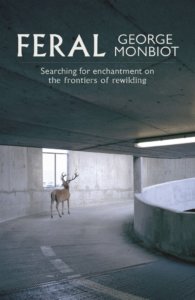

This blog’s recent writing competition was to write a review of George Monbiot’s book Feral.

The entries were judged by John Riutta, The Well-read Naturalist, Ian Carter and myself. Three entries were in the running for the winner (who receives a signed copy of my book Remarkable Birds) and I will publish the two highly-commended entries in future, but the deserved winner was Kerrie Gardner.

Kerrie writes: I work as an ecologist but behind the scenes I paint, sculpt, take photographs and write about the natural world. I find no greater pleasure than that which comes from immersing myself in nature, for there is joy to be found there which cannot be replaced. Diving into the dark sea, waiting silently for an otter or standing beneath a colossal thunderstorm; these are the moments I was made for.

Kerrie’s review of Feral:

Strangely, I didn’t buy Feral. My boyfriend did, in a small bookshop in Totnes. We had a long train journey ahead of us, so I reached into his bag and pulled out the book. And to my surprise, I couldn’t put it down.

It begins in the rainforests of Brazil. It is not an area I would normally choose to read about, being more interested in the boreal regions of the world. Yet as I sat there, eyes swooping from line to line, I felt deeply connected. There was something brewing in the words that called to me. It was then that Monbiot began to speak of Wales.

I have lived in Wales. I spent nearly four years of my life there, journeying deep into Snowdonia to walk up and down its many hills. Sometimes, on a rare day when I was feeling more sociable, I would walk with a Welsh friend. He was determined to climb every mountain in Wales. As such, he and I often travelled well off the beaten track. We even, on occasion, strayed into the Cambrian Mountains. I wrote once, after spending a day on their borders:

There was a smell

about that valley,

sheep,

streams,

waterfalls […]

Yet at the time I did not realise the significance of my words.

Monbiot refers to these mountains as a desert, 460 square miles of virtually uninhabited land. When he moved there from the city he felt he was fleeing a stagnated existence, but his initial joy soon gave way to despair. The area he had chosen to live, which sat between the Cambrians and Snowdonia, was almost completely devoid of wildlife. To his dismay, he found there had been more plant and animal life in London.

And it is true; it was this absence of wildlife that I had referred to in my poem. The only thing I could smell in that barren valley was water and sheep. There was nothing else, just the ‘tinkle of water and trudge of stone’.

As Monbiot points out, this is because the landscape has been ‘sheepwrecked’. All plant life, save a handful of species, is decimated by their grazing. A similar situation is also happening in Scotland, but there it is largely red deer that are to blame.

Highlighting how heavily subsidized hill farming is painfully unsustainable, both for the UK taxpayer’s pockets and the environment, Feral also shines a light back to a time before sheep existed in Britain. And it was a magical time indeed. For there were monsters; great beasts such as bison, moose, bears, lynx, lions, wolves, rhinoceroses’ and elephants, all roaming around in vast numbers. Huge forest grew where now there is only heather, and in the rivers and seas enormous creatures swam. The world before human interference was magnificent. It was beyond our wildest dreams.

Or not, and this is where Feral pulsed through my veins like electricity. I believe many people in the UK are suffering from what Monbiot calls ‘ecological boredom’. Our lives, for the most part, are not the adventures they once were. Too many of us go through the motions with a secreted unrest. Listen in to any conversation and you can hear it. People aren’t happy. I admit there may be any number of reasons for this, but the underlining reason, as stressed in Feral, is that we have become so removed from what we once were; hunter-gatherers who lived in a raw and ferocious world. But the memory of that existence still remains, locked up in our DNA. A fading dream of a time when our lives were full of gripping simplicity, not the busy tedium we find ourselves in now. And I understand this feeling. I understand it so well that I wanted to find Monbiot and shake his hand.

We no longer have any large predators in the UK. Consequently, our trophic cascade has failed. If there is nothing to eat the herbivores, trees cannot grow. Our landscape, once praised for its manicured emptiness, is in fact very sick. Increased flooding and an ever diminishing species list are just two of many warning signs that we are continually choosing to ignore. The necessity of predators, as shown by the reintroduction of wolves into the Yellowstone National Park, is paramount. Their behaviour, from bears to plankton eating whales, transforms the environment for the better. Critics argue that reintroducing predators, alongside other charismatic species such as beavers to the UK is idealistic, but with extensive research, Feral shows that the benefits outweigh the risks. In almost every other European country many of these creatures are returning, with their presence often facilitating an economic boost. Closer to home, the reintroduction of white-tailed eagles to the Isle of Mull brings in £5 million a year. In fact, wildlife tourism in Scotland is already worth £276 million a year. Deer stalking brings in less than half that amount.

But the key message in Feral, the one that resonated with my soul so intensely, is that while rewilding our land and seas is vital – so is rewilding ourselves. If we are to escape from our mediocre lives, we need to re-engage with the natural world. As Monbiot shows with refreshing zeal, his life feels infinitely more alive when he is surrounded by nature. His kayaking trips ignite him in ways that manmade amusements never could. When he is fully engaged with nature, the incredible creatures we shared this land with only a few thousand years ago become hauntingly close. Living among wolves and bison no longer seems implausible. Within Feral, we discover the very essence of wilderness. And it is not hiding in some remote place, but deep within us, buried beneath years of conditioning and bizarre agricultural policies. For we are feral creatures at heart; hemmed in only by our peculiar fear of ecological progression. But if we can just find the courage to let nature decide, our countryside and our society could pulse with life once more.

Feral: searching for enchantment on the frontiers of rewilding by George Monbiot is published by by Allen Lane, Penguin Press.

Feral: searching for enchantment on the frontiers of rewilding by George Monbiot is published by by Allen Lane, Penguin Press.

My own review of the book is here.

Buy your copy of Feral from Blackwell’s and I will earn a little bit of money too!

[registration_form]

Mr Monbiot’s solution to biodiversity is hunting

‘Monbiot is clearly a hunter at heart…..’

‘…it’s clear from his prose that he loves the thrill of the hunt and the kill….’

https://anewnatureblog.wordpress.com/2013/09/03/feral-by-george-monbiot-a-review/

But he will expect the long suffering taxpayer to fund his hunting; nice work if you can get it.

‘The number of lambs lost to white-tailed eagles on Mull which was estimated to be around 35 lambs per year over the period 1999-2002.’

‘The number of lambs lost to foxes in mid-Wales which was reported to be 3,134 from 1995 to 1997, or around 1,567 each year.’

‘…..the case of Norway, where an estimated population of 600 lynx killed 18,924 sheep over a 3 year period…..’

https://www.aecom.com/uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Cost-benefit-analysis-for-the-reintroduction-of-lynx-to-the-UK-Main-report.pdf

How would elephant numbers be controlled?

‘…..it is unlikely that Zimbabwe held more about 4,000 elephants in 1900….in 2014, this number had increased twenty-fold to nearly 83,000 elephants….despite attempts to limit elephant population growth between 1960 and 1989 by culling 45,000 elephants…..Elephant impacts on woodlands and associated and biodiversity is still a concern today’

https://conservationaction.co.za/resources/reports/zimbabwe-national-elephant-management-plan-2015-2020/

Has this been thought through….really?

Tim Bidie – that will come as a surprise to George I reckon.

Maybe….or maybe not:

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2009/aug/22/george-monbiot-fishing

Tom Bidie – maybe Mark would consider awarding another prize – for best pile of cherry-picking and distortion. This is a masterpiece!

Just to take one example. You choose to mention the rates of sheep predation by lynx in Norway. The article you link to does indeed report relatively high losses, but it goes on to say, “As shown in Table 2, the recorded number of sheep killed by lynx is zero in most countries in Europe… Livestock damage is almost unknown in natural lynx populations in central and eastern Europe… The one outlier is the case of Norway…due to the particular sheep farming practices adopted in this area. Unlike in most European countries, sheep in Norway are grazed free range and un-shepherded in forest areas which leads to higher predation rates by lynx. In the rest of Europe (and in the UK), sheep are typically grazed in open pasture and predation is either non-existent or small-scale and localised.”

Well done for choosing to mention ‘the one outlier’, rather than the 17 other European countries that have lynx populations. But I’d have been disappointed if you hadn’t.

Tim – apologies for mis-typing your name.

Alan Two – it is a very good example, but this is a master of the technique as regular readers of this blog will know well.

Re the lynx killing sheep in Norway that’s the exception that proves the rule – in Norway sheep are, very unusually, often grazed right into woodland in the sort of areas you would usually get the lynx’s preferred prey the roe deer. I would also say that some farmers have been known to make exaggerated claims about supposed losses especially when there’s compensation available (I recall that years ago a scandal blew up in Norway re farmers making fraudulent claims for livestock losses to wolves, bears, lynx and wolverines) – or am I just being a naïve townie who believes that farmers aren’t gods, but people with potentially the same failings as the rest of us mere mortals?

Not sure the figure for deer stalking is a +plus. Take in all the fences that have to be put up to protect forests and private gardens which the estates don’t pay for and you end up with a -minus. One example on Mull only 3 estates use deer stalking but the island is covered in deer fencing! Add on all the wildlife that are killed by these fences like Capercaillie and other game birds!

Great review though. Can’t wait for his new book out soon.

I guess Mull has few hedges? or what about the car crashes? My wife stopped sharply as three red deer bolted through a gap in the hedge; the fourth left a snotty nose mark on the drivers window and bent the door in. Seemed to run off OK and the neighboring farmer found no body.

Well taken and composed portrait.

Thanks Kerrie and congratulations.

As for ‘rewilding ourselves’, are we any less ‘connected’ compared to people in the deep past? What about the many mass megafauna extinctions across the world courtesy our Palaeolithic forebears? They were no different from us: deadly efficient hunters; ingenious technologists and fabulous artists. Undoubtedly too, they waxed lyrical about their natural world in the same way as we do.

No, the problem is right there in our DNA.

But there’s hope. It resides in the biggest animal that has ever evolved on this planet. Twentieth Century man tried very hard to exterminate it but, thanks to a minority of moral and intelligent people, the Blue Whale is still with us.

I liked the review. Maybe the desire to rewild our land is linked with the desire to re wild ourselves. It is hard to argue that this society/culture is not profoundly sick in many ways. That something is missing.

Tourism: I cannot see how a secretive, camouflaged feline that likes dense woodland to hunt in (the Lynx) is compared as an attraction to the tourist to the results of introducing a great big bird that flies high in the sky and sits on top of things. One has to wonder about the proposers judgement about other things.

The review is a good description of the thrill to some of nature. Maybe just more woodlands to escape into without the need for a major predator (?) but then again signs saying “keep you dog on a lead” with a picture of a Lynx beside it may be induce people to do just that!

“reintroducing predators, alongside other charismatic species such as beavers to the UK is idealistic, but with extensive research, Feral shows that the benefits outweigh the risks.” very omnipotent but what about the devil of unintended ( unforeseen consequences). Which makes me wonder with badgers now the top predator (man) has been (mostly) removed from the action and they are proliferating and hedgehogs declining what controls badgers in the future? Disease? TB? so we are now to immunise them against TB ??? What does research show as the next step in the game is going to be??

Alan, I don’t think Kerrie is directly comparing White-tailed Eagle with Lynx. I would add though that Lynx tourism is now a significant business in Spain following the re-introduction/reinforcement programmes there, albeit not on the same scale (yet?) as Mull.

Sorry Andrew, I meant “Andrew” not “Alan”.

The review is a very good summary of the book. It is interesting that it is from a woman, as some critics of the book said that Monbiot had a male perspective on nature. The comments above about Monbiot as a hunter may be related to this view, although they don’t seem to be well argued to me.

I bought and read “Feral” when it came out in 2014 and personally the best bit in it is where George advocates just leaving large areas alone to regenerate themselves. Admittedly this will possibly take a long time, but in the end letting nature work at its own pace to me seems the best way forward. I am a member of the Borders Forest Trust and it purchased the Carrifran Valley (Southern Scotland) about 20yrs. ago. Although many native trees were planted, it is amazing how other plant life, insects, etc. have come back.