homes. Given our terrible deficit of dead trees and wood then last thing we needed was driving a market for wood that’s seeing dead wood in nature reserves being pilfered to provide logs for stoves and many old trees that have stood in fields for years ending up as piles of logs.

The ‘conservation’ sector didn’t exactly help when it justified this by saying burning wood is carbon neutral, it certainly isn’t eco responsible – pretty bad when there’s more effort being put into saving coal than trees. Insulation, effectively plugging the hole in a leaky bucket, should have been by far the main thrust of the green sector, but wood stoves were supposedly ‘sexier’. I know that in London the canal boats which burn wood for heating are being targeted as a source of air pollution, they also result in a lot of messy dust which indicates that wood stoves are a source of in house particulate pollution too.

With the greatest respect, I imagine you have never lived where the electricity supply is erratic and in winter heating oil can often not be delivered. Our hill farm had three wood burners; one doubled as a water heater, the other two heated living rooms. All our wood was either naturally fallen timber or carefully coppiced; the latter providing habitat and good understory for wildlife. As for insulation, try achieving this in a seventeenth century house with no cavity walls, a roof full of long-eared bats. Swifts nested on the walls and house martins under the eaves. There would have been a conservation riot had we tried to change any of this. Believe me, these stove were not decorative!