Dr Ruth Tingay is a raptor conservationist with field experience from North & Central America, Europe, Africa, Central and SE Asia. She studied the critically endangered Madagascar Fish Eagle for a PhD at Nottingham University and is a past president of the Raptor Research Foundation. She’s currently researching the illegal persecution of raptors & its link with driven grouse shooting in the UK uplands. Here’s her fourth report from the GWCT 10th North of England Grouse Seminar, 17th Nov 2015, Ripley Castle, Yorkshire (episode one here, episode two here, and episode three here).

This blog is about a presentation given by Dr Sonja Ludwig (GWCT Senior Scientist) entitled, ‘Raptors and grouse – what have we learned from Langholm?’ The blog has been split in to two parts: this one will cover Sonja’s talk and the next one (later in the week) will cover the question and answer session that followed, during which a bombshell was dropped.

Sonja’s talk began with a lengthy description of the Langholm Moor Demonstration Project, known to many of us as simply ‘Langholm 2’. To save space, I won’t repeat it all here as this information can be read on the project website. The relevant bit was that Langholm 2 has been running for eight of its ten year duration and two of the three main targets had been achieved: 1) Extend and improve the heather moorland habitat; 2) Meet the SPA target of hosting seven breeding female hen harriers. The third main target, to support a financially viable driven grouse moor by killing 1,000 brace of red grouse per annum, has not yet been achieved.

Sonja described the various techniques that had been employed to achieve the first two targets, including the removal of sheep to reduce grazing pressure, a re-established regime of heather burning and cutting, a programme of heather restoration including the re-seeding of areas that had been affected by an infestation of the heather beetle, and the diversionary feeding of hen harriers. She told us that the spring density of red grouse had tripled and there had been an increase in red grouse breeding success, and “limited recovery” of waders such as curlew and golden plover. However, despite all this work, not a single red grouse had been shot. According to Sonja, this was because the post-breeding density of red grouse (as measured in annual July counts) was “only 80 birds per km²” which was low in comparison to post-breeding densities recorded on other English and Scottish moors and “shows that we still have a long way to go before sustainable driven grouse shooting can happen at Langholm”.

I was surprised to hear Sonja comparing this post-breeding density with that of other moors in Scotland and England as justification for not yet shooting at Langholm. Earlier in the day we had listened to two presentations (see here and here) that had shown a strong relationship between excessively high densities of red grouse and disease transmission and we’d heard clear warning that these artificially high breeding densities should probably be reduced. For example, Dave Newborn had told us that in July 2014, the mean post-breeding density of red grouse on 46 moors that GWCT had monitored across the north of England was an incredible 382 birds/km². That’s a hell of a lot of birds in a small area and surely isn’t a benchmark for good practice!

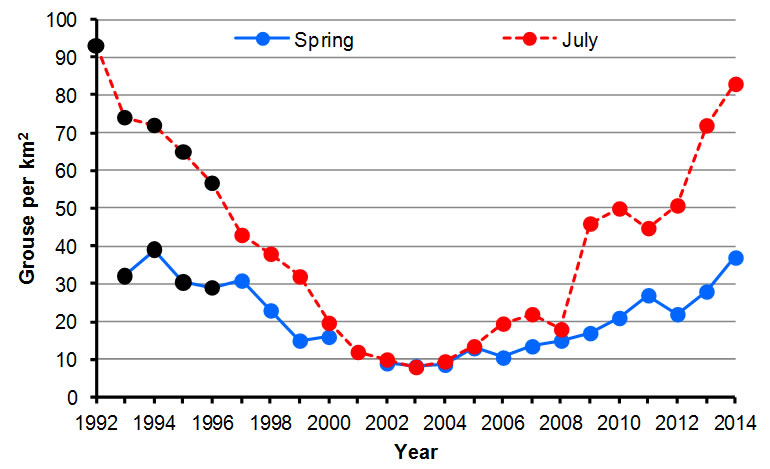

According to the Langholm 2 project specifications, the target mean post-breeding density for red grouse at Langholm has been set at 200 birds/km². In other words, the project board has decided that driven grouse shooting won’t take place until this figure has been reached. 200 birds/km² is an interesting figure. According to a 1992 GWCT publication, driven grouse shooting is recommended only when a July count is above 60 birds/km². If that recommendation was being followed, the current density of 80 birds/km² at Langholm would be high enough for driven grouse shooting to commence. Indeed, if you look back at what was happening at Langholm in the early 1990s, driven grouse shooting was taking place when post-breeding densities were only at approx. 75 birds/km² (see graph below), which is less than the current density.

Legend: The mean densities of red grouse at Langholm Moor in spring and July derived from block counts. Black symbols show years in which grouse were shot. Reproduced from Stuart Housden’s blog (23 December 2014)

Legend: The mean densities of red grouse at Langholm Moor in spring and July derived from block counts. Black symbols show years in which grouse were shot. Reproduced from Stuart Housden’s blog (23 December 2014)

So why has the target been set at 200 birds/km² at Langholm? It’s almost as if it’s been set ridiculously high to reduce the chance of the project being seen as a success. I’m not the first to point this out – see Stuart Housden’s blog here and Mark’s blog here but it’s worth reiterating again because it’s such an anomaly. The most important thing, though, is that the graph from Stuart Housden’s blog (which is simply a figure from the Langholm 7 Year Review report, redrawn to be clearer) shows that red grouse numbers are recovering at Langholm. They had recovered, in 2014, to densities that had allowed driven grouse shooting in the early 1990s when grouse densities were measured at this site using the same methods. Around 1,500 grouse were shot at Langholm in 1992 – that’s a respectable number worth thousands or tens of thousands of pounds – yet during the current project they decided not to shoot any. How strange.

The next part of Sonja’s presentation focused on what she described as “factors affecting the recovery of waders and red grouse” at Langholm. She said two problems had been identified (for the perceived lack of recovery – although as we have seen, red grouse were recovering and had recovered to shootable levels) and these were (a) low productivity of red grouse and (b) a low annual survival rate of red grouse. She suggested that heather coverage/habitat wasn’t limiting grouse recovery because results had shown that red grouse breed just as well in areas of 20% heather coverage as they do in areas with 80% heather coverage. Then she got to the inevitable issue of predation.

She told us that 90% of the birds that had been found dead (discovered either via radio-tracking efforts or just found randomly) “show clear signs of being predated”. She said that 80% of red grouse found dead in the summer and 65% of those found dead in the winter “show signs of being predated by raptors”. Evidence of fox predation was much lower in both seasons and there was also “the odd road-kill”. Of course, had there been shooting, the winter losses to predators would have been lower in absolute terms, because the losses to men and women in tweed would not have been zero.

She went on, “So basically we can say that the majority of birds seem to be killed by raptors on Langholm, and the problem with this is although we can tell basic field signs that a bird has been killed by a raptor, we can’t tell for sure by which raptor species”.

That’s quite a statement to make. I’d like to know how they determined whether a grouse had been killed by a raptor or whether it had simply been scavenged after the grouse had already died. But I’ll come back to that.

Sonja said that they were currently trying to look at the effect of different raptor species on red grouse at Langholm, to estimate their “relative contribution to predation” and this had been done indirectly by looking at the proportion of red grouse in the diet of three different raptor species and then population modelling software was being used to estimate the relative impact of the different raptor species.

A variety of different methods had been used to estimate the proportion of red grouse in the diet, including observations, cameras, and analyses of pellets and prey remains. I was quite impressed with the range of methods employed; many studies come unstuck because they only use one, or at best, two methods, which can produce notoriously biased results. By using four separate methods, there can be some confidence in the results, which were as follows:

Proportion of red grouse in the diet of hen harriers = 0-4%.

Proportion of red grouse in the diet of buzzards = 1-6%.

Proportion of red grouse in the diet of peregrines = 5-14%.

Sonja explained that the variation in the figures related to the method of analysis employed and the number of breeding pairs of each raptor species at the time of the analyses (an increasing number of breeding hen harriers; 9-15 breeding pairs of buzzards; 2 breeding pairs of peregrines).

To me, these robust results do not support the claim that raptors are killing lots of red grouse, or even eating lots of already-dead red grouse at Langholm, although they are eating some, of course. The results do show that diversionary feeding of hen harriers is working well; in the Langholm 1 project it was found that the proportion of red grouse in the diet of (non-diversionary fed) hen harriers was 12%.

Explaining the buzzard results, Sonja told us that Richard Francksen’s recent PhD study had found that red grouse are only ‘an incidental’ part of the Langholm buzzards’ diet, and that red grouse predation was linked to vole abundance on the moor. In years when vole abundance was high, more buzzards were seen hunting on the moor and there was a higher proportion of red grouse in the buzzards’ diet during those years. [Richard was at this seminar but unfortunately he wasn’t giving a presentation on his work].

It was at this stage of Sonja’s presentation that I found things hard to follow. She said that Richard had tried to estimate the impact the buzzards can have on the red grouse population and had found that spring predation varied from 5-26% and winter predation was 10%. Unfortunately she didn’t explain how these figures had been produced, nor what they were supposed to represent, nor the wide variation in the results. I’m guessing that she was talking about the percentage of so-called ‘known raptor kills’ found during the spring and winter seasons that could (apparently) be attributed to buzzards but don’t quote me on that because I’m really not sure. I guess we’ll have to wait for Richard to publish his results. Sonja told us that “similar calculations” were being done for hen harrier and peregrine but no results as yet.

Sonja ended her talk with a quick review of which project targets had and hadn’t been met, and then briefly (and I mean briefly) listed the seven future options that were being discussed for the Langholm 2 project. These were:

1. Accept that the project hasn’t worked and abandon driven grouse shooting, but then accept all the negative consequences associated with it (according to Sonja these will be impacts on habitat, species diversity & the local economy).

2. Look for alternative funding, maybe in combination with walked-up shooting, to keep the moorland management and retain the gamekeepers. Sonja thought this was quite unlikely given the significant financial investment required to sustain the moorland management.

3. Look at lethal vs non-lethal control (of raptors) but Sonja pointed out this was highly controversial and unlikely to happen in the current political climate.

4. Look at other mitigating efforts such as “modification of the habitat to discourage voles” (as vole density seems to be the main driver of buzzard hunting over the moor “causing more casualties to grouse”).

5. Look at providing diversionary feeding for other raptors, e.g. buzzards.

6. Make use of intra-guild effects (e.g. the presence of golden eagles can cause ‘spatial avoidance’ in other raptors.

7. Just be patient and wait another five years for red grouse to reach a level of shootable surplus.

I have to say I wasn’t totally convinced by Sonja’s interpretation of what was going on at Langholm, mainly due to the two issues I’ve already mentioned (the high density of red grouse required to trigger driven grouse shooting, and the assumption that raptors are responsible for 90% of the recorded red grouse deaths). My scepticism was further increased when I heard what Mark Oddy (Buccleuch Estates) had to say during the following Q&A session.

[registration_form]

I think the mortality data, estimates and interpretation by Sonja sounds…..sound.

If dealing with relatively fresh carcases it is easy to tell apart raptor vs mammal predation.

The 200/km2 target seems spurious but i wonder whether unlike historical decisions it specifically allows for predation?

I’d have to disagree with you, Tom. Field signs can help determine whether the carcass has been eaten by a raptor or mammal (e.g. plucked quill or cut sheath) but these signs still don’t inform whether the prey was actually KILLED by that species. For example, a red grouse may have succumbed to Cryptosporidiosis or some other disease and been subsequently SCAVENGED by a raptor or mammal. Sonja admitted, during the subsequent Q&A session, that she couldn’t determine whether the red grouse had been killed or just scavenged by raptors.

I’m not suggesting that raptors or mammals don’t kill red grouse – of course they are capable of this and I’ve watched raptors do it. My point is that the claim is being made that raptors are responsible for 90% of red grouse mortality at Langholm, but without the supporting scientific evidence. The claim is being based on assumption, that’s all.

It’s an important distinction to make, especially when the consequential management decisions based on such claims could be so serious.

I’m fairly sure that Simon Lester wrote in his notes that Strongyle worms were by far the biggest killer of Grouse on these moors, was there any way of examining the remains to check what percentage would have died anyway without predation. For example due to heavy investation

Possibly if they are fresh, yes, the carcass can be frozen and checked later too.

Fair points and that is why I said with fresh carcasses, as age of carcase matters.

Now that does not mean disease and age frailties could not contribute to the mortality from predators, it almost certainly does. I would think that more likely than the case of individuals dying of parasitism and then being scavenged.

So I don’t think we disagree, actually?

Another component is that a heavily parasitised or vulnerable young or old bird can still increase a bag, and like predation these birds are over represented in a hunting bag, whereas it cannot if eaten by another predator when live but moribund.

I am not disagreeing with your comment above, that it is difficult to apportion carcase info to cause of death, but it would also be naive to assume that raptors don’t play a part in multiple predation effects.

Remember not one member of staff on either side have ever seen a ‘kill’!! This means how information is gathered is not field work. The best thing that can happen to Langholm is that the community take it over and run it for the benefit of the community which is what the Scottish Government are encouraging especially if they bring back the Golden Eagles which the estate removed. If the estate get it back after the ten years ****************************************** [portion omitted by Mark] One keeper claimed 300 birds of prey a year were killed by the estate on average!!! [Ratcliffe – Galloway and the Borders]

Sonja says…

“4. Look at other mitigating efforts such as “modification of the habitat to discourage voles” (as vole density seems to be the main driver of buzzard hunting over the moor “causing more casualties to grouse”).”

I say…

How can voles be discouraged?

Easily; natural predation by weasels, stoats, foxes, and of course raptors, would keep the vole population at a natural level. But then there is nothing “natural” about the way grouse moors are managed; permanently set Fenn traps all around the moor result in the virtual absence of those mammalian predators.

All leading to the only viable conclusion; Ban driven grouse shooting.

I noticed the comment on voles too, can we now expect to see piles of dead voles next to piles of dead mountain hare’s in the future

Perhaps I’m being naive but my guess is that if you remove all potential buzzard prey apart from an abundance of red grouse, then buzzards will eat more red grouse. Buzzards love a mountain hare don’t they but when what you fancy isn’t on the menu you make do with what’s on offer.

Possibly a little naïve. If the predation of grouse is incidental and the buzzards actually prey on other things, e.g small rodents and rabbits, it may be the case that buzzard density is determined by availability of their main prey. If their main prey is not available in sufficient numbers the buzzard population may fall as territories are abandoned and birds move elsewhere. Thus although a few remaining buzzards may eat more grouse, overall fewer grouse may be eaten. It is of course not a completely predictable relationship so could go either way.

Very interesting – but am I missing something? The bombshell that was dropped during the Q + A appears to have gone off somewhere, but not on this blog.

Miles – yes you have missed something in the first para of the account which says you’ll have to come back for the bombshell at a later date.

Exciting cliff-hanger!

There have been mutterings that the Langholm trial was always going to be put forward as a fail no matter what. The desperation in trying to justify ‘control’ of predators which might affect what is after all a bloated, unhealthy number of grouse is shocking. From the way the data is being presented is legalised killing of raptors going to be the unavoidable ‘solution’? We now have YFTB, and Songbird Survival has been on one of the Scottish estate friendly fb pages saying how important grouse moors are for wildlife – given that native woodland, crested tits, crossbills plus kindred others are in far more trouble than meadow pipits and heather wouldn’t this be strange view from a bona fides conservation outfit? This lunacy has been dragging on for far too long and with the parallel propaganda campaign against the John Muir Trust for actively trying to get red deer numbers down to preserve our pathetic remnants of ancient woodland in Scotland then surely we’ve crossed the point where the the big conservation players need to go on offensive.

On the voles, something I’ve picked up from this blog (I hope correctly) is that there are more voles where there is more grass. The missing actor (villain ?) from all this is of course sheep. The impact of sheep on heather seems to have moved eastwards over time. Back in the late 80s when I was researching the Galloway case study for Birds and Forestry I read the old county avifauna from late 188/early 1900s and was surprised to find that long before forestry came on the scene many moorland birds, including Grouse, were already in decline well before forestry came on the scene. By the time forestry started to have an impact serious grouse shooting was long gone from Galloway and Langholm, well to the east, was by the time of the study clearly on the cusp between heather and grass moorland.

The original Langholm project had as one of it’s main findings the loss of heather to grass due to increased sheep grazing in the preceding 40+ years.

More grass equals more voles and pipits, which are important prey for some raptor thus raptor numbers go up and since raptors also sometimes eat grouse (chicks and adults) then grouse predation goes up….

It does sort of hint that perhaps aiming to get ‘relatively’ high numbers of raptors on the moor alongside ‘relatively’ high numbers of grouse might have been a circle that would never be squared (or at least was very difficult to achieve). The grouse want 90% heather and the raptors need lots of voles and pipits, skylarks and waders that want 50% grass/heather then it could be hard to find a habitat balance that maximises both grouse and raptors….

Did the project always have contradictory aims?

Did people see this? Study of lake sediments shows that the Cumbrian floods of 2005 and 2009 were the worst for 600 years, and two thirds of the worst floods in Cumbria (ever?) have happened in the last 15 years.

https://theconversation.com/under-water-again-when-will-britain-learn-how-to-manage-floods-52166

Have absolutely no desire to get involved in the science or its interpretation here but would like to point out to any readers who may not be aware, that Langholm Moor is an isolated fragment of heather moor in a sea of conifer plantation and sheepwalk. Indeed I have been told locally that the area of sheepwalk, adjoining the Tarras Valley aka Langholm Moor, was at one time the record holder for the most red grouse shot on one day in Scotland. ..My point being that if you were to look for a typical, or even “average” grouse moor to study you would not have picked this one. Which surely makes any study/manipulation here flawed from the start?

very good account Ruth, thank you!

I wonder what Charles Elton would make of the proposals to reduce voles the irruptions of which he linked to destruction of the predators in the borders with the onset of grouse shooting. I think he would be a bit disappointed at the simplistic views of ecology being shown.

This project attracts pubic funding because Langholm is an SPA for hen harriers. Their numbers had declined and had to be recovered. Despite this, only 1 harrier was satellite-tagged last year from a total of 17 fledged young. Possibly there was no funding left after tagging all the young grouse?