David Parkin was born in Sheffield and raised on Tyneside. He started birding at age 12 and decided to study Zoology after hearing talks by Denis Summers-Smith and John Coulson as a teenager. After a short spell at Edinburgh he moved to Nottingham in 1971, remaining there for the rest of his career (choose your rut with care – you may be in it a long time!). In collaboration with Jon Wetton, he developed techniques for DNA fingerprinting raptors and helped the RSPB with some of their first ‘molecular prosecutions’. He is also one of the ‘sodden 570’.

Memories of Fair Isle – David T Parkin

My first visit to Fair Isle was in September 1961. A talk to the local natural history society by Ken Williamson fired up my interest in what sounded a magical place heaving with rarities. So, next autumn, a bus from my home in Gateshead to Newcastle, a train to Aberdeen, overnight on the MV St Clair to Lerwick, a bus to Grutness and finally the Good Shepherd across to the island.

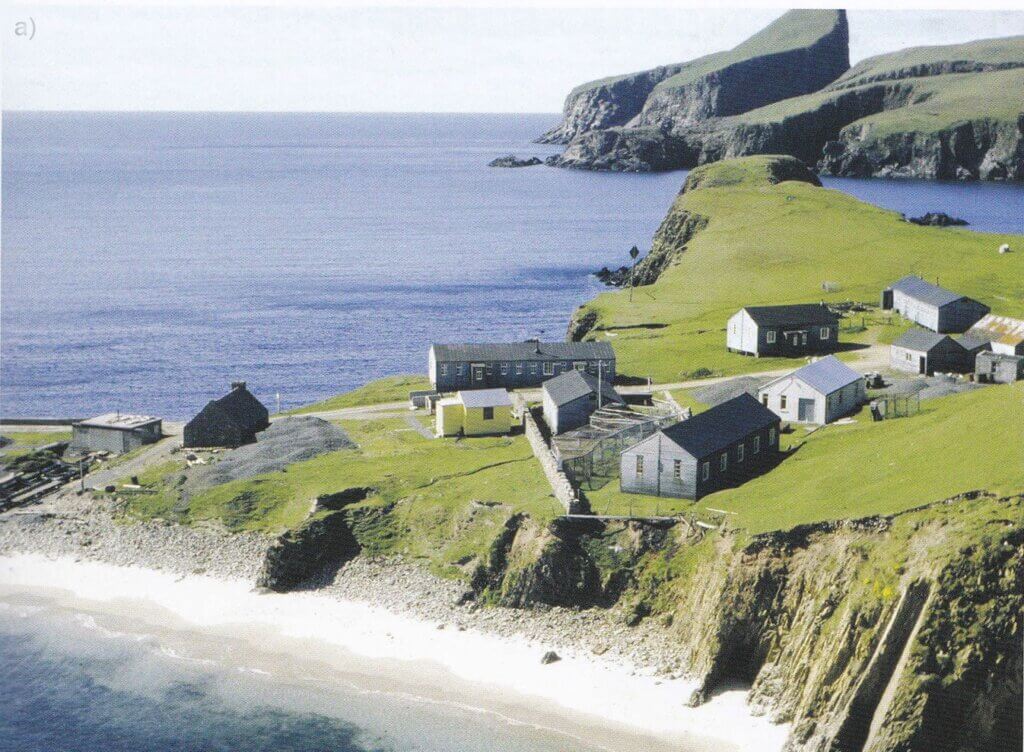

I was met by Peter Davis and Gordon Barnes and shown my accommodation. This was little more than a tiny room in one of a series of sheds. Ex naval huts from the Second World War, they were cold, damp and draughty. Hot water was provided in each hut by a coke boiler. These were small and inefficient, needing to be stoked through the night to keep alight until morning. Each resident took turn to sleep with an alarm clock set for 3 a.m. Get up, sleep-walk down the corridor, load on a couple of shovels of coke and go back to bed. Pass the clock on to whoever was next on the rota. On the subject of water, a collection of little creatures usually emerged from the tap and swam round in the basin. Also, we were warned about liver-fluke in the sheep at the south end of the island– though I was never certain whether this was true or just some joke at the expense of naïve young visitors. After an introductory walk and talk by Gordon Barnes, and a meet-up with other guests, it was getting dark. Here I was introduced to the ‘log call’ over a mug of hot chocolate and a slice of ‘peat’.

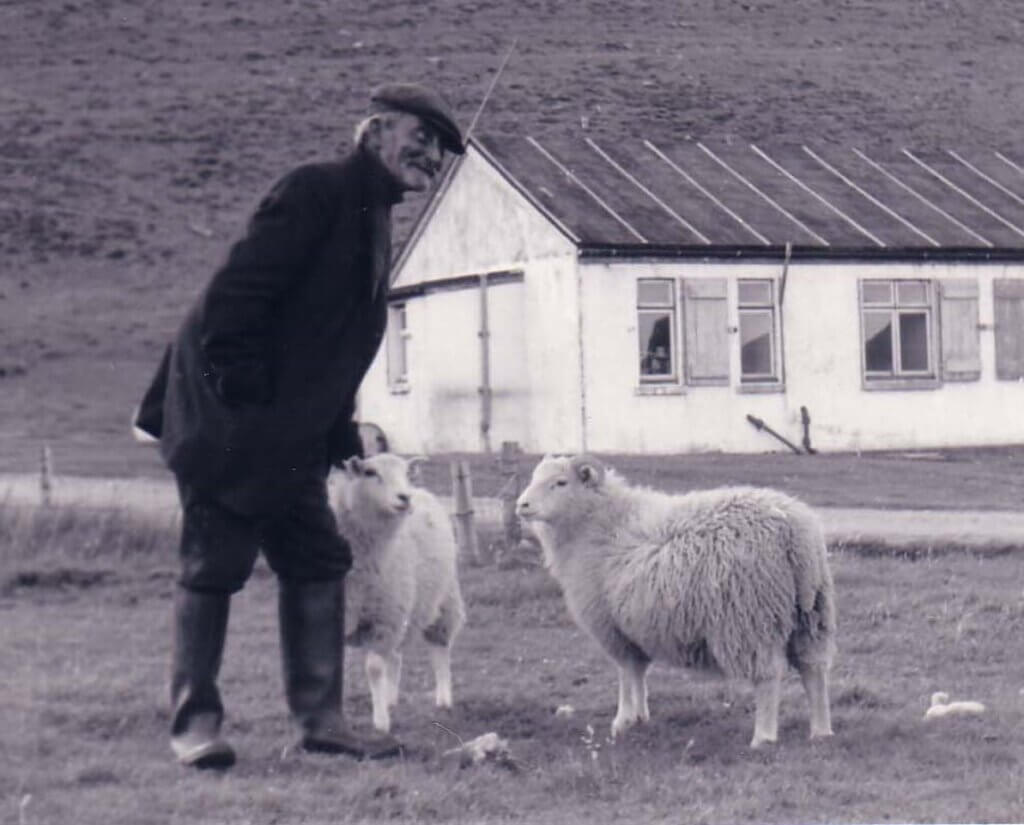

Catering has always been central to any visit to the island. In the early days, perhaps the best word is ‘sustaining’. The Observatory had its own flock of sheep, so lamb and/or mutton was served in various forms four or five times a week. There was still some serious fishing by the crofters, so fish was regular. And, if all else failed, the Assistant Wardens went out with a gun and we had rabbit. On one memorable day in vile weather, under Roy Dennis’ stewardship, a Pink-footed Goose flew into the North Light and we got, not only an Icelandic ringing recovery, but also a roast goose dinner!

On my first morning, we were up at dawn and off on my first trap-round: in those days, guests were allowed to drive the traps and extract birds. It was all very magical and the legendary George Stout (Fieldy) turned up regularly to chat. Every time I visit the island, I pay my respects in the graveyard. During this first visit, lifers came at me from all directions: one day, I got six including Rosy Starling, Rosefinch, Little Bunting and Citrine Wagtail. Tyneside suddenly seemed very tame and I determined to return the following year.

So, back again, with Barrie Spence as Assistant Warden since Gordon had taken over the croft at Setter. Part of the routine was for visitors to do the washing-up after meals. This was organised on a rota, but there was one serious down-side. To help guests (and staff) get round the island, the observatory had a set of elderly bicycles. Unfortunately, there were fewer cycles than residents, so whoever was on washing-up duty left the observatory last and had to walk. One day, my partner at the sink (let’s call him ‘Bill’ – because that’s his name!) decided that we would hide two bikes behind one of the buildings so that we got to ride down the island. Great fun! Alas, as we cycled south, we met Peter Davis returning from taking his son to school and incandescent with rage. One of the appropriated cycles was his and he had to carry the boy across the island. As punishment, we were put on washing-up for the rest of our stay. Next morning, Bill and I set off long after the rest had departed. They had all hastened down the island passing the Double Dyke trap without stopping. As we approached, we found a wagtail – Citrine! We tossed, I lost and ran down the island to tell everyone and caught up with them over a mile away at the south end of the island by The Haa. They all leaped on their bikes and set off – leaving me to run all the way back to the DD. By the time they arrived, the bird had flown into the trap and Bill presented it to Peter in a bag. Peter must have been seriously annoyed: despite this being only the fourth British record, neither of us was credited with this record in the BB Rarities Report!

On the subject of sheep, the islanders kept a small flock on the top of Sheep Rock. Each year, a series of visits was made to check their health and thin out the numbers. This was a potentially hazardous task as access was by hauling yourself up a chain. One evening, we were reading a piece in the old hand-written logs written by Maury Meiklejohn about his joining this exercise to see what birds were up there. Apparently, it was pouring rain from a swirling mist and his only bird was a single Meadow Pipit. He inaugurated the ‘Meiklejohn Prize’ for the fewest birds seen on the island in a day. Bill (the same one as in the cycling escapade) decided to break the record and see nothing! Peter Davis insisted that he had to go out of the observatory, and not simply sit in the common room all day. So, we blindfolded him and led him by the hand round Buness. He almost saw a Redstart, but, just in time, I managed to slam the privy door in his face. Overnight, the wind turned easterly and we were able to get back to the serious business of birding.

Back in the 1960s, there was no TV in the observatory, and were reliant on radio for news – especially the weather. Fond memories of huddling round the radio for the shipping forecast at dawn, midday and (especially) early evening, eagerly listening for easterlies in Viking, Forties and German Bight.

Then, in 1968, things changed with the construction of a new Observatory. Much more civilized! Warm bedrooms. Hot showers. Drying Room. Comfortable Common Room. And with regular flights by Loganair, no need to brave the Atlantic on the latest incarnation of the Good Shepherd. A visit in October 1979 yielded two memories. First, an Isabelline Shrike lurking among the oil drums at Duttfield in a howling SE gale. Iain Robertson, warden at the time, turned up to see it just as it lifted off and was carried away on the gale. Next stop? Foula? Iceland? Who knows. We certainly never saw it again. A couple of days later, Clare (then aged 8) and I drove the Gulley and caught a female Sparrowhawk. No bag big enough, so Clare carried it back in dad’s sock. Poo! Gosh! Next day, same place and another Sparrowhawk. “If you catch one tomorrow, Clare, you can ring it” said Iain. Look of horror on his face as she walked into the observatory next day again clutching one of dad’s socks. The Assistant Wardens reminded Iain that she could be emotionally scarred for life if he went back on his word. I doubt any Sparrowhawk has ever been handled with such care: Observatory staff holding the bird still; Iain holding Clare’s hand around the pliers. We never told the Ringing Office!

This was also an era before mobile phones. If a rarity was found, one staff member drove slowly round the island waving a red flag. If you saw it, you ran like hell to the nearest road to find out who had seen what and where.

A few years later and back again. This time with (the late) Steve Henson. On one magical day we found a Pechora Pipit and a ‘Siberian’ Stonechat among a host of scarce migrants. Best of all was a female-type bunting which, at the time, no one saw well enough to determine whether Red- or Black-headed. Opinions were divided: one observer who had been watching Black-headeds in Turkey a few weeks previously was adamant that it was this one. Eventually, it was trapped by Pete Ewins and Dave Okill and was clearly Red-headed. Said observer (name redacted) commented that he had believed this all along! Dismissed as an escape and released (without even a photo!), but turning up in company with Pechora Pipits, a Lanceolated Warbler and a Siberian Stonechat it has to be the strongest candidate yet for a wild bird? It’s on my list! Incidentally, Mrs P came for a week at this time and was seriously unimpressed with Fair Isle – cold, wet and her bottle of gin only lasted four days!

Over the years, Fair Isle gained a serious reputation as a base for scientific research. As an evolutionary geneticist, for me the most significant was the study of Arctic Skuas by Peter O’Donald and John Davis from Cambridge University. Careful monitoring of pair formation and breeding success showed differences between the colour forms that went part way to explaining why the polymorphism persists. Unfortunately, the decrease in the population meant that continued study was not viable. Talking of skuas reminds me that Fair Isle is one of four locations where rigorous long-term seabird monitoring has been undertaken. The same stretches of cliff are censused every year, recording number of pairs, hatching and fledging success. These data are used to generate national indices of abundance, some of which are very troubling. As is now generally well-established, Kittiwakes have declined alarmingly in recent years, as have several other species. Climate change resulting in warmer seas and changing fish stocks have been proposed as a driver of these declines.

Back to the observatory itself. Communications with the mainland had improved greatly; no longer the necessity for the stomach-churning Good Shepherd. And in 2011 a new building was completed. Thanks must go to Deryk Shaw who was warden at the time and who, with his wife Hollie, facilitated operations. The new building was formally opened by Roy Dennis in the presence of an array of Fair Isle friends. This was a spectacular building, and even the birds put on a show – David Jardine found a Black-headed Bunting. Ian Newton, Andy Clements and I all ‘needed’ BHB for our British list. We scoured the island to no avail (it turned up again just after we left!). I have said several times that when the Director of the BTO and Britain’s senior ornithologist spend most of a day looking for a new bird, British ornithology is in safe hands.

The backbone of bird recording is the daily round. Through the migration periods, the Warden and his two assistants walk standard routes around the island. All birds are recorded with estimates of abundance, supplemented by observations from the guests. These are now input directly into a computer database at the daily log-call. However, for over half a century, records were made on paper and stored in the observatory. Thanks to the efforts of Roger Riddington, these data had been digitised for secure storage. Imagine the tragedy of losing over seventy years of daily counts? These digital data are already being ‘mined’ and Will Miles has produced important reviews of the changes in attendance patterns since the observatory’s founding.

As most birders know, this wonderful building was destroyed by fire in March 2019. Everything was lost, but thanks to a spectacular crowd-funding-effort, David & Susannah Parnaby and their family were able to replace many of their lost possessions. Although, of course, items of a personal or sentimental nature are irreplaceable.

The Trustees have planned a new building and this should be open by spring of 2022. The Phoenix has been seen over Fair Isle! Despite support from the insurance companies, there is inevitably a shortfall in funding. So, whether your background is in science or birding, or just as someone who loves islands and their uniqueness, now is the time to put your hand into your pocket! Details of how you can donate (via PayPal or by BACS) are at http://www.fairislebirdobs.co.uk/donations.html. By donating to the rebuild appeal, you are contributing to the provision of significantly enhanced research facilities for world-class ornithological and additional marine biological work.

What a wonderful account of a magical place. I’ve only been to Fair Isle once – staying for several weeks in September 1975 – but this conjured up lots of memories. Plus, the recollection of a particularly stormy trip on the Good Shepherd, when we had to stay in the cabin and one of the crew was repeatedly sick. Thankfully, neither of us two passengers was. Needless to say, the birds were spectacular.

Fair Isle is a very special place, any one who has visited it quickly succumbs to the spell of the place, the people and the “high anticipation” birding where else will you have such a good chance of seeing and may be finding a major rarity. I’ve only been visiting in the last 10 years, one of the best suggestions friend Ian has ever had, quite why either of us waited so long is certainly beyond my comprehension. David conjures the magic of the place very well in his blog, good days there are almost beyond imagining, even an average Fair Isle day during migration is pretty good. The observatory loss was a tragedy not just to the birding but to all the Fair Isle community it is such a vital and important part of island life and its economy so if you can please donate to the new observatory fund. When its open visit and like us you will wonder why you never came before!