Nick MacKinnon is a freelance teacher of Maths, English and Medieval History, and lives above Haworth, in the last inhabited house before Top Withens = Wuthering Heights. In 1992 he founded the successful Campaign to Save Radio 4 Long Wave while in plaster following a rock-climbing accident on Skye. His poem ‘The metric system’ won the 2013 Forward Prize. His topical verse and satire appears in the Spectator, and his puzzles and problems in the Sunday Times and American Mathematical Monthly. Email: [email protected]

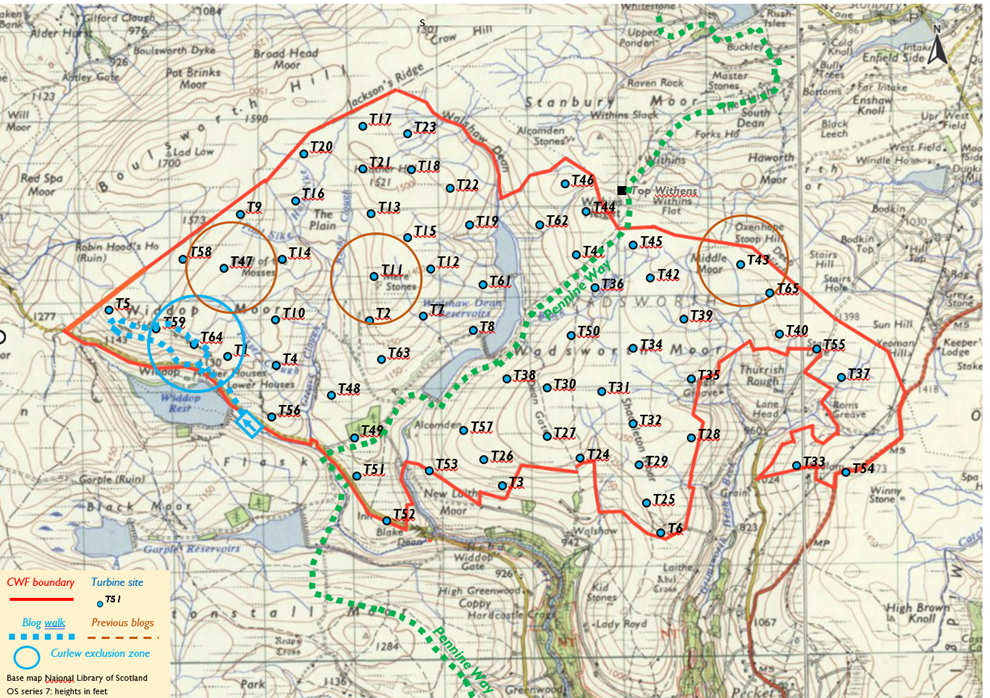

Turbine 64: The Lumps SD 933 336, what3words ///bribing.signature.paid

22 January 2024 Storm Isha has gone over, leaving behind sharp showers and a gale in a ravelled sky. The wind farm at Ovenden Moor is stationary; the turbines were upgraded in 2016, and can withstand 150 mph, so the shut-down will be because too much wind generation is being dumped onto the grid by the storm’s tail. Octopus Fan Club members in BD22 and HX7 get no tariff reduction today; had the fans been spinning, it would have been 50%. The owners still get their subsidy, a reward for not adding to grid overload. As the Ouija board of what3words puts it: ///bribing.signature.paid.

The other Calderdale farms are spinning fast: there is a curse on Ovenden Moor: on my walk to T43 last week when the snow was squeaking in space-blue air, Ovenden was again stationary while the others spun. In Dance to the Music of Time, Anthony Powell recorded what debs said to frustrated young men at coming-out balls in the 1920s.

“Don’t do that, darling: I don’t love you enough!”

“Don’t do that darling: I love you too much!”

On my last field trip to Ovenden, doom lay heavy. Fly tipping was endemic, the heather was crispy, and the squat substation was surrounded by Siemens Electric vans like the siege of Antioch.

The laminated OL21, regional finalist in Britain’s Most Useless Map, shows no paths up to the Scout, the rocky edge above Widdop Reservoir, but Christopher Goddard’s West Yorkshire Moors gives a steep path right of the Raven from a passing place 400m beyond the car park. The rocks here form hundreds of short puzzles for boulderers, who climb with chalky fingers and stealth technology plimsolls, protecting themselves with a crash mat. Across the reservoir, Widdop Wall (ED 7a***) is the 20th hardest you-may-die rock climb in Britain, and waited for over a decade between its first and second ascents by John Dunne and Jordan Buys. The UKC rock-climbing guide shows more love of this place than its owner, Mr Bannister.

The Scout is the sprawling jumble of boulders and craglets lining the edge of the vast moorland opposite the popular venue of Widdop basks in relative obscurity. This is partly down to the history of restricted access. Scout has a sunny aspect, a quick-drying nature, very rough grit, and steep climbing above generally good landings. The superb moorland setting and far-ranging vistas across Widdop and the moors beyond seal the deal on a fantastic and grossly underrated grit venue.

The boulderers have indeed made a faint desire path straight up from a passing place. The gale is hard from my left, and by resisting it sideways, I get what sailors call a broad reach, and in twenty minutes am on top of the Raven.

Now I must turn straight into the wind and beat along the Scout. It’s a manageable Force 8 (foam blown in well-marked streaks; twigs break off; generally impedes progress) but the sharp edge creates turbulence which repeatedly whips my beanie hat off. Without the hat, the wind syringes my ear. I am a curlew in the vortices thrown off by a turbine blade. Between retrieving the hat from some overhanging version of Twister, and taking photographs while the i-pad throbs in clenched fists like a defibrillator, the 500m from the Raven to the Lumps, and the site of Turbine 64 takes thirty minutes.

Storm Isha becomes more solid as I tack up the hill from T64, but as the edge recedes there is less turbulence. Grey Stone Hill is the high end of the gently sloping Scout ridge. The photo is from T5, with Lad Law visible as the summit of Boulsworth Hill, and the Dove Stones scattered on the watershed of Britain, which you can easily follow to Watersheddles Reservoir, where the line dives underwater and swimming is not permitted. If you decide to carry on to Cape Wrath, then study the Scottish section before you buy your Kendal Mint Cake, for over knottier ground the watershed becomes a wild fractal of indefinite length.

The Dove Stones have the strongest charisma of any of the landscape features in CWF, so Mr Bannister, whose family motto must be BRING ME THE HORIZON (Latin is classier: AFFERTE MIHI ASPECTUS) has either told his consultant Muttley to stick T58 right next to them in a giant raised finger to his tormentors, or Muttley decided to do this all on his own, boss-sabotage being an aspect of his character (wheezy snicker). Crown Point Flat spread below will be a main entrance to CWF and will host a borrow pit, stone crusher, concrete batching plant, caravan site, offices and eventually the substation and battery.

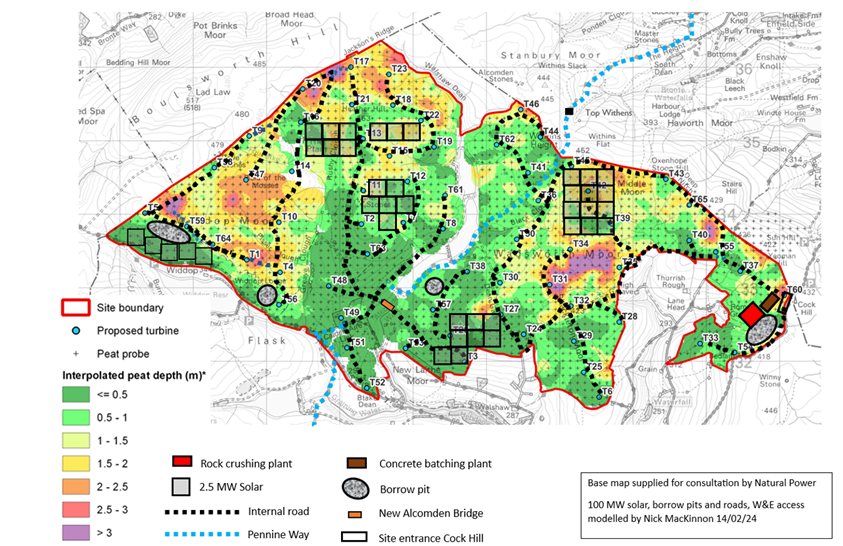

In what the CPRE thought was otherwise much too complex a scoping document, Muttley has been totally silent about the access, internal roads system, borrow pits for aggregate and the solar array. Partly this may be discretion. Imagine him trudging across the moor with his three-metre peat probe and coming across a well-engineered track that the Gold Standard digital OS 1:35000 doesn’t seem to know about. I wrote to Muttley, asking him if he was surprised to find an excellent track along the backwards question mark from west of High Greave to the Top of Stairs in the SE of CWF: no reply yet …

I have constructed what I call a model of CWF infrastructure. I find this useful when trying to imagine the full package. The map base for the model is the public domain peat depth survey in Muttley’s Scoping Report. I don’t trust it, and Ban-the-Burn are going to check his homework. The most obvious fault is that what is shown as dark green is nearly all at least 40 cm deep, but a casual user might think it meant “no peat”. Except on the actual outcrops, Walshaw Moor is covered in peat. I shall discuss the access and internal road system in a later blog (T35 Flaight Hill). Let’s start with the solar, which the scoping report is silent on, except to say that there will be some.

With the wacky logic that pertains here, the solar array in cloudy CWF is bound to be very large. It is absurd to deploy solar panels in the Pennines because it isn’t particularly sunny. The same resources deployed in Spain’s vast emptiness would produce twice as much electricity. But if you have already paid for the land, planning, cabling, service roads, substation, battery and grid connection to Rochdale by building a wind farm, a solar array is “Buy-One-Get-One-Half-Price”. The investor compensation for weak sunshine is free infrastructure, so it is Muttley’s duty to make maximum use of it. I assume 100MW of solar, achieving some proportion with 300MW wind. The rule of thumb in large arrays in the sunny south of England is about 1.5 ha per MW. There are 1200 hours of sunshine per year at Malham Cove but 1500 in the south of England, so I have reckoned on 1.9 ha per MW at CWF. The north-south grain of the site imposed by Greave Clough, Walshaw Dean and Mare Greave leaves little south-facing land and I have covered it. The strip along the Widdop road looks most vulnerable to causing outrage. I don’t know what the solar will do to the peat and hydrology but sealing 230 ha of the steeper water catchment with impermeable panels isn’t going to slow the flow, is it?

In the lee of a boulder I reef the map down to a half fold and plot a descent. The sun had gone into Lancashire as I turn and run before the gale. A sheep path takes me gently across the incipient clough between Fold Hole Top and Great Edge Flat, where Muttley will be digging a huge borrow pit, then I crash down dead bracken through 12.5 MW of solar array, to the calculable texture of the Widdop Road. It had been a jolting two hours, but the next ninety minutes getting home to Stanbury in the car will be harder on the nerves.

In our walks to the turbine sites, we mustn’t forget the outlook of less physically able people, and the busy. Many people’s experiences of the wind farm will be from the Widdop road, which may be a desperate Lancs-Yorks commute, but is also an awe-inspiring drive, more so even than Oxenhope-Hebden, or Stanbury-Colne. It is tough living in the South Pennines under everybody else’s rain, in a Piranesi etching of a ruined industrial revolution, but one compensation is this constant exposure to the gothic sublime. The turbines along the rocky edge will disenchant somewhere eerie and wonderful for everyone who passes in a car. The sat-nav now proves the point about gothic sublime by taking me into The Twilight Zone.

The screen shows the route as a fluorescent green Möbius strip. After a wooded corniche and hairpin, I am on some cobbles going past a White Lion pub. Twenty minutes later, after another wooded corniche and hairpin I go past the White Lion again. Then … but local readers know what it wanted next… a turn down a very steep car-width lane. At the bottom is a footpath and laminated sign saying TURN ROUND. Instead, I follow the sat-nav’s last wish into Lumb Bank and stop outside Ted Hughes’s back door. An aproned Ariadne comes out of the kitchen to say, “Either reverse very carefully to the turning place, or have a go turning round, but good luck with that!” With all sensors in ceaseless turmoil, I begin a 30-point turn, in the middle of which I think I am wedged forever between Ted’s railings and Ted’s retaining wall, a pike “jammed past its gills down another’s gullet”. At manoeuvre 25 the sat-nav considers I am going to escape the labyrinth after all, and insouciantly lights up a route via Blackshaw Head and the switchbacks. The explanation is either electronic terror of the Fox and Goose junction, with its fabulous co-operative pub where the beer glasses have a liquid line, or the long half-life of the Mytholmroyd minotaur’s animal magnetism.

We encourage artists to make their responses to CWF. This meme on theme of “Gothic Sublime” is by “Wuthering Hikes” a local artist who makes left-field Brontë-inspired work. The original wood engraving is by Fritz Eichenberg

This is the 4th in a series of 65 guest blogs on each of the wind turbines which Richard Bannister plans to have erected on Walshaw Moor. Turbines 11, 43 and 47 have already been described. To see all the blogs – click here.

[registration_form]

If someone had told me last year that anything good could have come out of a proposal for a wind farm on Walshaw moor, I would certainly have called them bonkers. I have been proved wrong.

Just as that famous wordster, Filbert Cobb recedes into the distance, presumably with the good woman Hazel in tow, up pops Nick MacKinnon to provide the light relief.

I will write to Mr Bannister and thank him, maybe asking for a few more turbines at the same time.

Keep up the good walk sir.

Excellent blog Nick, it’s been nearly 40 years since I was last up there, dodging Saville’s gamekeepers. You’ve inspired me, I must get back up there again!