Mary Colwell is an award-winning radio, TV and internet producer winning 14 awards over the last 10 years, including a Sony Gold in 2009. She is also a radio presenter and feature writer for The Tablet.

Mary has written six previous guest blogs here (A Natural History GCSE, 23 November 2012; Shared Planet, 15 January 2015; Curlew Calls, 18 February 2016, Natural History GCSE (2), GCSE in natural history (3) – next step, 8 November 2018, and Natural History GCSE (4), 29 May 2020. Two of her books have been reviewed here too (John Muir, Curlew Moon).

Find her on Twitter as @curlewcalls

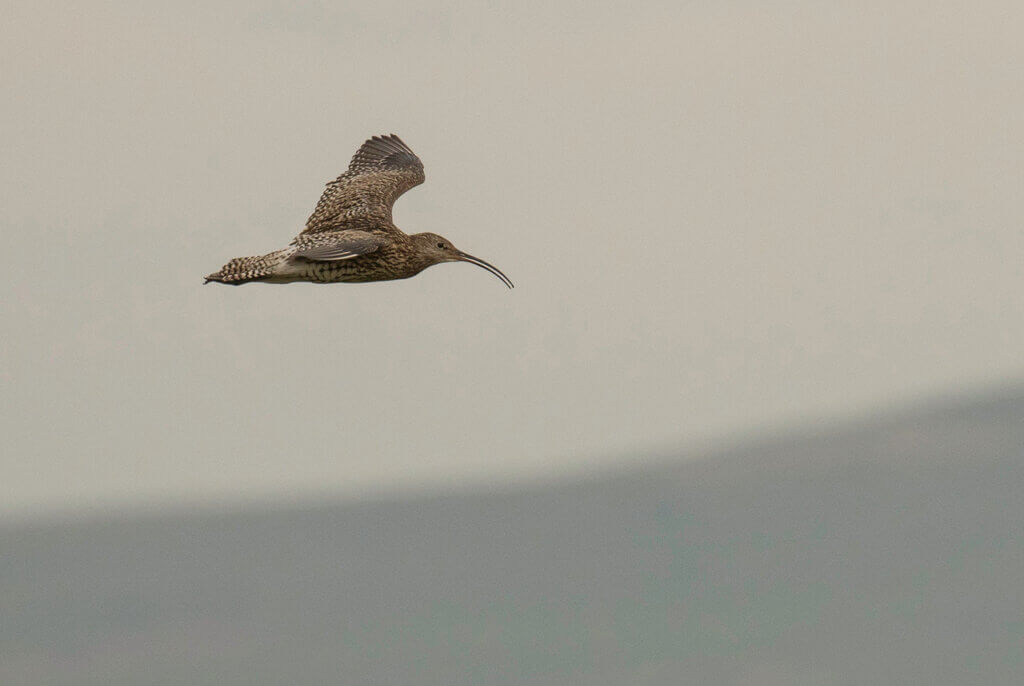

Last weekend, I watched a small flock of curlews on the mudflats on the outskirts of Clevedon. They were restless, flying between the water’s edge and sodden fields, calling their name. Change is coming, wrapped in the warmer wind and longer days – we all feel it. I don’t know where these birds come from, they may be local breeders from the Somerset Levels, or perhaps from northern Europe, but I wish them well in this world where the odds are stacked against their producing any young in the coming months.

Concern for the plight of curlews has been rising over recent years, particularly since the publication of “The Eurasian Curlew – the most pressing bird conservation priority in the UK?” by Daniel Brown et al. in 2015 in British Birds. In 2016, I helped raise public awareness by undertaking a 500-mile walk across Britain and Ireland to find out why they were in trouble, put on curlew conferences and wrote Curlew Moon. Many others have written articles, held events, and curlews are common in posts on social media. HRH The Prince of Wales held two summits, one in a hotel in Dartmoor in 2018 and another in Highgrove in 2020, and a Curlew Summit was held at Downing St in 2019. For a shy bird that stays away from people, it has got a lot of attention. Yet still its magical call and graceful form is disappearing from the landscapes of Britain, because attention alone doesn’t protect it – action on the ground does.

Yesterday, the Curlew Recovery Partnership England (shortened to CRP) was officially launched, with the support of Defra. We have been meeting and planning for a while, as a roundtable of nine organisations that form our Steering Group: RSPB, BTO, GWCT, WWT, Natural England, the Duchy of Cornwall, Bolton Castle Estate, Curlew Action and Curlew Country. We have recently appointed a Chair, me, and a full-time Partnership Manager, Prof Russell Wynn. The Steering Group will not operate alone but reach out to a range of other interested people and organisations, to create a hub with links that spread far and wide. We all have one aim, to turn it around for curlews in England. But this is not just about curlews, because they don’t live in isolation. By protecting curlews, we also safeguard other wildlife that relies on grassy, insect-rich, wildflowery, heathery, muddy places.

The plan is to connect and support the curlew field groups already working, to encourage new projects, to share best practice, to provide an information exchange, to ensure curlews are taken into consideration in the new agricultural world, and to help raise funds. My job is to keep us all focussed on the vision, and Russell has the complex, nitty-gritty role of making it all happen out there in the real world. And it will be complicated and tricky because nothing about conservation in the UK is straightforward to carry out.

The problems faced by curlews are huge – the biggest in conservation. They nest on the ground on farmland and upland moorland, two of our most complex landscapes. The way we manage our uplands is of increasing concern as the whole world grapples with climate change. Windfarms and forestry are mitigation measures that are increasingly deployed across the uplands of Britain, and both impact on curlew breeding areas. Heather moorlands are also the site of grouse shooting estates, with all the emotion and controversy they produce – curlews can thrive on these estates, but increasingly find themselves in the middle of a bitter conflict. In farmland, the intensity of food production, particularly the demand for large quantities of meat and dairy, means frequent silage cutting is a major factor in destroying eggs and chicks, as are high numbers of generalist predators like foxes and crows. In some places, no chicks survive to fledging at all. Just in this one paragraph I have touched on some of the most intractable issues in conservation. No one in the CRP is under any illusion this will be an easy ride.

The CRP’s diverse membership has to be its strength. To make Britain nature-rich once again needs all of us to agree on a vision and to work towards it. We may have different ideas on how to get there, but the goal is the same – to make the world better for curlews and the associated landscapes and wildlife that they live with. All of the organisations involved have to cut down on the rancour, build on success, be open about disagreements and commit to resolving them with mutual respect. Only the years ahead will reveal if we manage to forge a new path, one that diverges away from the mire that bogs us down and stops progress, but I am optimistic we can. British wildlife deserves better, that we make this work.

Author and naturalist, Jonathan Tulloch, wrote recently that “I can never hear a curlew without feeling forgiven.” We are all implicated in the damage being done to nature, and it is heartening to see many new initiatives developing to repair the broken natural world in the UK. Wildlife is immensely forgiving if we allow it the space it needs. I hope the curlew will begin to sing its soul-touching song in increasing numbers over England, and that it will be the sound of success that spurs us all on to greater things.

It is a fine thing to do this but is grouse shooting is there for Curlews or self preservation we know from RSPB Doves Stone that Curlew numbers can be increased by habitat management without predator control or mass intensive burning. Yes I know I’m cynical but years interested in our uplands teaches that.

I’ll say it again…

What if Curlews ate Red Grouse?

Coop – what sport they’d have!

But the focus is not solely on the uplands, I believe. All thoseriver valleys used to have Curlews – far from any Red Grouse.

Indeed, Mark.

I applaud Mary on her excellent efforts, but the question still stands. Let’s put it another way…

What if corvids (Choughs aside, of course) were as threatened as Curlews? Would shooting organisations be queueing up to jump on their conservation bandwagon in similar fashion?

I think we all know the answer to that…

Most of the pictures they show of curlews and other waders on ‘grouse moors’ seem to have a dearth of heather and grouse, but lots of sheep and grass in the background instead.

Funny you should say that, I’ve heard a convincing eyewitness account of curlews swallowing grouse chicks whole. And if waders were believed to harbour a disease inimical to raising large numbers of grouse would curlew be culled like mountain hares used to be on the grounds it’s because of grouse shooting there are so many of them in the first place so it’s OK to kill a ‘few’, or would they just ‘disappear’ like hen harriers do?

We know all too well from another RSPB reserve, Lake Vyrnwy, that habitat management by itself is NOT sufficient to achieve an increase in the curlew population. See Fisher G. & Walker M. (2015) Habitat restoration for curlew Numenius arquata at the Lake Vyrnwy reserve, Wales. Conservation Evidence, 12, 48-52. At the time of that paper there were 3 pairs; at the last count, there was one.

Mary is sensible and open-minded enough to know that in certain areas curlew recovery will indeed depend on prescriptions derived from successful grouse moor management; and that includes predator control that is sufficiently intensive to be effective.

Yeah, a good dose of burning, draining, and track construction will do them the power of good! And, in hard times, they’ll be able to supplement their diet with some tasty lead shot.

It may indeed help a species in trouble if you kill off the other species that eat it, but it’s an emergency measure at best and one that can mask the underlying problem, and therefore a convenient distraction for some. If it succeeds it doesn’t mean the predators are necessarily the problem just that killing them compensates for what really is. What are the real problems and therefore the real solutions? Could the issue with foxes be the vast input of protein into the countryside in the form of pheasant and red legged partridge at a time when natural protein availability should be declining?

If there’s some sort of imbalance with corvid numbers then I would far better trust that can be restored by the return of the goshawk than by a gamekeeper. How is that supposed to work anyway, does the keeper get up in the morning listen to the birdsong and go ‘yep we need to get rid of 12 magpies, 7 crows and 3 jays’ or do they just kill as many as possible? I’ll go with goshawk and their highly evolved interaction with their prey species thank you very much. And if you want to see somebody not listening to what’s awkward you should try getting a gamekeeper to admit pine martens have been good for red squirrels.

But Les, the curlew is facing an emergency right now; and in some cases the level of predation pressure, and its impact on productivity, is indeed one of the most significant causes. The science is clear – and has been for years. For example, look at the work that Murray Grant did in Northern Ireland in the 1990s: https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2664.1999.00379.x Nothing to do with pheasants and partridges there. Nor at Lake Vyrnwy, incidentally. I would also commend the results of the 10 year-long Upland Predation Experiment at Otterburn: https://www.gwct.org.uk/media/249256/waders_on_the_fringev2.pdf

Ladywell makes a pertinent point but not taken seriously here (re comments) as usual.

Mary asks us to understand that land use, and management, including grouse moors, is crucial to saving the curlew. She asks us all to work together, not all moors are the same. I know that Mark says that thus has been ineffectual, but there are good apples too. Like it or not grouse moors are important breeding grounds for waders and fox control is key to successful breeding. Fox numbers in UK are un- naturally high because of man, maybe wolves and lynx would reduce numbers, but they are currently missing from the food chain. The RSPB and Wildlife Trusts have to electric fence foxes out of wet grassland reserves to get many wader young off.

I am not supporting driven grouse moors but we should recognise their importance for waders. The comments on this blog often come across as an echo chamber for an ideal world where if we got rid of grouse moors all would be great. Well, without land management (eg. grazing, fox control) we will loose lots of our curlews and more. We would gain more hen harriers, but that should not be the be all and end all.

Currently, in the Lothians and Borders land some land owners and farmers are making bird surveyors less welcome and stopping vehicular access as the anti shooting retoric and publicity rises. Is this a productive way forwards?

The majority of readers of this blog are fully aware that targeted, evidence-based predator control, used as a last resort, is a useful tool, of undeniable efficacy.

However, the readers are also aware that there is a vast difference between the above, and the wholesale, prejudice-driven campaign of extermination that occurs on intensively “managed” shooting estates.

Populations of Curlews (and other waders) remained extant for millennia before the invention of grouse moors and gamekeeping; as part of functioning ecosytems, including a full suite of both mammalian and avian predators, and are in no way dependent on this land use.

It’s all too apparent that shooting interests’ “concern” for wader populations is simply an excuse to continue with their damaging activities, with the sole motive of maximising the “shootable surplus” of quarry species and the profits therein.

I repeat: What if Curlews ate Red Grouse?

There was grit, energy and determination in your piece Mary that makes me feel a lot more optimistic for the curlew. I believe that they have this and other waders at RSPB Insh Marshes and regularly have to maintain the habitat for them by clearing scrub. I’m sure I’ve heard that this reserve could very well be the best place in Britain to have beaver. Depending on how well they control scrub having them back could be good news for curlew too. Unfortunately in Scotland at the moment beavers cannot be released or translocated outside of their existing range they have to expand naturally so it will be a long time before they get their own.

A manager for the Cairngorms National Park stated at a conference that any beavers just turning up at Insh Marshes will be treated as an illegal introduction and then removed, a threat that was carried out Beauly where two of the live trapped beaver subsequently died. How the beaver interacts with curlew might produce very pleasant and productive results. So can I humbly suggest the CRP looks at lobbying to get ‘problem’ beavers translocated to the Insh Marshes, I’m sure the RSPB would be sympathetic, to gauge the implications for beaver assisted curlew conservation?

Yes, I’m sure beavers could certainly help all wildlife that likes boggy meadows and flood plains.

Shame we are currently building houses and rail lines over lots of this habitat.

I passed lots of new build sites and various HS2 sites yesterday and the destruction going on out there is beyond comprehension.

Surely we need a vision to restore the floodplains of our great rivers like the Thames and Severn ? Whether for Curlews or flood prevention the case is overwhelming. Surely it’s the opportunity for Environment Agency Chair Sir James Bevan’s fine words about climate change to be put into immediate and rapid action ? And with the Government saying agriculture money will go to public benefit surely the route is there to supporting floodplain farmers in multi-purpose land management rather than solely maximising crop output ?

And in the uplands, we need to move new woodlands down the hill – there’s an assumption that new planting, moorland and Curlews must clash but the lower, mineral soils, as opposed to higher peatland, promoted in the recent RSPB report are – and always have been – a far better place to produce timber than the the high peatland Curlew moors. Trees were forced there by the absolute – and damaging – priority given to maximising agricultural production – which, incidentally, has also contributed hugely (probably more than forestry) to the decline of Curlew through the ‘improvement’ of ever more marginal land.