Dr Emily Adams is a researcher, writer and manager who currently lives in Zurich, Switzerland, and works part-time for the British Association of Nature Conservationists (BANC). She has a PhD in Geography (studying beekeeping knowledge and engagement with science and policy), and a background in biology and conservation. She runs a small silk painting company, Wild Ties, specialising in nature and conservation designs, in her spare time.

Dr Emily Adams is a researcher, writer and manager who currently lives in Zurich, Switzerland, and works part-time for the British Association of Nature Conservationists (BANC). She has a PhD in Geography (studying beekeeping knowledge and engagement with science and policy), and a background in biology and conservation. She runs a small silk painting company, Wild Ties, specialising in nature and conservation designs, in her spare time.

Looking with skill: Nature, conservation and the need to engage

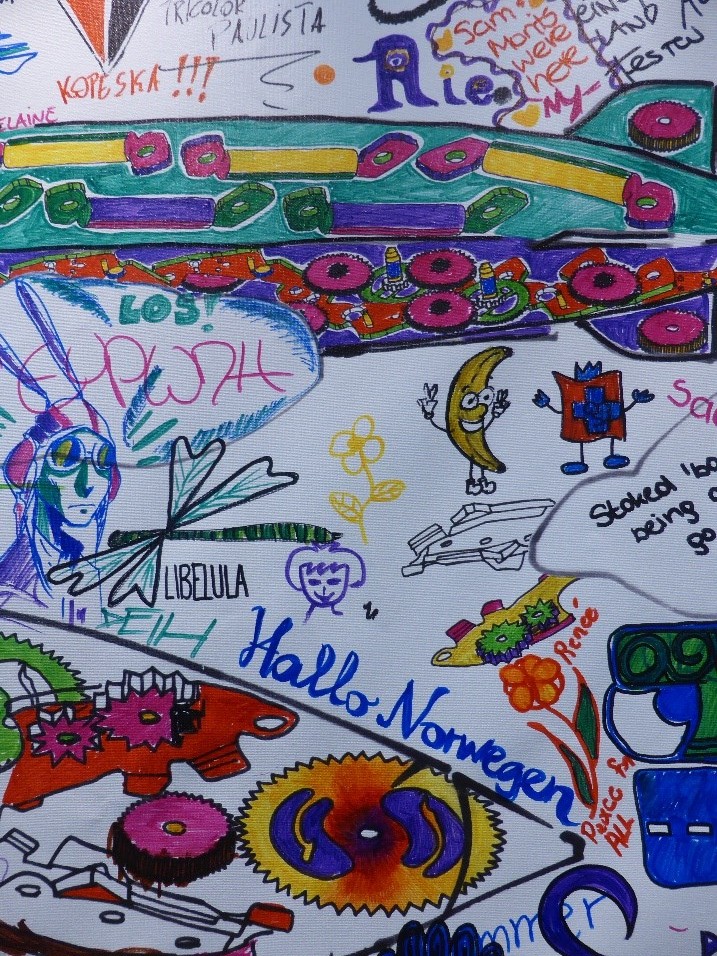

Why, when faced with an empty page and the invitation to draw something, do we so often default to nature as our inspiration? The trigger for this thought was an installation by Swatch, who had an art project in Zürich airport with giant canvases and lots of coloured pens to get people drawing as they waited for their flights. As an artist and biologist myself, I spent quite a bit of my waiting time drawing alpine flowers, but what interested me was how often nature featured in the drawings.

Most of the drawings I saw in the airport were simplistic, reflecting a limited perception or memory of nature. Yet, wildlife artists like Bruce Pearson manage to move beyond this simplistic memory of nature, to capture the ‘jizz’ of animals and landscapes, those characteristic features which allow us to instantly say ‘that is X species’ or ‘is this a painting of Y location?’ I am reminded again of Terry Pratchett, on the drawing of a tree: ‘Someone had drawn a tree… It was … as if someone had drawn trees, and started with the normal green cloud on a stick, and refined it, and refined it some more, and looked for those little twists in a line that said tree and refined those until there was just one line that said TREE.’ (Terry Pratchett, ‘The Last Continent’, p. 345).

How do artists capture nature so powerfully that their works speak of animals and landscapes? Pearson, on his website, highlights the importance of observation in his work: ‘The starting point has to be the field experience, as pure observation is the raw material’. Artists become skilled because they look, watch, practice and look again at their ‘raw material’ of nature, and learn to represent this in their chosen medium.

Observation is also central to the work of conservationists and ecologists: without the thousands of hours of painstaking observation of earlier natural historians and wildlife enthusiasts, we would know much less about the natural world around us. As technology has developed, we have been able to watch many more, smaller things like microbes and molecules, yet conservation still relies heavily on observing animals, plants and whole habitats.

I would argue that looking closely at something brings about love and care for it. Artists often love their subjects and conservationists often love the most unlovable of species and habitats. We, as conservationists, share the ‘looking’ practices of wildlife artists, for different ends but with the same result: a nurturing of something valuable to us. We love nature because we come to know it well through looking at it, engaging with it over time (often from childhood and throughout our training) and through our work.

Nature everywhere is under pressure: species and habitat loss are common, and despite the professionalisation of the conservation sector, we still struggle to make a positive impact on the environment. Can we harness ‘skilled looking’ to engage with those who are more disconnected from nature?

Returning to the airport doodles, the presence of nature in a place of sleek architecture and a distinct lack of natural habitat suggests that for many of us, there is something about nature that remains in our unconscious, released when faced with coloured pens and a blank canvas. Perhaps this indicates an instinctive human relationship with nature, as Wilson’s ‘Biophilia’ hypothesis implies. Maybe it just reflects the average childhood of picture books filled with royal elephants, peckish caterpillars and spotted canines, or adult TV watching habits of Spring Watch, BBC Planet and other nature productions? If the latter, it implies that children’s books (and adult equivalents) are important to passing a love for nature down the generations – without these cultural connections, the growing dissociation from nature, exemplified by the removal of ‘nature’ words from the Collins children’s dictionary in favour of ‘digital’ words and regarded as a key issue for environmental engagement (here and here), will be exacerbated.

The tendency to default to nature in doodles suggests that engaging people through art might be a valuable avenue for conservationists to explore further. Wildlife art in particular (whether photography, painting or other media) captures the ‘jizz’ of nature, invoking a sense of wonder in the observer. Wildlife art can encourage ‘embryonic’ lookers’ (who default to 4-petalled flowers in airports) to look again at nature, and engage more closely with it. There are some great examples of joint conservation-art projects already out there: Rory McCann paints wildlife murals, bringing vibrant, inspiring paintings of nature for children and adults into every-day environments like schools and nursing homes. Others, like sculptor Helen Denerley, reuse and recycle materials to produce animal sculptures that give new life to discarded materials. Perhaps of more relevance to practical conservation, creative collaborations between science and art can help inform people (e.g. the Ghosts of Gone Birds project), encourage constructive stakeholder engagement (e.g. the 2014 ACES project on human-wildlife conflict) or just help bring nature closer to home (e.g. Artists for Nature network).

Conservationists should be encouraged: despite living in an era where the environment appears at times further down the political agenda than ever and species and habitat loss continues, there is hope in the casual, every-day act of doodling. It can be a place to encourage an interest in and care for the environment. Next time you meet someone who doesn’t know much about the environment, or who expresses little interest in it, invite them to pick up a pencil and join you in some close observation of nature.

NOTE: A longer version of this appears on the Action for Conservation blog (or will do, when it is released).

[registration_form]

Thank you, Emily, for a thought-provoking article. I’m a writer, rather than a visual artist, and working with biophilia, ecotherapy and related concepts for part of my MA in Nature Writing, and as a psychological mentor.

I’m interested to read about the project in Zurich airport, though not surprised that many of the drawings are nature related. In a recent experiment (don’t have the reference right now) far more people told to draw a ‘thing’ on a blank sheet drew trees, flowers and animals than houses and cars.

Another interesting phenomenon, from both artistic and ecological points of view, is the recent flood of adult colouring books: the vast majority of which, again, are nature themed. And surely, that’s where ‘art’ began… with those ancient representations on cave walls…

I will be checking out some of your links. Thanks again.

Dear Daphne

Many thanks for your kind comments, it is my first blog post so I’m delighted that you enjoyed it, and even better, found it interesting.

I’d be really interested in the reference about the drawings, if you can find it. I’m in the throes of writing a paper about environmental stewardship and beekeeping, and it sounds like it could be useful. Also, it reassures me that it wasn’t just a Swiss tendency to love nature (what with the Alps being nearby and a plethora of clean and enticing lakes, many people here adore nature, going hiking and swimming regularly! And skiing too).

I have noticed the colouring book trend – it was quite striking when I was back home last time. Beguilingly therapeutic I’ll have to keep a look out for a cave-painting colouring book – surely just a matter of time, many of the images are very striking and intriguing.

I’ll have to keep a look out for a cave-painting colouring book – surely just a matter of time, many of the images are very striking and intriguing.

Best wishes with your MA – where are you doing it? It sounds like an amazing course!

Emily