After his site was hit with technical problems on the same day my book was reviewed there, Mark kindly offered me the option to post a guest blog on how I came to write the book.

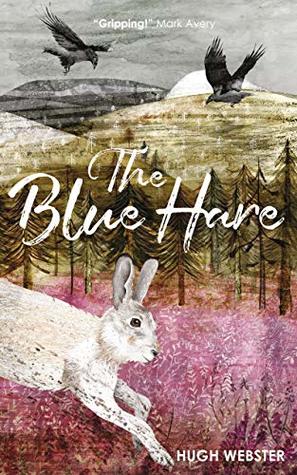

The idea to write The Blue Hare came to me in October 2016 while I was working at a remote research camp in Botswana. It was over forty degrees in the shade and, living under super-heated canvas, it often felt even hotter than that. As my computer’s fan whirred frantically during the sweltering heat of the afternoons, my mind wandered. And then, amidst thirsty elephants and chattering monkeys, the idea to write a fictional book about Scottish mountain hares struck me, quite out of the blue. Go figure.

Actually, it wasn’t entirely out of the blue. Aside from regularly fantasising about cold Northern climes, I had recently read about the brutal hare culls that had been taking place (and continue to take place) on grouse moors in the Cairngorms. Regular readers of Mark’s blog will be familiar with these hare culls (see here, and here) and further details can be found in an excellent report produced by the charity OneKind, which is leading a campaign for a moratorium on the culling. Scientists have recently suggested that these culls might be driving a significant decline in mountain hare numbers, although this suggestion has been vigorously challenged by shooting organisations.

Right from the start then, I knew I wanted The Blue Hare to be a sort of fable that could explore the impacts on wildlife, both positive and negative, of the intensive management commonly practiced on grouse moors. And I wanted it to be a book that both adults and children could enjoy, a bit like that classic of anthropomorphic literature, Watership Down.

Watership Down is sometimes said to have been inspired by Richard Adams’s experiences in WWII, with the rabbit Bigwig’s solitary stand in the tunnel against General Woundwort a tribute to Adams’s friend Paddy Kavanagh. During the desperate final days of the ill-fated Operation Market Garden, Paddy gave his life to allow Adams’s platoon to escape, although Adams was advised by his children that a similarly heroic death for the indomitable Bigwig would be unacceptable, and so the big-hearted old warrior survives his combat. Quite right.

Adams later stated that the “Nazis came into my depiction of the Efrafa warren” but while Watership Down successfully explores the struggle between tyranny and freedom, I wanted to write my own allegorical tale that focused more precisely on environmental conflict, and most specifically on the conflict between gamekeepers and the selection of animals that are unwelcome on Scottish grouse moors.

I was also interested in examining a different sort of choice between tyranny and freedom, presented in the form of the competing attractions of a relatively domesticated existence – as exemplified by the cosseted life of those animals in my story whose existence is favoured by the Keepers’ management regime – versus the hardship and hazards of a liberated life in the wild. I imagined an interesting tension on the moors, where the various animals in this artificial community might feel quite differently about their human “Keepers” with no one point of view uniting them all.

For the haughty curlews and flighty lapwings in my story, the Keepers are rough men who stand ready to defend them against undesirable “vermin” while the older hares assume that the Keepers are acting for the greater good, even though they consider Management’s capricious habits to be beyond understanding. And they all turn a blind eye to the misfortunes of some of the other animals on the moor.

But I wanted to show that such vilification of one group within a community, whether actively or passively endorsed, comes at a cost; not just to the persecuted group, but to the community as a whole. Here I saw a parallel with the poem “First they came” by Martin Niemoller, which skewers the cowardice of the German intellectuals who failed to respond to any of the Nazi purges, emphasising a wider moral message about the risks of turning a blind eye to prejudice and persecution. And of course, the Keepers do come for the hares in the end.

Amongst the residents of High Moor, only Snow is willing to ask questions about the status quo. His curiosity leads him into trouble, narrowly escaping a fire and nearly drowning with his sister in a newly dug drainage ditch. But after he learns that some of High Moor’s residents are being persecuted by the mysterious Keepers and witnesses the destruction of a hen harrier nest, he begins to suspect that the Keepers’ supposedly benevolent management may be more sinister than anyone is prepared to admit. His status as a young leveret seemed appropriate to this role, for so often we grow acquiescent as we grow older, or at least less inclined to rebellion.

In this sense I feel Snow’s journey speaks to a wider truth, that although a regime, any regime, may appear benevolent – may indeed go to great lengths to present itself in a favourable light – it is always important to question the motives of those in power, to be constantly vigilant and to question accepted wisdom, especially when the comfort of some is achieved at the expense of others. I was reminded of this just last month, while witnessing the youth-led climate protests inspired by Greta Thunberg, and I was struck then by how shameful it was that we were leaving it to children to hold our leaders to account. This is still our watch and we have to do better.

For the hares in my story, life on the grouse moor offers the temptation of a life of ease, provided they don’t ask too many questions about how that life is achieved. It is a temptation we might all recognise. But the comfort and convenience of this life ultimately comes at a price. Leap and Snow’s eventual escape into the wild reveals the mountains to be harsh and unsparing, and their quest to find a safe refuge proves in some ways futile, but in the end, they still choose a life in the wilderness far from High Moor because they recognise that out there at least they have a fighting chance. And this remote wilderness offers them a chance to heal, a place to recover from the traumas they have experienced at Man’s hand, and a place they can finally call home.

The Blue Hare is intended to be both an ecological morality tale and a fantastical adventure story, a fable that questions the motives behind human interference in nature and extolls the restorative power of wilderness, a value impossible to quantify but precious beyond measure. If you have read it, I hope you enjoyed it, and below I have outlined a few discussion points that might be of interest to book clubs, school groups or anyone who has read the book.

1) Were you convinced that a wild life offered a better fate for Snow and Leap than their life on High Moor? What are the relative merits of living under Management versus life in the wild?

2) How much blame did you apportion to Tundra and Juniper in their own fate? Should they have been more critical of “Management” and more sympathetic towards those creatures they knew were suffering under the Keepers’ regime? What could they have done differently?

3) Red grouse are classified as wild birds in the UK. In your opinion, how wild are the red grouse on High Moor? How wild are our National Parks?

4) What are the character strengths and weaknesses of Snow and Leap? How do they complement each other?

5) Juniper tells Snow and Leap old stories about bone-crowned Brags and yellow-eyed Faols, while Lochan is terrified of the incomparably fearsome Lugar, even though he has never seen one. What are these animals? How does the book portray a sense of an incomplete ecosystem on High Moor and how does it make a case for rewilding the Highlands?

Hugh Webster is a regular commenter on this blog. He also won the international category of a writing competition on this blog back in 2016 with Are Hunters Conservationists?, and wrote a guest blog, Ethical Hunters?, here in 2017. He has a Ph.D. and has worked as a biology teacher.

[registration_form]

A really interesting post..thank you Hugh…and a wonderful book.I loved following the young hares’ adventures. It should be read widely by adults and children.

A great story to raise questions about our relationship not only with the natural world, but also each other.

Thanks so much for your support Gill! It’s hard work writing and promoting a book, perhaps even for experienced and highly acclaimed authors like yourself, but I have loved every minute of it and if one or two more people become interested in what is happening in our uplands and national parks after reading my book then it will have been more than worth it.