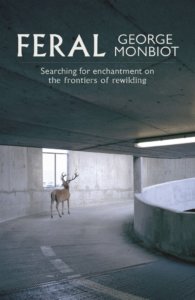

This blog’s recent writing competition was to write a review of George Monbiot’s book Feral.

The entries were judged by John Riutta, The Well-read Naturalist, Ian Carter and myself.

The winning entry by Kerrie Gardner was posted on Sunday. Two more entries were highly commended and this is the second of them, by Peter Anderton.

Peter Anderton @PeterAnderton7 is a walker, cyclist, runner and general outdoors enthusiast. Keen advocate for green spaces and walking/cycling as normal and key to health. Mancunian on the wrong side of the Pennines.

Peter Anderton @PeterAnderton7 is a walker, cyclist, runner and general outdoors enthusiast. Keen advocate for green spaces and walking/cycling as normal and key to health. Mancunian on the wrong side of the Pennines.Feral is a book full of challenge: to our safe, settled lives; to accepted notions of farming and rural land use; to orthodox conservationism.

Although meticulously argued, his suggestions are at times so provocative that doubtless some conservationists (as well as all sheep farmers) think that Mobiot himself has gone feral. I suspect he would not object, as in a sense, this is his aim.

Feral narrates Mobiot’s journey (one might even call it a pilgrimage) toward a closer relationship with the natural world; his twin themes, of rewilding of the heart, and rewilding of nature, woven through the text. Monbiot’s via cordis takes us from his experiences with Maasai warriors in Kenya, through the violent chaos of Amazonian gold mines, to what he terms the ‘Cambrian desert’ of mid Wales, (desecrated by the pervasive monoculture of sheep and grass), and, cresting the breakers of Cardigan bay, to a destination of the spirit, marked on no maps.

Feral sets out a depressing backdrop of environmental degradation, with collapsing fish stocks and dwindling biodiversity on sea and land alike, perpetuated by the perverse incentives of publically-funded farming subsidies, and fishing quotas. The comparison of current puny catches with fish shoals that would formerly stretch for miles is quite shocking.

Attempts at rewilding, or the creation of fishing-free marine reserves, are often met with intransigence and suspicion from the inherent conservatism (and understandable economic anxieties) of farmers, fishermen, landowners, and the politicians in their sway. It is particularly disheartening that this opposition is in the face of scientific evidence suggesting that such moves would be positive, not only for biodiversity, but also in terms of economic productivity. For instance, creation of meaningful marine reserves would quickly allow more fish to be caught in other areas. Rational science is clearly no match for strongly held opinions in 21st century Britain, however (which has famously, according to one recent politician, ‘had enough of experts’).

Feral takes issue with the curationist approach of many conservationists (backed up by EU subsidy rules) to preserving habitats, such as the deforested, extensively grazed uplands present across much of mainland UK. This habitat is man-made (by clearing and grazing) and the maintenance of the current status quo, at enormous public expense, is a choice. Whether the productivity in terms of food, employment and aesthetics is something that should be maintained, or whether a more diverse forested upland would be preferable, is controversial. The current state of affairs is so extreme, however, that some form of enrichment can only be a boon.

Monbiot is at pains to insist that changes to rural land use, such as he proposes, should be implemented with the consent and involvement of those living and working in rural communities, even as he despises the existing bleak, featureless, landscapes. Equally importantly, Feral does not propose changes to use of productive lowland agricultural acreage, lest we all starve.

So far, so gloomy. Rightly observing that environmentalists are more noted for what they oppose than for any positive vision of the future, Feral enthusiastically advocates a rewilding of the natural world. It persuasively argues for a careful reintroduction of lost species to (largely upland and remote) habitats, and for creating space for ecological complexity and interest to emerge. Rather than decide precisely how natural landscapes should look, and trying to freeze naturally fluid ecological relationships, rewilding in this sense advocates a degree of freedom to the land to develop rich and sustainable ecosystems. These would enhance not only the robustness of the environment, but also its beauty and corresponding wonder.

Monbiot’s suggestions include such headline-grabbing ideas as the reintroduction of wolves to rural Britain. Written with characteristic scientific rigour and careful explanation, there is actually nothing cranky or romantic about the proposal. The reintroduction of small numbers of predators, as well as other key missing species (especially beavers), has remarkable potential to improve the whole ecosystem, via trophic cascades, and should be considered with an open mind.

Purely in terms of the applied science, Feral is an important book, worthy of widespread consideration, and I urge you to read it. Yet it is the interior narrative, Monbiot’s deeply personal engagement with the natural world in a quest to escape the ennui of modern living, that makes Feral such a lucid and engaging read: a text of heart as well as head.

Acknowledging the many material benefits of modern society, Monbiot nevertheless feels that something vital has been lost. He seeks a more direct and engaged life, ‘richer in adventure and surprise’ than one in which ‘loading the dishwasher presented an interesting challenge’. Monbiot’s approach is to find this within wilder, more diverse landscapes than the often tamed and etiolated ‘managed’ landscapes of much of rural Britain. In its own words, Feral proposes an environmentalism that ‘offers to expand rather than constrain the scope of people’s lives’.

Feral is a search for lost wonder, and for wild places that may induce wonder and peace; what Robert McFarlane in The Old Ways terms xenotopias, places where ‘we feel and think significantly differently’. Crossing uncharted borders, writes McFarlane, ‘such moments are rites of passage that reconfigure local geographies, leaving known places outlandish or quickened…’ For Monbiot, this calm is always found at sea, alone in his kayak: ‘The wind ravelled through my mind, the water rocked me. Nothing existed except the sea, the birds, the breeze. My mind blew empty.’

Feral offers encouraging examples of the resilience of the natural world, tales of renewal and reversal. Ecosystems are no more static than landscapes, changing and adapting over time, for good as well as ill. Whilst Feral brings the bleached, monochrome state of many British landscapes into sharper focus, it offers hope that, if only we have the will, a richer, more complex nature, brimming with wonder, is waiting to germinate.

Feral: searching for enchantment on the frontiers of rewilding by George Monbiot is published by by Allen Lane, Penguin Press.

Feral: searching for enchantment on the frontiers of rewilding by George Monbiot is published by by Allen Lane, Penguin Press.

My own review of the book is here.

Buy your copy of Feral from Blackwell’s and I will earn a little bit of money too!

Well done, Peter, a very thoughtful review.

Its interesting that many of the ideas that are seen as too ‘wild’ (!) are moving centre stage much faster than most people might realise – Unlike most of the conservation sector who remain stuck in the sectoral 20th century, Defra appear to be taking the work of t6he natural capital Committee seriously, and Brexit creates exactly the cracks in the monoliths we’ve all come to expect needed to do something different – for example, they’ve spelt out that we could have higher fish yields forever.

I suspect most ecological professionals who know the uplands would actually see Monbiot’s comments about the Welsh uplands as if anything understated – I was profoundly shocked by my last visit to the Cambrian mountains. And we shouldn’t translate ‘more trees’ into blanket Sitka – OK, there might be a place for more timber-oriented conifers, but at least we’re talking about trees up streamsides which would have been there till the sheep blight, further, the large scale native woodland development in the Trossachs.

Where Monbiot doesn’t go far enough – but the NCC does – is bringing nature to our doorsteps – NCC recommend 250,000 hectares of community forests around our towns and cities, just 2% of the land area which is hardly going to bring on instant starvation. The impact on lives, the environment and our ability to build more houses whilst enhancing rather than destroying the environment is massive – and so far largely overlooked.

Roderick, it’s great to read this, especially your last para. Yes, there’s loads of space everywhere — for houses, agriculture and nature. We are all blind to the fact.

In the land of the blind, the two housed man rules supreme. But not for much longer.

Before the vote for Brexit, the ‘Establishment’ – according to a claim by the Deputy Editor of the Financial Times – wanted a UK population of 80 – 85 millions (to rival Germany – whose population was falling at the time – within the EU). Some people may ‘think’ that there’s plenty of space, and that ‘instant starvation’ is unlikely, but… the UK provides just less than 50% of the food that it requires to survive. Then there are the mineral resources and fresh water required to support a rapidly increasing population. The reality, today, is that Green Belts are being eroded at a quickening pace in order to house our accelerating population growth. Trees, ancient woodlands, and established forests are being destroyed for this ‘economic growth’. The coup-de-grace from this uncontrolled population growth will come from nature herself: climate change will render food production incapable of supporting all of us. I am 100% in favour of re-wilding, but ANY idea that we have “plenty of space” – without regard to population growth – does not understand what we need to survive as a modern civilisation.

Peter, that’s another good review. It’s fair, comprehensive and well written. It more than fully deserves the ‘highly commended’ tag in this writing competition.

My only criticism is your lack of explanation of the ‘trophic cascade’ – a relatively recent term for an ecological process that is essential for healthy ecosystems. Monbiot’s thesis relies heavily on this concept. To be honest, it’s new and exciting to me. So I bet lots more people could be made to feel the same way, if only they could be made aware of the idea. Nevertheless, your review will undoubtedly get others to read Feral. And that’s good.

Thanks for the nice panorama with that threesome wolf pack by proxy – it just needs a tree or three for real.

Thanks for the comments. I would love to see community forests, preferably capillaried with tracks to walk and cycle. Fantastic idea.

The point about trophic cascades is well taken. I was constrained by the word limit, but I agree the concept deserves some more unpacking and perhaps should have been more central.